FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

DOCUMENT 1

Acquired brain injury Disability

Snapshot

SGP KP Publishing

Exported on 2024-10-18 03:09:18

Page 1 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Acquired brain injury Disability Snapshot

Table of Contents

1 Peak body consulted ........................................................................................................... 4

2 What is acquired brain injury? ........................................................................................... 5

3 Misconceptions about acquired brain injury .................................................................... 6

4 How is acquired brain injury diagnosed? .......................................................................... 7

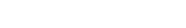

5 Language and terminology ................................................................................................. 8

6 Enabling social and economic participation ..................................................................... 9

7 How can I tailor a meeting to suit a participant with an acquired brain injury? .......... 10

8 Helpful links ........................................................................................................................ 11

Table of Contents – 2

Page 2 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Acquired brain injury Disability Snapshot

This Disability Snapshot provides general information about acquired brain injury to assist you

in communicating effectively and supporting the participant in developing their goals in a

planning meeting. Each person is an individual and wil have their own needs, preferences and

experiences that wil impact on the planning process. This information has been prepared for

NDIA staff and partners and is not intended for external distribution.

Peak body consulted – 3

Page 3 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Acquired brain injury Disability Snapshot

1 Peak body consulted

In developing this resource we consulted with Brain Injury Australia.

Peak body consulted – 4

Page 4 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Acquired brain injury Disability Snapshot

2 What is acquired brain injury?

Acquired brain injury (ABI) is a term used to describe multiple disabilities caused by damage to

the brain after birth. An ABI can result in deterioration in a person’s cognitive, physical,

emotional or independent functioning.

An ABI can occur from:

• an accident

• stroke

• brain tumour

• head trauma

• infection (such as encephalitis or meningitis)

• poisoning (alcohol or other drug abuse)

• lack of oxygen (referred to as hypoxia or anoxia) or

• degenerative neurological diseases[1].

Some ABIs result in permanent physical disability, for example - paralysis, problems with

balance and coordination, epilepsy, vision or hearing loss. Other significant impacts can be

cognitive or behavioural, for example - chal enging behaviour, poor short-term memory, reduced

attention and concentration, difficulties with learning, planning and solving problems.

Challenging behaviours may include irritability, social (sometimes sexual) disinhibition and

verbal (sometimes physical) aggression.

What is acquired brain injury? – 5

Page 5 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Acquired brain injury Disability Snapshot

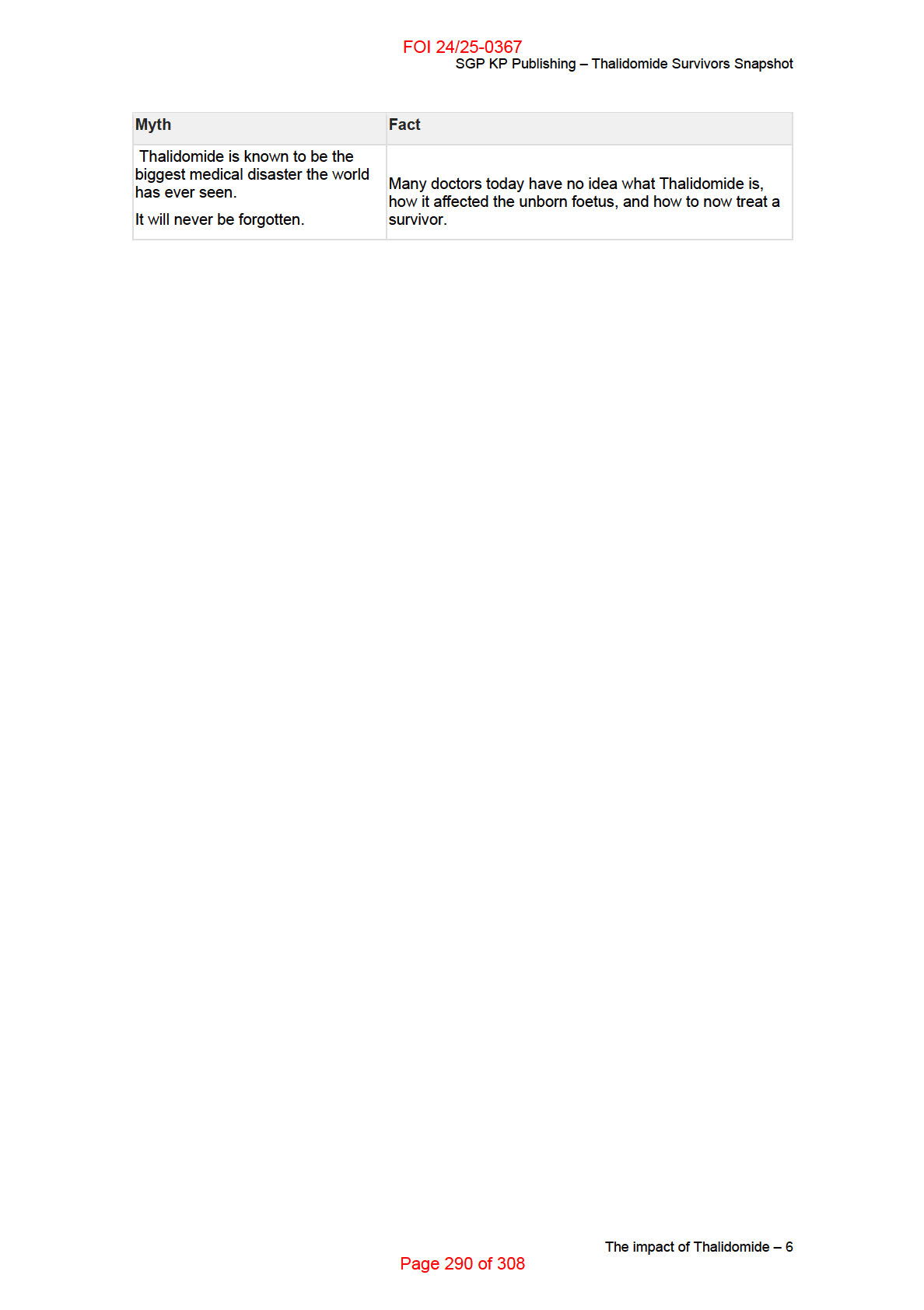

3 Misconceptions about acquired brain injury

Some misconceptions about ABI include:

• ABI is an intel ectual disability

• Recovery from an ABI doesn’t continue beyond two years.

o While the greatest improvement in function fol owing an ABI occurs in the first

two years, recovery can continue for at least five years following the injury.

• Everyone recovers from a mild traumatic brain injury.

o Approximately one in four people who have concussion/s or mild TBIs do not

make a full recovery within the expected timeframes. They can experience

ongoing physical symptoms such as headaches and dizziness, impacts on

cognition, and behaviour and/or mental il ness. For some people, the

impairment is permanent.

Misconceptions about acquired brain injury – 6

Page 6 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Acquired brain injury Disability Snapshot

4 How is acquired brain injury diagnosed?

Participants who have a severe ABI wil likely have one or more neuropsychological

assessments. Assessments include an interview and standardised tests to determine the

injury’s effects on cognition and behaviour. Recommendations are then made for therapies to

improve function.

The period of time in which the participant is unable to have continuous day-to-day memory

(duration of post-traumatic amnesia) is currently the best single predictor of severity for the

disability.

How is acquired brain injury diagnosed? – 7

Page 7 of 308

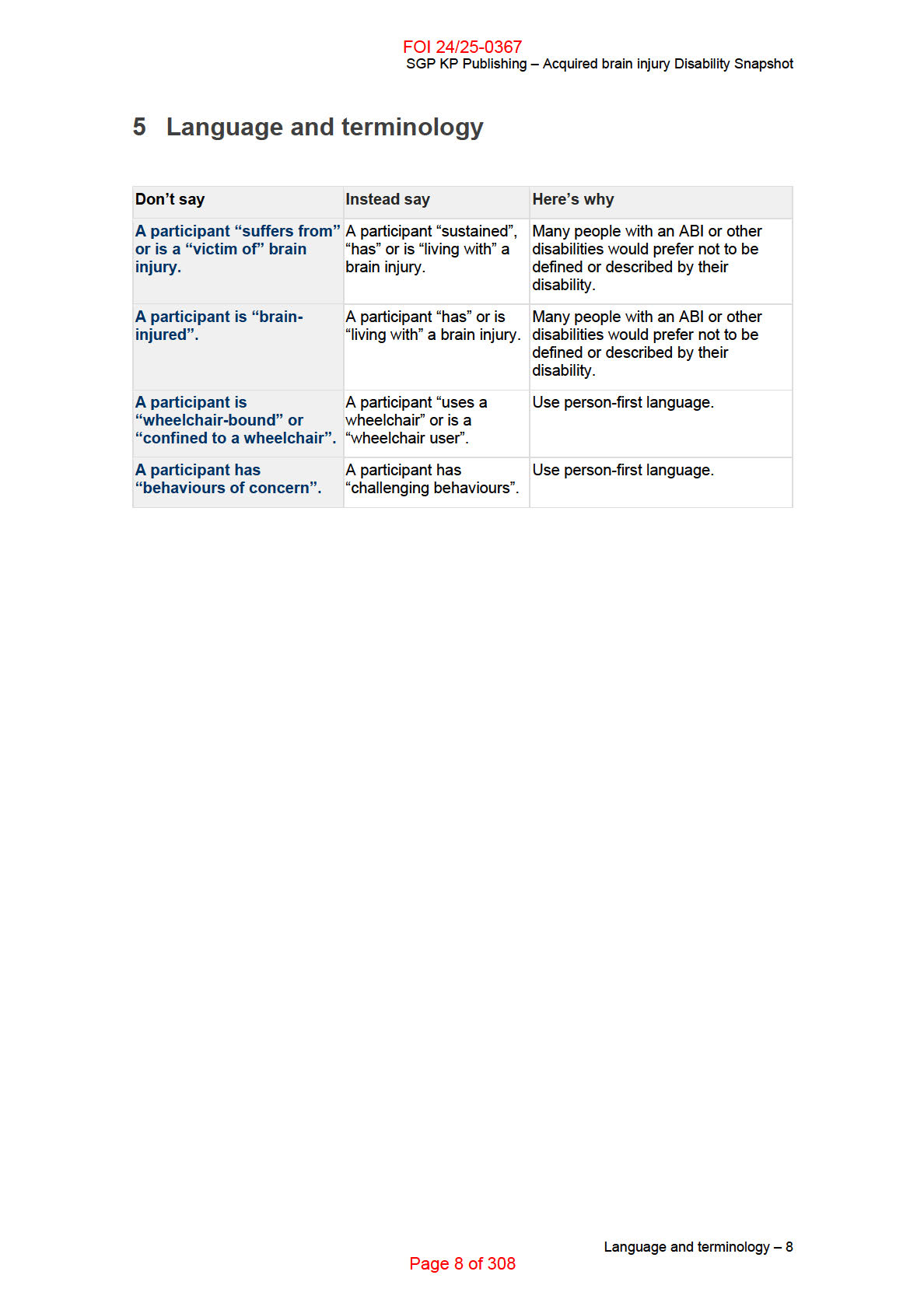

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Acquired brain injury Disability Snapshot

6 Enabling social and economic participation

The lived experience of a brain injury is usual y very different from a lifelong developmental or

intel ectual disability. People with an ABI wil likely remember what they were able to do before

their injury. Their engagement with the NDIS may be affected by grief. Some participants may

therefore have difficulty setting and achieving goals. They may also experience a breakdown in

relationships with family and friends.

The circumstances of the participant’s injury may also be associated with embarrassment or

shame, especially when the injury was, or is perceived to be, the participant’s fault. People with

an ABI have a very high lifetime risk of mental il ness, such as depression.

Help the participant adapt to their disability by reconnecting them to as much of their life before

injury as possible. For example, exploring pre-injury employment, pursuits and pastimes.

It may be appropriate to explore ways for participants to go back to their previous career or

profession with supports in place. For others, being supported through a vocational ‘discovery’

process to re-explore their strengths and interests in preparation for work could be useful.

Volunteering to build confidence and connect with the community is another way to prepare for

work.

While employers are required to make reasonable adjustments to accommodate needs in the

workplace – supports that are above and beyond this could be funded under the NDIS.

Participants may require NDIS funding for specialist disability assessment services to access

external employment retention and support initiatives, such as the Work Assist program

provided by Disability Employment Services.

Peer support from other people with ABIs can also be helpful to improve social and economic

participation.

Enabling social and economic participation – 9

Page 9 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Acquired brain injury Disability Snapshot

7 How can I tailor a meeting to suit a participant with

an acquired brain injury?

A person with ABI may recover well physically their cognitive and/or behavioural disability can

be significant. Their disability may not be obvious to someone meeting them for the first time

and that is why ABI is often referred to as an “invisible disability”.

Participants can also lack insight into their disability and be unaware of their limitations, or may

have unrealistic expectations of their recovery and/or set unrealistic goals. It is recommended,

with participant consent, to check unmet support needs with significant others, family members,

clinicians or allied health professionals.

Many people with an ABI experience tiredness and difficulties with attention and/or

concentration and reduced information-processing speed. You can tailor a meeting to suit the

participant by:

• asking their preferred meeting length and discussing any other adjustments that might

assist when scheduling a meeting

• securing a meeting location free of competing background noise or distractions

• scheduling short meetings or taking breaks during longer meetings

• checking how they are feeling during the meeting

• communicating in short, simple, sentences using plain English

• checking for understanding without questioning the participant’s intelligence, ask “did

that make sense?” rather than “do you understand what I’m saying?”.

How can I tailor a meeting to suit a participant with an acquired brain injury? – 10

Page 10 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Acquired brain injury Disability Snapshot

8 Helpful links

• Brain Injury Australia (peak body)

• Stroke Foundation (national charity)

• Synapse (service provider)

• Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation (Canadian research and prevention organisation)

[1] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

National Community Services Data Dictionary

(2014)

Helpful links – 11

Page 11 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

DOCUMENT 2

Autism spectrum disorder Disability

Snapshot

SGP KP Publishing

Exported on 2024-10-18 03:09:45

Page 12 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Autism spectrum disorder Disability Snapshot

Table of Contents

1

What is autism spectrum disorder ..................................................................................... 4

2

How is autism spectrum disorder diagnosed? ................................................................. 5

3

Language and terminology ................................................................................................. 6

4

Enabling social and economic participation ..................................................................... 7

5

Barriers to achieving economic and social participation ................................................ 8

6

How can I tailor a meeting to suit a participant with autism spectrum disorder? ...... 10

7

Peak body consulted ......................................................................................................... 12

8

Helpful links ........................................................................................................................ 13

Table of Contents – 2

Page 13 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Autism spectrum disorder Disability Snapshot

This Disability Snapshot provides general information about autism spectrum disorder to assist

you in communicating effectively and supporting the participant in developing their goals in a

planning meeting. Each person is an individual and will have their own needs, preferences and

experiences that will impact on the planning process. This information has been prepared for

NDIA staff and partners and is not intended for external distribution.

What is autism spectrum disorder – 3

Page 14 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Autism spectrum disorder Disability Snapshot

1 What is autism spectrum disorder

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD), referred to as “autism” in the remainder of this snapshot, is the

collective term for a group of neurodevelopmental conditions affecting the brain’s growth and

development. Autism can affect the way individuals interact with others and how they

experience the world around them.

Autism is a life-long condition which can impact, to varying degrees, all areas of a person’s life,

including social communication and social interaction.

The behavioural features of autism are often present before a person is three years of age but

in others they may not be recognised until their school years or later in life. The developmental

challenges, signs and/or symptoms can vary widely in nature and degree between individuals,

and in the same individual over time – that is why the term “spectrum” is used.

Autism has a strong genetic base so there may be multiple diagnoses or related conditions

within a single family and their extended family.

A person living with autism may experience:

challenges with communication and interacting with others

repetitive and different behaviours, moving their bodies in different ways

strong interest in one topic or subject

unusual reactions to what they see, hear, smell, touch or taste

preference for routines and dislike of change.

What is autism spectrum disorder – 4

Page 15 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Autism spectrum disorder Disability Snapshot

2 How is autism spectrum disorder diagnosed?

Autism is diagnosed on the basis of behavioural presentation and developmental history.

Careful developmental monitoring of social attention and communication behaviours in early life

can lead to early identification and referral for a diagnosis. A reliable diagnosis is possible from

as early as 18 to 24 months of age. Some people may be diagnosed in later childhood,

adolescence or adulthood. Diagnosis is ideally undertaken by a multidisciplinary team with allied

health and medical expertise. The DSM 5 is the most commonly used diagnostic criteria in

Australia.

How is autism spectrum disorder diagnosed? – 5

Page 16 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Autism spectrum disorder Disability Snapshot

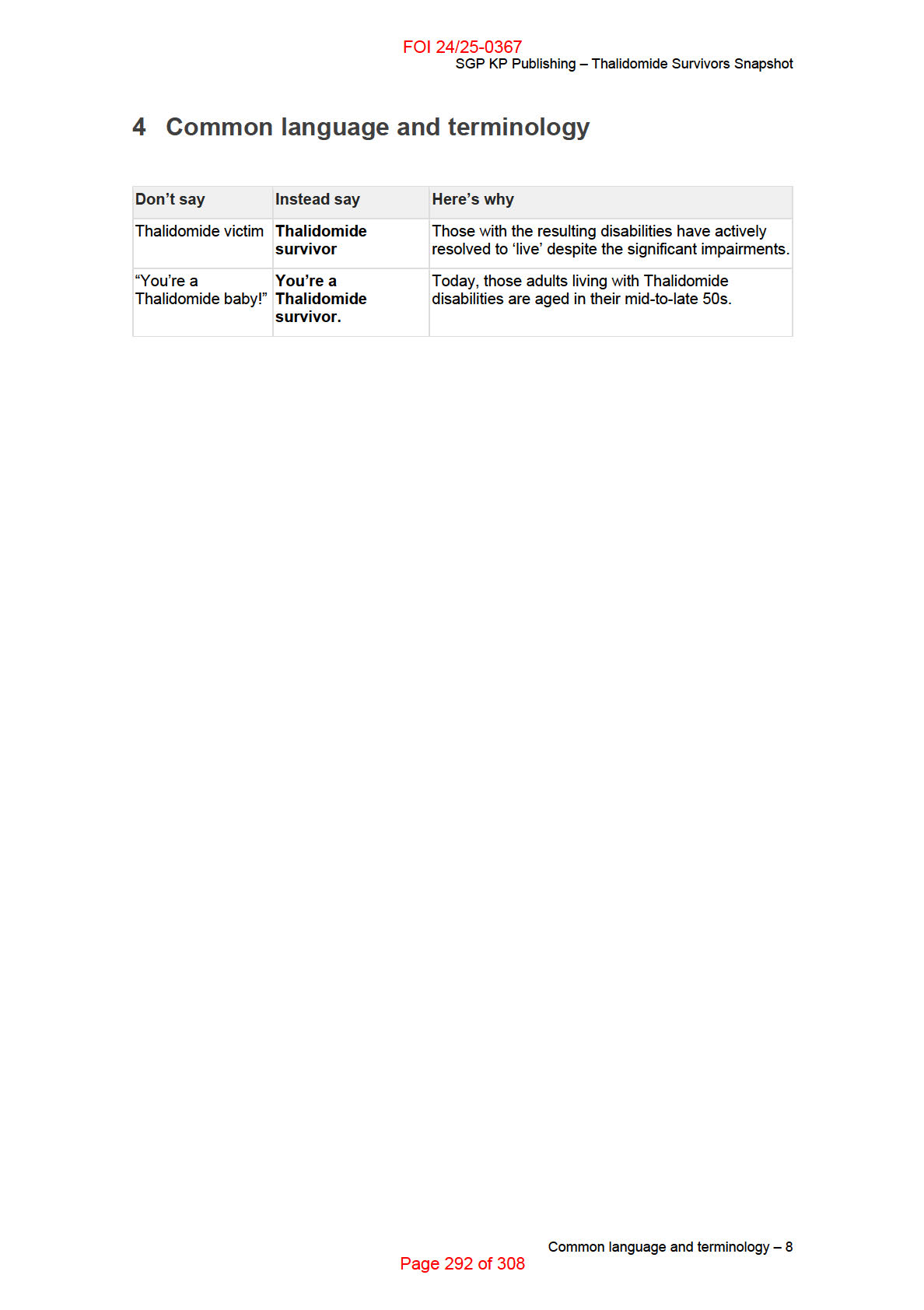

3 Language and terminology

Terminology can be a sensitive subject and reflects a range of personal perspectives.

Some families and individuals prefer “person first” language for example, “I am a person with

autism”. Others prefer “identify first” language, for example, “I am autistic”.

You should let the participant take the lead in describing themselves, their disability and their

preferred terminology. Use their preferred terminology consistently in all meetings and

correspondence.

Common terms used include:

DSM-5 - the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition. It is

published by the American Psychiatric Association and is the most commonly used tool

across the world for diagnosing psychiatric conditions and disabilities

neurodiversity - the concept that neurological differences are a natural part of human

diversity. It highlights sensitivities to words like “disorder” and “cure”

neurodivergent - is a broad term meaning atypical neurology; meaning there is a

general functional difference

neurologically typical (also referred to as NT) - a reference for people who are not on

the autism spectrum.

Language and terminology – 6

Page 17 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Autism spectrum disorder Disability Snapshot

4 Enabling social and economic participation

A person’s support needs for social and economic participation will vary depending on their

strengths and level of function.

Data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers (2015)

indicates people with autism experience poorer outcomes compared to other disability groups in

relation to education, economic participation, social participation and independent living.

Consider supports that reduce these barriers such as capacity building or support coordination.

Planning for transitions from school to higher education or work is also important.

NDIS funding can support people with autism to build life skills, capabilities and independence.

It can give them a greater understanding of what their interests are and what work might be

suitable. It can assist them build specific work related skills which could support them to engage

with other government services such as Disability Employment Services (DES).

Work adjustments or NDIS funding for specialist disability assessment services can help create

opportunities for jobs to be adapted to meet the capabilities and strengths of the individual and

to address access and lived challenge barriers as described below.

Enabling social and economic participation – 7

Page 18 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Autism spectrum disorder Disability Snapshot

5 Barriers to achieving economic and social

participation

Likely barriers to achieving similar levels of independent living, education, economic and social

participation to other disability types were identified in the ABS Survey (2015) and are listed

below.

NDIS supports can assist to address some of these barriers and improve access to social and

economic participation for people with autism. Funding for capacity building can support

participants build their planning, organisation and independent living.

Support coordination can connect participants with services and providers for assessment and

support. For example, referral to a specialist providers such as an occupational therapist can

help arrange adjustments to the physical environment for school, work or social activities.

Societal attitudes

lack of public awareness and understanding regarding autism and how it impacts on

daily living

negative media portrayal of autism

Accessibility challenges

access to timely and affordable assessments, including an understanding of the

functional impact for the individual

access to timely and appropriate supports and services following initial diagnosis and

as needs change over time

structures or physical features of the built environment, for instance lighting, noise,

smells, colours, crowding

mainstream and specialised supports and services not understanding autism or taking

individualised approaches

Lived challenges

cognitive and social differences

difficulties with planning and organisation

failure of agencies and services to work in partnership with the individual and their

friends/family to understand and address needs

experiencing bullying and harassment in schools, community settings and workplaces

failure of mainstream and disability services to provide reasonable adjustments in

education and work settings

the specific characteristics of autism (difficulties in social interactions and

communication, inflexible behaviours and routines, and executive function difficulties)

Barriers to achieving economic and social participation – 8

Page 19 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Autism spectrum disorder Disability Snapshot

may lead to increased difficulty in relationships, completing education, gaining and

maintaining employment, housing and health care

failure of services to recognise other health conditions (comorbidities) such as anxiety,

stress and depression.

Barriers to achieving economic and social participation – 9

Page 20 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Autism spectrum disorder Disability Snapshot

6 How can I tailor a meeting to suit a participant with

autism spectrum disorder?

Before a meeting

In preparation for a meeting:

provide detailed information about how and where to present for a meeting and what

the planning process will cover. Many people with autism find new events or tasks

difficult and may need

provide information at least five days before a meeting, where possible

offer a choice of meeting options such as, face to face, phone, using written and/or

verbal information

inform the individual a support person can attend

if the meeting needs to be re-scheduled or the Agency staff member attending changes,

give as much advance notice and explain the reason for the change

gather information about autism and the person you are meeting with. The participant

and their support person are best placed to inform you about their needs and

experience living with autism.

Communication during a meeting

When communicating during a meeting:

anticipate the participant may not make eye contact

consider the sensory environment, for example, sound, lights and invite the participant

to use supports to stay calm, such as, fidgets

simplify your language and use key words, natural gestures and pictures where

appropriate. Be prepared that the individual’s understanding of verbal communication

could be very literal

allow time for processing information if necessary. Pause periodically, to allow

questions and check for understanding

use positive statements as it is easier to understand positive sentences that say what to

do, rather than what not to do

sit side by side rather than face to face

acknowledge anxiety. If the individual keeps coming back to a particular issue, be

patient and allow time to answer the necessary questions to put their mind at ease

make things as predictable as possible, including running the meeting to time

allow for gender differences in the presentation of autism. Females in particular can be

adept at masking their symptoms and tend to show less severe social and

communicative symptoms. Be prepared to use gentle probing questions and draw on a

range of evidence sources to identify their support needs

How can I tailor a meeting to suit a participant with autism spectrum disorder? – 10

Page 21 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Autism spectrum disorder Disability Snapshot

consider many individuals view their autism as an important and valued part of their

personal identity. They don’t see their autism as a condition that needs to be “fixed or

cured

be aware that parents attending the meeting may also be highly stressed and anxious

or may also be a person with autism.

Planning considerations

Things to consider when developing or reviewing a participant’s plan:

focus on the functional impact of the diagnosis. Verifying the diagnosis or interpreting

reports made by health professionals can be frustrating for families and individuals who

have undergone an extensive (and costly) diagnostic process

include support coordination where there are complex needs or other health conditions

(comorbidities) that cross health, disability, community, housing and/or employment

sectors

consider and plan for life stage transitions, such as primary to high school or school to

work

remember people with autism have individual and unique needs which can change

throughout their life. It is best not to make assumptions based on your existing

knowledge and experience of autism.

How can I tailor a meeting to suit a participant with autism spectrum disorder? – 11

Page 22 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Autism spectrum disorder Disability Snapshot

7 Peak body consulted

In developing this resource we consulted with the Australian Autism Alliance, who consulted

with the following partners and supporters:

AEIOU

Foundation

Amaze

Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN AUNZ)

Australasian Society for Autism Research (ASfAR)

Autism Asperger Advocacy Australia (A4)

Autism Association of Western Australia

Autism

Co-operative

Research Centre (CRC)

Autism

Queensland

Autism

SA

Autism Spectrum Australia (Aspect)

Autism

Tasmania

I CAN; and

Autism Awareness Australia.

Peak body consulted – 12

Page 23 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Autism spectrum disorder Disability Snapshot

8 Helpful links

For further information refer to:

Australian Autism Alliance

Raising Children

Autistic Self Advocacy Network

Autism Aspergers Advocacy Australia

I Can Network

See also, service providers who are partners of the Australian Autism Alliance:

Amaze

Autism Spectrum Australia

AEIOU Foundation for Children with Autism

Autism Queensland

Autism South Australia

Autism Tasmania

Autism Association of Western Australia

Other Autism Organisations

Helpful links – 13

Page 24 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

DOCUMENT 3

Blindness and vision impairment

Disability Snapshot

SGP KP Publishing

Exported on 2024-10-18 03:09:59

Page 25 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Blindness and vision impairment Disability Snapshot

Table of Contents

1 Peak body consulted ........................................................................................................... 4

2 What is blindness and vision impairment? ....................................................................... 5

3 How is blindness and vision impairment diagnosed? ..................................................... 6

4 Language and terminology ................................................................................................. 7

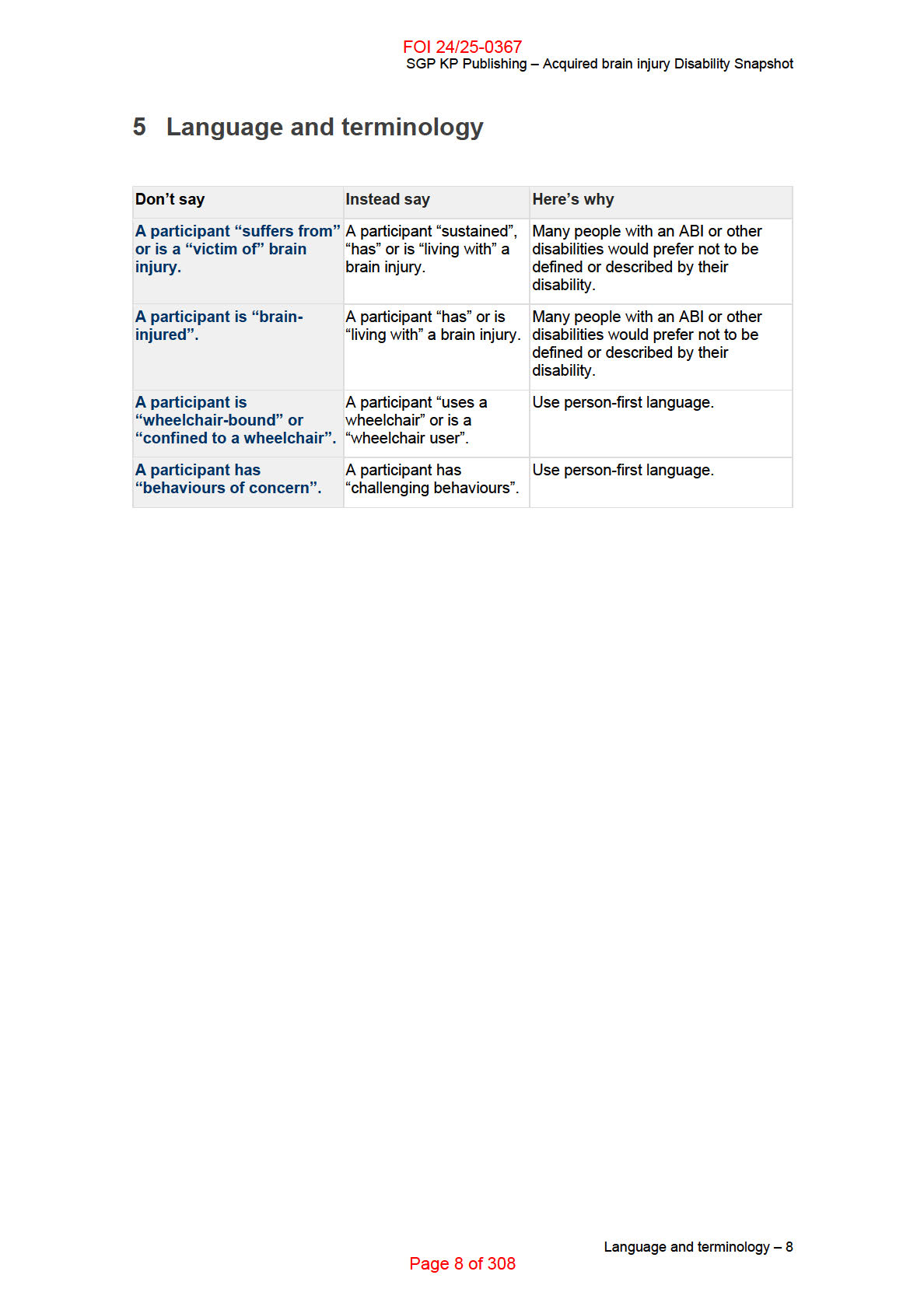

5 Communicating with people who are blind or vision impaired ....................................... 8

6 Enabling social and economic participation ..................................................................... 9

7 How can I tailor a meeting to suit a participant with blindness and vision

impairment? ............................................................................................................................... 10

8 Helpful links ........................................................................................................................ 12

Table of Contents – 2

Page 26 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Blindness and vision impairment Disability Snapshot

This Disability Snapshot provides general information about blindness and vision impairment. It

wil assist you in communicating effectively and supporting the participant in developing their

goals in a planning meeting. Each person is an individual and wil have their own needs,

preferences and experiences that wil impact on the planning process. This information has

been prepared for NDIA staff and partners and is not intended for external distribution.

Peak body consulted – 3

Page 27 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Blindness and vision impairment Disability Snapshot

1 Peak body consulted

In developing this resource we consulted with Blind Citizens Australia.

Peak body consulted – 4

Page 28 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Blindness and vision impairment Disability Snapshot

2 What is blindness and vision impairment?

Blindness and vision impairment is a sensory disability that affects a person’s access to social,

economic and physical participation. It reduces access to information, in particular written

information. This affects the person’s ability to independently work, socialise and safely go

about their lives in the community.

While more than 453,000 Australians are blind or vision impaired, the number of people eligible

for the NDIS based on the primary disability of blindness or vision impairment is much smal er.

This is because blindness and vision impairment is primarily associated with the ageing

process.

What is blindness and vision impairment? – 5

Page 29 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Blindness and vision impairment Disability Snapshot

3 How is blindness and vision impairment diagnosed?

Some people are born blind or with a vision impairment. Others may acquire it later in life,

through a genetic eye condition or accident. Some conditions are degenerative and get worse

over time.

Eye specialists such as optometrists and ophthalmologists diagnose vision impairments.

Orientation and mobility specialists train people who are blind or vision impaired to use mobility

aids and assistive technologies. Occupational therapists provide training and advice with

independent living skil s.

How is blindness and vision impairment diagnosed? – 6

Page 30 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Blindness and vision impairment Disability Snapshot

4 Language and terminology

Language shapes the way we view the world. The words we use can have a powerful effect.

How we write and refer to people with disability can affect the way they are viewed by the

community. Some words can degrade and diminish people with a disability.

Person-first language places the person first and the impairment second. Person-first language

is used to acknowledge that a disability is not as important as the person’s individuality or

humanity.

Persons with disability or people with disability are the most commonly used terms in Australia.

If you are not sure of the correct words to use, don’t be afraid to ask. Focus on the person,

rather than their disability. Offer an apology if you feel you’ve said the wrong thing and always

be wil ing to communicate.

Language and terminology – 7

Page 31 of 308

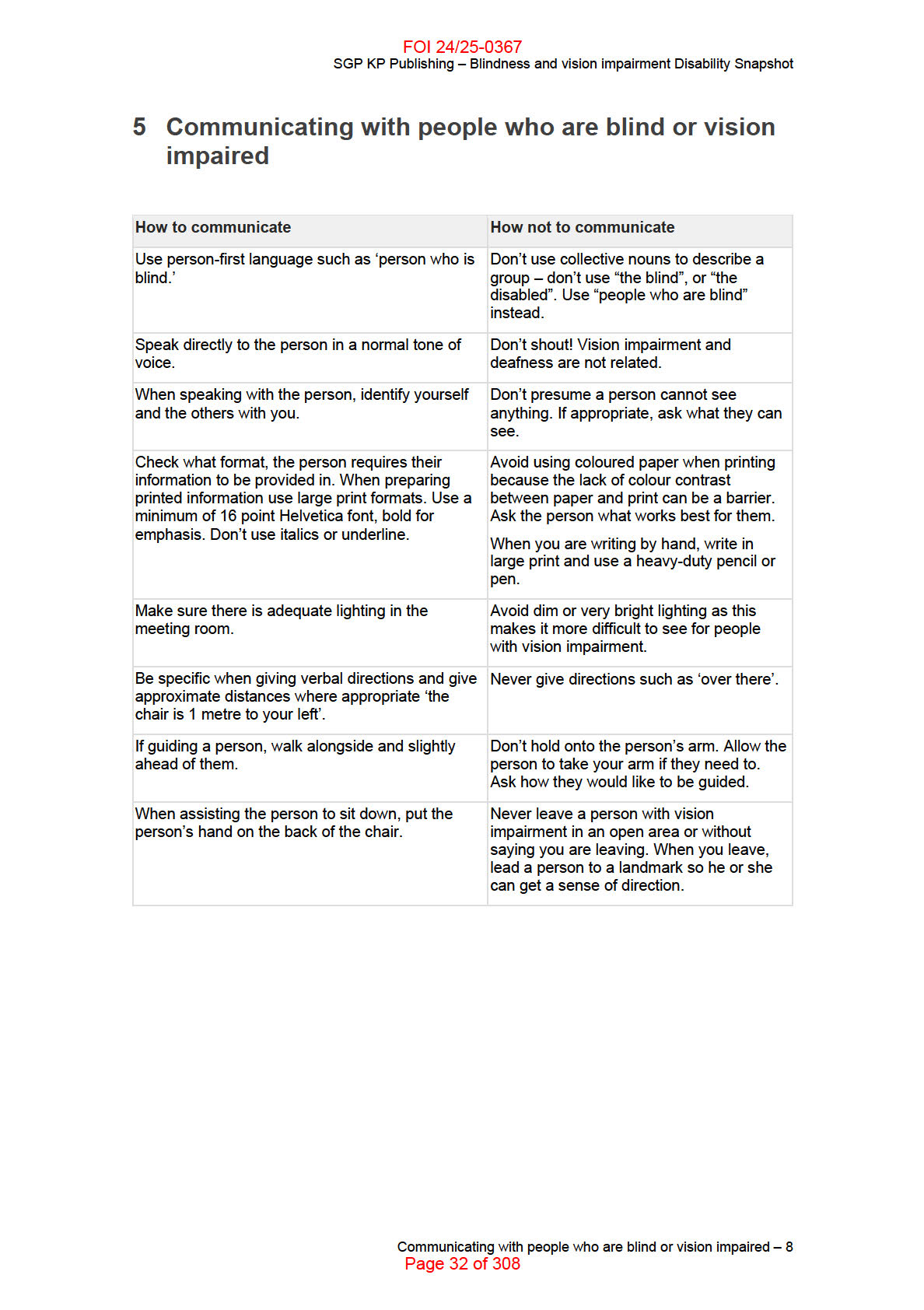

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Blindness and vision impairment Disability Snapshot

6 Enabling social and economic participation

Busy, cluttered and visual y oriented environments can be a major barrier to participation in

normal life, like; going to the shops, going for a walk in the park, going to work, looking for work

or simply socialising.

Work enables an individual to establish greater financial security, develop a sense of

productivity, purpose and make new connections with people in their community.

People who are blind or vision impaired can come up against attitudinal barriers which

compromise their dignity and independence. For example, some employers’ negative attitudes

or lack of knowledge contribute to the high rate of unemployment amongst people who are blind

or vision impaired–a rate which is four times the national average. This has a dramatic impact

on the inclusion and participation of people who are blind or vision impaired.

Assistive technology may also be required to support participation in work. To enable and

maintain work, ongoing supports or adjustments at work may be needed. This might require

NDIS funding for specialist disability or employment related assessment services. Alternatively

the person can access external employment retention and support initiatives such as Work

Assist provided by the Disability Employment Services (DES) program.

Enabling social and economic participation – 9

Page 33 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Blindness and vision impairment Disability Snapshot

7 How can I tailor a meeting to suit a participant with

blindness and vision impairment?

When meeting someone who is blind or vision impaired for the first time, they may not see your

extended hand to shake hands in greeting. Tel ing someone that you would like to shake their

hand is appropriate. Otherwise a friendly verbal greeting is okay.

Glossy brochures wil not attract or be useful to people who are blind or have minimal usable

vision. Think about other ways to share information such as information on a website (which

meets web accessibility standards, W3C), large print information with good contrast, audio

format, brail e or information over the phone.

Prior to a meeting, it is important to ask the person their preferred format for accessing

information. That way the planner can organise material in their preferred format.

During telephone conversations, especial y when organising planning meetings or other

information, encourage the person who is blind or vision impaired to make note of any times,

dates and contact information. Ask if they would like the details for the meeting and contact

information sent to them or a reminder call the day before. It is important this information is

provided in the person’s preferred communication format.

When you are planning the meeting, discuss if it wil be held at their home or another location. If

another location, ask if they wil be bringing a support person along with them. Ask what they

need from you to create an accessible environment, for example, meeting them at the entrance.

Keep in mind each person’s requirements may differ.

Verbal communication

• No matter how well you know a person who is blind or vision impaired, it is good

practice to introduce yourself when you approach the person, particularly if you are both

away from your usual environment. A simple ‘Hi Sarah, it’s John’ can help a person who

is blind or vision impaired know who has approached.

• It’s okay to use the word ‘see’ ‘see you later’ and ‘look’ ‘do you mind taking a look at

this?’ People who are blind or vision impaired use these words too.

• Talk to the person, not their guide dog.

Written communication

• Not al people who are blind read brail e. Some use brail e for reading, labelling,

identifying items or to read signs. Some don’t use brail e at all.

• How people read information can come down to personal choice, convenience and

ease. Some people with usable functional vision might use standard print or large print

(san serif font like ‘Arial’ in size 16 or greater), audio format, electronic formats (such as

word documents, html, or rtf), brail e or a number of these formats depending on the

task they are working on.

How can I tailor a meeting to suit a participant with blindness and vision impairment? – 10

Page 34 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Blindness and vision impairment Disability Snapshot

• Pictures, symbols, tables and a host of other marketing tools can be inaccessible,

depending on the technology the person is using. Therefore it’s important to check with

the person what works best.

• Word documents, html and rtf formats are a lot easier to read for people who use

screen-reading software.

• When offering information in accessible formats, offer large print, brail e, audio, or

electronic versions. Refer to Round Table Guidelines for producing information in

accessible formats.

How can I tailor a meeting to suit a participant with blindness and vision impairment? – 11

Page 35 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Blindness and vision impairment Disability Snapshot

8 Helpful links

• Blind Citizens Australia (BCA)

• Video featuring Graeme Innes AM from the NSW Government’s 2015 Don’t Dis my

Ability campaign.

• Blog post: A day in the life with Stargardts disease, Matt De Gruchy.

• Blog site, Where’s Your Dog? Article: My Roommate is Blind – Help!

• Dialogue in the Dark – an experiential awareness raising tour, led by people who are

blind or vision impaired.

Helpful links – 12

Page 36 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

DOCUMENT 4

Carers Disability Snapshot

SGP KP Publishing

Exported on 2024-10-18 03:10:11

Page 37 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Carers Disability Snapshot

Table of Contents

1 Peak body consulted . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

2 About carers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

3 Carers and the NDIS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

4 Why respite is important . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

5 Can a plan include NDIS funding for respite? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

6 How can I help carers to sustain their capacity to provide informal supports? . . . . . . 9

7 Case study examples of respite supports . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

7.1 Short-term accommodation for Peter ............................................................................... 10

7.2 Short-term accommodation for Henry .............................................................................. 10

7.3 Access to the community for Jordan ................................................................................ 11

7.4 In home supports and personal care for Sami ................................................................. 11

7.5 In home supports and personal care for Eleesha ............................................................ 11

8 Helpful links . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Table of Contents – 2

Page 38 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Carers Disability Snapshot

This Disability Snapshot provides general information about carers to assist you in

communicating effectively and supporting the participant in developing their goals in a planning

meeting. Each person is an individual and wil have their own needs, preferences and

experiences that wil impact on the planning process. This information has been prepared for

NDIA staff and partners and is not intended for external distribution.

Peak body consulted – 3

Page 39 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Carers Disability Snapshot

1 Peak body consulted

In developing this resource we consulted with Carers Australia, the national peak body

representing Australia’s unpaid carers.

Peak body consulted – 4

Page 40 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Carers Disability Snapshot

2 About carers

The sustainability of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) depends on the capacity

and wil ingness of family and friend carers to provide informal supports and unpaid care.

Australian Bureau of Statistics’ data from 2015 revealed that:

• 26% of primary carers (who provide the most substantial care for someone with

disability, chronic il ness, mental health condition or is frail or aged) had been caring for

between 5 and 9 years and 28% had been caring for between 10 and 24 years

• 33% of carers were providing care for 40 hours or more per week and in many cases,

substantially more

• 50% of primary carers identified that caring had one or more negative impacts on their

physical or emotional wellbeing

• 36% indicated they were weary and lacked energy

• 12% said they frequently felt angry and resentful

• 48% reported interrupted sleep

• 12% had been diagnosed with a stress related il ness.

About carers – 5

Page 41 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Carers Disability Snapshot

3 Carers and the NDIS

Families and carers make a valuable contribution to supporting participants. It is important to

take the time to listen to carers and support them in their role. They are often the greatest

advocates for participants.

The participant statement in a participant’s plan contains important information about the

participant’s life, their living arrangements, relationships and plan goals. As part of the

discussion to complete the participant statement, consider what may be required to strengthen

and build the capacity of those providing informal support.

The family questionnaire,

usually completed during a planning meeting

is an opportunity to

capture the experience of the family or care giver and discuss whether they have sufficient

support to provide care. A number of organisations have developed pre-planning guidance for

families and carers to assist them identify their own caring role. If they choose to, a carer can

also provide a carer statement. To access the Carers Australia Carers Checklist refer to the

Helpful links section below.

Carers and the NDIS – 6

Page 42 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Carers Disability Snapshot

4 Why respite is important

While families and carers take pleasure and satisfaction in supporting their loved ones, they

may experience stress from caring. Carers often need support and relief. They may need to

take a break from time-to-time to sustain their own wellbeing, their relationships with others and

their capacity to continue caring.

Respite can reduce carers’ stress and give them an opportunity to recharge their batteries. It

can also assist them in continuing to provide quality care.

Respite can also assist participants. A period in short-term accommodation or participation in

community activities can provide opportunities to experience new environments, make new

social connections and in some cases, develop new skil s.

Why respite is important – 7

Page 43 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Carers Disability Snapshot

5 Can a plan include NDIS funding for respite?

Funding for respite is available under the NDIS. Respite aims to support ongoing caring

arrangements between participants and their carers by providing carers with short term breaks

from their caring responsibilities.

Participants can purchase a number of supports through their NDIS plan for respite

arrangements including:

• short-term accommodation

• temporary periods of extra personal supports so that the participant can remain at home

when families and/or carers are not available

• support to participate in community activities, resulting in a break for carers.

The NDIS funds reasonable and necessary supports that facilitate respite and build

independence, offer time away from the home or provide supports in the home. Examples are

provided in the case studies below. These supports can reduce the demand on carers and give

them a break from caring responsibilities.

Can a plan include NDIS funding for respite? – 8

Page 44 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Carers Disability Snapshot

6 How can I help carers to sustain their capacity to

provide informal supports?

Let carers know that, while the NDIS supports the goals and aspirations of the participant(s)

they are caring for, it recognises that supporting family and friend carers in their caring role is

also important.

Al ow carers to explain to you the type of care and amount of care they provide. Carers should

feel comfortable to be able share any concerns they have about their capacity to continue

providing their current level of care. If they are unwil ing to raise these issues in the presence of

the person they care for, a written carer statement can be provided. Refer to the Helpful links

section below for examples.

Explain to carers how the participant’s plan can be used to purchase supports like short term

accommodation which offers value for the participant and a break for carers.

How can I help carers to sustain their capacity to provide informal supports? – 9

Page 45 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Carers Disability Snapshot

7 Case study examples of respite supports

Taking the time to listen to families and carers may identify innovative supports that facilitate

respite. Several examples are included in the case studies below to demonstrate different

arrangements.

7.1 Short-term accommodation for Peter

Carl, aged 64, and Sophie, aged 59, care for their adult son, Peter, who has cerebral palsy,

poorly controlled epilepsy, an intellectual impairment and respiratory problems. Carl and Sophie

immigrated to Australia in 1990 and would like to travel to their home country to visit their elderly

parents and catch up with other family and friends. They plan to spend three weeks overseas.

They don’t believe they can manage taking Peter with them. Carl and Sophie have no friends or

family members able to provide care in their absence so they wil need to explore alternative

accommodation options for Peter while they are overseas.

In this situation funding for short-term accommodation in Peter’s plan wil allow his parents to

take a break from their caring role. It wil also benefit Peter by having some experience with

other carers and environments. This is important preparation for when Carl and Sophie won’t be

able to care for Peter at home because his parents are getting older. Peter supports his parents’

request.

7.2 Short-term accommodation for Henry

Henry, aged 9, has severe autism and regularly has difficulty controlling his behaviour which

includes physical and emotional aggression. This behaviour often occurs for several hours at a

time and typically at night. Despite therapeutic interventions these behaviours are stil occurring

and employment of an in-home support worker is not suitable.

Henry’s parents are constantly hyper-vigilant and preoccupied with attempts to reduce

behavioural outbursts. They find it difficult to find the time and energy to give enough attention

to their other two children or to each other. The situation is taking a significant toll on Henry’s

family members and their relationships.

The family would like to include funding in Henry’s plan for regular short-term accommodation.

This wil allow his parents and siblings to strengthen their resilience and bond as a family by

spending time together. It is also intended to give Henry the opportunity to undertake new

activities and interact with other children guided by specialised professional carers.

Case study examples of respite supports – 10

Page 46 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Carers Disability Snapshot

7.3 Access to the community for Jordan

Jordan, aged 13, lives with his parents and sister in a regional area. He has severe intellectual

and language delays and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. He is unable to talk, has

behavioural concerns and needs constant supervision and help with daily living activities. Each

Saturday Jordan participates in a three-hour group activity that allows him to access the

community with his friends, develop social skil s and independence. The group meets in a town

that is one and a half hours’ drive from home.

Jordan’s parents have asked that the transport costs and a support worker to accompany him to

each group session be included in his plan. This wil enable them to have respite and to spend

time together and with their other child.

Without this support, one parent would need to drive Jordan to the activity and stay in the town

while he is participating. The NDIS planner could consider that the transport of this distance to a

community activity exceeds ordinary parental responsibilities, provides Jordan with an

opportunity to meet his goals and objectives while providing a break for his parents.

7.4 In home supports and personal care for Sami

Sami, aged 18, is the sole family carer for her mother, Sara, who has advanced multiple

sclerosis and suffers from severe depression. Sami manages the household duties, including

looking after her 10 year old brother, as her mother cannot. While Sara receives paid personal

care and some household assistance during the day until Sami comes home from school, she is

very often in pain and in need of assistance throughout the night. This seriously interferes with

Sami’s sleep. Sara feels very guilty about the situation and the negative affect it is having on

Sami. This compounds her depression.

As well as paid carer support between the hours of 8.30am and 3.30pm on school days, Sara

would like funding in her NDIS plan for some over-night support during the week. This wil

relieve Sami from providing overnight care, improve her general wellbeing, and her capacity to

engage in education. This would also have a positive effect for Sara and her ongoing well-

being.

7.5 In home supports and personal care for Eleesha

Katerina is the primary carer of her three year old daughter Eleesha, who has a congenital heart

disease, stroke and developmental delay. Complications from her medical conditions have

resulted in the loss of a kidney, damage to her spleen and a reduced ability to fight infections.

Because of Eleesha’s susceptibility to infections she is becoming increasingly isolated with little

interaction with anyone other than her parents. Katerina is also feeling isolated. However, while

Case study examples of respite supports – 11

Page 47 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Carers Disability Snapshot

Eleesha would benefit from the opportunity to develop independence and social skil s ordinarily

provided by attending child care, she is unable to attend a child care centre because contact

with other children increases her risk of infection.

Katerina would like Eleesha’s NDIS plan to include funding for regular in-home support. This

would have the benefit of providing Eleesha with the opportunity to interact with people other

than her parents and develop social skil s, as well as enabling Katerina to have some time for

herself. Katerina is also considering returning to part time employment.

Case study examples of respite supports – 12

Page 48 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Carers Disability Snapshot

8 Helpful links

• While the section on the NDIS and carers on the Carers Australia website is primarily

designed to help carers understand the NDIS, it is also a useful resource for NDIA staff

and partners to understand the carer’s perspective.

• Carers Australia Carer Checklist. Carers are encouraged to fil out this checklist prior to

engaging with the planning process. It also provides planners with some useful insights

into the range and diversity of supports which carers provide and the ways in which

caring can impact on their own lives and wellbeing. It may be useful to provide the

checklist to carers and family members to help them prepare for a planning meeting.

• Carer Statement examples. These may help planners understand why in some cases it

may be important for both the participant and the NDIA for carers to have an

opportunity to tell their own story without having to do so in front of the participant.

o Carer statement

o Primary carer’s statement

• How to speak NDIA guide on the Endeavour Foundation website. This can assist in

understanding some of the communication problems which arise between NDIA

professionals, participants and their carers.

Helpful links – 13

Page 49 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

DOCUMENT 5

Cerebral palsy Disability Snapshot

SGP KP Publishing

Exported on 2024-10-18 03:10:27

Page 50 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Cerebral palsy Disability Snapshot

Table of Contents

1 What is cerebral palsy? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

2 Different types and measures for describing cerebral palsy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

3 Common characteristics and impacts of cerebral palsy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

4 Common misconceptions about cerebral palsy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

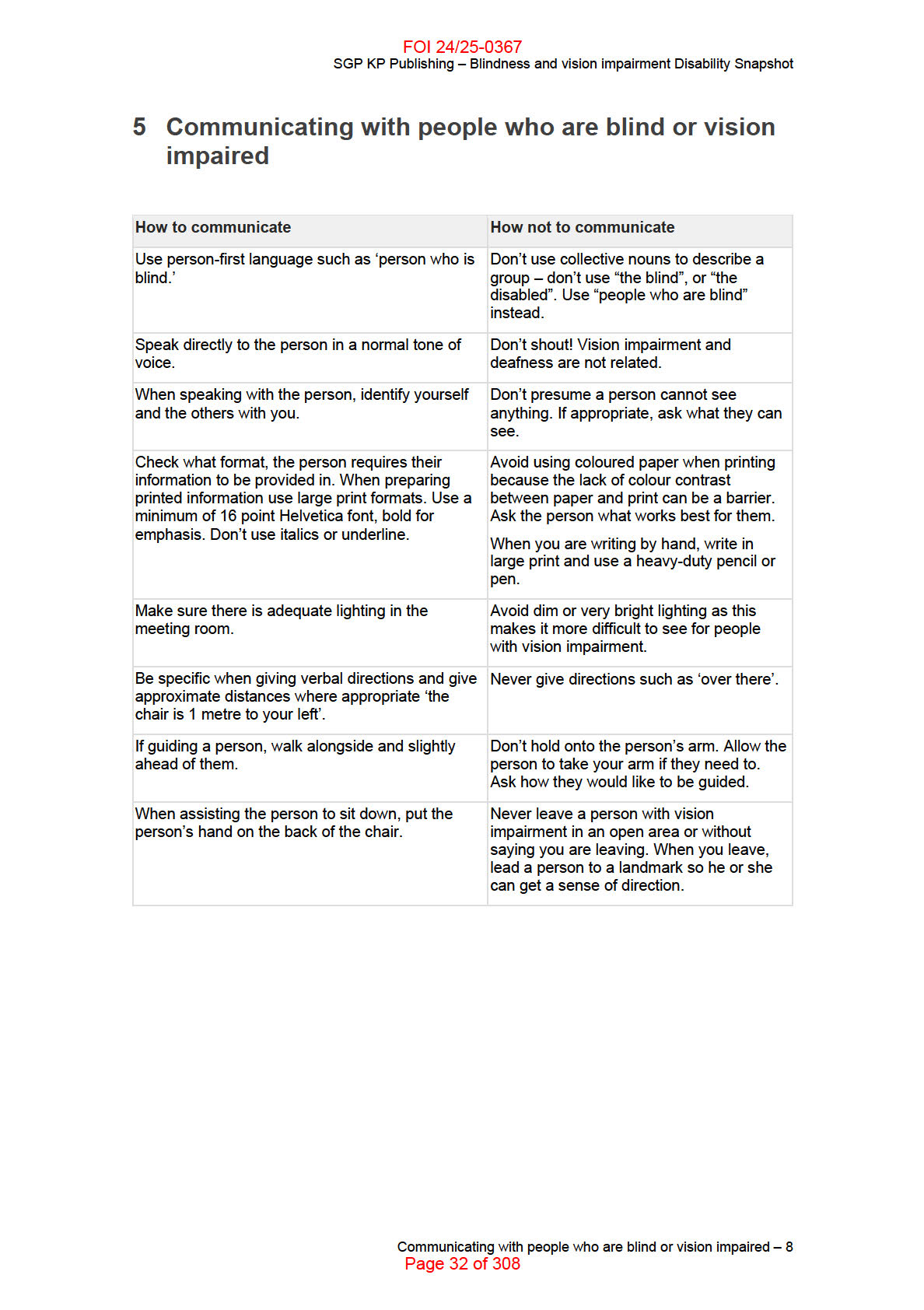

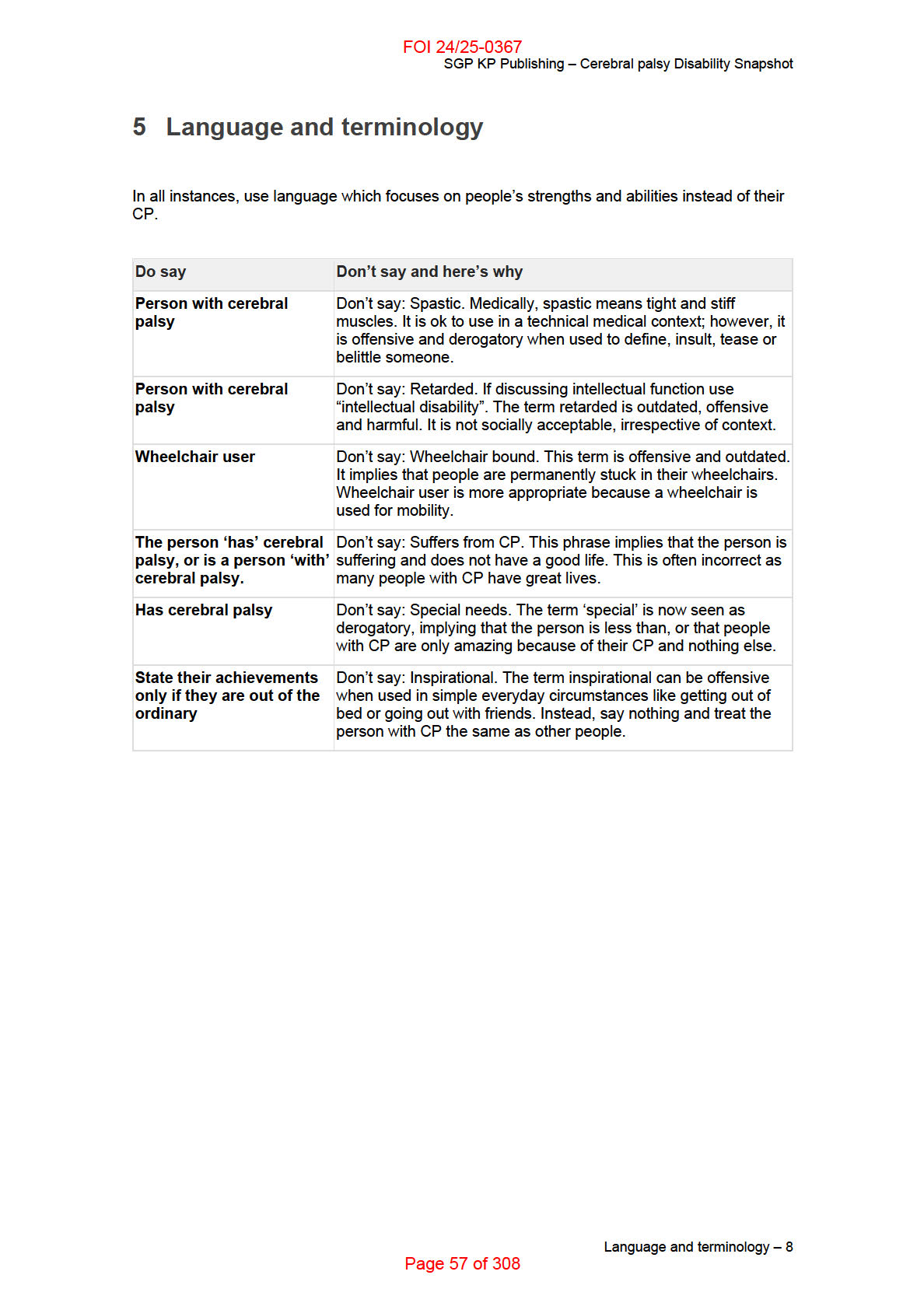

5 Language and terminology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

6 Enabling social and economic participation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

7 Families and carers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

8 How can I tailor a meeting to suit a participant with cerebral palsy?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

9 Peak body consulted . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

10

Helpful links . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Table of Contents – 2

Page 51 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Cerebral palsy Disability Snapshot

This Disability Snapshot provides general information about cerebral palsy to assist you in

communicating effectively and supporting the participant to develop their goals in a planning

meeting. Each person is an individual and wil have their own needs, preferences and

experiences that wil impact on the planning process. This information has been prepared for

NDIA staff and partners and is not intended for external distribution.

What is cerebral palsy? – 3

Page 52 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Cerebral palsy Disability Snapshot

1 What is cerebral palsy?

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a lifelong physical disability that begins in early childhood. It occurs in the

developing brain in pregnancy or in early childhood. It effects movement, posture, muscle

control and co-ordination of movement. Many people with CP may also have secondary

disabilities.

CP may change and its impact may become more complicated over time but it is not a

degenerative condition. CP is the most common physical disability in children. There are

currently around 34,000 people living with CP in Australia and 1 in 500 Australian babies are

diagnosed with the condition.

CP can affect gross and fine motor skil s, as well as speech. This impacts on participation in

everyday activities. Although CP is lifelong and non-progressive, factors such as puberty,

ageing and weight gain may detrimentally impact a person’s function.

Specialists such as paediatricians or neonatal specialists can diagnose CP. General

practitioners (GPs) also frequently play a critical role in maintaining the daily functioning and

wellbeing of someone with CP. The complexity of CP means interventions from a variety of

specialists and allied health professionals are usually required to support participation in

everyday activities.

What is cerebral palsy? – 4

Page 53 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Cerebral palsy Disability Snapshot

2 Different types and measures for describing cerebral

palsy

The different types of CP include spasticity, involuntary muscle movements (dyskinesis),

writhing or repetitive movements (athetosis or dystonia) and involuntary coordination of

movements (ataxia).

CP can affect people in different ways:

• quadriplegia where both upper and lower limbs are affected. Often the torso and head

are also affected

• diplegia where the lower limbs are affected. The upper limbs may be only slightly

affected

• hemiplegia where only one side of the body is affected.

The Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) is the most commonly used

measurement tool for describing the severity of CP. This system has a 1-5 rating scale, with 1

being the least severe and 5 being the most severe. The GMFCS classifies the level of a

person’s function in terms of their ability to perform gross motor actions, including sitting,

standing, walking and running.

Different types and measures for describing cerebral palsy – 5

Page 54 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Cerebral palsy Disability Snapshot

3 Common characteristics and impacts of cerebral

palsy

Although everyone with CP is different, there are some commonalities, including:

• Many people with CP have a second or third disability or associated impairments such

as intellectual disability (50%), epilepsy (25%), hearing or vision impairment (10%),

speech impairment (25%), behaviour disorder (25%), incontinence (25%), sleep

disorder (20%) and saliva control problems (20%).

• Some people with CP have a mental health condition. Anxiety and depression are

common. Reasons for this are not the underlying physical disorder but the associated

psychological and social factors that may impact the individual.

• Many people with CP experience chronic pain (75%), particularly in adulthood.

• Most people experience a significant decline in physical functioning in adulthood.

Exercise, stretching and therapy help people maintain their strength and function.

• People with CP can have muscle weakness.

These additional impairments can have a greater impact than the CP itself and wil require

higher levels of support to enable someone to engage in everyday life. For example, a person

who does not have good hand function and a speech impairment, wil likely need assistive

technology to help them to communicate effectively.

Common characteristics and impacts of cerebral palsy – 6

Page 55 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Cerebral palsy Disability Snapshot

4 Common misconceptions about cerebral palsy

• Most people with CP can walk with minimal support. In fact, some individuals mobilise

with little or no support so their disability may go unnoticed by others.

o The misconception is ‘everyone with CP uses a wheelchair or walking aid’.

• Intellectual disability only affects 50% of people with CP. Some people with mild CP

have an intellectual disability and some

o The misconception is ‘everyone with CP has an intellectual disability’.

• Approximately 10-30% of cases have a genetic component, with 1% being familial

(multiple siblings have CP).

o The misconception is ‘CP is not a genetic condition’.

• CP is not progressive or a life-limiting condition. In rare cases where a person has

profound CP, associated risk factors may reduce their life expectancy.

o The misconception is ‘everyone with CP has a limited life expectancy’.

• Most adults with CP can have regular sex. In some cases, physical limitations, societal

attitudes and other social barriers may present challenges to sexual activity.

o The misconception is ‘people with CP cannot be sexually active’.

• People with CP have the same reproductive systems as everyone else. Women with

CP can expect to have typical pregnancies.

o The misconception is ‘people with CP cannot have babies’.

• Non-verbal people with CP are most likely able to understand you. An inability to

communicate verbally does not mean the person has an intellectual disability.

o The misconception is ‘everyone who is non-verbal and has CP also has an

intellectual disability and cannot understand me’.

• Some people with CP may appear unsteady if they have uncoordinated, shaky, walking

patterns.

o The misconception is ‘a person with CP appears to be drunk’.

• Everyone has the right to full citizenship and inclusion.

o The misconception is ‘people with CP belong together and away from their

community’.

Common misconceptions about cerebral palsy – 7

Page 56 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Cerebral palsy Disability Snapshot

6 Enabling social and economic participation

It is important to explore how a person with CP can be supported to enable or maintain their

participation in mainstream activities, education and employment, taking into consideration their

interests and aspirations as an individual.

To enable and maintain work, ongoing supports or adjustments at work may be needed. This

might require NDIS funding for specialist disability or employment related assessment services.

Alternatively the person can access external employment retention and support initiatives such

as Work Assist provided by the Disability Employment Services (DES) program.

NDIS funding for personal care, assistance with travel or assistive technology may also be

required to support participation in the workforce.

If the person is preparing to enter the workforce, NDIS funded supports can assist people with

CP to build life skil s, capabilities and independence. Supports can be used to assist them

identify what their interests are and what work might be suitable. The supports can assist with

building specific work related skil s, manage barriers to work or develop a career plan.

Additionally, they can help prepare people with CP to connect with other government services

such as DES.

Enabling social and economic participation – 9

Page 58 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Cerebral palsy Disability Snapshot

7 Families and carers

Generally, the family of an individual with CP wil play a vital role in their physical, social and

emotional health for an extended period. A family’s ability to provide these supports wil vary

based on their own physical and mental health, work responsibilities, parenting capacity,

resilience and whether the parent has a disability themselves.

Family members of a person with CP are usually quite involved in providing direct support with

personal care, daily living, assistive technology, implementing therapy, teaching and supporting

communication, study and work, as well as attending medical and allied health appointments.

This is often beyond the age you would generally expect a parent or family member to provide

support.

Family members are often expected to advocate for their family member with CP, which is not

always possible. Family members may feel disempowered, exhausted and lacking in confidence

to challenge systemic barriers and mainstream services where supports are inadequate.

Supports including respite for family members can be critical to maintaining their own health and

wellbeing and allowing them to continue providing informal supports.

Supporting and considering holistic family needs, as well as other informal supports is important

when working with an individual with CP. This means the individual and those important to them

can function at their best.

Families and carers – 10

Page 59 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Cerebral palsy Disability Snapshot

8 How can I tailor a meeting to suit a participant with

cerebral palsy?

Every person with CP is unique and has different needs, wants, likes and dislikes. This means

people with CP wil have varied support requirements.

Before the meeting

• Ask if there are any accessibility requirements to consider.

• Check if the meeting place meets the participant’s needs. (For example, if the

participant is a wheelchair user the meeting place should have a ramp and/or elevator

and spacious disabled toilet with a railing).

• Consider the time of day and duration of the meeting. It can take a number of hours for

a person with CP to get up, dressed and ready to leave their home. Travel is also often

more complex.

• People with CP may require breaks during meetings. Some people become fatigued

easily and others with an intellectual disability may be overwhelmed with complex

information. Consider the length of the meeting and ask what time of day suits them

best.

• Ask the person if they require additional supports to understand information (such as

pictographs or sign language). Check if the person has a hearing or vision impairment

which may impact on how they need to receive information.

• Check to determine whether the participant wil be bringing an advocate or support

person with them.

• Provide as much information as possible about the purpose of the meeting ahead of

time, as they may need to discuss and prepare their responses with their support

person. People using a speech generating device to communicate may need to prepare

messages and store them in their device before the meeting.

• Provide any written material in plain English or Easy Read well before the meeting if

this is required.

Communication during the meeting

• It’s important to remember each person is different in their communication and the

support they might need. Approximately 25% of people with CP have challenges with

verbal communication. They may have sensory issues that affect their vision or hearing,

which may also affect their language and speech. They may have an intellectual

disability with difficulty in planning how to say complex sentences. People with CP may

have speech that is difficult to understand.

• When speaking, use appropriate volume and speed. Speak to the person directly and

observe how those known to the person communicate with them. Listen to the person

and clarify understanding.

• Check if the person has a personal communication system such as a communication

book, board, iPhone, iPad or speech generating device. If they do, ensure you give

them enough time to respond, ask questions and interact during the meeting.

• Don’t assume people who have communication difficulties have intellectual disabilities.

They may not use speech to communicate but may stil be able to understand

How can I tailor a meeting to suit a participant with cerebral palsy? – 11

Page 60 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Cerebral palsy Disability Snapshot

everything you say. When communicating with someone with CP where speech may be

affected, speak normally and use age appropriate language.

• If the person has an intellectual disability, use short sentences and provide pauses to

give the person enough time to hear and process what you are saying. Avoid using

jargon.

• If the person has speech which is difficult to understand, you may need to ask them to

repeat what they are saying. Speaking can require great effort for people with CP, so

repeat what you have understood so the person can concentrate on saying the part you

did not understand. If the person has repeated themselves several times and you are

stil unable to understand them, try alternative ways to communicate such as using a

gesture, communication board/device or pointing to an alphabet display.

• Speak as you usually would. Be aware it may take a while for someone to verbalise

what they want to say. Do not correct them or jump ahead or make assumptions about

what they are trying to say. Some people may use informal methods to communicate,

including facial expression, gestures, body language and behaviour.

• Understand some people may need more meetings to discuss everything.

How can I tailor a meeting to suit a participant with cerebral palsy? – 12

Page 61 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Cerebral palsy Disability Snapshot

9 Peak body consulted

The following organisations assisted in the development of this resource:

• Cerebral Palsy Support Network (members and staff)

• Cerebral Palsy Education Centre

• Members of the AusACPDM

• Melbourne Disability Institute

• The Royal Children's Hospital (Victoria)

• Centre of Research Excellence - CP

• Murdoch Children’s Research Institute

• Victorian Paediatric Rehabilitation Service

• CP Australia

• CP Al iance/Al iance Research Institute NSW

• CPL QLD

• Ability Centre WA

• Novita/Scosa SA

• Australian Catholic University.

Peak body consulted – 13

Page 62 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Cerebral palsy Disability Snapshot

10 Helpful links

• Cerebral Palsy Support Network

Helpful links – 14

Page 63 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

DOCUMENT 6

Deafblind Disability Snapshot

SGP KP Publishing

Exported on 2024-10-18 03:10:47

Page 64 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Deafblind Disability Snapshot

Table of Contents

1 Peak body consulted . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

2 What is deafblindness? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

3 How many people are deafblind? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

4 Types of deafblindness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

5 What are the characteristics of deafblindness? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

6 Psychosocial impact of deafblindness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

7 Communication . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

8 Enabling social and economic participation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

9 How can I tailor a meeting to suit a participant with deafblindness?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

10

Communication access and supports . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

11

Written communication . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

12

Aids and equipment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

13

Technology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

14

Helpful links . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Table of Contents – 2

Page 65 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Deafblind Disability Snapshot

This Disability Snapshot provides general information about deafblindness to assist you in

communicating effectively and supporting the participant to develop their goals in a planning

meeting. Each person is an individual and wil have their own needs, preferences and

experiences that wil impact on the planning process. This information has been prepared for

NDIA staff and partners and is not intended for external distribution.

Peak body consulted – 3

Page 66 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Deafblind Disability Snapshot

1 Peak body consulted

In developing this resource we consulted with the peak body representing people with this

disability, Deafblind Australia.

Peak body consulted – 4

Page 67 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Deafblind Disability Snapshot

2 What is deafblindness?

Deafblind is a term used when a person has a combination of both impaired vision and hearing.

Dual sensory loss or dual sensory impairment are other terms used to describe deafblindness.

Deafblindness is described as a unique and isolating sensory disability having both hearing and

vision loss or impairment. The disability can have a significant effect on communication,

socialising, connecting with others, mobility and daily living (Deafblind Australia, 2004).

A person with deafblindness may strongly identify with the blind culture or the deaf culture (or in

some cases, neither) as well as the culture of their family. An understanding of the complexity of

each person’s culture is important to respectfully establish communication, language and

learning.

What is deafblindness? – 5

Page 68 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Deafblind Disability Snapshot

3 How many people are deafblind?

• Studies have reported 0.2% to 3.3% of the population may be deafblind.

• In Australia nearly 100,000 people are reported to be deafblind and two-thirds of these

people are over the age of 65 years.

• One study reported 36% of individuals over the age of 85 years are deafblind.

How many people are deafblind? – 6

Page 69 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Deafblind Disability Snapshot

4 Types of deafblindness

Congenital deafblindness is a term used when a person is born deafblind or when their

combined hearing and vision impairment exists before any form of language or communication

has developed.

Congenital deafblindness can occur due to:

• hereditary or genetic conditions

• infection contracted by the mother during pregnancy

• disease

• infection or injury that affects a child early in their development.

Acquired deafblindness is a term used when a person:

• is born deaf or hard of hearing and later in life experience a deterioration in their vision

• has deafness or hearing impairment at birth and has vision impairment later in life

• is born with a vision impairment or blindness and has hearing loss later in life

• has vision and hearing that deteriorates at a later stage in their life through accident,

injury or disease

• experiences deafblindness through the ageing process.

Types of deafblindness – 7

Page 70 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Deafblind Disability Snapshot

5 What are the characteristics of deafblindness?

• A small number of people wil have no sight and no hearing.

• Other people who are deafblind wil have varying degrees of vision impairment and of

hearing impairment.

• Experiences and understanding of their world wil be different depending on whether a

person was born deafblind or if they acquired vision and hearing loss through

deterioration later in life.

• Becoming used to new environments and travelling independently and safely are

challenges.

• Communication is a key challenge for all people with deafblindness.

• Balance issues may affect some people with deafblindness, particularly those with

Usher Syndrome type 1. These balance issues can affect a person’s mobility.

What are the characteristics of deafblindness? – 8

Page 71 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Deafblind Disability Snapshot

6 Psychosocial impact of deafblindness

The impact of deafblindness on a person’s life wil vary. The impact on a person who has a

severe vision and hearing impairment can be significant.

Depression, anxiety, frustration, and boredom can occur from the isolation and other challenges

experienced by people with deafblindness. A person with this diagnosis may experience low

self-esteem and lack of confidence to move about independently and carry out daily tasks.

Psychosocial impact of deafblindness – 9

Page 72 of 308

FOI 24/25-0367 - DISCLOSURE LOG - DOCUMENTS

SGP KP Publishing – Deafblind Disability Snapshot

7 Communication

People with deafblindness are a very diverse group because of the varying degrees of their

vision and hearing impairments. Some people who are deafblind may also have other

disabilities. A wide range of communication methods might be used, including: