FOI 24/25-0151

FOI 24/25-0151

FOI 24/25-0151

FOI 24/25-0151

FOI 24/25-0151

FOI 24/25-0151

FOI 24/25-0151

FOI 24/25-0151

FOI 24/25-0151

Research Request – Magnetic EEG/EKG Guided-Resonance

Therapy (MeRT)

• Please provide a summary rating the quality of evidence cited and

provided by applicant

Brief

• Please provide any further research evidence of the use of MeRT as an

intervention for a child (10 years) with ASD.

• Is MeRT considered a clinical intervention and therefore not

appropriately funded through the NDIS

Date

11/11/20

Requester

s47F - personal privacy (Senior Technical Advisor TAB)

Researcher

s47F - personal privacy (Research Team Leader)

Contents

Summary ................................................................................................................................................. 2

Magnetic EEG/EKG Guided-Resonance Therapy (MeRT)........................................................................ 2

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation ......................................................................................................... 2

Is TMS a clinical intervention? ................................................................................................................ 3

Clinical settings for TMS .................................................................................................................. 3

Cost ................................................................................................................................................. 3

Scientific Evidence provided by the Brain Treatment Centre ................................................................. 3

Reference List .......................................................................................................................................... 9

Please note:

The research and literature reviews col ated by our TAB Research Team are not to be shared

external to the Branch. These are for internal TAB use only and are intended to assist our advisors

with their reasonable and necessary decision making.

Delegates have access to a wide variety of comprehensive guidance material. If Delegates require

further information on access or planning matters they are to call the TAPS line for advice.

The Research Team are unable to ensure that the information listed below provides an accurate &

up-to-date snapshot of these matters

Magnetic EEG/EKG Guided-Resonance Therapy (MeRT)

P a g e |

1

FOI 24/25-0151

Summary

• The evidence provided by the participant is generally of low quality

o Mainly consists of evidence for the use of MeRT for those with a diagnosis of PTSD

• No peer reviewed literature could be sourced on the use or efficacy of MeRT in people with

an ASD diagnosis

• There is some early evidence in favour of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) (MeRT is a

variant of TMS) for ASD, however, published literature is of low quality and must be

regarded as preliminary and insufficient to support offering TMS to treat ASD.

• MeRT/TMS are clinical interventions which must be administered by a trained and

accredited medical/health professional. It is not covered by Medicare or Private Health

Insurance

Magnetic EEG/EKG Guided-Resonance Therapy (MeRT)

Magnetic EEG guided Resonant Treatment or Magnetic e-Resonance Therapy (MeRT) is a variation of

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) where personalized treatment frequencies and output

intensities are derived from patient’s EEG data and resting heart rate.

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

Refer to NED20/281579 for an overview of repetitive TMS which is approved for use in Australia and

recommended by the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) as

treatment for treatment resistant major depressive disorders.

TMS has been around for more than two decades and has data confirming its low risk profile, and

excellent tolerability. While adult trials show promise in using TMS as a novel, non-invasive, non-

pharmacologic diagnostic and therapeutic tool in a variety of nervous system disorders, its use in

children is only just emerging.

Multiple systematic reviews investigating the use of TMS’ in children and adolescents with ASD have

been published [1-4]. All reviews concluded that:

1) Treatment led to improvements in relation to repetitive behaviours, stereotypes behaviours,

social behaviours and executive function tasks.

2) Long term gains/stability were not well reported

3) Studies are of low methodological quality (case studies, non-randomised trials), included

cohorts with significant heterogeneity and lacked any control of confounding factors

Therefore, there is urgent need for randomised controlled trials of high quality with adequate follow

up periods to test the efficacy of TMS for ASD. Currently available evidence must be regarded as

preliminary and insufficient to support offering TMS to treat ASD.

Magnetic EEG/EKG Guided-Resonance Therapy (MeRT)

P a g e |

2

FOI 24/25-0151

Is TMS a clinical intervention?

TMS is a clinical intervention and should only be administered by a professional who has undertaken

training and is credentialed in the procedure. This is commonly a psychiatrist, however, psychiatry

trainees and psychiatric nurses can perform the treatment under supervision.

In Australian clinical practice TMS should only be administered for an illness where there is adequate

evidence of clinical indication and effectiveness. This includes depression, schizophrenia and

obsessive compulsive disorder. It should be considered as a therapeutic option alongside other

treatments after detailed psychiatric assessment.

Clinical settings for TMS

• TMS treatment can be conducted safely as an outpatient procedure and is predominantly

provided in this context internationally.

• TMS treatment does not require sedation or general anaesthesia.

• All services providing TMS should have in place appropriate protocols, training and

equipment to allow for the safe and effective administration of treatment. This should

include protocols for patient assessment, monitoring during treatment, monitoring of the

quality of the provision of treatment, protocols for response to adverse events and

monitoring of outcomes

• Where TMS is conducted as an outpatient the outpatient TMS clinic should be suitably

accredited by an accepted accreditation agency such as International Standards Organisation

(ISO) or Australian Council of Healthcare Standards (ACHS)

• Devices used for TMS should be approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA)

for use in Australia or the New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority for

use in New Zealand. A service using a specific TMS device should check the intended use that

has been formal y approved by these organisations, as these can differ between devices.

Cost

In Australia, TMS is not covered by Medicare or Private Health Insurance.

Scientific Evidence provided by the Brain Treatment Centre

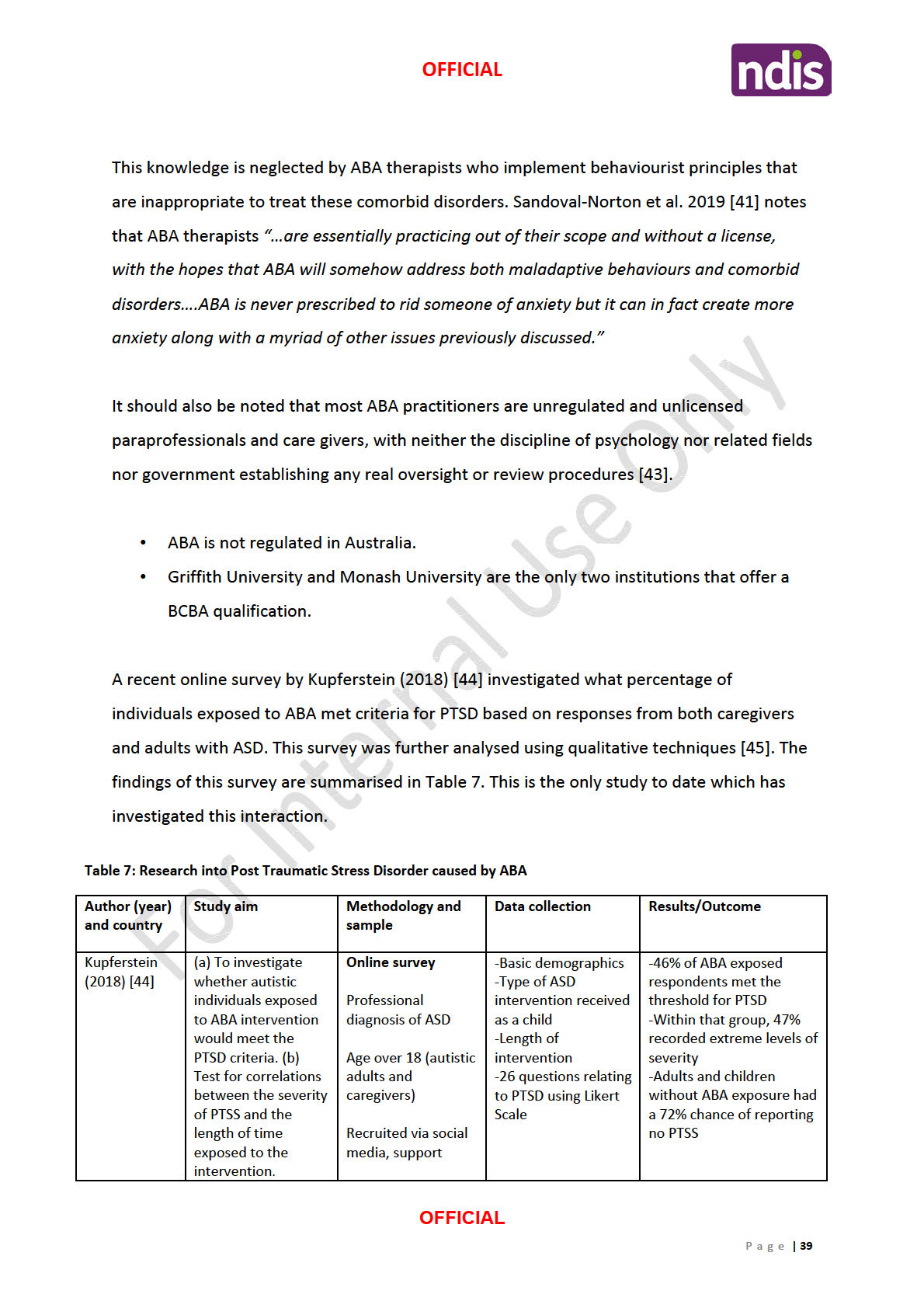

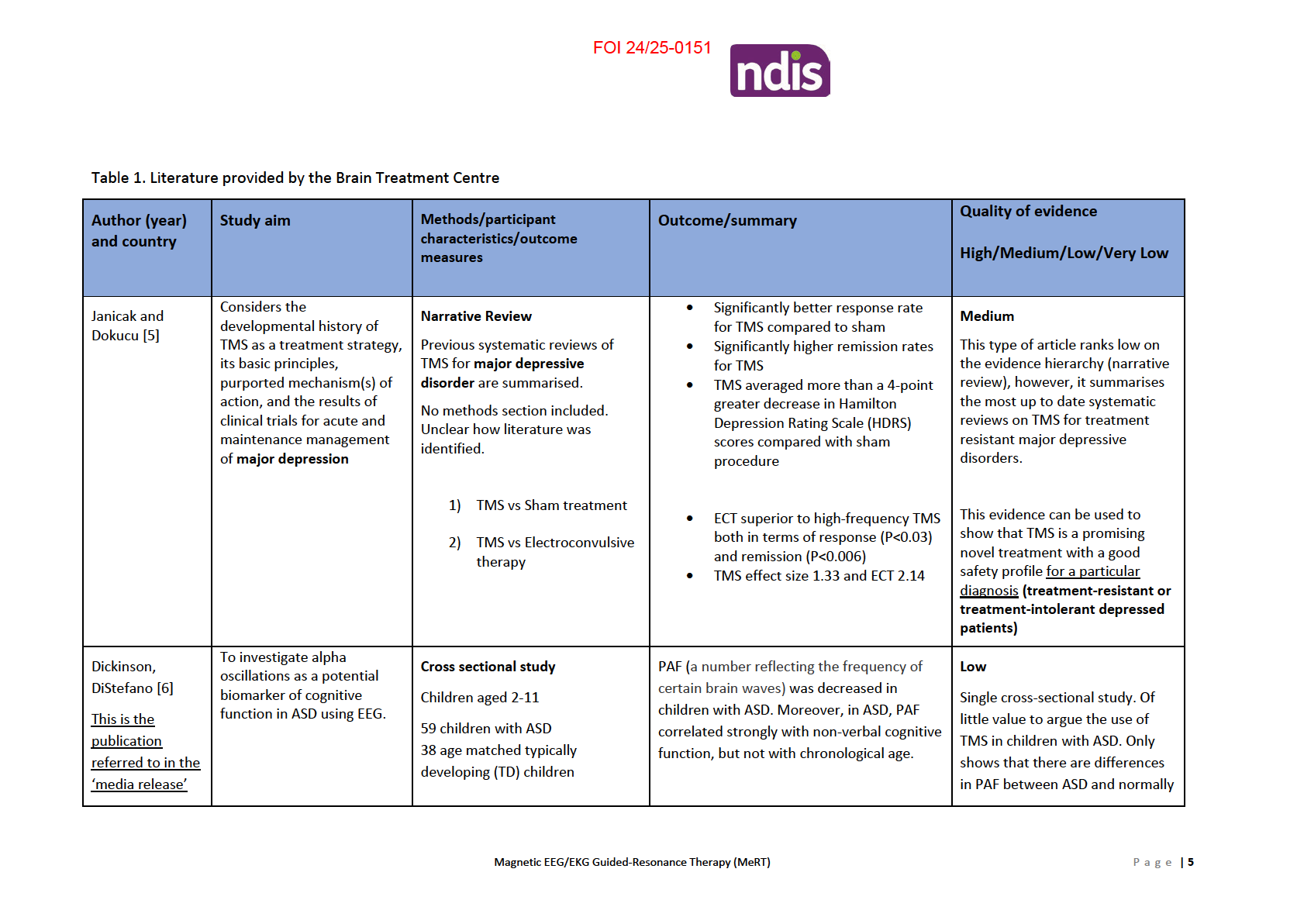

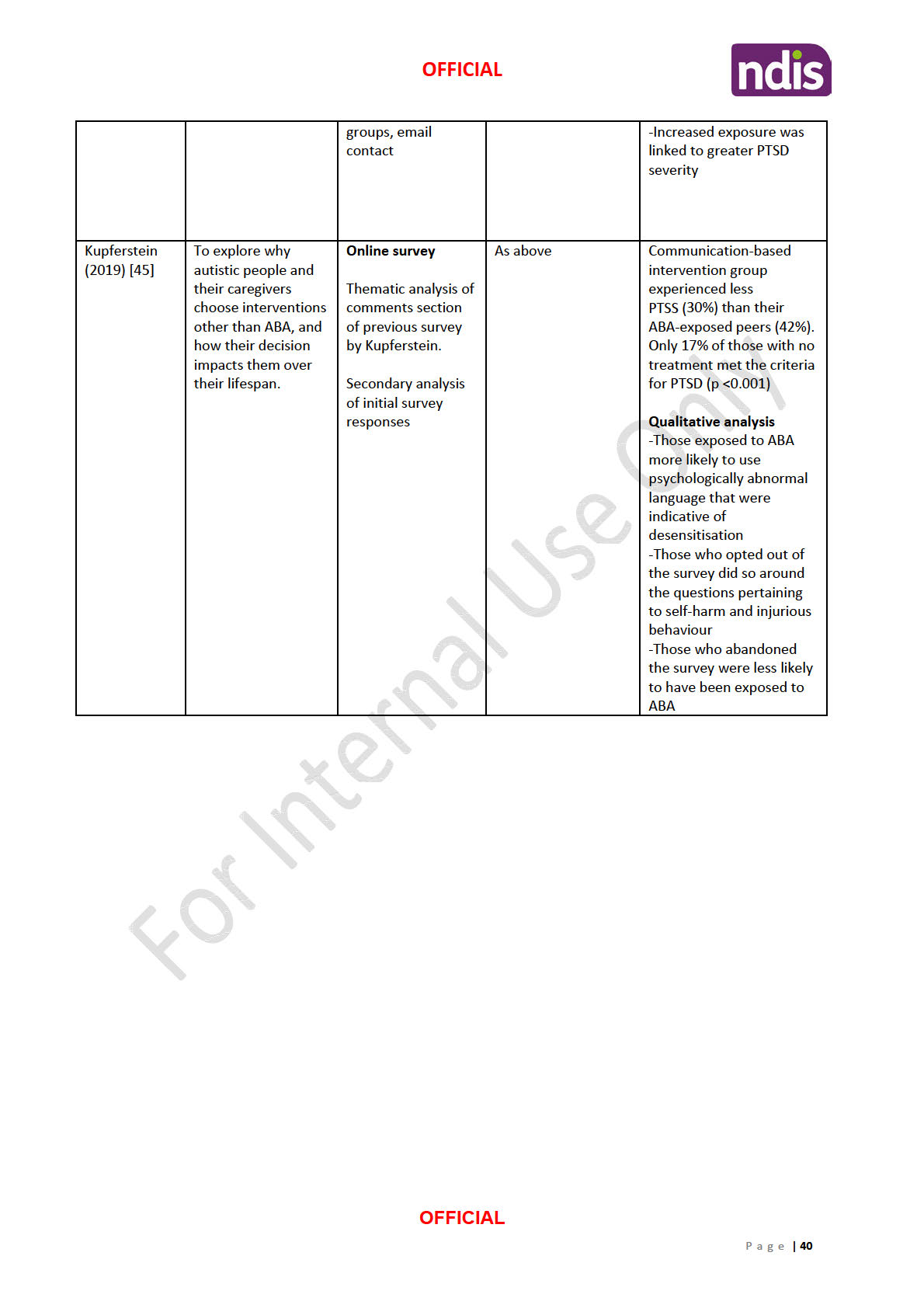

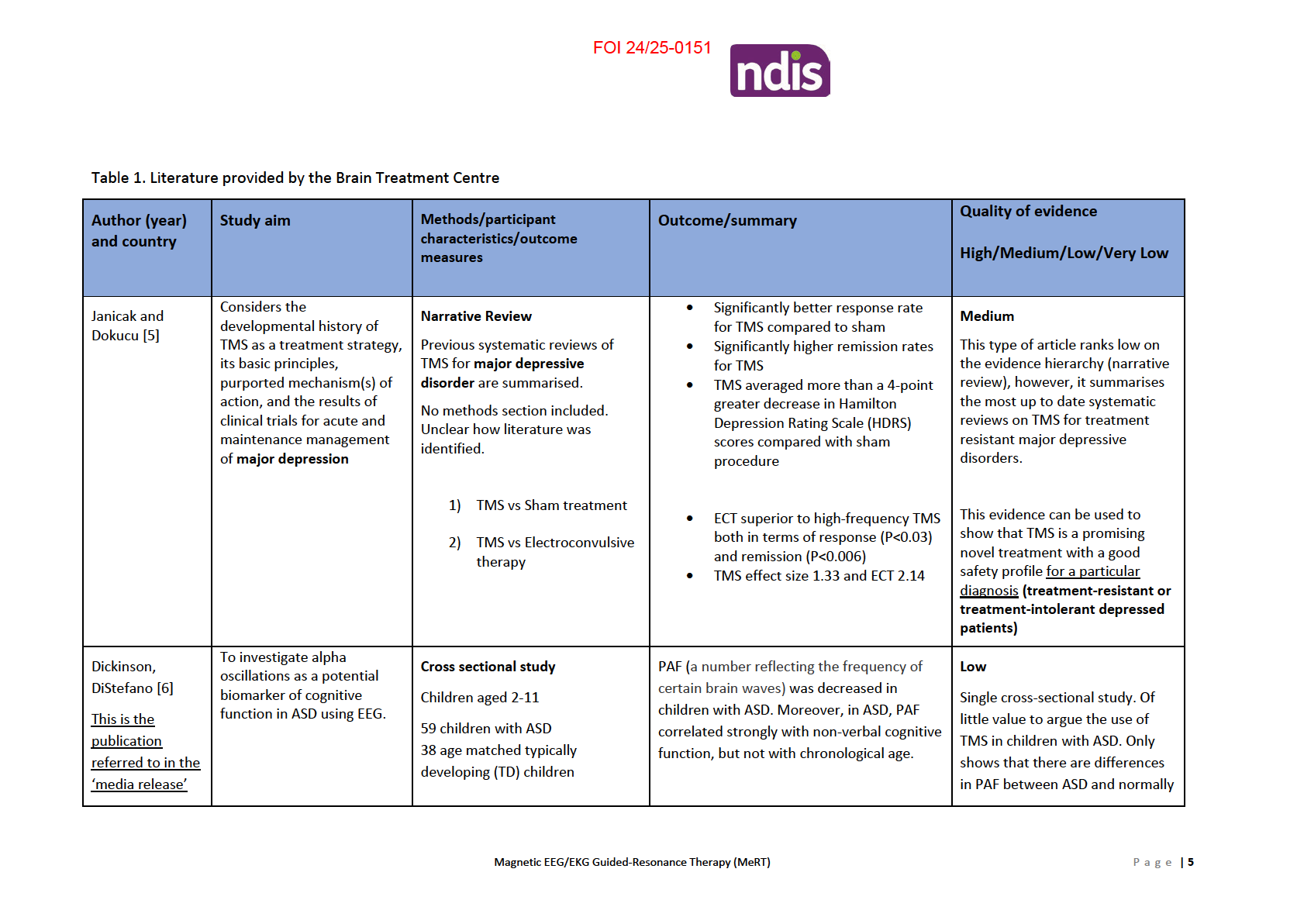

The evidence provided by the Brain Treatment Centre (Table 1) consists of:

1) Narrative review which summarises the results of systematic reviews investigating the

efficacy of TMS for major depressive disorder. This paper is of

moderate quality and shows

that TMS is a useful tool to treat

major depressive disorders but provides no scientific

information of MeRT.

2) Cross sectional study which shows that peak alpha frequency (PAF) measures from EEG

correlates with non-verbal cognitive function in children with ASD. This measure is being

claimed to have the potential to act as a biomarker in the future, to help study whether an

autism treatment is effective in restoring peak alpha frequency to normal levels. This paper

is of

medium quality, however, provides little value in the argument for MeRT. All it shows is

Magnetic EEG/EKG Guided-Resonance Therapy (MeRT)

P a g e |

3

FOI 24/25-0151

a difference in brain waves/oscillations between normally developing children and those

with ASD, not whether MeRT is appropriate or useful as a treatment for ASD.

3) A conference presentation is the only evidence provided for the use of MeRT in children

with ASD. Although results show improvements in autism behaviours the quality of the

evidence is rated as

very low as it is not peer reviewed, retrospective data col ection and

there were high dropout rates. This information should not be used as evidence for the

effectiveness of the treatment.

4) The two remaining papers include a retrospective chart review

(low quality) and an

unpublished randomised control ed trial

(very low quality). These two papers investigate

the use of MeRT in

veterans with PTSD. Both show positive results but must be assessed

with caution due to their low methodological quality, lack of peer review and potential for

bias as the studies were not performed by an independent research group (co-creators of

MeRT conducted studies).

Magnetic EEG/EKG Guided-Resonance Therapy (MeRT)

P a g e |

4

FOI 24/25-0151

provided by the

PAF may be used as a biomarker in the

developing aged matched

Brain Treatment

future, to help study whether an autism

Exclusion criteria included other

children.

Centre

treatment is effective in restoring peak alpha

neurological abnormalities

frequency to normal levels, for instance.

Furthermore, the study didn’t

(including active epilepsy), birth-

measure ASD symptoms so

related complications and

cannot infer how this may change

uncorrected vision or hearing

across severity levels.

impairment.

• Cognitive and language

assessments

• electroencephalography

(EEG) recording to

measure peak alpha

frequency (PAF)

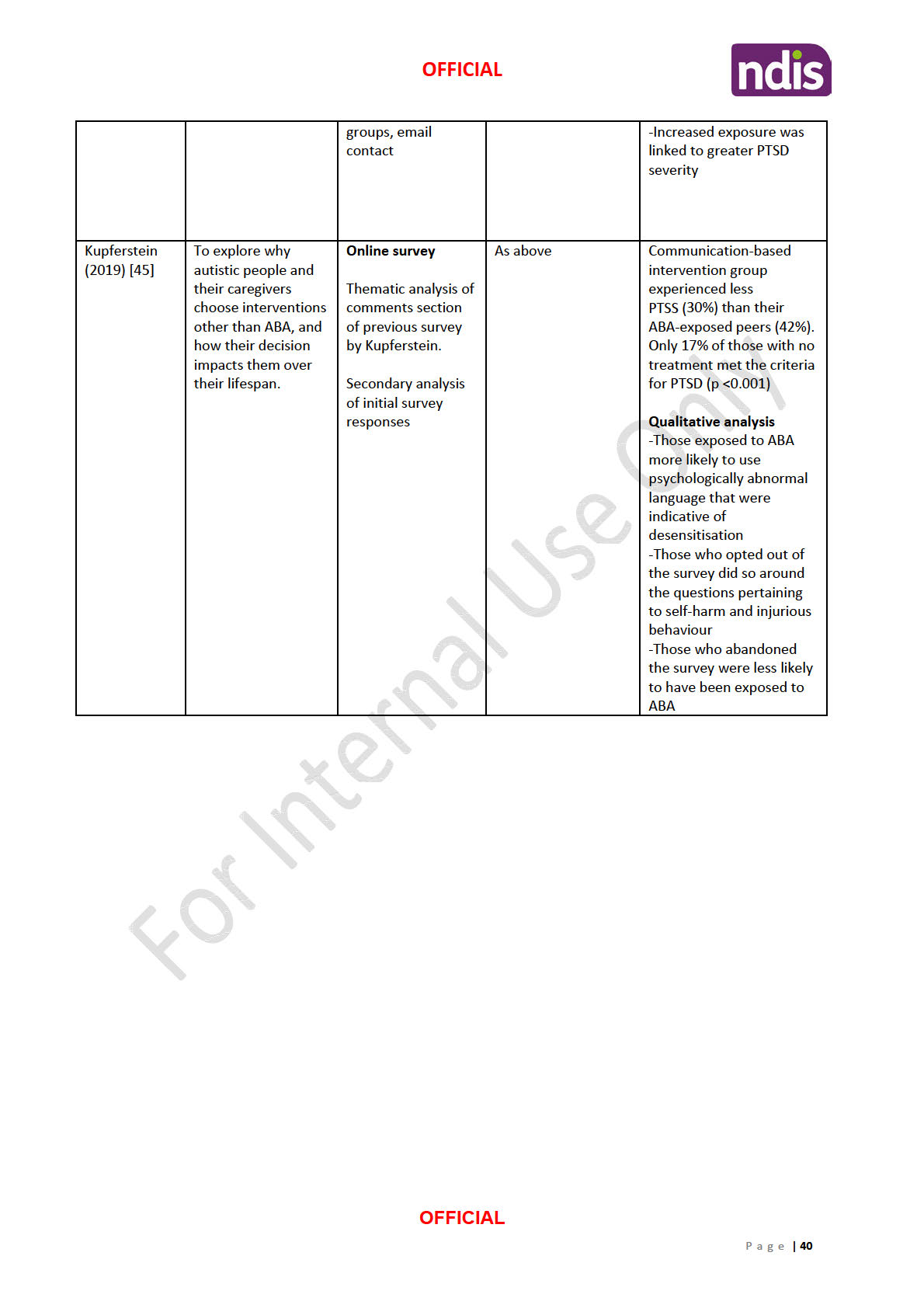

Kim and Taghva

Hypothesize behavioural

At 24 month fol ow up, 26 of 44 (59%)

improvements in autism

Conference presentation

patients showed statistical y-significant

Very Low

[7]

behaviours via TMS with

Retrospective chart review

improvements of -11.7 +/- 6.2 S.D. Ten

Non peer reviewed, retrospective,

customized frequency

patients’ CARS fel below 26 (38%) consistent high dropout rates.

modulation.

141 patients underwent TMS with with minimization of autism behaviours.

customized frequency modulation.

This literature should not be used

Serial EEGs were used to modify

Most improvements were made in Taste,

to make a clinical treatment

frequency delivered using resting

Smel , and Touch Response and Use, Fear

alpha frequency combined with

decision.

and Nervousness, and Verbal

resting heart rate.

Communication

35 patients were excluded at 1

week due to lack of improvement

on Child Autism Score (CARS).

1 patient was excluded at first

week for seizure (0.7%).

44 (41.5%) made it to the 24-

month fol ow up period.

Magnetic EEG/EKG Guided-Resonance Therapy (MeRT)

P a g e |

6

FOI 24/25-0151

Age, sex, race, other treatments,

number of treatments, CARS

scores were sub-stratified.

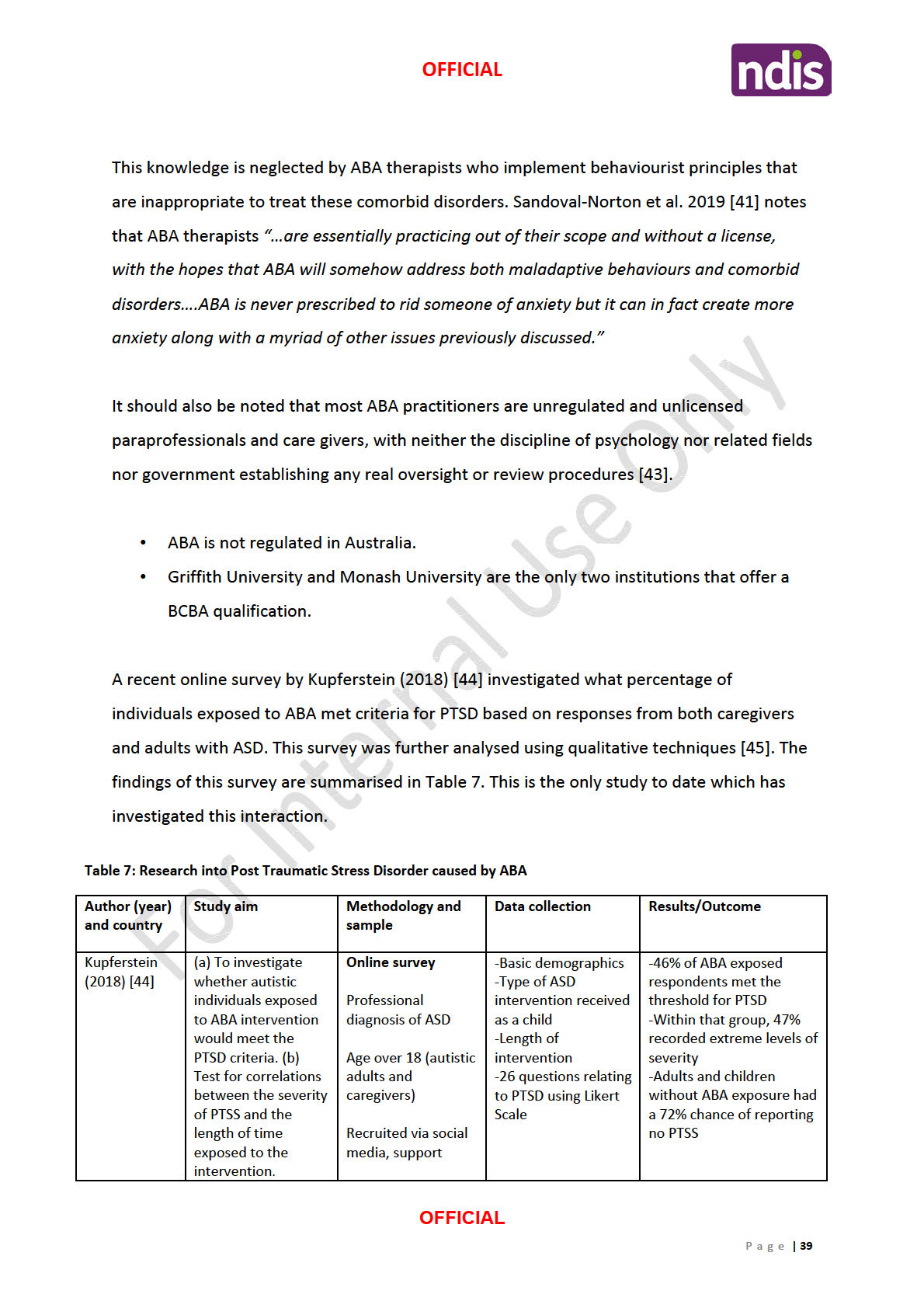

Taghva, Silvetz

To determine if magnetic

Retrospective Chart Review

Of the 21 patients who initiated therapy, 16

Low

[8]

brain stimulation can induce 21 veterans consecutively-treated (76%) completed treatment. Clinical

Smal sample, no control group,

normalization of EEG

for

PTSD.

improvements on the PCL-M were seen in

lack of long term fol ow up data.

abnormalities and improve

these 16 patients, with an average pre-

clinical symptoms in

PTSD in Magnetic resonance therapy

treatment score of 54.9 and post-treatment

The study suggests that non-

a preliminary, open-label

(MRT) was administered for two

score of 31.8 (P < 0.001). In addition, relative invasive neuro-modulation

evaluation

weeks at treatment frequencies

global EEG alpha band (8 - 13 Hz) power

magnetic resonance therapy may

based on frequency-domain

increased from 32.0 to 38.5 percent (P =

lead to clinical improvements,

analysis of each patient’s

0.013), and EEG delta-band (1 - 4 Hz) power

however, further large scale, high

dominant alpha-band EEG

decreased from 32.3 percent to 26.8 percent quality studies are required

frequencies and resting heart rate. (P = 0.028)

Patients were evaluated on the

PTSD checklist (PCL-M) and pre-

and post-treatment EEGs before

and after MRT.

Taghva, Jin [9]

To determine if MeRT can

Characteristics for the randomized groups

improve clinical symptoms in

Randomised Control ed Trial

were similar, with pre-treatment average

Very Low

PTSD in a double-blind,

86 veterans (ages 20-56, mean

PCL-M scores of 65.7 and 65.4 in the MeRT

Unpublished/non-peer reviewed,

sham control ed,

37.8; 9 female, 77 male) with prior and sham stimulation groups respectively.

no power or sample size

randomized trial.

diagnosis of

PTSD (moderate to

calculations, no information on

severe, PCL-M> 50) were

74 completed. 12 (14%) dropped out of

how participants were

randomized to receive MeRT

study

versus sham stimulation for two

recruited/selected (selection bias)

weeks, fol owed by open-label

Two-week post-treatment PCL-M in the

active treatment of both groups

control arm was

for two weeks.

51.4 (28.9% improvement), and in the

treatment arm was 42.6

MeRT was administered with pulse (47.4% improvement, F1,71 = 7.4, P < 0.01)

intensity at 80% of patient motor

Magnetic EEG/EKG Guided-Resonance Therapy (MeRT)

P a g e |

7

FOI 24/25-0151

threshold and stimulation

No adverse events (seizures, neurologic

frequency based on analysis of

deficit, worsening of pre-treatment

each patient’s EEG and resting

condition) were reported.

heart rhythm.

Patients were evaluated on the

PTSD Check List – Military (PCL-M),

at pre-treatment, weeks 2 and 4 of

treatment, and three-month

fol ow up (eight weeks post

treatment).

Exclusion criteria included history

of seizure disorder, history of

intracranial lesion, and history of

intracranial implant, prior

transcranial magnetic therapy, and

inability to adhere to the

treatment schedule.

Magnetic EEG/EKG Guided-Resonance Therapy (MeRT)

P a g e |

8

FOI 24/25-0151

Reference List

1.

Barahona-Corrêa JB, Velosa A, Chainho A, Lopes R, Oliveira-Maia AJ. Repetitive Transcranial

Magnetic Stimulation for Treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-

Analysis. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience [Internet]. 2018 2018-July-09; 12(27). Available from:

https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fnint.2018.00027.

2.

Finisguerra A, Borgatti R, Urgesi C. Non-invasive Brain Stimulation for the Rehabilitation of

Children and Adolescents With Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in

Psychology [Internet]. 2019 2019-February-06; 10(135). Available from:

https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00135.

3.

Khaleghi A, Zarafshan H, Vand SR, Mohammadi MR. Effects of Non-invasive

Neurostimulation on Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Clin Psychopharmacol

Neurosci [Internet]. 2020; 18(4):[527-52 pp.]. Available from:

http://www.cpn.or.kr/journal/view.html?doi=10.9758/cpn.2020.18.4.527.

4.

Rajapakse T, Kirton A. Non-invasive brain stimulation in children: Applications and future

directions. Translational Neuroscience [Internet]. 2013 01 Jun. 2013; 4(2):[217 p.]. Available from:

https://www.degruyter.com/view/journals/tnsci/4/2/article-p217.xml.

5.

Janicak PG, Dokucu ME. Transcranial magnetic stimulation for the treatment of major

depression. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:1549-60.

6.

Dickinson A, DiStefano C, Senturk D, Jeste SS. Peak alpha frequency is a neural marker of

cognitive function across the autism spectrum. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2018;47(6):643-

51.

7.

Kim A, Taghva A. Improved autism behaviors after noninvasive cerebral transmagnetic

stimulation using customized frequency modulation: fol ow-up mean 24 months. American

Association of Neurological Surgeons; April 5-9, 2014; San Francisco, CA2014.

8.

Taghva A, Silvetz R, Ring A, Kim K-YA, Murphy KT, Liu CY, et al. Magnetic Resonance Therapy

Improves Clinical Phenotype and EEG Alpha Power in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Trauma Mon

[Internet]. 2015; 20(4):[e27360-e pp.]. Available from:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4727473/.

9.

Taghva A, Jin T, Liu CY, Ring A, Jin Y. Biometrics-Guided Magnetic e-Resonance Therapy

(MeRT) in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Sham Controlled Trial. No

date.

Magnetic EEG/EKG Guided-Resonance Therapy (MeRT)

P a g e |

9

Document Outline