FOI 24/25-0223

Document 10

OFFICIAL

Research – Length of High Intensity Intervention for ABI, SCI and

Amputees

In order to develop business rules for the amount of funding to include as a

capacity building support within the Participant Budget Model, the following

information will assist us:

• For the following disability groups: Acquired Brain injury, including

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI), stroke, brain tumour AND spinal injury AND

amputations as separate groups.

• What is considered best practice in terms of:

a) The length of time for which high intensity therapy supports are

considered effective after onset?

b) How long does high intensity rehab continue post spinal cord injury or

amputation?

There is a period of time (previously termed ‘spontaneous recovery’) when it is

Brief

considered that the brain is more amenable to learning new information/skills

after a brain injury.

In the past it was accepted that this period of relatively rapid learning would

then be followed by a plateau, when limited new learning was possible.

c) What is the current thinking regarding: i) whether there is a plateau;

and ii) when this point is reached for brain injuries?

We are considering the possibility of 5 years as an appropriate time to cease

high intensity rehabilitation, and “switch” to maintenance/monitoring supports

for brain injuries; and 2 years for spinal cord injuries or amputations.

d) Is there any research evidence for this?

e) Does this align with research and length of time for improvement post

acquired injury?

Date

09/07/2021

Requester(s)

Jane Ss47F - personal privacy

Jeán Bs47F - personal privacy

Researcher

Jane Ss47F - personal privacy

Cleared

N/A

Please note:

The research and literature reviews col ated by our TAB Research Team are not to be shared external to the Branch. These

are for internal TAB use only and are intended to assist our advisors with their reasonable and necessary decision-making.

Delegates have access to a wide variety of comprehensive guidance material. If Delegates require further information on

access or planning matters they are to call the TAPS line for advice.

The Research Team are unable to ensure that the information listed below provides an accurate & up-to-date snapshot of

these matters.

OFFICIAL

Research – Length of High Intensity Intervention for ABI, SCI and Amputees

Page

1 of

13

Page 1 of 13

FOI 24/25-0223

Document 10

OFFICIAL

The contents of this document are OFFICIAL

1 Contents

2 Summary ......................................................................................................................................... 2

3 Traumatic Brain Injury .................................................................................................................... 3

3.1

Length of time high therapy supports are effective ............................................................... 3

3.2

Recovery Plateau .................................................................................................................... 3

3.3

Impairment two years after brain injury ................................................................................ 4

4 Spinal Cord Injury ............................................................................................................................ 4

4.1

Length of time high therapy supports are effective ............................................................... 4

4.2

Recovery Plateau .................................................................................................................... 5

5 Amputation ..................................................................................................................................... 6

5.1

Length of time high therapy supports are effective ............................................................... 6

5.2

Recovery Plateau .................................................................................................................... 6

6 References .................................................................................................................................... 11

2 Summary

• Because randomised control ed trials (RCTs) often have limited funding,

interventions are rarely delivered past the 12 month mark. Because of this, we can

only make assumptions about the effectiveness of rehabilitation for TBI past these

timeframes.

o The consensus is, the earlier intervention occurs the better.

o The timeline and level of recovery differs between patients. Therefore, the

length of rehabilitation should be guided by the patient’s needs.

• Most commonly, the plateau for TBI improvement is around the 2 year mark.

However, various studies have put the range anywhere from 6 months to 2 years.

• Most spinal cord injury (SCI) cases reach a plateau by 9 months after injury.

However, additional recovery may occur up to 12–18 months.

• There is no agreement on duration and intensity of intervention in the acute and

post-acute phases of SCI

o Most studies implement intervention over 6 to 12 weeks.

o Rehabilitation should be implemented when patients are medical y stable

and can tolerate the required intensity.

OFFICIAL

Research – Length of High Intensity Intervention for ABI, SCI and Amputees

Page

2 of

13

Page 2 of 13

FOI 24/25-0223

Document 10

OFFICIAL

• Unable to determine a timeframe for plateau in relation to amputees, however, the

time needed to progress through rehabilitation phases is consistently reported to be

between 12 and 18 months.

3 Traumatic Brain Injury

3.1

Length of time high therapy supports are effective

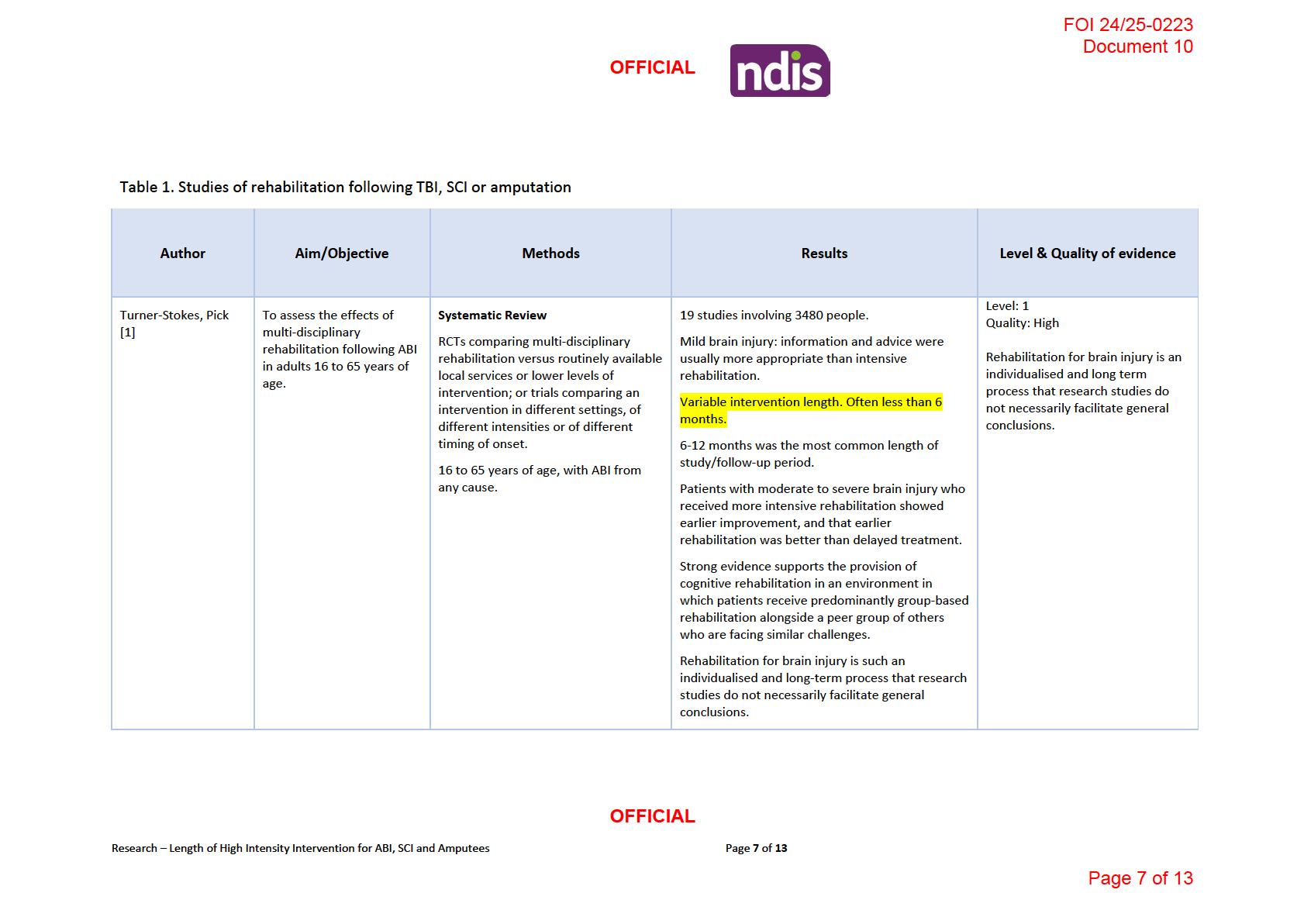

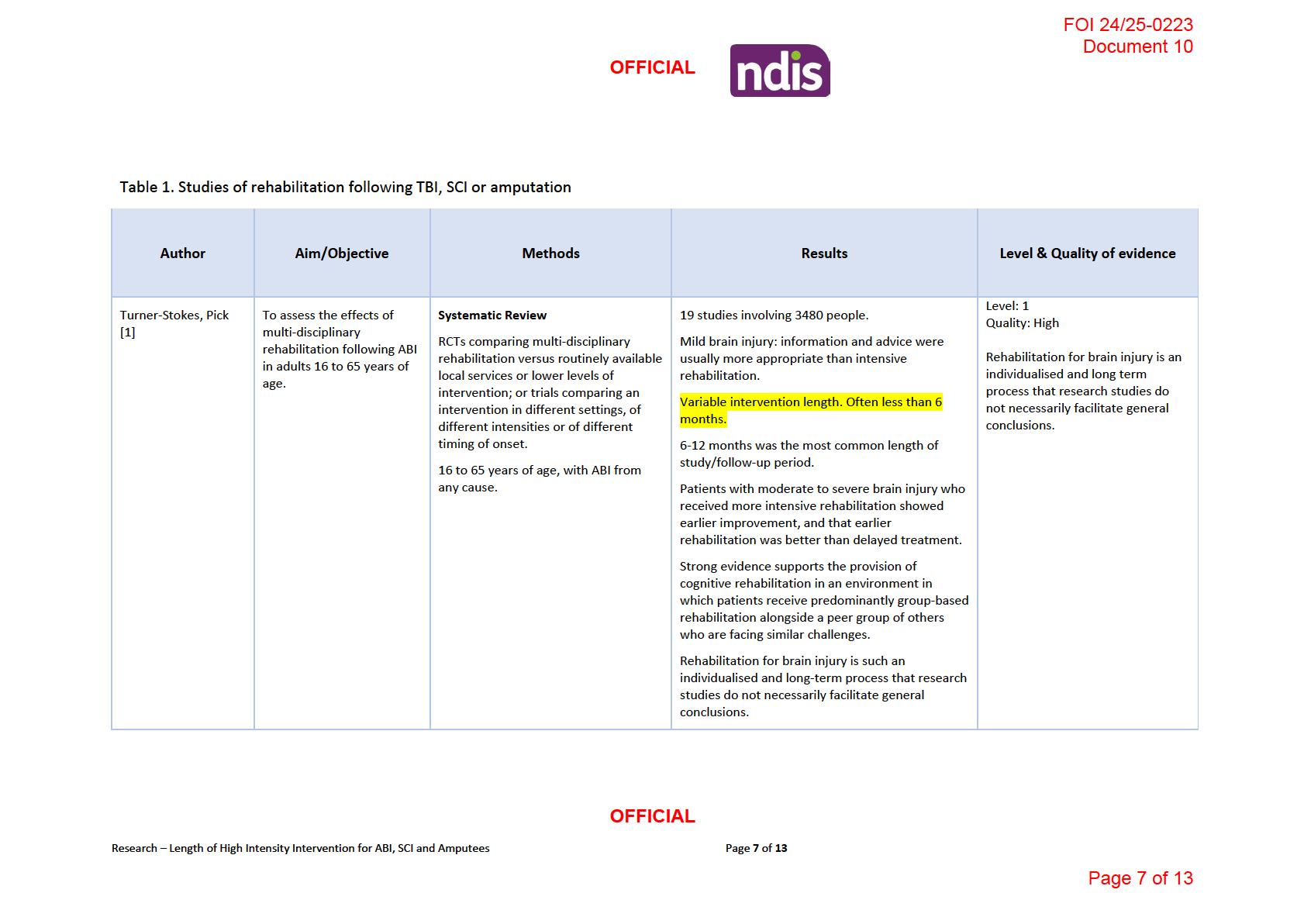

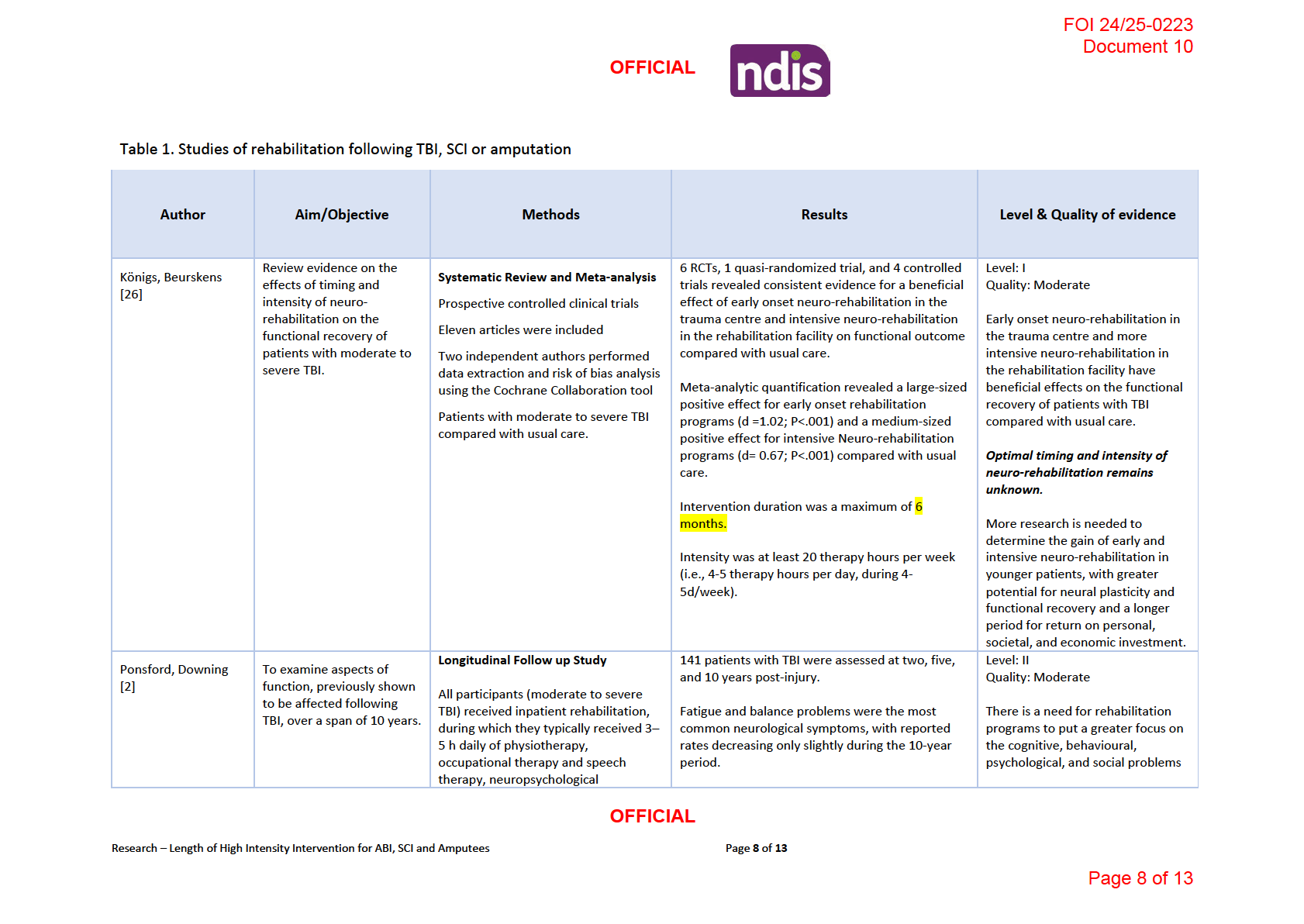

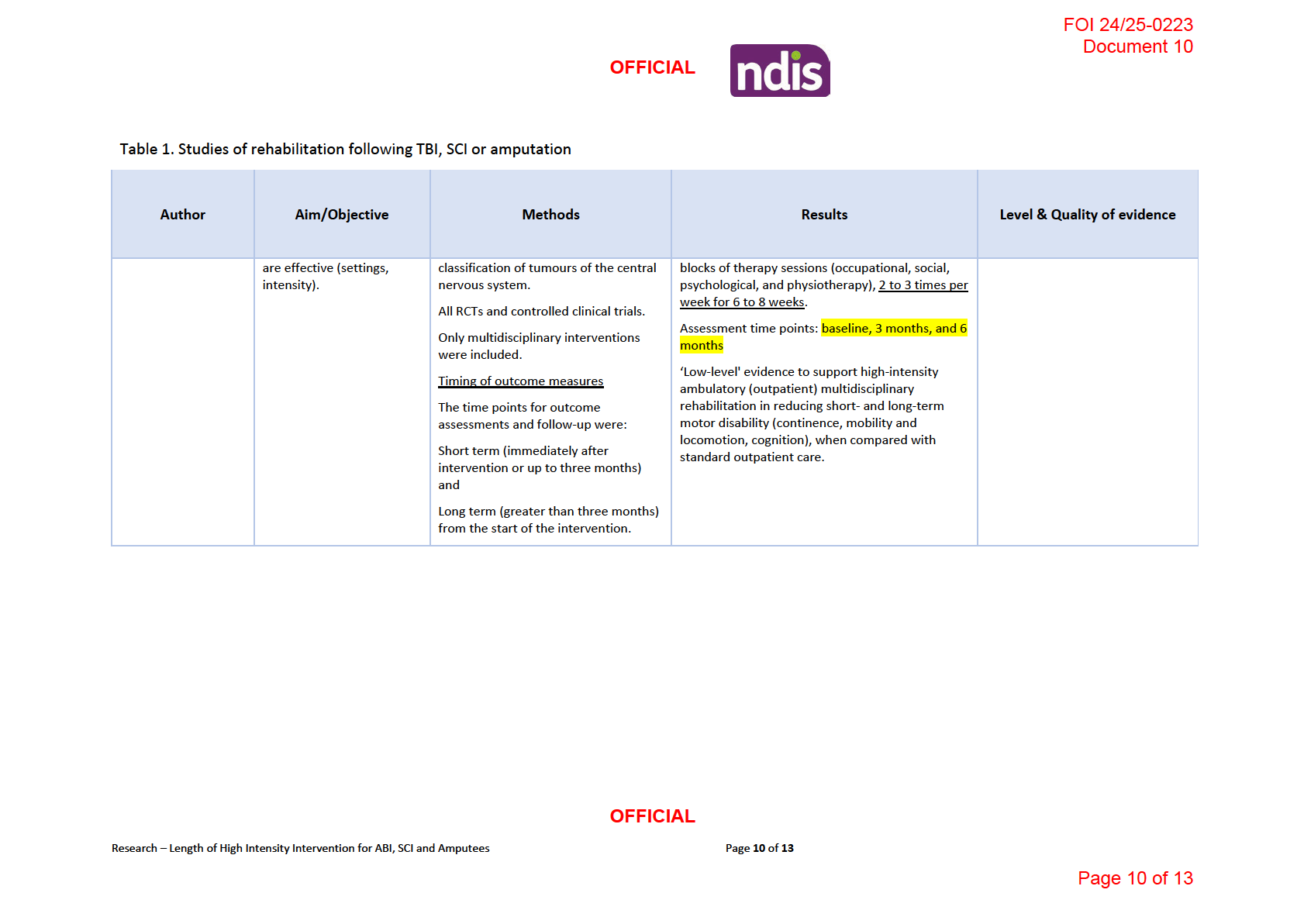

Systematic reviews investigating intensive multidisciplinary rehabilitation (in the post-acute

stage) on average implement the intervention for less than 6 months and fol ow up study

participants anywhere between 6-24 months. Refer to Table 1 for more details.

The length of time over which rehabilitation may have its effects (always many months and

usually several years) is usually longer than any funded research project [1].

Benefits of neurological rehabilitation typically accrue over several years, rather than over

weeks or months. RCTs are typical y conducted over a much shorter time. Definitive RCTs in

this area should be funded to include fol ow-up over three to five years but this is rarely

possible under existing funding programmes. Furthermore, studies with long fol ow up

periods tend to have high dropout rates, leading to less meaningful results due to smal er

sample [2].

For patients engaged in rehabilitation, intervention should be offered as intensively as

possible and should begin as early as possible, although the balance between intensity and

cost-effectiveness has yet to be determined [2].

3.2

Recovery Plateau

Review of the existing TBI cognitive recovery literature indicates that recovery does indeed

occur after TBI and that recovery curves are likely to be differentially sensitive to both

recovery domain and time [3]. Most studies have employed global measures of functional

outcome including: vocational status, Glasgow Outcome Scale, the Disability Rating Scale,

the Community Integration Questionnaire, and the Functional Independence Measure [3].

Recovery is detectable, asymptotic (when more than 3 points are measured), and

commonplace after TBI. Studies remain ambiguous about the pace of change over time and

the point at which a plateau in recovery is achieved [3]. Expressly, some studies observe

continued recovery as late as

2 years post injury [4-6] while others note no further recovery

after

1 year [3, 7], while still others indicate full recovery as early as

6 months post injury [8,

9]. The discrepancies between findings may be attributable to the disparity across studies

with regard to both study design and outcome measures [10].

Longer term longitudinal studies investigating post injury outcomes have shown mixed

results. Newcombe [11] found that veterans who had had a head injury in the showed no

OFFICIAL

Research – Length of High Intensity Intervention for ABI, SCI and Amputees

Page

3 of

13

Page 3 of 13

FOI 24/25-0223

Document 10

OFFICIAL

evidence of deterioration many years after injury. This might have been due to the expert

and systematic care they received very soon after the injury. But other researchers found

that a proportion of patients deteriorated when assessed 10-20 years later. In contrast,

Dams-O'Connor, Ketchum [12] found a decline in functioning and decreased independence

5 years post injury. Similar results were also found by Millar, Nicoll [13] and Olver, Ponsford

[14], however, a percentage of patients did make improvements. Furthermore, Ponsford,

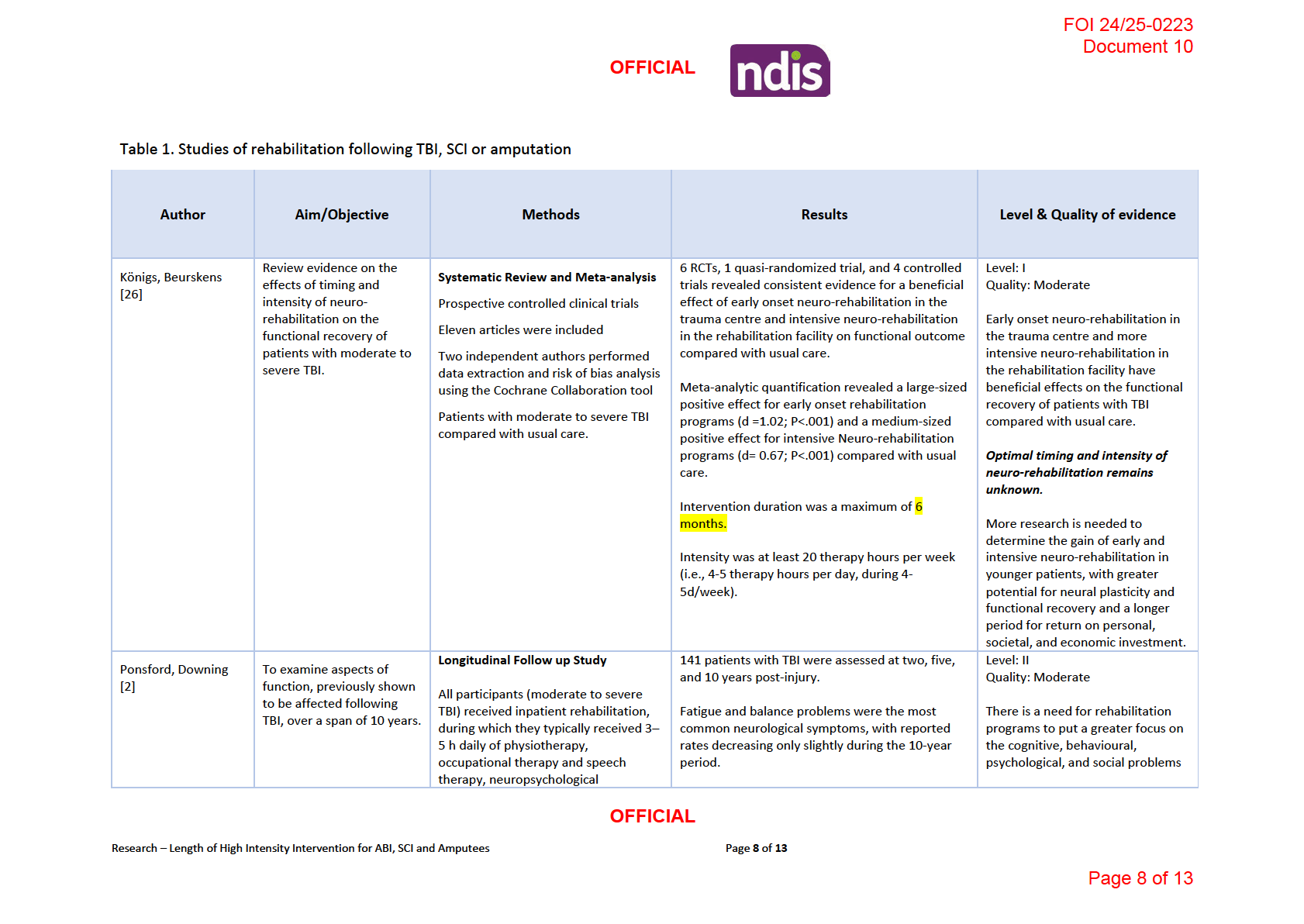

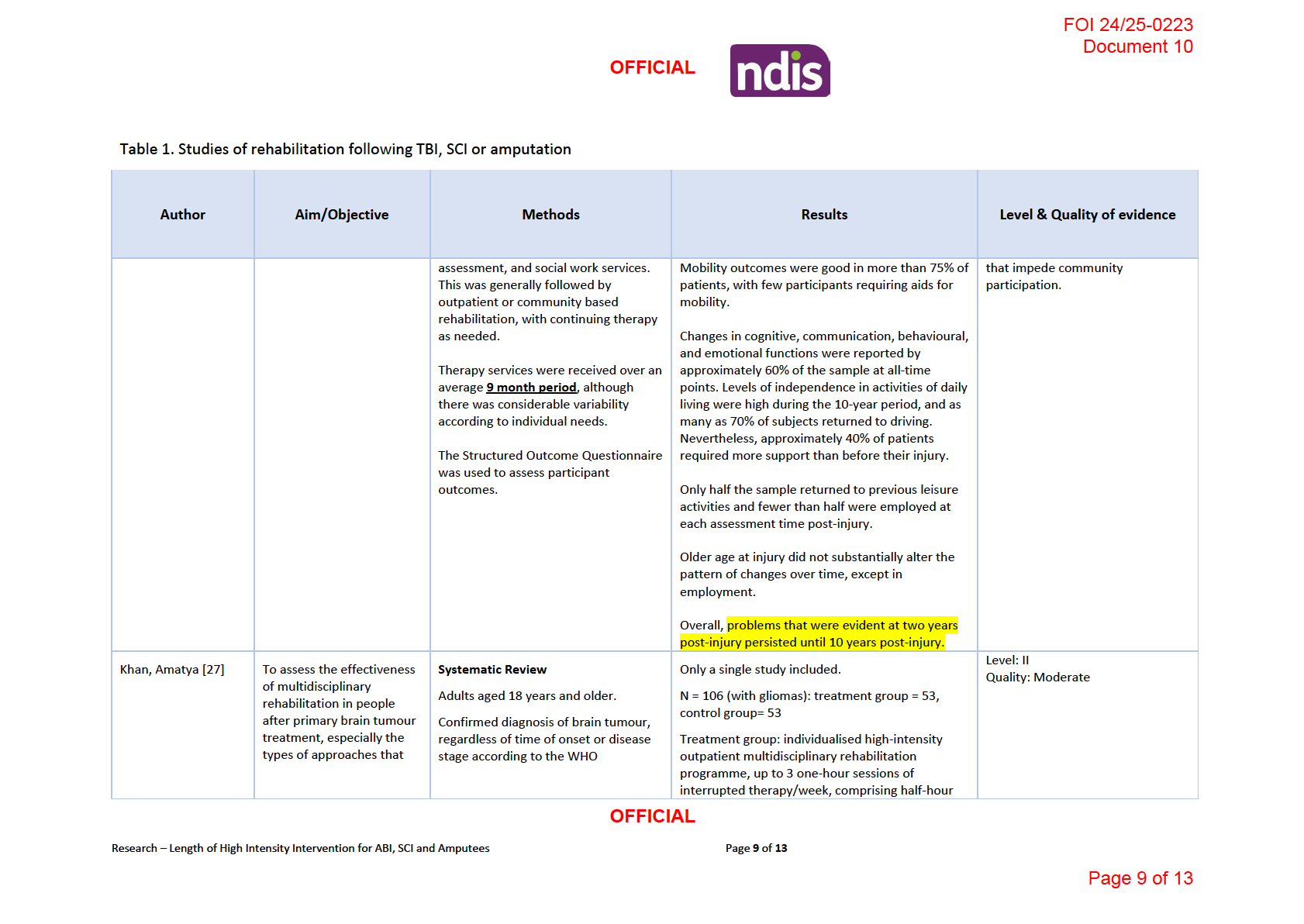

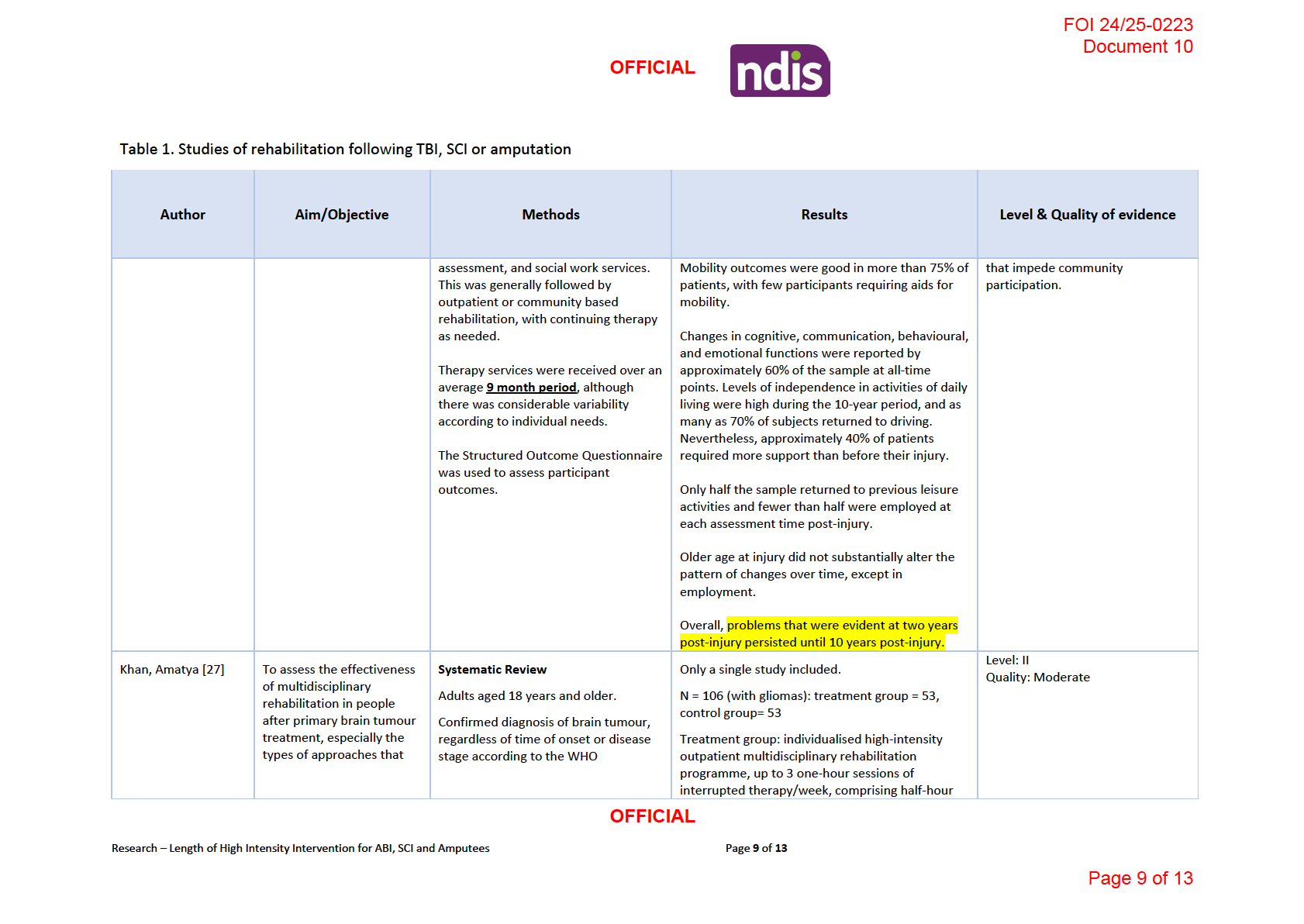

Downing [2] assessed patients at 2, 5 and 10 years post injury and found that problems that

were evident at two years post-injury persisted until 10 years post-injury.

Rate of improvement varies from person to person. Currently, we don’t know the exact

reason why the rate is different between people. However, age, pre-injury health, abilities

and severity of injury have an impact on recovery.

3.3 Impairment two years after brain injury

Research from the TBI Model System program offers information about recovery from a

moderate to severe TBI at 2 years after injury [15].

• About 30% of people need some amount of assistance from another person.

o This may be during the day, at night, or both. Over time, most people can

move around again without help.

• Trouble with thinking is common.

o This includes how fast a person can think. It also includes forming new

memories. The severity of these problems varies.

• About 25% of people have major depression.

o In some cases, it’s caused directly by the brain injury. In addition, people with

TBI are also dealing with major changes in their lives caused by the trauma,

including changes in employment, driving, and living circumstances.

• Just over 90% of people live in a private home.

o Of those who were living alone when they were injured, almost half go back

to living alone.

• About 50% of people can drive again, but there may be changes in how often they

drive or when.

• About 30% of people have a job, but it may not be the same job they had before the

injury.

4 Spinal Cord Injury

4.1

Length of time high therapy supports are effective

OFFICIAL

Research – Length of High Intensity Intervention for ABI, SCI and Amputees

Page

4 of

13

Page 4 of 13

FOI 24/25-0223

Document 10

OFFICIAL

A systematic review by Burns, Marino [16] sought to answer various questions relating the

type and timing of acute and subacute SCI. The results found that the evidence base is

limited for many fundamental questions related to rehabilitation fol owing acute and

subacute SCI and there is no agreement in relation to timing, intensity and response [16].

These knowledge gaps include the timing of rehabilitation, nature of rehabilitation (specific

interventions), therapeutic dose (intensity, frequency, and duration), role and impact of

patient and injury characteristics, cost-effectiveness and efficiency of alternative

interventions [16].

Of the studies included in the systematic review, the intervention lasted anywhere from 6 to

12 weeks [16]. This is likely because of similar reasons mentioned above for TBI (i.e. lack of

funding for trials). Fol ow up was up to 12 months.

Recommendations arising from this review include [17, 18]:

• Rehabilitation be offered to patients with acute SCI

when they are medical y stable

and can tolerate required rehabilitation intensity. (Grade: Weak Recommendation;

No included studies)

• Offer body weight–supported treadmill training as an option for ambulation training

in addition to conventional overground walking, dependent on resource availability,

context, and local expertise. (Grade: Weak Recommendation; Low Evidence)

• Individuals with acute and subacute cervical SCI be offered functional electrical

therapy as an option to improve hand and upper extremity function. (Grade: Weak

Recommendation; Low Evidence)

• Based on the absence of any clear benefit, suggest not offering additional training in

unsupported sitting beyond what is currently incorporated in standard

rehabilitation. (Grade: Weak Recommendation; Low Evidence)

4.2

Recovery Plateau

In the clinical management of spinal cord injury (SCI), neurological outcomes are generally

determined at 72 h after injury using American Spinal Cord Injury Association scoring system

[19]. This time-point has shown to provide a more precise assessment of neurological

impairments after SCI [20]. One important predictor of functional recovery is to determine

whether the injury was incomplete or complete. As time passes, SCI patients experience

some spontaneous recovery of motor and sensory functions. Most of the functional

recovery occurs during the first 3 months and in most cases reaches a plateau by 9 months

after injury [19, 21, 22]. However, additional recovery may occur up to 12–18 months post-

injury [19, 21, 22]. Long term outcomes of SCI are closely related to the level of the injury,

the severity of the primary injury and progression of secondary injury.

OFFICIAL

Research – Length of High Intensity Intervention for ABI, SCI and Amputees

Page

5 of

13

Page 5 of 13

FOI 24/25-0223

Document 10

OFFICIAL

5 Amputation

5.1

Length of time high therapy supports are effective

Unable to locate precise intensity and duration of multidisciplinary interventions for

amputees. However, the US Department of Veterans Affairs have developed a clinical

practice guideline for lower limb amputation [23]. For the purpose of the guideline, the

postoperative continuum is separated into “phases”. These include

1) Preoperative phase

2) Immediate postoperative phase

3) Pre-prosthetic rehabilitation phase

4) Prosthetic training phase. A study by Johannesson, Larsson [24] found that 64% of

participants obtained good function with their prosthesis within 6 months.

5) Rehabilitation and prosthesis fol ow up phase

The advancement through these phases is largely individualized, however the time needed

to progress is consistently reported to be between

12 and 18 months [23].

The NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation states that fol ow-up should occur regularly in the

initial period for example, fortnightly/monthly for a few months, then 3-monthly, then 6-

monthly [25]. Once the residual limb has stabilised, follow-up should occur, at minimum, on

an annual basis. This plan may vary depending on the needs of the person [25].

5.2

Recovery Plateau

Unable to locate any details relating to a recovery plateau for amputees in the literature. It

is clear however, the length of time often required before maintenance intervention should

be implemented.

OFFICIAL

Research – Length of High Intensity Intervention for ABI, SCI and Amputees

Page

6 of

13

Page 6 of 13

FOI 24/25-0223

Document 10

OFFICIAL

6 References

1.

Turner-Stokes L, Pick A, Nair A, Disler PB, Wade DT. Multi-disciplinary rehabilitation for

acquired brain injury in adults of working age. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015(12).

2.

Ponsford JL, Downing MG, Olver J, Ponsford M, Acher R, Carty M, et al. Longitudinal Fol ow-

Up of Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury: Outcome at Two, Five, and Ten Years Post-Injury. Journal

of Neurotrauma [Internet]. 2014 2014 Jan 01

2014-09-20; 31(1):[64-77 pp.]. Available from:

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/neu.2013.2997.

3.

Christensen BK, Colella B, Inness E, Hebert D, Monette G, Bayley M, et al. Recovery of

Cognitive Function After Traumatic Brain Injury: A Multilevel Modeling Analysis of Canadian

Outcomes. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation [Internet]. 2008 2008/12/01/; 89(12,

Supplement):[S3-S15 pp.]. Available from:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pi /S0003999308014986.

4.

Hammond FM, Grattan KD, Sasser H, Corrigan JD, Rosenthal M, Bushnik T, et al. Five years

after traumatic brain injury: A study of individual outcomes and predictors of change in function.

NeuroRehabilitation [Internet]. 2004; 19:[25-35 pp.].

5.

Hammond FM, Grattan KD, Sasser H, Corrigan JD, Bushnik T, Zafonte RD. Long-Term

Recovery Course After Traumatic Brain Injury: A Comparison of the Functional Independence

Measure and Disability Rating Scale. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation [Internet]. 2001;

16(4). Available from:

https://journals.lww.com/headtraumarehab/Ful text/2001/08000/Long Term Recovery Course Af

ter Traumatic Brain.3.aspx.

6.

Sbordone RJ, Liter JC, Pettler-Jennings P. Recovery of function fol owing severe traumatic

brain injury: A retrospective 10-year follow-up. Brain Injury [Internet]. 1995 1995/01/01; 9(3):[285-

99 pp.]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3109/02699059509008199.

7.

Whitlock JA, Hamilton BB. Functional outcome after rehabilitation for severe traumatic brain

injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation [Internet]. 1995 1995/12/01/; 76(12):[1103-

12 pp.]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pi /S0003999395801170.

8.

Davis Levere N, Levere TE. Recovery of function after brain damage: Support for the

compensation theory of the behavioral deficit. Physiological Psychology [Internet]. 1982

1982/06/01; 10(2):[165-74 pp.]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03332932.

9.

Choi SC, Barnes TY, Bul ock R, Germanson TA, Marmarou A, Young HF. Temporal profile of

outcomes in severe head injury. Journal of Neurosurgery [Internet]. 1994 01 Jan. 1994; 81(2):[169-73

pp.]. Available from: https://thejns.org/view/journals/j-neurosurg/81/2/article-p169.xml.

10.

Ponsford JL, Olver JH, Curran C. A profile of outcome: 2 years after traumatic brain injury.

Brain Injury [Internet]. 1995 1995/01/01; 9(1):[1-10 pp.]. Available from:

https://doi.org/10.3109/02699059509004565.

11.

Newcombe F. Very Late Outcome After Focal Wartime Brain Wounds. Journal of Clinical and

Experimental Neuropsychology [Internet]. 1996 1996/02/01; 18(1):[1-23 pp.]. Available from:

https://doi.org/10.1080/01688639608408258.

12.

Dams-O'Connor K, Ketchum JM, Cuthbert JP, Corrigan JD, Hammond FM, Haarbauer-Krupa J,

et al. Functional Outcome Trajectories Following Inpatient Rehabilitation for TBI in the United States:

A NIDILRR TBIMS and CDC Interagency Col aboration. J Head Trauma Rehabil [Internet]. 2020

Mar/Apr PMC6814509]; 35(2):[127-39 pp.].

OFFICIAL

Research – Length of High Intensity Intervention for ABI, SCI and Amputees

Page

11 of

13

Page 11 of 13

FOI 24/25-0223

Document 10

OFFICIAL

13.

Millar K, Nicoll JAR, Thornhill S, Murray GD, Teasdale GM. Long term neuropsychological

outcome after head injury: relation to APOE genotype. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery

& Psychiatry [Internet]. 2003; 74(8):[1047 p.]. Available from:

http://jnnp.bmj.com/content/74/8/1047.abstract.

14.

Olver JH, Ponsford JL, Curran CA. Outcome fol owing traumatic brain injury: a comparison

between 2 and 5 years after injury. Brain Injury [Internet]. 1996 1996/01/01; 10(11):[841-8 pp.].

Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/026990596123945.

15.

Center MSKT. Understanding TBI: Part 3 - The Recovery Process 2019 [Available from:

https://msktc.org/tbi/factsheets/Understanding-TBI/The-Recovery-Process-For-Traumatic-Brain-

Injury.

16.

Burns AS, Marino RJ, Kalsi-Ryan S, Middleton JW, Tetreault LA, Dettori JR, et al. Type and

Timing of Rehabilitation Fol owing Acute and Subacute Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review.

Global Spine Journal [Internet]. 2017 2017/09/01; 7(3_suppl):[175S-94S pp.]. Available from:

https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568217703084.

17.

Fehlings MG, Tetreault LA, Aarabi B, Anderson P, Arnold PM, Brodke DS, et al. A Clinical

Practice Guideline for the Management of Patients With Acute Spinal Cord Injury: Recommendations

on the Type and Timing of Rehabilitation. Global spine journal [Internet]. 2017; 7(3 Suppl):[231S-8S

pp.]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5684839/.

18.

Fehlings MG, Tetreault LA, Wilson JR, Kwon BK, Burns AS, Martin AR, et al. A Clinical Practice

Guideline for the Management of Acute Spinal Cord Injury: Introduction, Rationale, and Scope.

Global spine journal [Internet]. 2017; 7(3 Suppl):[84S-94S pp.]. Available from:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5684846/.

19.

Kehr P, Kaech DL. Michael G. Fehlings, Alexander R. Vaccaro, Maxwell Boakye, Serge

Rossignol, John F. Ditunno Jr, Anthony S. Burns: Essentials of spinal cord injury: basic research to

clinical practice. European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery & Traumatology. 2014;24(5):837-.

20.

Brown PJ, Marino RJ, Herbison GJ, Ditunno JF, Jr. The 72-hour examination as a predictor of

recovery in motor complete quadriplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1991;72(8):546-8.

21.

Alizadeh A, Dyck SM, Karimi-Abdolrezaee S. Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury: An Overview of

Pathophysiology, Models and Acute Injury Mechanisms. Frontiers in Neurology [Internet]. 2019

2019-March-22; 10(282). Available from:

https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fneur.2019.00282.

22.

Burns AS, Marino RJ, Flanders AE, Flett H. Chapter 3 - Clinical diagnosis and prognosis

fol owing spinal cord injury. In: Verhaagen J, McDonald JW, editors. Handbook of Clinical Neurology.

109: Elsevier; 2012. p. 47-62.

23.

The Rehabilitation of Lower Limb Amputation Working Group. Clinical Practice Guideline For

Rehabilitation of Lower Limb Amputation. Washington; 2007. Available from:

https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Rehab/amp/amp v652.pdf#page=75.

24.

Johannesson A, Larsson G-U, Ramstrand N, Lauge-Pedersen H, Wagner P, Atroshi I.

Outcomes of a Standardized Surgical and Rehabilitation Program in Transtibial Amputation for

Peripheral Vascular Disease: A Prospective Cohort Study. American Journal of Physical Medicine &

Rehabilitation [Internet]. 2010; 89(4). Available from:

https://journals.lww.com/ajpmr/Ful text/2010/04000/Outcomes of a Standardized Surgical and.4

.aspx.

25.

NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation. ACI Care of the Person following Amputation: Minimum

Standards of Care Australia; 2017. Available from:

https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/ data/assets/pdf file/0019/360532/The-care-of-the-person-

following-amputation-minimum-standards-of-care.pdf.

26.

Königs M, Beurskens EA, Snoep L, Scherder EJ, Oosterlaan J. Effects of Timing and Intensity

of Neurorehabilitation on Functional Outcome After Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review and

OFFICIAL

Research – Length of High Intensity Intervention for ABI, SCI and Amputees

Page

12 of

13

Page 12 of 13

FOI 24/25-0223

Document 10

OFFICIAL

Meta-Analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation [Internet]. 2018 2018/06/01/;

99(6):[1149-59.e1 pp.]. Available from:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pi /S0003999318300868.

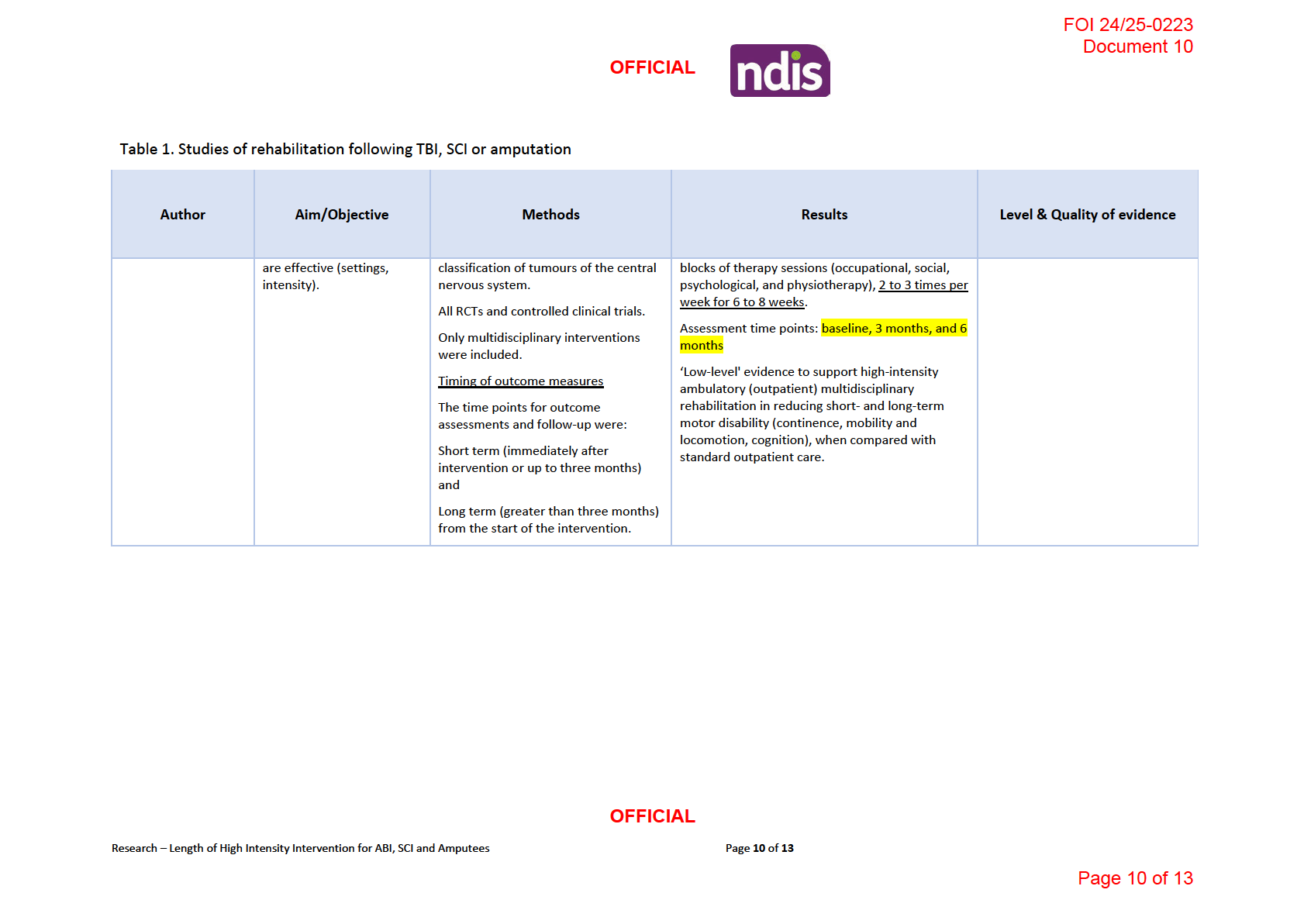

27.

Khan F, Amatya B, Ng L, Drummond K, Galea M. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation after primary

brain tumour treatment. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015(8).

OFFICIAL

Research – Length of High Intensity Intervention for ABI, SCI and Amputees

Page

13 of

13

Page 13 of 13