FOIREQ24/00508 0184

Style Guide

Prepared by Strategic Communications

16 June 2021

FOIREQ24/00508 0186

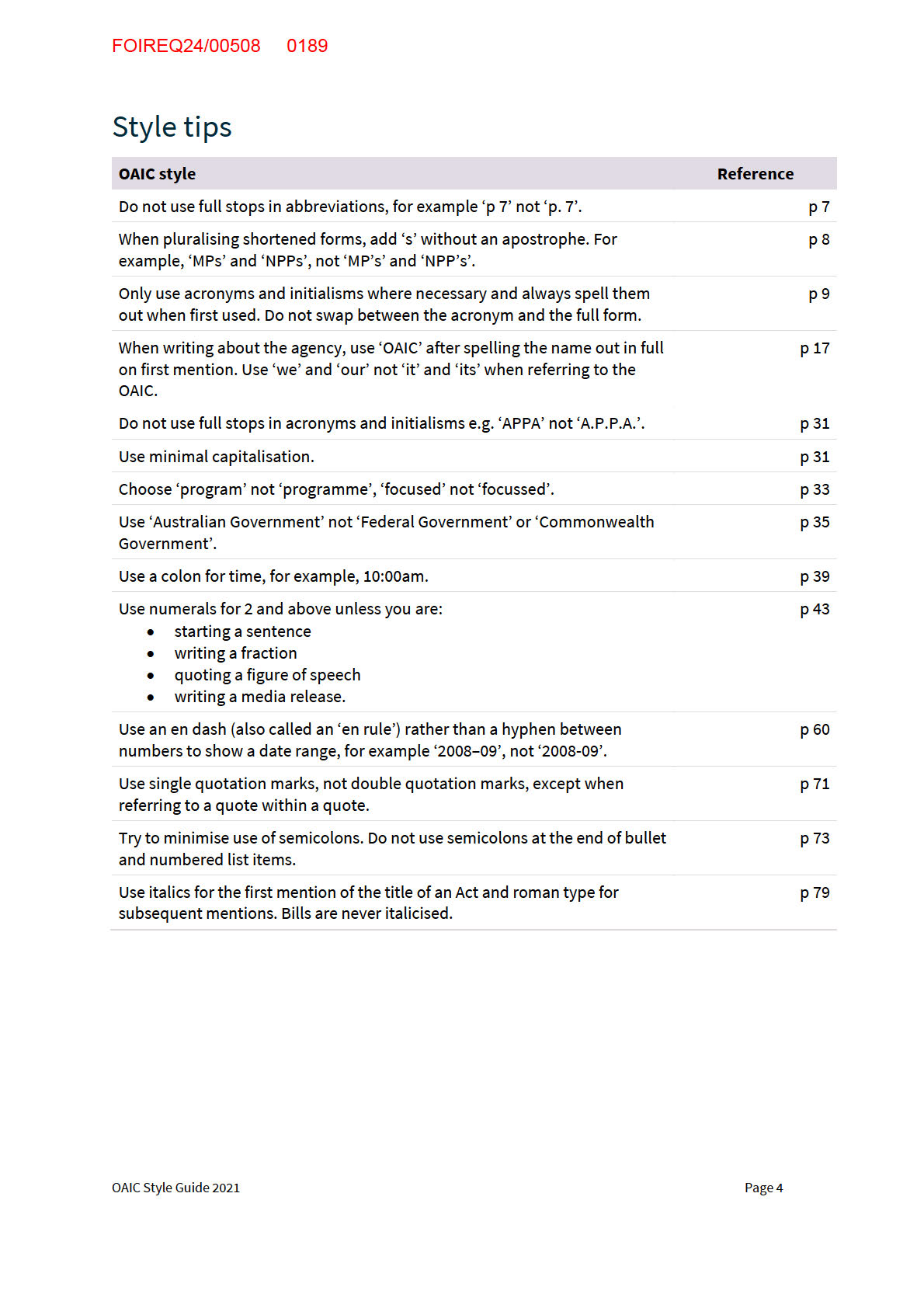

Welcome to the new OAIC Style Guide

The Strategic Communications team is pleased to share the new OAIC Style Guide, which replaces

the 2012 Writing style guide. The Style Guide provides comprehensive guidance whether you’re

writing a webpage, report, submission or presentation. We encourage you to familiarise yourself

with the content of our Style Guide – and use it to resolve your queries about writing style.

We welcome your feedback on the Style Guide. Tell us how we can make the Style Guide more

helpful – and let us know what’s missing – by emailing us at xxxxxxxxx@xxxx.xxx.xx.

Structure

The OAIC Style Guide has been structured in the same way as the Australian Government digital

Style Manual which was released in September 2020.

Style Guide content has been linked to the digital Style Manual so you can access more detailed

information easily.

Blue boxes summarise content sections.

Yellow boxes highlight useful information and tips.

Grey boxes provide examples.

Links in the Style Guide point to:

1. Further guidance in the Style Guide

2. Guidance in the digital Style Manual

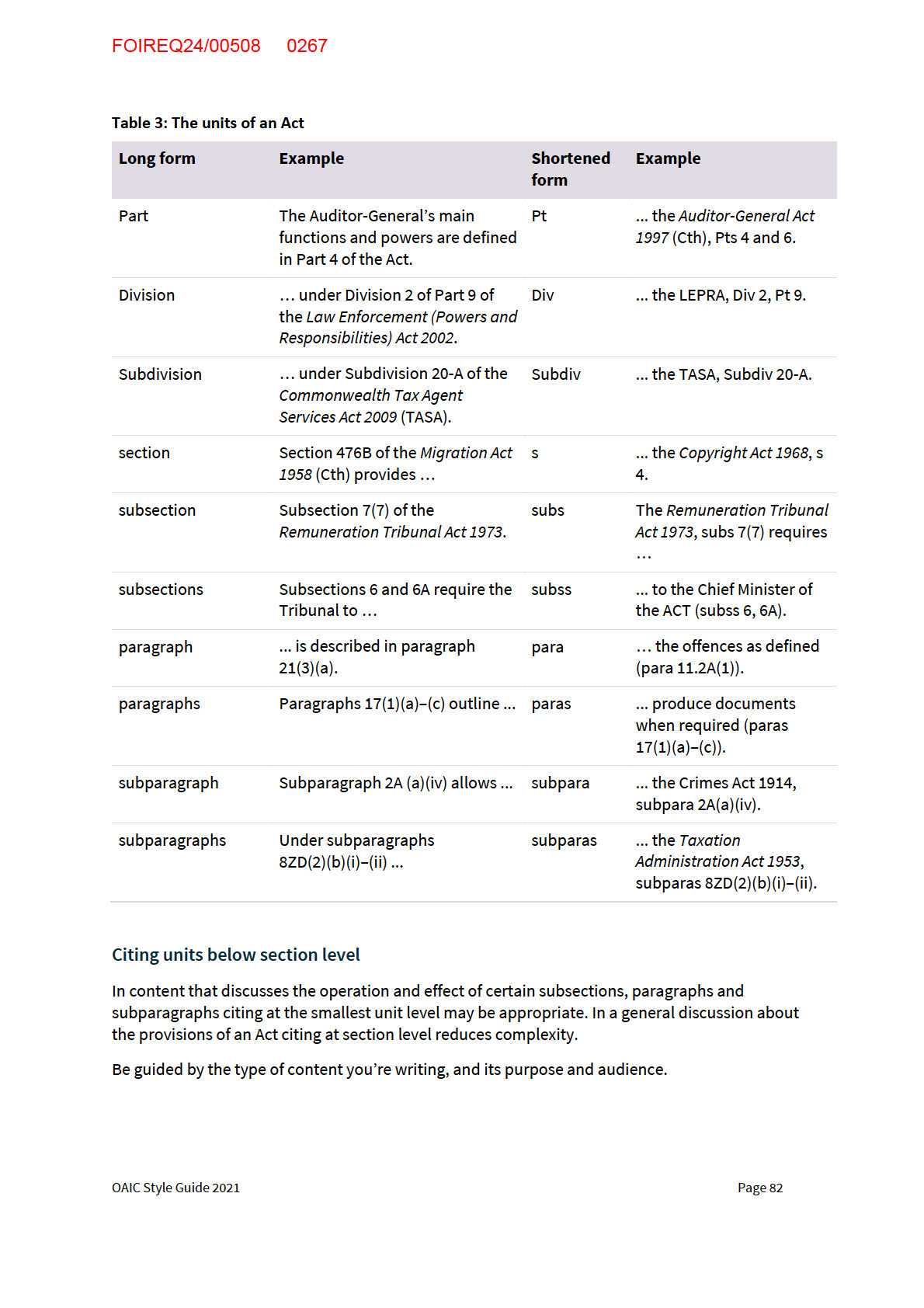

Legal citations

This Style Guide contains guidance on how to cite legal material which is tailored to the content

we publish, such as guidance and advice, reports and assessments. See Legal material below.

For specific guidance on how to cite legal material in legal writing and research, you may wish to

use the 4th edition of the

Australian Guide to Legal Citation (AGLC4).

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 1

FOIREQ24/00508 0187

Contents

Part A: Format, writing and structure

5

Clear language and writing style

5

Plain language and word choice

5

Abbreviations

7

Acronyms and initialisms

8

Contractions

10

Latin shortened forms

11

Sentences

12

Types of words

14

Voice and tone

15

Inclusive language

18

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

18

Age diversity

19

Cultural and linguistic diversity

19

Gender and sexual diversity

20

People with disability

22

Structure

23

Types of structure

23

Headings

24

Links

26

Lists

27

Paragraphs

29

General conventions, editing and proofreading

30

Part B: Style rules and conventions

30

Editing and proofreading

30

Italics

30

Punctuation and capitalisation

32

Spelling

33

Names and terms

35

Australian place names

35

Government terms

36

Commercial terms

38

Dates and time

38

Organisation names

41

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 2

FOIREQ24/00508 0188

Numbers and measurement

44

Choosing numerals or words

44

Currency

46

Measurements and units

46

Ordinal numbers

47

Percentages

47

Punctuation marks

49

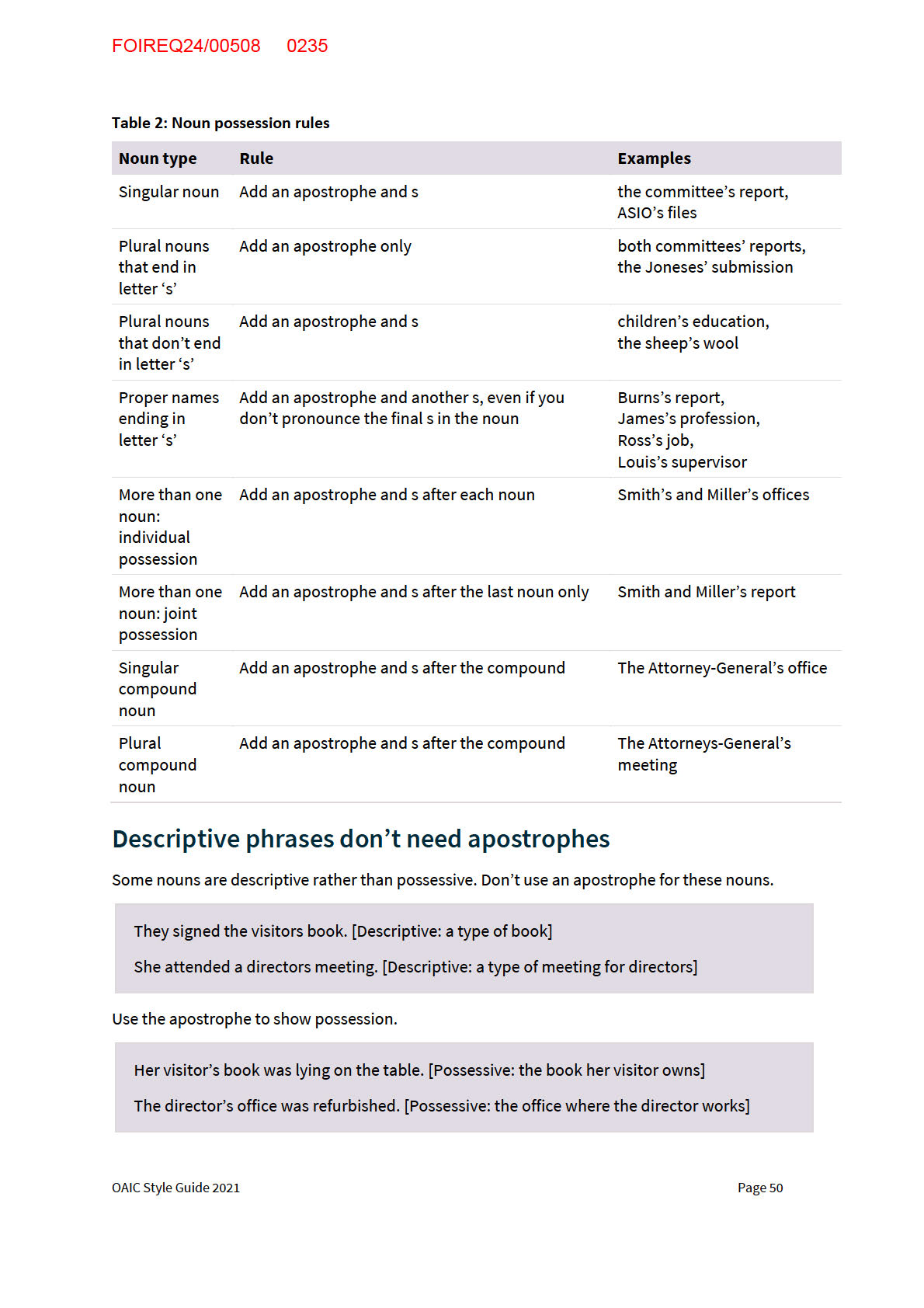

Apostrophes

49

Brackets and parentheses

52

Colons

54

Commas

55

Dashes and en dashes

60

Exclamation marks

63

Ellipses

63

Forward slashes

64

Full stops

64

Hyphens

66

Question marks

70

Quotation marks

71

Semicolons

73

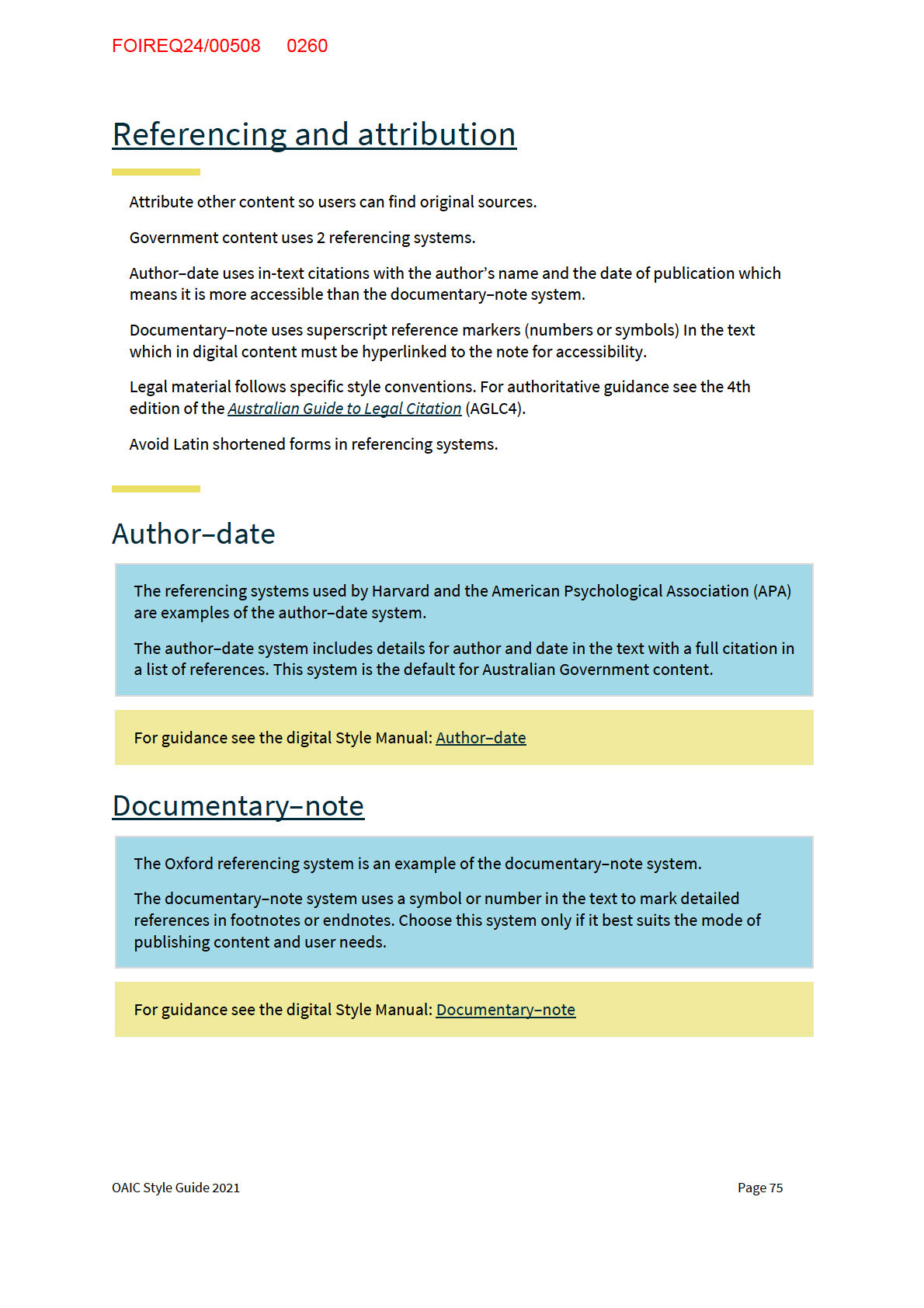

Referencing and attribution

75

Author–date

75

Documentary–note

75

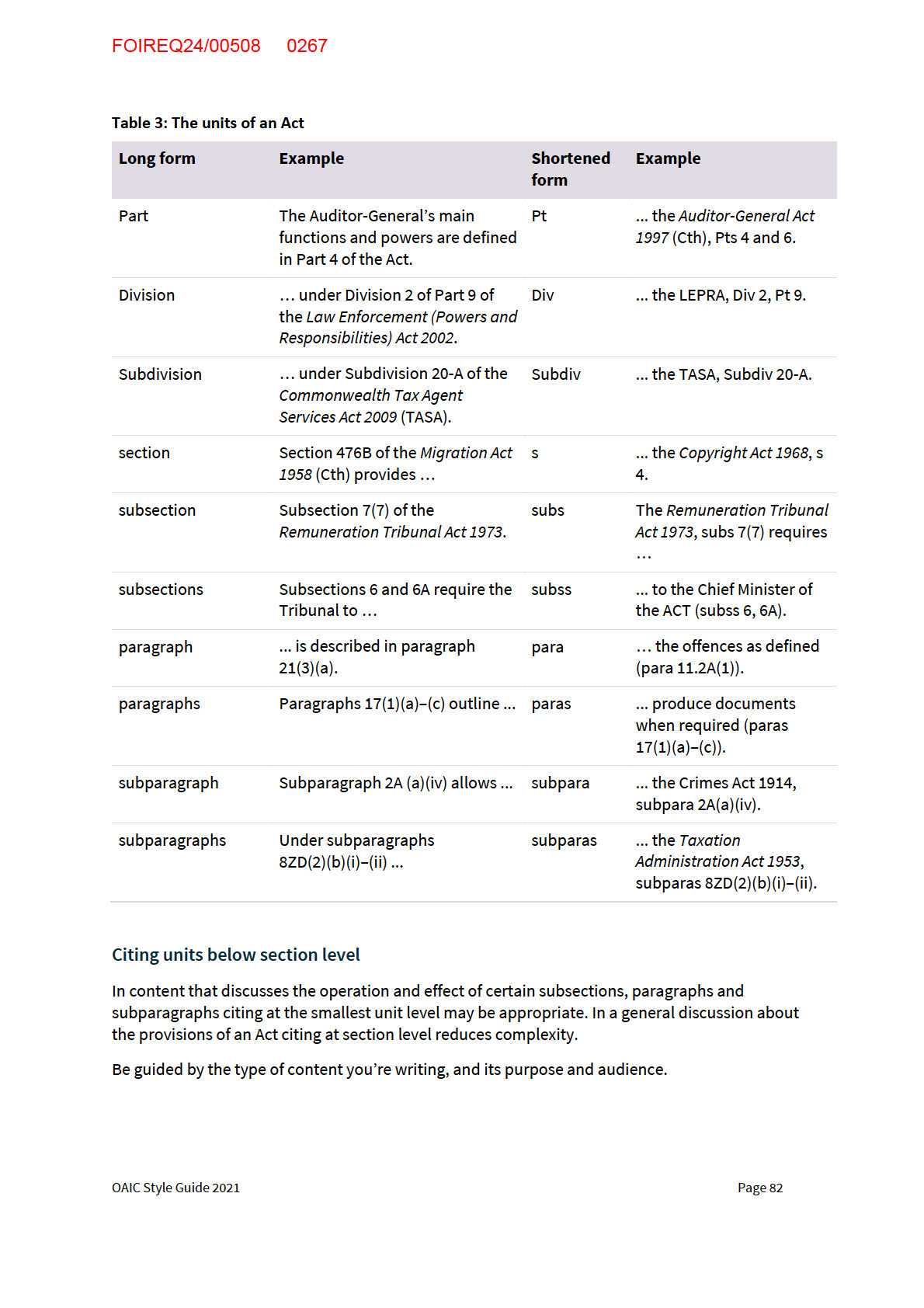

Legal material

76

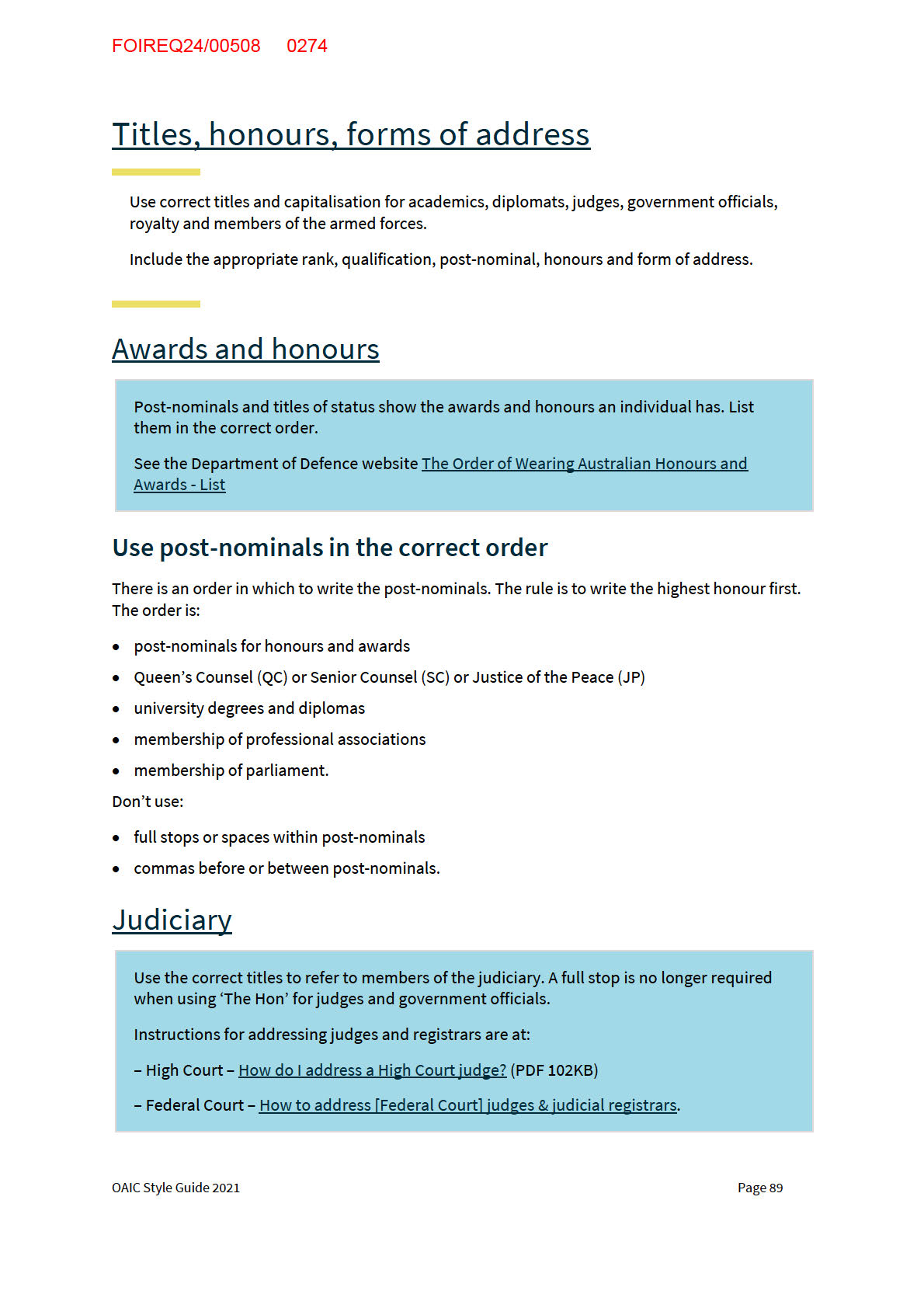

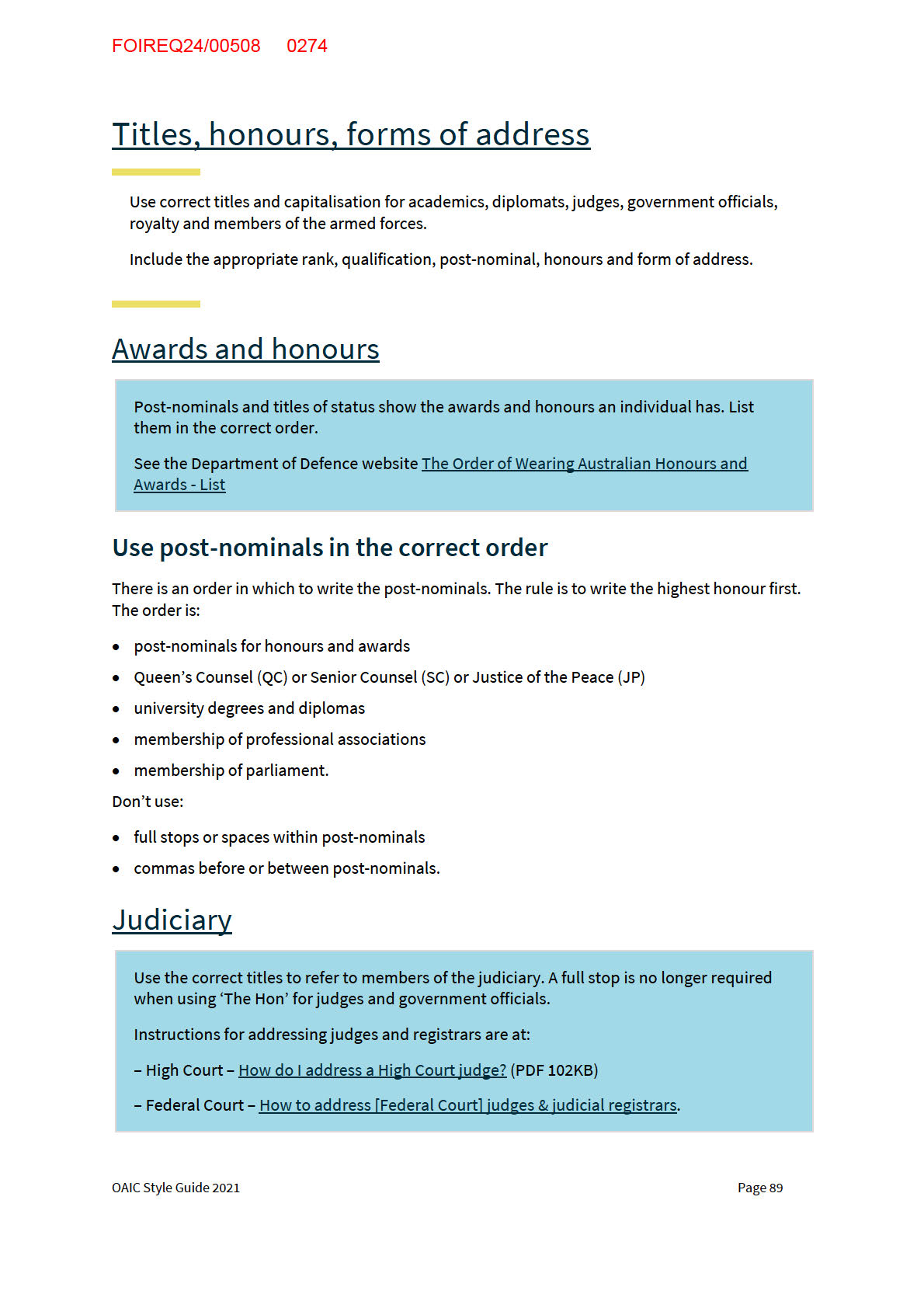

Titles, honours, forms of address

89

Awards and honours

89

Judiciary

89

Members of Australian parliaments and councils

90

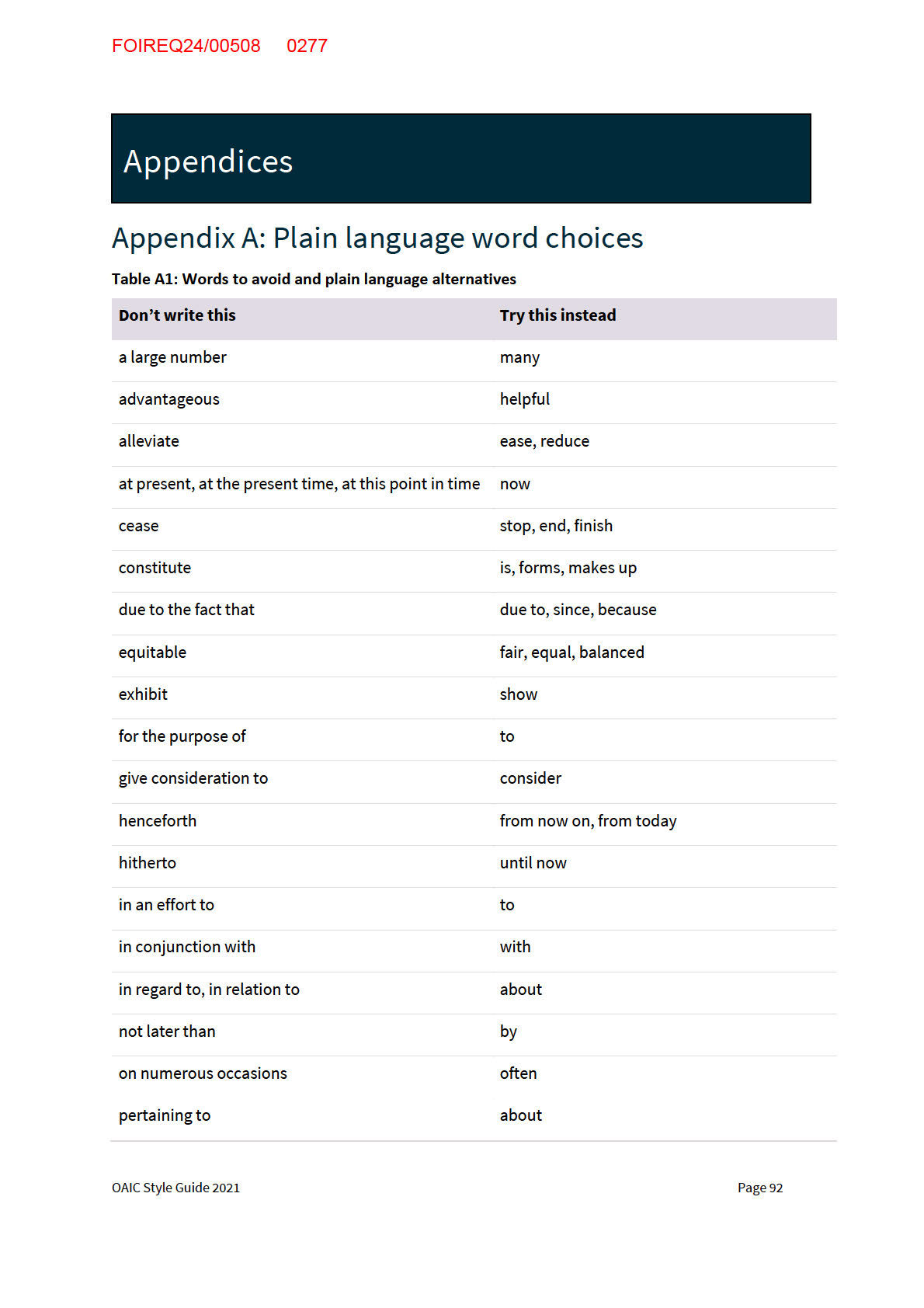

Appendices

92

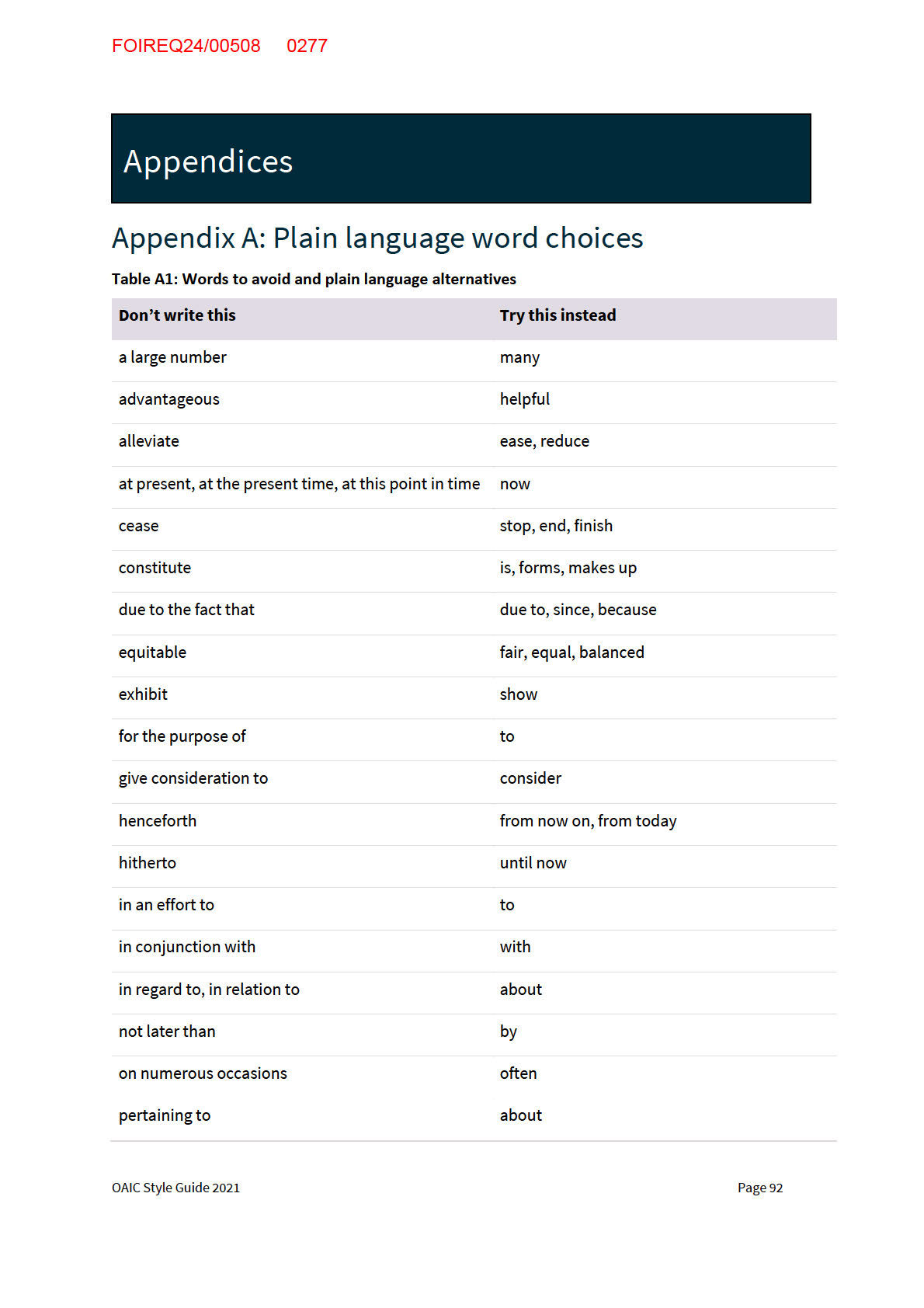

Appendix A: Plain language word choices

92

Appendix B: Abbreviations

94

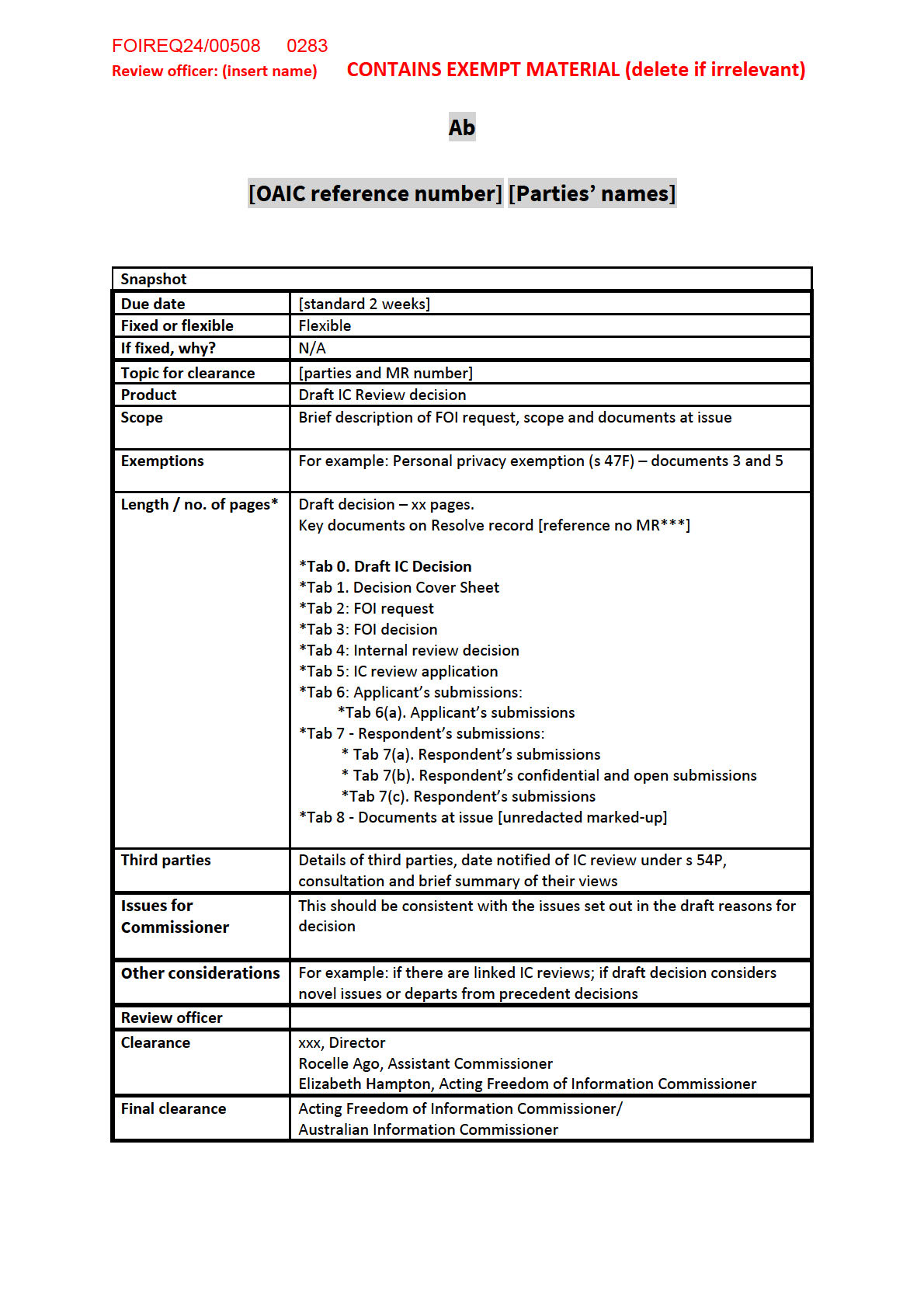

Appendix C: OAIC templates

97

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 3

FOIREQ24/00508 0191

Write this

We will assess your application in 30 days.

Not this

Applications are assessed in 30 days.

Passive voice

Only use the passive when:

• you have to be diplomatic and the active would sound too direct

• you have one subject that you would otherwise repeat endlessly.

Use inclusive language

People can relate to content when it uses inclusive language. Choose words that respect all

people, including their rights and their heritage.

Use language that is culturally appropriate and respectful of the diversity of Australia’s

peoples.

Only refer to age when it is relevant and necessary.

Use gender-neutral language and preferred pronouns.

Focus on the person, not the disability. Mention disability only if it is relevant and

necessary.

Choose simple words, not complicated expressions

There is usually more than one way to express something. Find the simplest, clearest option.

Replace longer words and phrases with simpler alternatives. See Appendix A: Plain language word

choices.

Keep words and phrases with special meaning to a minimum

People can be unfamiliar with words you need to use, for example:

• official titles

• Acts of parliament

• names of organisations.

For names and terms with special meaning, follow style rules and conventions.

Be selective about shortened forms, such as abbreviations, acronyms and initialisms.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 6

FOIREQ24/00508 0192

Shorten only words and phrases that are well known or used many times in your content.

Always consider user needs and avoid using shortened forms when writing for the public

which may be seen as jargon.

The Australian Privacy Principles are principles-based law.

Consumer Data Right

The Consumer Data Right was introduced on 1 July 2020. To help consumers become

familiar with the concept, government agencies have been asked to use the term in full

wherever possible. The initialism ‘CDR’ may be used to refer to specific elements of system –

for example, the CDR Rules, CDR Privacy Safeguards and CDR data – or where space for

content is limited, such as in headings.

Shortened forms can help people read and understand content, but too many can be difficult to

follow. In content with many specialist terms, reserve shortened forms for the most frequently

used terms only. Spell out other terms in full.

Spell out shortened forms the first time you use them. In a long publication, spell them out

at the beginning of each section.

The Notifiable Data Breaches (NDB) scheme began on 22 February 2018.

Abbreviations

Abbreviations are shortened words. They can hinder people’s understanding, so they have

limited uses.

Limit the use of abbreviations

Abbreviations contain the first single letter or first few letters of a word. They don’t include the last

letter of a word.

cont (for continued)

fig (for figure)

p (for page)

tel (for telephone)

para (for paragraph)

co (for company)

Abbreviations are generally not good for readability and can be misunderstood. Avoid using them

in general text where possible.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 7

FOIREQ24/00508 0193

Abbreviations are useful in very limited circumstances:

• in a table or chart, where space is unavailable for the full form of the word – provide a note

under the table or chart giving the full form

• when using ‘cont’ to show continuing text in another part of content (for example, on another

page of a print newsletter) – the full form of the word is more helpful where space allows.

Don’t put a full stop after most abbreviations

Don’t place a full stop after an abbreviation unless it ends the sentence.

See Organisation names

See Months and days of the week

Unlike other shortened forms, some Latin shortened forms have full stops.

Place full stops after each letter in ‘i.e.’ and ‘e.g.’ so that screen readers can announce them.

Do not use a comma after ‘e.g.’ or ‘i.e.’ in a sentence.

Add ‘s’ to create plural abbreviations

Add an ‘s’. There is no need for an apostrophe.

APPs

MPs

Acronyms and initialisms

Acronyms and initialisms are shortened forms. They replace full names and special terms in

text. Use them only if people recognise and understand them.

See Appendix B: Abbreviations

Choose acronyms and initialisms people will recognise.

Acronyms are terms that comprise initial letters and you can pronounce as a word.

Qantas

Anzac

TAFE

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 8

FOIREQ24/00508 0194

Initialisms are terms that comprise initial letters and you pronounce as letters, not a word.

CDR

GST

NDIS

Acronyms and initialisms are common in formal content. If understood by users, they can make

content easier to use.

CSIRO for ‘Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation’

Explain acronyms and initialisms to all users

People unfamiliar with certain terms might not understand their shortened forms. Acronyms and

initialisms might also be misread by screen readers.

Spell out acronyms and initialisms the first time you use them. In a long publication, spell

them out at the beginning of every section.

The Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) sent a letter to the client in June.

Check the correct shortened form for government organisations

The names of government departments are often shortened, but not always in the same way.

DFAT (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade)

Home Affairs (Department of Home Affairs)

Rather than using acronyms or initialisms, it can be easier for people if you:

• spell out the agency’s name in full the first time you use it

• then use the generic name (‘department’, ‘agency’, ‘bureau’) afterwards.

For content with lots of acronyms and initialisms, provide a glossary at the end or on a

separate webpage. Use a hyperlink in the text to help people access the glossary.

Don’t end acronyms and initialisms with a full stop

Don’t place a full stop after the acronym or initialism unless it ends a sentence.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 9

FOIREQ24/00508 0195

Use capitals for most acronyms and initialisms

If the acronym or initialism represents common nouns, don’t begin each word of the full form with

a capital letter.

‘privacy impact assessment’ for PIA

‘privacy management plan’ for PM

‘tax file number’ for TFN

If the acronym or initialism represents a proper noun, start each word with a capital letter

(excluding words such as ‘of’ and ‘and’).

OPC [Office of Parliamentary Counsel]

Avoid plural and possessive forms on the first use

Avoid using the plural or possessive of an acronym or initialism when you define it. This makes it

easy for users to recognise the shortened form in later content.

It’s compulsory for certain businesses to have an Australian Business Number (ABN). The

Australian Business Register manages applications for ABNs. [There’s no need to use an

apostrophe before the ‘s’ for ABNs as the term is plural, not possessive.]

The Australian National University (ANU) has a new student policy. The ANU’s policy is

popular with its staff and students. [Use an apostrophe before the ‘s’ to show that the ANU

owns the policy.]

Contractions

Contractions are shortened words. People will read and understand them depending on

their context. Avoid them in formal content.

Shorten single words and grammatical phrases with care

Single-word contractions use the first and last letters of a word and sometimes other letters in

between. Avoid using contractions of single words in more formal content such as ministerial

briefings. The exceptions are contractions such as ‘Dr’ and other titles.

Cth for ‘Commonwealth’

Ltd for ‘Limited’

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 10

FOIREQ24/00508 0196

Don’t place a full stop after contractions. The exception is when the contraction ends a sentence

and isn’t followed by another punctuation mark.

Number is shortened to ‘no.’ in legislation titles and a full stop is used after the contraction.

This is an exception to the rule that a full stop should not be placed after a contraction

unless the contraction ends the sentence.

Grammatical contractions join 2 words. They use an apostrophe to show that there are missing

letters.

aren’t (are not)

don’t (do not)

isn’t (is not)

it’s (it is)

See Apostrophes show contractions

Grammatical contractions are not generally used in formal content. You can use them in less

formal content which aims to create:

• a conversational tone (for example, in a newsletter)

• a friendly or collaborative tone (for example, in manuals).

Don’t end contractions with full stops

Don’t place a full stop after contractions. The exception is when the contraction ends a sentence

and isn’t followed by another punctuation mark.

Latin shortened forms

Use English rather than Latin shortened forms, except in some cases.

Rather than using ‘e.g.’ or ‘i.e.’ write the English words out in full. Write ‘for example’ and

‘that is’ instead, particularly in more formal publications.

Where you need to show an error in a quotation, use ‘[

sic]’ which means ‘in the original’. Place it

directly after the error.

Written late at night, the report began, ‘The office was previously in Melberne [

sic].’

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 11

FOIREQ24/00508 0197

Sentences

Clear sentences in active voice improve readability. Keep sentences short to help people

scan content.

Write plain language sentences

Keep sentences to an average of 15 words and no more than 25 words, especially for digital

content. Too many words, phrases and clauses affect people’s ability to scan sentences.

Sentences over 25 words can usually be broken up using different techniques, like using lists.

Use active voice

Use active rather than passive voice. Active voice helps users understand who is doing what. It can

also help people know exactly what their responsibility is.

Eligible students can access the subsidy by completing the application. [Active voice]

The subsidy can be accessed by completing the application. [Passive voice]

The difference is clearest with action verbs:

• Active voice: the grammatical subject is performing the action in a sentence.

• Passive voice: the grammatical subject is undergoing the action.

Active voice: The student filed the application. [‘The student’ is the grammatical subject,

who did the filing. ‘The application’ is the object.]

Passive voice: The application was filed by the student. [‘The application’ is the

grammatical subject, but did not do the filing.]

Construct positive, unambiguous sentences

Words, phrases and sentences can have more than one meaning. Write exactly what you mean and

construct your sentences so there is no ambiguity. Write sentences so they are positive rather than

negative.

Like this

Include these documents when you apply.

Not this

You can’t submit your application if you don’t include these documents.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 12

FOIREQ24/00508 0198

Avoid double negatives

Double negatives can lead to misunderstandings, so avoid them.

Write this

It was acceptable …

Not this

It was not unacceptable …

Eliminate unnecessary words

Make each word work for its place in the sentence. Sentence structure is clearer if each word plays

a necessary role. Clear sentences improve readability.

Be precise

Avoid unnecessary words. Keep the words needed to make meaning clear.

Avoid using ‘there is’ and ‘there are’ when they only add extra words and not meaning.

Vary sentence structure

Vary your sentence structure to suit the content.

Sentence structures can be simple, compound or complex.

Simple sentence structures are easier to scan. People understand meaning through the order of

words in a sentence. A simple sentence construction has fewer parts to take in.

Compound and complex sentences can add variety and flow to your writing. Sentences should still

be easy to scan, even using these structures.

Complex structure is harder to follow, regardless of a person’s literacy level. Complex structures

take more effort to read, even if they are punctuated properly.

Build simple phrases and clauses

Sentences consist of phrases and clauses. Each group of words carries out a different function.

Some common constructions used in bureaucratic writing are complex and unnecessary. They

add words but not meaning.

Instead of bureaucratic language, use plain language and word choice.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 13

FOIREQ24/00508 0199

Types of words

Keep the functions of words in mind to write clear content. Grammar and sentence

structure help people understand meaning.

Functional categories for words are also known as ‘parts of speech’.

Words are grouped by function

Each word has a function in a sentence, clause or phrase. You can group words into different types

depending on the way they function.

You can group words into different types depending on the way they function. See the

digital Style Manual for guidance on:

– adjectives

– adverbs

– conjunctions

– determiners

– nouns

– prepositions

– pronouns

– verbs.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 14

FOIREQ24/00508 0200

Voice and tone

Writing style is a result of voice and tone. Adjust your style to meet user needs. It influences

whether and how people engage with content.

Adapt writing style with tone and voice

Writing style describes the way you express ideas in content. The tone and voice you use influence

the writing style for any type of content.

Tone is the way you express ideas. It includes the words you use, the way you put them together

and their level of formality.

Voice captures who is writing – a persona people understand when they engage with the content.

Voice can be objective and institutional or personal and friendly.

Adapt tone and voice to engage users, so the content can meet their needs. For example, briefs for

ministers will use a different tone and voice to a speech or information on a website.

Choose how formal tone should be

The appropriate level of formality depends on what the relationship is between content and its

user. There are 3 levels of formality:

• formal

• standard

• informal.

A formal tone creates a distance between the content’s persona and the user.

An informal tone suggests a relationship that is more casual and intimate.

A standard tone sits between these 2. It is appropriate for most government content.

Formal tone

Formal tone:

• doesn’t use contractions

• is literal – words are used with their dictionary meaning

• doesn’t use metaphor, slang or idioms

• often uses the third person (he, she, they, them).

Legal writing, policies, reports and ministerial letters often adopt a formal tone. You can also use it

in emails and letters when you have not yet met the person you are writing to.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 15

FOIREQ24/00508 0201

Standard tone

Standard tone combines formal and informal tone. Most people find standard tone easiest to

understand.

Standard tone:

• can use contractions and personal pronouns

• doesn’t use metaphors, idioms or slang.

You will probably use standard tone for most government content. This includes:

• emails and letters

• online government services

• corporate communications

• media releases

• articles.

Informal tone

Informal tone uses contractions and personal pronouns.

Informal tone can use metaphors and idioms, which can have a negative effect on inclusion.

Metaphors and idioms are not plain language.

You should not use slang when writing on behalf of government.

Informal tone is used in social media and blogs. Your writing might also become more informal as

you get to know the people you are writing to.

You can lighten the tone of your writing, especially for the public, by including personal

pronouns, such as ‘we’ and ‘our’. This will also help you to create a more inclusive tone.

Where you are writing to a specific reader, such as in a letter, consider using ‘I’ and ‘you’.

Using a lighter tone does not mean leaving out technical language that is essential to your

content.

The government voice

A basic government voice is a ‘definitive source’ and is respectful, clear and direct, objective and

impartial.

A respectful writing style:

• uses inclusive language

• expresses ideas in everyday words

• ‘speaks’ to people – using the pronoun ‘you’, for example

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 16

FOIREQ24/00508 0202

• doesn’t use inflammatory language, such as name-calling or sarcasm

• doesn’t speak down to people, but isn’t too familiar either.

A clear and direct writing style:

• is in plain language

• uses active voice

• is concise

• structures ideas

• makes it easy for people to understand what they need to know or do.

Objective and impartial writing:

• relies on facts

• doesn’t include opinion

• is balanced and non-biased.

The difference between fact and opinion can be subtle.

Viewpoint affects perception of whether information is neutral or impartial. Adjectives and

adverbs can also affect whether the information comes across as fact or opinion.

Mixing personal pronouns with ‘the OAIC’ will bring variety and warmth to your writing.

On our website and in our corporate publications, we use ‘we’ and ‘our’ when referring to

the OAIC, instead of using ‘its’ which sounds more formal.

We use ‘organisation or agency’ and not ‘entity’ on our website. We use ‘they and not ‘it’

when referring to an organisation or agency in the third person.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 17

FOIREQ24/00508 0204

The digital Style Manual significantly revises and updates guidance on content that relates

to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

For example, the sixth edition described the term ‘Indigenous’ as ‘widely acceptable’ as a

subset of the broader term ‘Australian’. The latest, digital edition cautions that use of the

term ‘Indigenous’ can be inaccurate without proper context.

See digital Style Manual: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

Age diversity

Refer to age only if it is necessary. Use respectful language and consistent style if age is

relevant.

If age is relevant, follow style conventions

Question whether age is relevant. Avoid referring to a person’s age or an age group if it’s not

relevant.

If you need to mention age, follow style conventions:

• when the reference to age comes before a noun, punctuate it with hyphens

• unless the age reference begins a sentence, use numerals.

A 39-year-old man faces court today on several charges.

You can withdraw your super once you’re 65, even if you’re still working.

Fourteen-year-old Jasmine Greenwood is the youngest Australian on the Paralympic Games

squad.

Cultural and linguistic diversity

Australians have different cultural backgrounds and speak many languages. Use inclusive

language that respects this diversity.

Speak to the person, not their difference

Use inclusive language. You can use the general term ‘multicultural communities’ to write about

people from different cultural backgrounds.

People writing for government sometimes use the term ‘culturally and linguistically diverse’

(CALD) communities. Avoid using the acronym unless you’re speaking to a specialist audience.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 19

FOIREQ24/00508 0205

Use respectful and inclusive language that talks to the person, not their difference. In

Australia, it’s the law. Commonwealth laws include:

–

Racial Discrimination Act 1975

–

Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986 –

Public Service Act 1999.

Use the terms ‘given name’ and ‘family name’

Many naming systems around the world differ from those used in English-speaking countries.

Given names come before family names in English-speaking countries. In some Asian cultures,

people write the family name first.

When you ask people their name, don’t ask for ‘Christian name’, ‘first name’, ‘forename’ or

‘surname’. Instead, ask for their:

• given name

• family name.

Gender and sexual diversity

Inclusive language conveys gender equality and is gender-neutral. Respect peoples’

preferences around gender and sexual identity with pronoun choice and job titles.

Use gender-neutral language

Use terms that recognise gender equality. Avoid terms that discriminate on the basis of a person’s

gender or sexual identity.

Our use of language reflects changes in society. There is wide agreement about using language to

support equality between all genders.

It is unlawful to discriminate against a person under the

Sex Discrimination Act 1984. This

discrimination relates to their:

– sex

– marital or relationship status

– actual or potential pregnancy

– sexual orientation

– gender identity

– intersex status.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 20

FOIREQ24/00508 0206

Pronoun choice

Learn the user’s preferred pronoun. If it’s not clear and you can’t ask them, choose gender-neutral

pronouns.

The singular ‘they’ is gender-neutral. It avoids specifying a person’s gender.

You can use ‘they’ or ‘them’ when you would otherwise use a singular personal pronoun such as:

• ‘he’

• ‘she’

• ‘him’

• ‘her’.

You can also use ‘themselves’ or ‘themself’ instead of ‘himself’ or ‘herself’. ‘Themself’ is an

extension of using ‘they’ for a single person.

The use of gender-neutral pronouns to refer to a person of unknown gender has a long history.

Usage now covers people who either:

• don’t wish to identify as a particular gender

• identify as non-binary or gender-fluid.

There are many ways to avoid using gender-specific pronouns.

You must provide copies of the application to your referees. [Use the second-person

pronouns (‘you’ and ‘your’) with direct tone and active voice.]

Candidates must provide copies of the application to their referees. [Use a plural pronoun.

The pronoun ‘their’ relates to a plural subject ‘candidates’.]

Every candidate must provide copies of the application to referees. [Leave the pronoun out

altogether.]

Avoid gender-specific job titles

Avoid using job titles that end in ‘-man’ or ‘-woman’.

Avoid using the traditional terms for jobs that end in ‘-man’ e.g. policeman, foreman.

You should also avoid job terms that specify women e.g. actress, waitress.

The digital Style Manual contains new guidance on inclusive language around gender and

sexual diversity. It adds advice on the distinctions between gender, sex and sexuality, on

LGBTIQ+ communities and on the use of the title ‘Mx’.

See the digital Style Manual: Gender and sexual diversity

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 21

FOIREQ24/00508 0207

People with disability

Disability does not define people. Use inclusive language that respects diversity.

Focus on the person, not the disability

Mention disability only when it’s relevant to the content.

When you are writing about people with disability, focus on the person. Use person-first language

for Australian Government content.

people with disability [Person-first language]

disabled person [Identity-first language]

Be responsive if you get feedback on the language you’ve used. It can guide user research around

language that respects individual or community preferences.

Use respectful and inclusive language that talks to the person – not their difference.

Commonwealth laws include:

–

Disability Discrimination Act 1992

–

Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 22

FOIREQ24/00508 0209

Structure your content by writing about one idea at a time. When you write:

• start with the most important idea first

• group related ideas under headings

• organise ideas into short paragraphs.

Headings

Headings help users scan content and find what they need. Organise content using clear

heading levels. Begin each heading with keywords and keep it to the point.

Write headings that are clear and short

Headings organise information. Clear headings are specific to the topic they describe.

Keep them brief. They are signposts for people and for search engines.

Many people skim through headings to check whether a page is relevant before they read it in

detail. Search engines use headings to analyse and rank content.

State the main point

Write headings that tell the user what is in the content below it. Headings should state the main

point. This helps users find content in search results.

Write this

Learn how to drive

Not this

More information

Use fewer than 70 characters

Write headings that are no more than 70 characters (including spaces).

Longer headings are more difficult to read and can be confusing. They might also suggest that you

have too many ideas in a section.

Avoid questions as headings

Starting a heading with ‘why’, ‘how’ or ‘what’ makes it slower for the user to read. They have to

read the whole heading before finding relevant keywords.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 24

FOIREQ24/00508 0210

Use keywords to start headings

Start headings and subheadings with keywords that help people to make a connection.

People scan-read headings to know the relevance of the content. If they use assistive

technologies, they might use the tab key to read from heading to heading. Others who use screen

readers might generate a list of headings for quick navigation.

The keywords should relate to the main content below the heading. Pay special attention to the

first 2 or 3 words. These might be the only words someone reads to decide whether to continue to

scan the page or to read the text.

Using keywords at the start of a heading is called ‘frontloading’. Frontloading makes it easier for

people to assess the heading’s relevance – either on a webpage or in search results. It also helps

search engines find your content.

Be consistent: use a parallel structure

All headings in a level should be consistent.

They should have the same:

• overall message (for example, they are all steps in a process)

• grammatical form (called ‘parallel structure’).

Two common forms are:

• noun phrases (for example, ‘effective headings’ and ‘punctuation and capitalisation’)

• instructions (for example, ‘keep headings short’ and ‘be consistent’).

Write all headings in sentence case and use minimal

punctuation

Use sentence case for headings to help people read the text more easily.

This means you should use a capital letter only for:

• the first letter of the first word

• the first letter of any proper nouns

• letters in acronyms and initialisms.

Don’t use a full stop to end headings

Even if the heading is a sentence, it doesn’t need a full stop at the end.

Avoid using shortened forms in headings

Don’t use a shortened form in a heading unless it is better known than the ful term (for example,

‘DNA’ and ‘CSIRO’).

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 25

FOIREQ24/00508 0211

Links

Links can help users navigate content. Include links when they support user journeys. Write

link text that is accurate and accessible.

Link to HTML content by default – only link to a file (e.g. a PDF) if an HTML version is not

available. Always provide the document title, file type and file size (where possible).

Link to HTML content whenever possible

Provide content in HTML format by default. This has benefits for both accessibility and

maintenance. If a full HTML version of the file is not available, link to a summary page if it exists.

When linking to files, include document title, file type and size

There will be some situations in which you need to link to non-HTML documents and files. Give

users the information they need to decide whether to download the file by providing the:

• document title (not the file name)

• the file type

• the file size in kilobytes (kB) or megabytes (MB) (where possible).

Include all this information in the link text, but remember that this adds extra information for all

users. Minimise the number of links where you can.

Write link text that makes the destination clear

Users scan content for links to understand what it is about. People who use assistive technologies

often use the tab key to read from link to link. People who use screen readers often generate a list

of links for quick navigation.

For these reasons, links need to make sense when read out of the context of surrounding content.

Links like ‘click here’ or ‘more information’ don’t give the user any information about the

destination.

Write link text that describes the destination in clear language. Match the content on the linked

page so the user knows they have reached the right place.

Write this

Find out about our upcoming meetings on our

Eventbrite page.

Not this

Click here to find out about our upcoming meetings.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 26

FOIREQ24/00508 0212

Lists

Lists make it easy for users to scan and understand a series of items. Structure and style

lists with the user in mind. Set up grammatical structure for list items with a lead-in.

Structure items in a series as a list

Lists are series of items. All lists have a phrase (lead-in) or heading to introduce the list.

Use lists to:

• help users skim information

• group related information

• help users understand how items relate to each other

• show an order of steps

• arrange information by importance.

Lists can be ordered or numbered (the order is important) or unordered (the order is not critical).

Make short lists

Long lists can lose meaning and hierarchy, as lower items are further away from the lead-in.

Move long lists to a separate page or an appendix.

Limit the number of lists

Content with too many lists is hard to follow. The content should flow so people can read it easily.

Use a consistent pattern for list items

Write items in a list so they follow a consistent pattern. The pattern is made up by the number of

words you use and grammatical structure.

If items follow a consistent pattern, it makes a list easier to scan and understand.

Write list items so they have parallel structure

Write all list items so they have the same grammatical structure. This is called ‘parallel structure’.

It makes lists easier to read. To make a parallel structure, use the same:

• word type to start each item (such as a noun or a verb)

• tense for each item (past, present or future)

• sentence type (such as a question, direction or statement).

Move any words repeated in the list items to the lead-in.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 27

FOIREQ24/00508 0213

Write this

Not this

I will:

I will be:

read more emails

reading more emails

go to meetings

going to meetings

be punctual.

punctual

[The last item is an adjective while other list items begin with verbs.]

Punctuate lists according to style

Unnecessary punctuation makes your list look cluttered. Current government style is for minimal

punctuation.

Use minimal punctuation for all lists

In a bullet or numbered list, don’t use:

• semicolons or commas at the end of list items

• ‘and’ or ‘or’ after list items.

Only include ‘and’ or ‘or’ after the second-last list item if it is critical to meaning – for example, you

are writing in a legal context. Make sure the lead-in is a clear guide for how this kind of list should

be interpreted.

Lead-ins for incomplete lists can use ‘for example’, ‘including’ or ‘includes’.

Don’t write ‘etc.’ at the end of the list to show the list is incomplete.

When listing items that may be additional or optional, write a lead-in to explain any variables.

Use full stops to complete sentences and fragment lists

Sentence lists and fragment lists are 2 types of list that use full stops.

• Finish each item in a sentence list with a full stop, including the last one.

• Finish fragment lists with a full stop only after the last item.

If you don’t include the full stop, people using screen readers may assume the next paragraph is

part of the list.

A stand-alone list is a third type of list. If you are not breaking up a paragraph or a sentence,

consider a stand-alone list. Stand-alone lists use a heading, not a lead-in. Start each item

with a capital letter. Don’t add full stops to the end of any items (even the last item).

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 28

FOIREQ24/00508 0214

Avoid using a multilevel list

Multilevel lists group information into a hierarchy. The levels explain how each item relates to

other list items.

If you have to use multilevel lists:

• don’t use more than 2 levels

• use lowercase letters for the second level in a numbered list

• use a dash for the second level in a bullet list, not hollow (open) bullets

• use the same symbol, number or letter for the same level in each list.

Paragraphs

One idea per paragraph helps users absorb information. Organise them under headings to

help users scan the content. Write short paragraphs, each with a topic sentence.

Limit each paragraph to one idea

People find it easier to understand content when a paragraph contains only one idea or theme.

Don’t introduce a new idea in the middle or at the end of a paragraph. Start a new paragraph

instead.

Introduction or summary paragraphs recap ideas covered in the content. Group sentences in these

paragraphs by theme – for example, to help users understand how the content is structured.

Keep most paragraphs to 2 or 3 sentences

Short paragraphs help people understand content. The ideal length depends on what you are

writing.

• Media releases and news articles have only one or 2 sentences in a paragraph.

• Content designed for mobile screens has no more than 2 or 3 sentences in a paragraph.

• In reports and other long-form content, a limit of 6 sentences in a paragraph is acceptable.

If your paragraphs or sentences are too long, you might be trying to say too much in one place.

Consider starting a new paragraph or using an itemised list. Make sure the items relate to each

other and are grammatically parallel.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 29

FOIREQ24/00508 0216

Italicise titles of stand-alone works, legal cases and Acts

A title or name in italic type shows that it is formal and complete. Shortened versions of the title

and common titles are in roman type. Follow the detailed Style Manual guidance for referencing

and attribution.

Published works

Use italics for the titles of these published works:

• books and periodicals

• plays

• classics

• most musical compositions

• ballets and operas

• films, videos and podcasts

• blogs

• television and radio programs

• artworks.

Unpublished works are in roman type.

Full titles of Acts and legal cases

Use italics for primary legislation and legal cases but not for delegated legislation or bills.

See Legal material

Set off most foreign words and phrases

Italics contrast words and phrases that are not in English from surrounding text. Foreign words

and phrases should generally be avoided in government writing, unless there is no English

equivalent.

Standard Australian English can absorb words or phrases from other languages. Write these

‘borrowed’ words without italics or accent marks.

Stress words with special emphasis, but rarely

Sometimes you want to stress a word for meaning or to convey emotion, including a change in

tone. Italics, used sparingly, can work for this purpose.

Don’t use italics when another style or formatting option is available. Single quotation marks can

work for emphasis unless they’re serving a different stylistic use.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 31

FOIREQ24/00508 0217

Emphasis in quotations

Sometimes, you might want to add italics to quotations to bring attention to particular words or

phrases. If you do this, write ‘emphasis added’ in square brackets following the italicised text.

Punctuation and capitalisation

Punctuation and capitalisation have rules for correct use. Use minimal punctuation and

capitalisation to make content more readable.

Include a single space after a full stop. Never use double spaces.

Use minimal punctuation to make meaning clear

Minimal punctuation doesn’t mean removing all punctuation marks from a sentence. It means

removing unnecessary punctuation.

Only use punctuation that makes the sentence grammatically correct and the meaning clear.

Too much punctuation makes text crowded and difficult to read. If a sentence has a lot of

punctuation marks, it might be a sign that the sentence is too long or complex. Try to rewrite into

shorter, clearer sentences.

To use minimal punctuation:

• don’t add full stops to the ends of headings, page headers, footers or captions

• don’t use a semicolon at the end of each item in a bullet list

• unless each item is a full sentence or the last item in a list, don’t use a full stop for items in

bullet lists

• don’t use full stops between letters in an acronym or initialism

• don’t use a full stop at the end of most abbreviations.

Minimal punctuation helps all users to understand content.

Use the correct spacing around punctuation marks

There are different rules for putting spaces around punctuation marks. For example, some

punctuation marks have no spaces around them. Some have a space on either side.

Include a single space after a punctuation mark at the end of a sentence (full stop, exclamation

mark or question mark).

Never use double spaces. Check each document for double and multiple spaces and delete them.

Minimise capitals for common nouns and adjectives

Proper nouns generally have an initial capital letter for each word in the noun.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 32

FOIREQ24/00508 0218

Common nouns and adjectives don’t use initial capitals, with few exceptions. For example,

adjectives often have capitals when they refer to a national, religious or linguistic group.

Follow the guidance on capitals for titles and government

terms

Follow the conventions for using capitals in this Style Guide.

See Titles, honours, forms of address

See Government terms

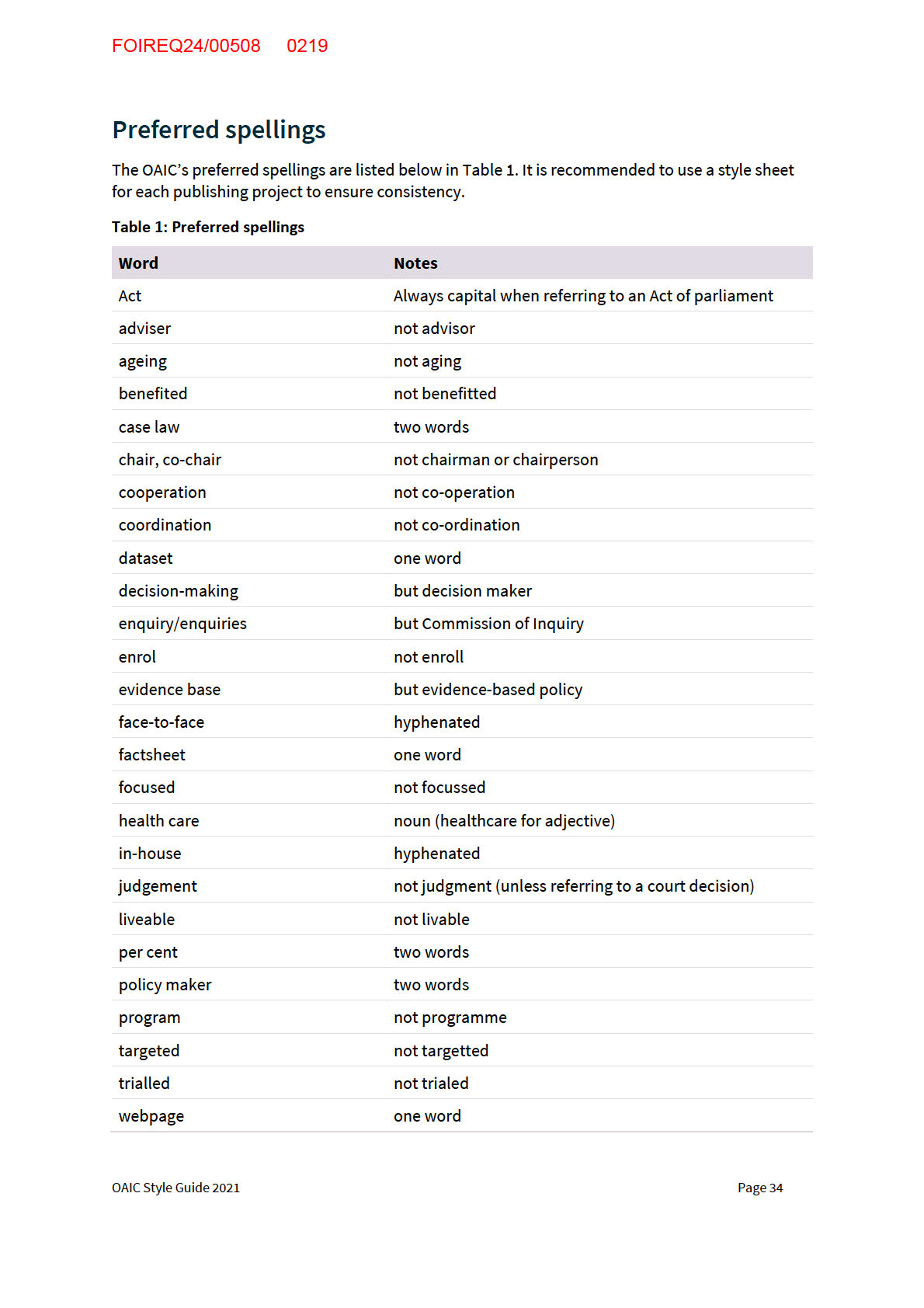

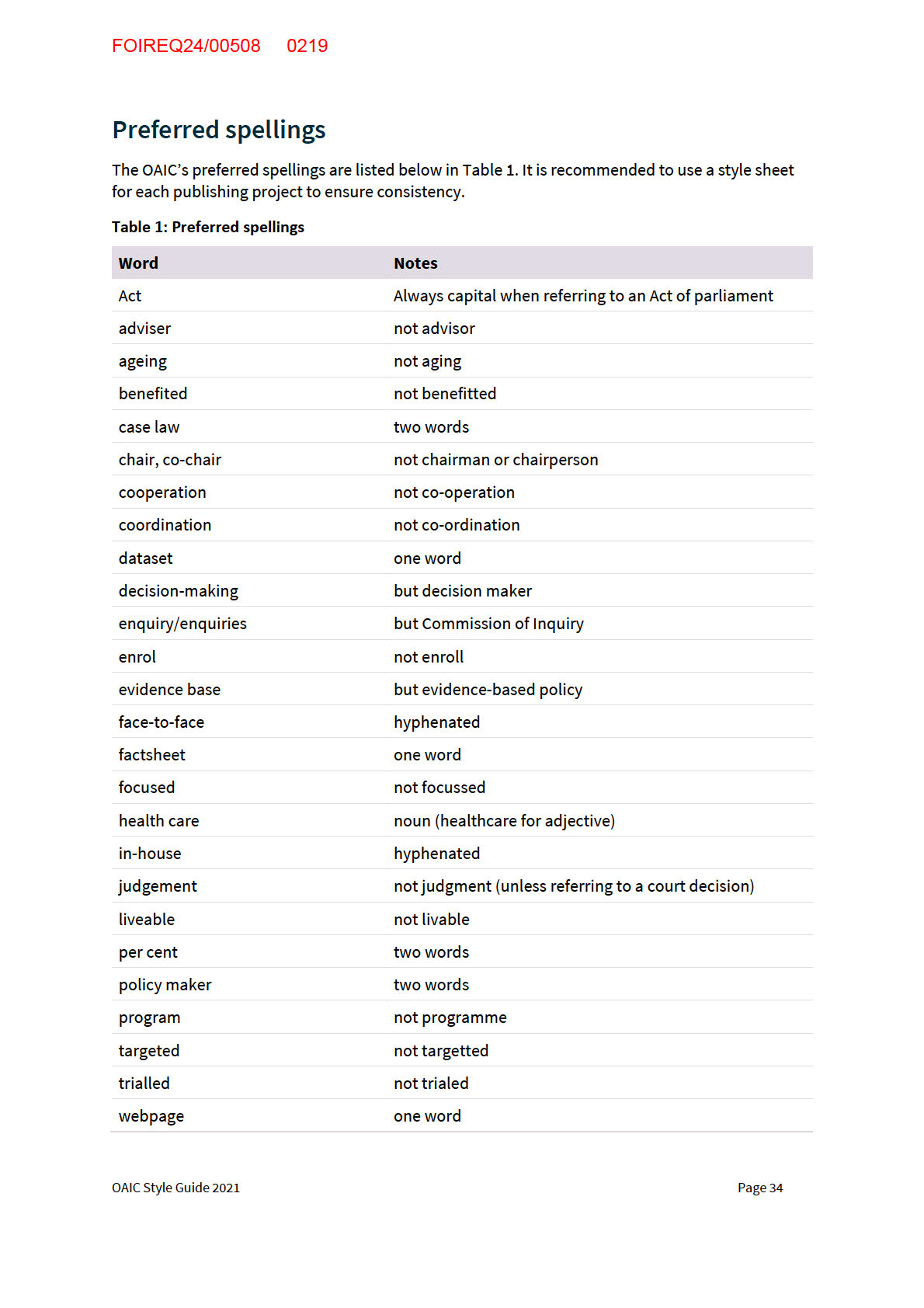

Spelling

Spelling errors detract from readability. Follow one dictionary for consistency and to check

variable spellings.

Macquarie Dictionary

The OAIC follows

Macquarie Dictionary spelling.

You should be automatically logged into the

Macquarie Dictionary when you are working in

the office.

To log in at home go to macquariedictionary.com.au and enter the following:

Username:

OAIC

Password:

OAIC1234

The Australian Government standard is to use Australian English spelling and not American

spelling. The only time you should use a ‘z’ instead of an ‘s’ is for a proper noun e.g. World Health

Organization.

The exception to this rule is quoted material, when you should use the spelling in the published

original.

Australian English in Microsoft Word

To prevent Microsoft Word from Americanising your spelling and converting ‘s’ to ‘z’ go to

the Review tab, click on Language and then Set Proofing Language. Select English

(Australia) and click on Set As Default. OAIC templates are set to default to Australian

English spelling. See Appendix C: OAIC templates.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 33

FOIREQ24/00508 0221

Shortened names for states and territories (by population size)

NSW

Vic

Qld

WA

SA

Tas

ACT

NT

Government terms

Use the correct term and follow the rules for capitalising government terms. People find it

easier to understand content that has a consistent style.

Use initial capitals for formal names and titles

Use initial capitals only for the formal names and titles of government entities and office holders.

Use lower case for generic references.

There are some exceptions to this rule:

• Budget (unless you are using it as an adjective or as a plural)

• Cabinet

• Commonwealth

• Crown

• Treasury.

Australian Government

Refer to the national government of Australia as the ‘Australian Government’. Use an initial capital

for both words only when they occur together.

Always use Australian Government. Do not use Commonwealth Government or Federal

Government.

Departments and agencies

Use initial capital letters only for the formal names of government departments and agencies.

Check the names of departments and agencies in the government online directory.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 36

FOIREQ24/00508 0222

Don’t use capital letters for generic mentions. For example, use:

• ‘the agency’ instead of ‘the Agency’

• ‘the commission’ instead of ‘the Commission’

• ‘the department’ instead of ‘the Department’.

Use a shortened form of the name only if the department or agency uses it regularly in their own

content.

If you cite a source written by an organisation that has since changed its name, use the name

published in the source. This might not be the organisation’s current name.

The Flipchart of Commonwealth entities and companies (PDF) is a handy 2-page reference

guide, organised by portfolio, that lists departments and agencies with links to the relevant

websites.

The List of Commonwealth entities and companies (PDF) is a 30-page document, organised

by portfolio, which provides ABNs, enabling legislation and other governance-related

details for departments and agencies, as well as links.

The Department of Finance produces the flipchart and list and the dates reflect when the

documents were updated, not when the change occurred.

More information about government bodies can be found at Types of Australian

Government bodies and Australian Government Organisations Register.

Government programs and agreements

Use initial capitals for the full names of:

• government programs

• treaties

• protocols and similar agreements.

National Aged Care Advocacy Program

Legislation

Use initial capitals for these terms when referring to specific legislation:

• Act

• Ordinance

• Regulation

• Bill.

Use lower case for generic references to bills, regulations and ordinances.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 37

FOIREQ24/00508 0223

Use initial capitals for all references to Acts.

Use government sources to check the titles of legislation, especially:

– the Federal Register of Legislation

– the Australian Parliament House list of bills and legislation.

See Legal material

See Delegated legislation

Commercial terms

Brands and model names are protected by law. Unless using common names, write trade

mark names and use symbols so people can understand legal status.

For guidance see the digital Style Manual:

Use initial capitals for commercial terms

Use a common word for a product if you can

Take care using product names

Dates and time

Dates and times need to be readable. Write, abbreviate and punctuate dates and times

consistently so people can understand your content.

Follow Australian conventions for dates

Australian style conventions apply to dates expressed in numerals and words, and in numeric

formats.

Months and days

Months and days are proper nouns, so they start with an initial capital.

Use abbreviations only if space is limited, for example, in tables, illustrations, charts and notes.

Ensure it is obvious to users which months or days you are referring to.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 38

FOIREQ24/00508 0224

The standard abbreviations for the days of the week are:

Monday – ‘Mon’ or ‘M’

Tuesday – ‘Tues’ or ‘Tu’

Wednesday – ‘Wed’ or ‘W’

Thursday – 'Thurs’ or ‘Th’

Friday – ‘Fri’ or ‘F’

Saturday – ‘Sat’ or ‘Sa’

Sunday – ‘Sun’ or ‘Su’.

The standard abbreviations for the months are:

January – ‘Jan’

February – ‘Feb’

March – ‘Mar’

April – ‘Apr’

May – retain as ‘May’

June – retain as ‘June’ or shorten to ‘Jun’

July – retain as ‘July’ or shorten to ‘Jul’

August – ‘Aug’

September – ‘Sept’

October – ‘Oct’

November – ‘Nov’

December – ‘Dec’.

Full dates

In general, use numerals for the day and the year but spell out the month in words. Don’t include a

comma or any other punctuation. When using full dates, don’t use ordinal numbers.

Write this

Friday 1 May 1997

Not this

May 1, 1997

Friday, 1 May 1997

1st May 1997

Use ‘from’ and ‘to’ in spans of years

Avoid en dashes in spans of years. Write the years out in full.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 39

FOIREQ24/00508 0225

from 2015 to 2019

The exceptions are:

• financial years

• information in parentheses, such as terms of office and years of birth and death.

For these, use an en dash without any spaces on either side.

the 2020–21 financial year

Sidney Nolan (1917–1992) had 3 younger siblings.

Don’t use an apostrophe for decades

Write the span of decades with an ‘s’ on the end. Do not use an apostrophe.

2010s not 2010’s

1980s not 1980’s

Use numbers for the time of day when you need to be precise

In most documents, especially when you need to be precise, numbers give a clearer expression of

time.

Use a colon between the hours and minutes. The use of a colon as the separator reflects a shift in

contemporary Australian usage and avoids confusion with decimal numbers.

The bus leaves at 8:22am.

Write ‘o’clock’ only when quoting someone directly or transcribing a recording. Use numerals and

the word ‘o’clock’.

‘The minister is speaking at about 10 o’clock,’ they said.

Times using ‘am’ and ‘pm’

Use ‘am’ and ‘pm’ in lower case. You can use 2 zeros to show the full hour, but they aren’t

essential.

9am or 9:00am

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 40

FOIREQ24/00508 0226

Noon, midday and midnight

Use ‘noon’, ‘midday’ or ‘midnight’ instead of ‘12am’ or ‘12pm’ to make it easier for people using

your content to be certain of the time.

Time zones

You might also need to define which time zone you are referring to.

The Australian zones are:

CST (Central Standard Time)

CDT (Central Daylight-saving Time)

EST (Eastern Standard Time)

EDT (Eastern Daylight-saving Time)

WST (Western Standard Time).

We generally add an ‘A’ (to represent ‘Australian’) to the front to avoid confusion.

10:30am AEST

Organisation names

Spell and punctuate organisation names correctly. This helps people to understand your

content.

Write the name as the organisation writes it

Organisations determine how their names should be spelt and punctuated. This does not always

follow the usual rules.

Write the name of the organisation the same way the organisation writes it. This rule applies

except in rare cases when the organisation name is in all lower case. Use an initial capital for these

names in general text. This helps people identify the name as a proper noun.

Some names start with a lower case letter but have a medial capital (for example, ‘eBay’). Write

the name the same way, including to begin a sentence. A medial capital is enough to identify the

name as a proper noun.

eSafety keeps tips on its website topical and up to date.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 41

FOIREQ24/00508 0227

Pay attention to the use of capital letters, punctuation (such as apostrophes) and logograms (such

as ‘&’). Make sure to include all words in the name. Don’t add additional words.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [Note the lack of

apostrophe for ‘Nations’ and the variant spelling of ‘Organization’.]

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) [The ampersand is part of the

initialism but not the spelt-out form.]

State Library Victoria [The name is not the ‘State Library of Victoria’. It does not include a

preposition.]

Meat & Livestock Australia [The ampersand is part of the name.]

Check the correct name of an organisation

The names of organisations can change. The most efficient way to confirm an organisation’s name

is to check its website, annual report or letterhead.

• For Australian Government entities, use the government online directory. It includes the

Australian Government organisations register and the directories of state and territory

governments. There are also website directories for some local governments.

• Name searches are useful for company and business names, especially the ABN

lookup, Australian Securities and Investments Commission registers and the Australian

Securities Exchange’s listed companies.

If you cite a source written by an organisation that has since changed its name, use the name that

was published in the source. This may be the organisation’s past name.

Before September 2013, the Department of Social Services was called the ‘Department of

Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs’.

Shortened forms of the name

Use the organisation’s shortened form only if the organisation regularly uses it in its own content.

For example, the Department of Home Affairs uses ‘Home Affairs’ as the shortened form. It would

be inappropriate to use ‘DHA’ to refer to Home Affairs. However, Defence Housing Australia does

use the initialism ‘DHA’, so using it to refer to that organisation would be appropriate.

Spell out the shortened form the first time, unless the organisation’s name is known only by the

shortened form.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 42

FOIREQ24/00508 0228

In general text, use lower case for the definite article in the names of

organisations

Some organisations use the definite article ‘The’ in their name with an initial capital. Use the full

name, including ‘The’, in 2 situations:

• letters

• if the name appears in an alphabetical list (arrange by ‘The’ as the first word in the name)

Always use lower case ‘the’ in general text. This follows the practice of most organisations.

The University of Sydney [Correct name, not ‘University of Sydney’]

Next year the University of Sydney will renovate its science buildings. [General text uses

lower case for ‘the’]

Put a possessive apostrophe in a name if the organisation

does

Use an apostrophe only when it forms part of the official name of an organisation.

Actors’ and Entertainers’ Benevolent Fund Qld

In all other cases for organisation names, don’t use possessive apostrophes.

The apostrophe is disappearing from many organisational names, particularly from those that

contain plural nouns ending in ‘s’. In these cases, the plural noun is descriptive rather than

possessive.

Australian Securities and Investments Commission

Minerals Council of Australia

Australian Workers Union

We do not use possessive apostrophes for the names of our OAIC networks.

Information Contact Officers Network (Officers is descriptive)

Privacy Professionals Network (Professionals is descriptive)

Use the singular verb with organisation names

In formal writing we use a singular verb with organisation names. On our website and in social

media, ‘they’ is acceptable for an organisation or agency.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 43

FOIREQ24/00508 0230

Write all numbers as numerals in these specific situations

There are exceptions to using words for ‘zero’ and ‘one’.

Write all numbers as numerals:

• in units of measurement

• to show mathematical relationships – such as equations and ratios – and for decimals

• when you are comparing numbers

• in tables and charts

• for dates and times

• in a series of numbers

• in specific contexts – such as steps, instructions, age and school years

• in scientific content.

Date and times

Always use numerals for date and times. Use a colon between the hours and minutes.

Series of numbers

In any document that contains a lot of numbers, it is always better to write numbers as numerals.

Always use numerals for:

• a related group of items

• a discussion of statistics.

This is regardless of the size of the numbers involved.

The anthology includes 160 poems by 22 poets – 14 of whom were born in Australia, 4 in

New Zealand, 3 in England and 1 in Austria.

If you have 2 series of numbers, for the sake of clarity you can use words for one series and

numerals for the other.

Of the mothers of the 23 sets of triplets registered during the year, 8 had no previous

children, 8 had one child and 7 had two previous children.

Choose between numerals or words for currency

Use numerals and symbols for amounts of money.

However, money can be written entirely in words for approximations and figures of speech.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 45

FOIREQ24/00508 0231

Combine numerals and words for large rounded numbers

Numbers up to one million are easy to read as numerals. When you’re using rounded numbers of

1,000 or more, use commas to separate numerals into groups of 3 (working right to left).

Use a combination of numerals and words for large numbers over a million when they are

rounded. It is easier to read ‘2.5 million’ than ‘2,500,000’.

The budget allocated $50 billion to that initiative.

The organisation announced $3 trillion in superannuation savings.

Currency

Use the correct numbers, words and symbols for currency so people are clear about the

amount.

For guidance see the digital Style Manual:

Quantify an amount of money with a symbol and numeral

Clarify when you are using Australian dollars

Reference non-Australian currencies for accessibility

Quantify large amounts of money

Use words for inexact amounts

Measurements and units

Standard units of measurement support readability and accuracy. Express precise values

for users by combining numerals with the correct unit symbol.

For guidance see the digital Style Manual:

Use the standard units of measurement

Write numerals with units of measurement

Use symbols for common units of measurement

Put a non-breaking space between numbers and units

Don’t add ‘s’ for plural forms

Compare measurements using the same units

Only use non-SI units if the user understands them

Avoid imperial units

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 46

FOIREQ24/00508 0232

Ordinal numbers

Ordinal numbers such as first, second and third show the order and importance of things.

With large ordinals, spell out the number and include the suffix, for example, the millionth

visitor.

Avoid using ordinals to order points in general text. Reword the content or use a numbered

list instead. A list is easier for people to follow.

Exclude ordinals in dates, use plain numerals, for example, 12 February 2005.

Sort and compare the order of things using ordinals

Ordinal numbers show the order or position of something in a sequence.

Ordinals always have a suffix:

‘-st’ (‘first’, ‘21st’)

‘-nd’ (‘second’, ‘32nd’)

‘-rd’ (‘third’, ‘103rd’)

‘-th’ (‘fourth’, ‘15th’, ‘55th’ and so on).

Ordinal numbers to ‘ninth’

Write ordinal numbers up to ‘ninth’ in words.

the third example

the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month

Percentages

Percentages help people compare things and understand proportions. Use numerals with

the percentage sign. Be concise when you write about percentages.

Use numerals with the percentage sign

Use the percentage sign next to a numeral in text. Don’t use a space between the number and the

percentage sign.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 47

FOIREQ24/00508 0233

15%

Use decimals rather than fractions with the percentage sign.

Write

The price of Tapis oil is up by 0.25%.

Not

The price of Tapis oil is up by ¼%.

Avoid starting a sentence with the percentage. Reword the sentence if possible, or write the

percentage out in words. You can use everyday words if a precise amount is not needed.

Use the correct form of the noun (percentage)

‘Per cent’ and ‘percentage’ aren’t the same. The term ‘per cent’ is an adverb. The noun form is

‘percentage’.

Statistics show the percentage of Australians with university degrees is increasing.

‘Per cent’ is written as 2 words in Australia. ‘Percent’ is not Australian spelling.

Don’t use percentages to describe change

Avoid using percentages to describe changes.

Tell people what the actual increase or decrease is.

Like this

The application fee is now $70. This is a $20 increase from 1 January 2020.

Not this

The application fee increased by 40% from $50 to $70 on 1 January 2020.

Be concise when writing about percentages

When you use many percentages in running text, put the figures in brackets (parentheses) or use a

list to simplify the text.

In 2019, population size increased in New South Wales (32%), Queensland (20%) and

Victoria (19%).

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 48

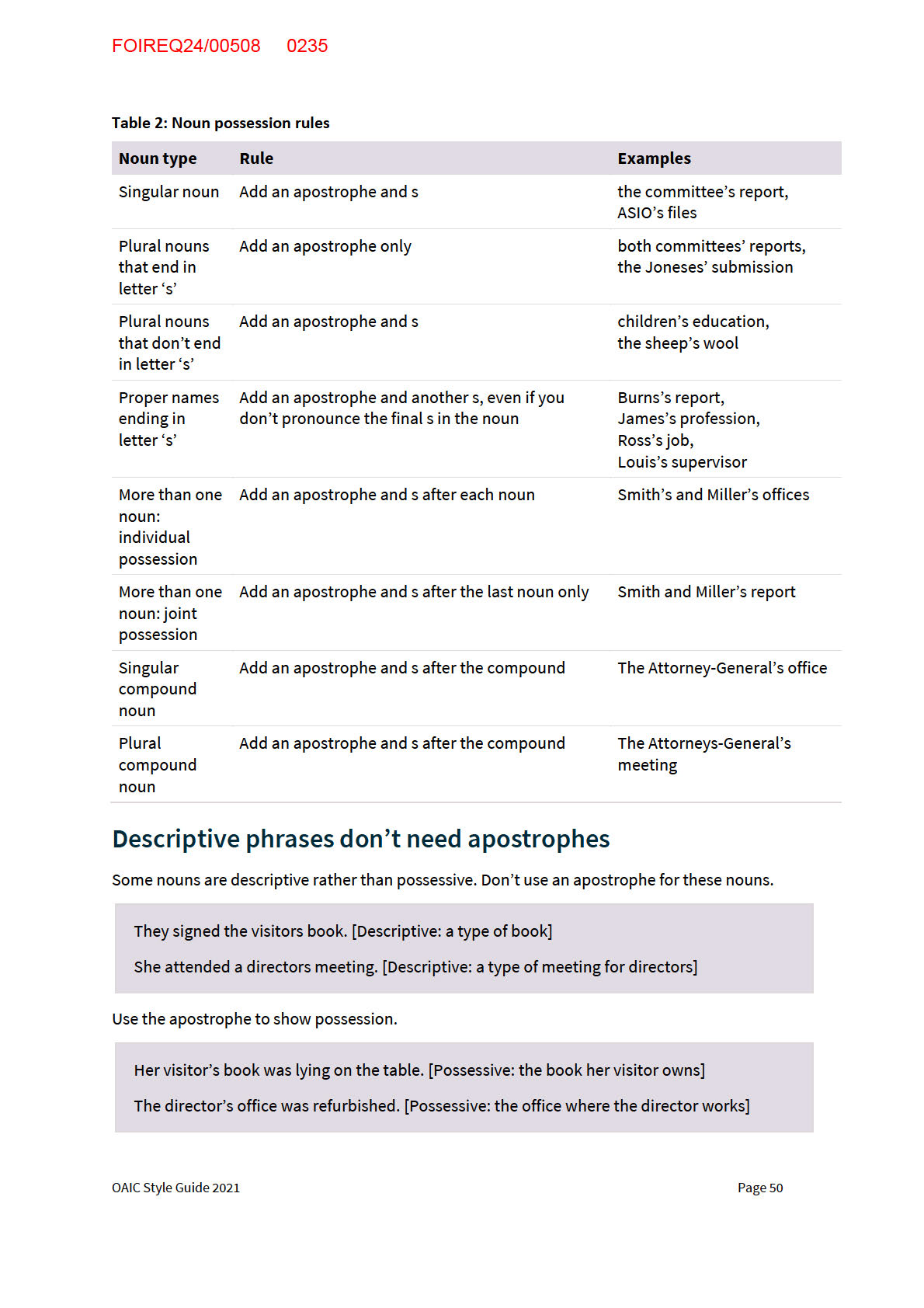

FOIREQ24/00508 0236

Noun phrases about time don’t need apostrophes because they’re descriptive, not possessive.

6 weeks time

3 months wages

When the time reference is in the singular, use an apostrophe to show the noun is singular.

a day’s work

the year’s cycle

Apostrophes show contractions

Apostrophes show that you have omitted letters in contractions.

I haven’t seen the report.

It’s a busy day at the office.

Don’t confuse ‘it’s’ (the contraction of ‘it is’ or ‘it has’) with ‘its’ (to show that ‘it’ owns

something).

If you can divide ‘it’s’ into ‘it is’ or ‘it has’, then you need to use an apostrophe. ‘Its’ is a

possessive pronoun and doesn’t have an apostrophe.

It’s time to give the committee its terms of reference.

Plural nouns don’t have apostrophes

No apostrophe is needed for the plural form of a noun. This type of error is known as the

‘greengrocer’s apostrophe’.

25 million Australians

the 2020s

committee reports

fresh avocados

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 51

FOIREQ24/00508 0237

Brackets and parentheses

Brackets can make it easier for the user to scan text. Use brackets when it would not change

the meaning if you removed enclosed text.

Avoid using square brackets inside parentheses.

Don’t use sets of parentheses inside each other. Instead, use square brackets if you must

put parenthetical information within parentheses.

Use square brackets to show insertions in quotes.

Use brackets for text users can skip over

Brackets can help you break up information. They enclose parts of the sentence that aren’t

essential to the meaning. Sentences must be grammatically correct if you remove the text in

brackets.

The most commonly used brackets are:

• parentheses

• square brackets.

Use brackets sparingly for:

• non-essential information

• shortened forms

• references

• insertions.

Use brackets only where they make content clearer to people. For example, always use brackets in

author–date citations.

Too many brackets, or badly used brackets, can make a sentence more complex and difficult to

understand. You can usually rewrite a sentence so the content in brackets can be its own sentence

or can even be removed.

Put extra information in parentheses

Information in parentheses is less important than information that is between spaced en dashes

or pairs of commas. Used well, parentheses can improve meaning and make content easy to scan.

Definitions

Parentheses enclose definitions.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 52

FOIREQ24/00508 0238

Medicare (Australia’s universal health insurance scheme) guarantees all Australians access

to a wide range of health and hospital services.

Shortened forms

Parentheses introduce a shortened form after it has been spelt out in full. You can then use the

shortened form through the rest of the page or publication.

The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) is responsible for research

funding and health guidelines.

Cross-references

Parentheses enclose cross-references to other parts of the content.

Australia’s population increased by 350,000 people last year (Table 1).

Citations

Parentheses enclose citations in the author–date system of referencing.

China is Australia’s largest trading partner (Smith 2019).

Extra detail

Parentheses enclose extra detail.

Our 2 biggest exports are iron ore ($61.4 billion) and coal ($60.4 billion).

The winning tenderer (which was a local company) signed the contract on Tuesday.

Clarification and asides

Parentheses enclose text that doesn’t have a grammatical relationship to the rest of the sentence.

This type of text includes extra information, clarifications and asides.

The department was in a heritage-listed building. (The building was designed by award-

winning architect Enrico Taglietti.)

Whitlam’s comments on the steps of Parliament House (‘Well may we say .. ’) are still widely

quoted.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 53

FOIREQ24/00508 0239

Write brackets in the same type as the surrounding text

Brackets should be in the same type (roman, italics, bold) as the text around the brackets. This is

regardless of the type of the text inside the brackets.

This is the same rule as for quotation marks.

The most recent review of defence policy (2016 Defence white paper) set the direction for

the next 10 years. [In this example, the parentheses are not in italics because the

surrounding text is not in italics.]

Colons

A colon draws the user’s attention to text that follows. Add colons only if essential.

Use them to introduce lists and block quotes. Use a colon for time, for example, 10:00am.

Limit colon use

Use a colon only if you are sure it is needed. Incorrect use creates confusion for users.

Introduce examples and contrasts with colons

Use a colon to:

• introduce a word, phrase or clause that provides more detail

• introduce a question

• give an example

• summarise or contrast with what comes before it.

Use correct spelling: check a dictionary if you need to.

Our work is about answering this simple question: how?

We’ll have to use a stronger tool: sanctions.

This is the guiding principle for our workplace: collaboration.

Start lists with a colon

Use a colon to introduce a list of words, phrases or clauses.

Pick any 2 of the 3: low price, high speed, high quality.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 54

FOIREQ24/00508 0240

We need to:

• check Appendix A of the report

• ask Mary about the final chapter of her book

• rewrite our introduction.

Commas

Commas separate parts of a sentence so meaning is clear to users. Sentence structure

determines correct use.

Separate introductory words, phrases and clauses with a

comma

A comma separates introductory words, phrases and clauses from the main clause of the

sentence.

Many introductory phrases can be moved to the end of sentences without changing the meaning.

In these cases, you don’t need a comma before the phrase. This simpler structure can be easier to

read.

During the meeting, we discussed Item 9.

We discussed Item 9 during the meeting.

Place a comma after adverbs and other introductory words

Use a comma after introductory words, such as greetings and adverbs, or when addressing

someone. Using an introductory word gives it emphasis.

Yes, they went to the estimates hearing. [Affirmative emphasis]

Goodnight, and good luck. [Greeting]

Actually, that's an interesting point. [Adverb]

Excuse me, should I come with you? [Addressing someone]

You don’t need a comma after an introductory word if the sentence is very short. This minimises

punctuation in very short sentences.

Today I went to work.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 55

FOIREQ24/00508 0241

Use a comma after phrases and clauses that change the whole sentence

Use commas after adverbial phrases and adverbial clauses. Adverbs – such as ‘first’ and ‘during’ –

modify verbs, adjectives and other adverbs.

During the meeting, we discussed item 9. [Adverbial phrase]

Although they were shaking and sweating, the firefighters were relieved to feel the first

drops of a downpour. [Adverbial clause]

Conditional clauses are adverbial clauses (for example, beginning with ‘if’, ‘unless’ or ‘until’). They

should also have a comma after them if they start the sentence.

Unless the consultation starts early, it will not finish on time. [A conditional adverbial

clause]

Avoid beginning a sentence with a string of numbers and dates

Use a comma after an introductory phrase that ends with a numeral and is immediately followed

by another numeral. It doesn’t matter how short the sentence is.

Avoid this type of sentence structure because the string of numbers can be confusing.

Write this

There were 16.5 million people enrolled to vote in Australian elections on 18 April 2019.

Not this

On 18 April 2019, 16.5 million people were enrolled to vote in Australian elections.

Mark out non‐

essential information within a sentence

Commas isolate information in a sentence when it isn’t essential to:

• meaning

• grammatical structure.

Within a sentence, use a pair of commas to separate non-essential or supplementary information.

Always check for the second comma where there should be a pair.

Generally, if you can take out part of the sentence and it is stil grammatically correct, it should be

between a pair of commas.

Check carefully. Using comma pairs can completely change the meaning of a sentence.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 56

FOIREQ24/00508 0242

Elements that function as supplementary information include:

• non-essential clauses

• nouns that define the same thing

• question tags.

Set off non-essential clauses

Use commas around clauses that add information but aren’t essential to the meaning of the

sentence.

Don’t use commas if the clause is essential for meaning.

If you can remove the clause and your sentence means the same thing, it’s non-essential and

should go between commas.

Non-essential clauses are also called ‘non-restrictive’ or ‘non-defining’ clauses.

Non-essential

Introduced pests, such as varroa mite, threaten Australian honey production.

[All introduced pests threaten honey production. The varroa mite is just an example.]

Essential

Introduced pests from South Asia threaten Australian honey production.

[Only pests from South Asia threaten honey production. Other introduced pests don’t affect

honey production.]

Place commas around nouns that define the same thing they follow

Use a pair of commas when you have 2 noun phrases next to each other that define the same

thing.

The strike took place in Whyalla, South Australia, in June 2014.

You should be able to take out the noun phrase between the comma pair and still have a

grammatically correct sentence.

Use commas with the phrase ‘for example’

Generally, use a comma before and after the phrase ‘for example’ in a sentence.

Some colours, for example, are difficult for people with colour blindness to distinguish.

If ‘for example’ begins a sentence, it is an introductory phrase. Follow it with a comma.

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 57

FOIREQ24/00508 0243

For example, some colours are difficult for people with colour blindness to distinguish.

If you’re introducing a bullet list after ‘for example’, use a colon.

Some colours are difficult for people with colour blindness to distinguish, for example:

• red

• green

• orange

• brown

• blue

• purple.

Place commas between

Use commas to connect 2 or more principal clauses joined by a coordinating conjunction (‘and’,

‘or’, ‘but’, ‘so’).

If they have different subjects, use a comma before the coordinating conjunction.

Do not use this rule to create a sentence of more than 25 words. Shorter sentences are easier to

read.

The Senate debated the Bill at length, but the party whips eventually called for a vote.

[‘But’ is the coordinating conjunction. ‘The Senate’ and ‘the party whips’ are each the

subjects of a principal clause.]

If 2 clauses share the same subject, you don’t need to repeat the subject or insert a comma before

the conjunction.

The company closed its Perth office and sacked the chief financial officer.

[‘The company’ closed an office and sacked an executive officer. ‘The company’ is the

subject of both clauses, joined using ‘and’.]

The exception to this rule is when you have joined more than 2 principal clauses with the same

subject.

The company closed its Perth office, sacked the chief financial officer, and opened a branch

in Singapore.

[The verbs ‘closed’, ‘sacked’ and ‘opened’ each complement the same subject: ‘the

company’. Each complement completes a principal clause.]

OAIC Style Guide 2021

Page 58

FOIREQ24/00508 0244

Punctuate sentence lists and strings of adjectives

Separate items in lists of nouns or adjectives with commas

Use commas between items in a sentence list. Avoid using a comma before the last item in the list.

This rule applies to sentence lists and sentence fragments in bullet lists. Do not punctuate the end

of a list item with a comma if it is in a bullet list.

The delegation visited Brisbane, Canberra and Adelaide.

The consultation involved businesses, sole traders and not-for-profits.

Restrict the use of the Oxford comma

If the last item combines 2 words or phrases with the word ‘and’, use a comma before that final

item. This use of the comma is known as the ‘Oxford comma’ or ‘serial comma’.

The industries most affected are retail trade, wholesale trade, and accommodation and

food services.

[‘Accommodation and food services’ is listed as a single industry category. It is set off in the

list with an Oxford comma.]