FOI 24/25- 0013

DOCUMENT 20

Research – Therapy Best Practice

In order to develop business rules for the funding of CB supports as part of the

Participant Budget Model, we need the following information:

• For the following disability groups: Parkinson’s Disease, multiple sclerosis,

muscular dystrophy, dementia, Huntington’s Disease, arthritis, chronic

fatigue, chronic pain, amputation.

• What is considered best practice in terms of:

a) The allied health team members of a multidisciplinary team, i.e. who

Brief

should be involved in managing the disability?

b) The frequency of intervention i.e. approximate dosage – how many

hours per year is required for each professional?

c) Evidence based practice for widely accepted therapy approaches. Not

too much detail required, mainly eg “For MS, X therapy approach is

often recommended, which involves intensive blocks of 20 sessions

every X months”. Looking for information again regarding number of

hours that would be considered best practice.

Date

28/06/21

s22(1)(a)(ii) - irre

Requester(s)

Jane

- Assistant Director (TAB)

Jean s22(1)(a)(ii)

- irrelev - Senior Technical Advisor (TAB)

Researcher

Jane s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelev - Research Team Leader (TAB)

Cleared

N/A

Please note:

The research and literature reviews col ated by our TAB Research Team are not to be shared external to the Branch. These

are for internal TAB use only and are intended to assist our advisors with their reasonable and necessary decision-making.

Delegates have access to a wide variety of comprehensive guidance material. If Delegates require further information on

access or planning matters they are to call the TAPS line for advice.

The Research Team are unable to ensure that the information listed below provides an accurate & up-to-date snapshot of

these matters.

The contents of this document are OFFICIAL

1 Contents

2 Summary ......................................................................................................................................... 2

3 Parkinson’s disease ......................................................................................................................... 3

3.1

Clinician involved in management .......................................................................................... 3

3.2

Best practice treatment and frequency of intervention ......................................................... 3

Page 179 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

4 Multiple sclerosis ............................................................................................................................ 4

4.1

Clinician involved in management .......................................................................................... 5

4.2

Best practice treatment and frequency of intervention ......................................................... 6

5 Muscular dystrophy ........................................................................................................................ 7

5.1

Clinician involved in management .......................................................................................... 7

5.2

Best practice treatment and frequency of intervention ......................................................... 8

6 Dementia ......................................................................................................................................... 9

6.1

Clinician involved in management .......................................................................................... 9

6.2

Best practice treatment and frequency of intervention ......................................................... 9

7 Huntington’s disease ..................................................................................................................... 11

7.1

Clinician involved in management ........................................................................................ 11

7.2

Best practice treatment and frequency of intervention ....................................................... 11

8 Arthritis ......................................................................................................................................... 13

9 Chronic fatigue syndrome ............................................................................................................. 14

9.1

Clinician involved in management ........................................................................................ 15

9.2

Best practice treatment and frequency of intervention ....................................................... 15

10

Chronic pain .............................................................................................................................. 16

11

Amputation ............................................................................................................................... 17

11.1 Clinician involved in management ........................................................................................ 17

11.2 Best practice treatment and frequency of intervention ....................................................... 18

12

References ................................................................................................................................ 20

2 Summary

• Information provided has been obtain from a rapid review of the literature. This includes

best practice guidelines, systematic reviews from the Cochrane Collaboration and other high

quality meta-analyses and reviews.

• The personal circumstances, goals of each individual, and severity of the disease impacts the

level of intervention required. Therefore, it is often not possible to provide an exact number

of hours required for each intervention. This is reflected in the literature as studies

investigating the same intervention often deliver it at a different frequency, leading to a lack

of agreement around gold standard levels.

• If the agency requires precise numbers around how many hours of intervention are useful

per clinician they will need to commission systematic reviews of each type of intervention

delivered, across various disease severities. This is a substantial tasks. Current literature

Page 180 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

focuses on the effectiveness rather than the intensity of intervention. The level of

intervention is often decided by the allied health professional looking after the patient.

3 Parkinson’s disease

3.1

Clinician involved in management

A systematic review and meta-analysis of integrated care in Parkinson’s disease provides a list of

core team members to be included in interventions [1].

• Movement disorders specialist

• General neurologist

• PD specialist nurse

• Physiotherapist

• Occupational therapist

• Speech therapist

• Clinical psychologist

• Neuropsychologist

• Community mental health team

• Social worker

• Dietician

Models of care varied significantly, ranging from 4-8 weeks, 1-4 sessions a day (30 minutes to 2 hr

per session) ranging from 1-7 days a week. No indication of what hours were al ocated to each

profession.

3.2

Best practice treatment and frequency of intervention

Recommendations for treatment are taken from the NICE UK guidelines [2].

1) First-line treatment

a. Offer levodopa to people in the early stages of Parkinson's disease whose motor

symptoms impact on their quality of life.

b. Consider a choice of dopamine agonists, levodopa or monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B)

inhibitors for people in the early stages of Parkinson's disease whose motor

symptoms do not impact on their quality of life.

2) Non-pharmacological management

a. Nurse specialist interventions

i. Clinical monitoring and medicines adjustment.

ii. A continuing point of contact for support, including home visits when

appropriate.

Page 181 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

iii. A reliable source of information about clinical and social matters of concern

to people with Parkinson's disease and their family members and their

carers (as appropriate).

b. Physiotherapy and physical activity [3]

i. General physiotherapy: 4 weeks to 12 months. Only 2 studies reported

duration of sessions which included 12 hrs over 4 weeks and 18 hrs over 6

weeks.

ii. Exercise: Treatment sessions lasted from 30 minutes to two hours, and took

place over a period of three to 24 weeks.

iii. Treadmill: Treatment sessions lasted from 30 to 60 minutes, and took place

over a period of four to eight weeks.

iv. Cueing: Treatment sessions lasted from four to 30 minutes and took place

over a period of a single session to 13 weeks.

v. Dance: Dance classes lasted one hour over 12 to 13 weeks, with a trained

instructor teaching participants the tango, waltz, or foxtrot.

vi. Martial arts: Treatment lasted one hour and took place over a period of 12

to 24 weeks

c. Speech and language therapy [4]

i. Median duration of therapy for those treated was four weeks with 68%

attending a single weekly session, a further 22%, who were predominantly

receiving Lee Silverman Voice Therapy (LSVT), had four or more therapy

sessions per week. Most sessions (80%) lasted between 30-60 minutes.

d. Occupational therapy [5]

i. A Cochrane Review from 2007 only found 2 studies that met inclusion

criteria. These studies delivered intervention of 12 hours across 4 weeks,

and 20 hours over 5 weeks.

e. Nutrition [6]

i. Monitoring every four to six weeks if there have been any changes to

medications or treatment plan, with particular focus on the swallowing

recommendations.

ii. Every three months if the patient’s condition is stable.

iii. For oral nutrition support, regular review of ONS prescriptions every three

months is advisable, to ensure the appropriateness of the intervention.

iv. Some centres offer one-day holistic reviews to re-assess mobility, swallow,

speech and nutritional status.

* Dysphagia management should be conducted by speech and language therapists in conjunction

with nurses and dietitians. No information provided on level/duration of intervention [7].

3) Deep brain stimulation

a. Surgery is performed to implant a device that sends electrical signals to brain areas

responsible for body movement. Electrodes are placed deep in the brain and are

connected to a stimulator device.

4 Multiple sclerosis

Page 182 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

4.1

Clinician involved in management

There is variation in the make-up of MS multidisciplinary teams. The NICE MS Clinical Guideline

states that: “As a minimum, the specialist neurological rehabilitation service should have as integral

members of its team, specialist [8, 9]:

• Doctors (GPs, Neurologist)

• Nurses

• Physiotherapists

• Occupational therapists

• Speech and language therapists

• Dieticians

• Continence specialists

• Clinical psychologists

• Ophthalmologist/orthoptist

• Social workers.

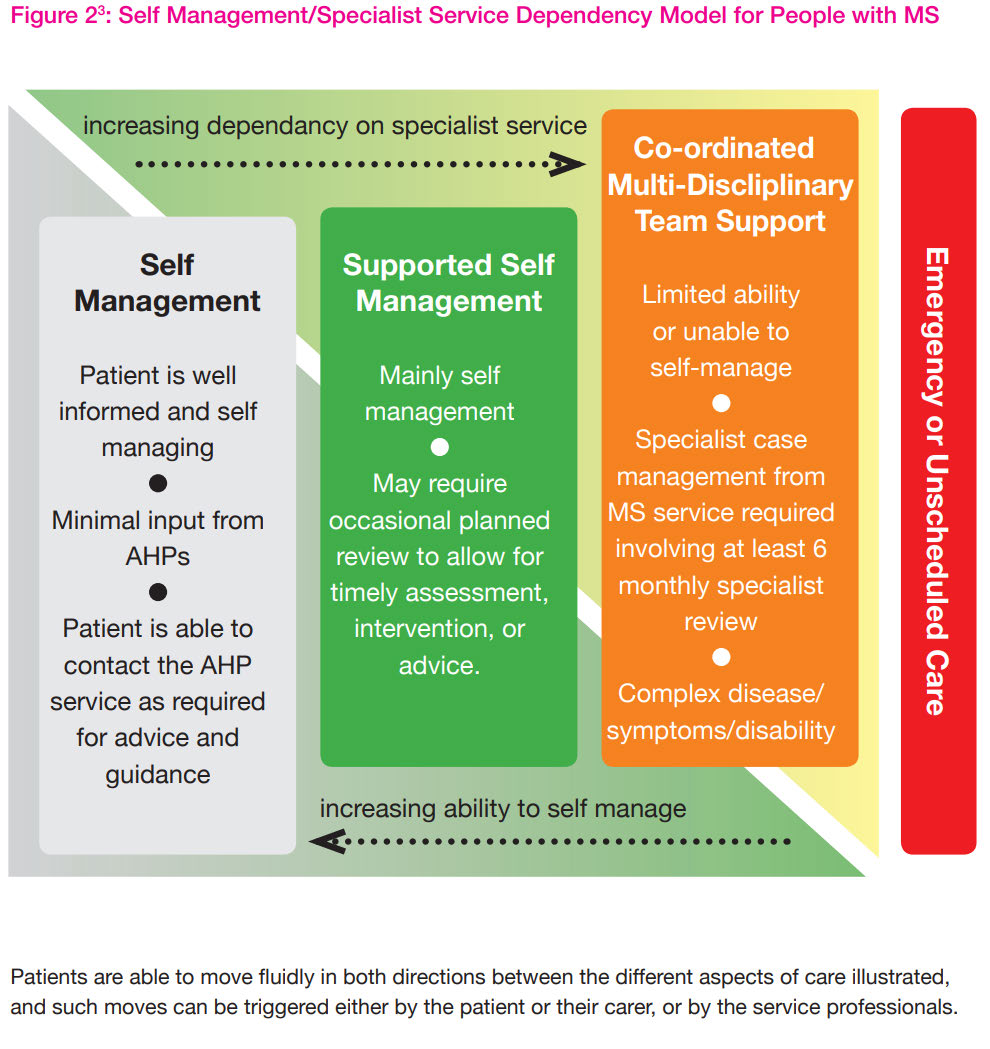

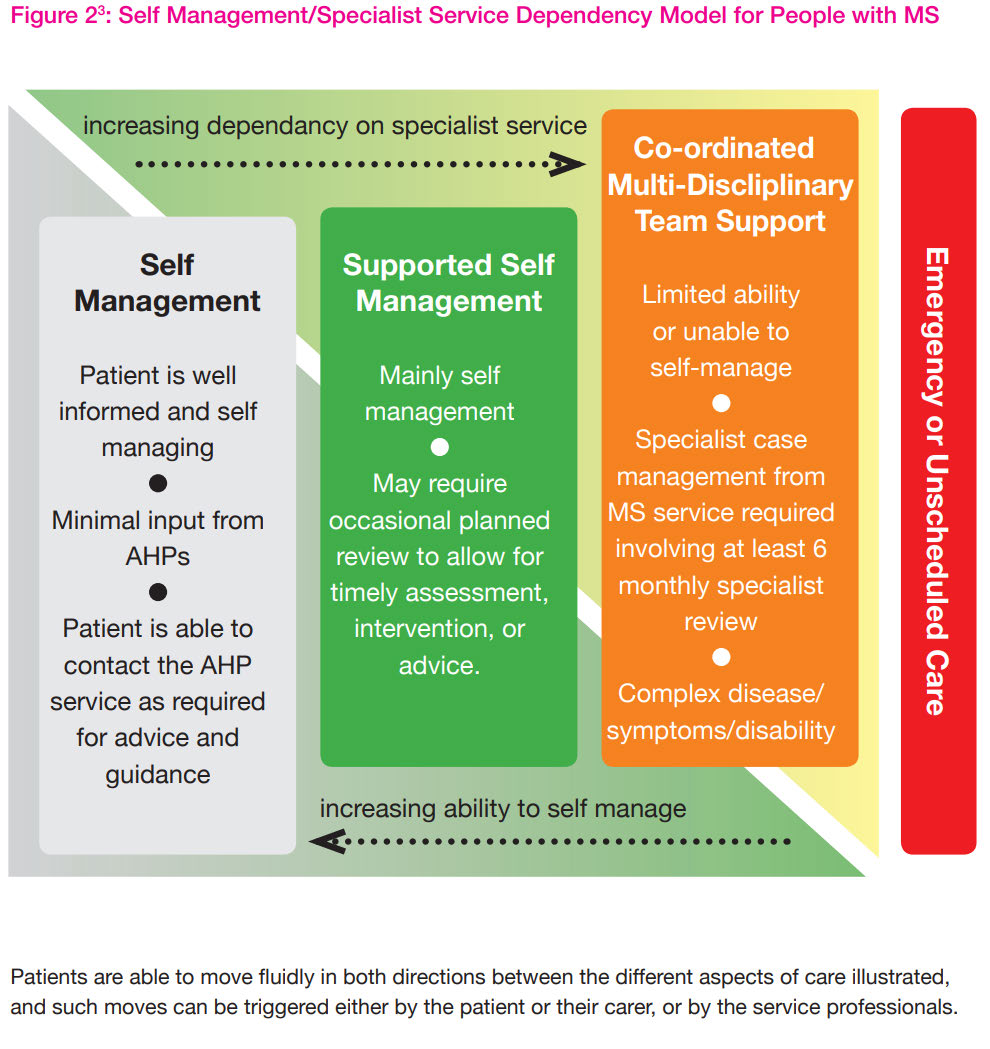

General rehabilitation – patients must be seen for 6-8 sessions or for a 6-8 week period, however,

appointments should be booked according to the needs of the patient [8]. The figure below

describes the level of dependency on specialist services for varying levels of disease severity.

Page 183 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

4.2

Best practice treatment and frequency of intervention

Determine how often the person with MS wil need to be seen based on [9]:

• Their needs, and those of their family and carers

• The frequency of visits needed for different types of treatment (such as review of disease-

modifying therapies, rehabilitation and symptom management).

o

“Review information, support and social care needs regularly”

The below interventions are listed in the NICE UK guidelines for the management of MS [9]

1) Exercise programs

2) Mindfulness-based training

3) Cognitive behavioural therapy

4) Fatigue management

5) Mobility rehabilitation

6) Spasticity management

Page 184 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

7) Occupational therapy – memory or cognitive problems

8) Diet

9) Ocular rehab

A Cochrane Review of Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation (MD) for the treatment of MS has been

conducted to determine its effectiveness [10]. The concept of MD comprises elements of physical

therapy, occupational therapy, speech pathology, psychology and or neuropsychology, cognitive

therapy and or behaviour management, social work, nutrition, orthotics, counsel ing input,

recreation and vocational therapy.

Intensity of MD rehabilitation programme was subdivided into 'high' or 'low' intensity

• High intensity therapy involved input from at least two disciplines, a minimum of thirty minutes

per session and total duration of at least 2-3 hours of interrupted therapy per day for at least 4

days per week. This is usual y provided in inpatient settings and some outpatient programmes.

• Low intensity programmes varied, the intensity and duration of therapy was lesser than that

provided in inpatient rehabilitation settings and was dependent upon the type of rehabilitation

setting and available resources

From this review, it has not been possible to suggest best 'dose' of therapy, further studies are

needed to suggest optimum number, duration and intensity of treatment sessions.

Neuropsychological rehabilitation

A Cochrane Review of neuropsychological rehabilitation (delivered by psychologists) for MS was

conducted in 2014 [11]. It found that the number of intervention sessions varied from eight to 36,

the duration of the rehabilitation intervention from four weeks to six months, and the frequency

from two times per month to five times per week. When analysing the results with regard to the

number of sessions, duration and frequency, no definite conclusions can be drawn about the effect

of these factors on rehabilitation outcomes.

Exercise

Ranging from 6 to 24 weeks in duration, ranging from once to 5 times weekly frequency [12].

5 Muscular dystrophy

5.1

Clinician involved in management

Muscular dystrophy (MD) is a group of diseases that cause progressive weakness and loss of muscle

mass. The most common form of MD is Duchenne’s MD which most commonly occurs in young

boys. The below wil be presented for Duchenne’s MD.

The care team should include a [13]:

• Neurologist with expertise in neuromuscular diseases

• Physical medicine and rehabilitation specialist

Page 185 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

• Physiotherapist

• Occupational therapists.

• Speech-language pathologists

• Orthotist

• Psychologist

• Dietician.

Some people might also need a lung specialist (pulmonologist), a heart specialist (cardiologist, a

sleep specialist, a specialist in the endocrine system (endocrinologist), an orthopedic surgeon and

other specialists.

5.2

Best practice treatment and frequency of intervention

Several types of therapy and assistive devices can improve the quality and sometimes the length of

life in people who have muscular dystrophy. Examples include [13]:

•

Range-of-motion and stretching exercises. Muscular dystrophy can restrict the flexibility and

mobility of joints. Limbs often draw inward and become fixed in that position. Range-of-

motion exercises can help to keep joints as flexible as possible.

•

Exercise. Low-impact aerobic exercise, such as walking and swimming, can help maintain

strength, mobility and general health. Some types of strengthening exercises also might be

helpful.

o Optimal exercise modality and intensity of exercise for people with a muscle disease

is still unclear. Large variation in frequency, duration and intensity exists within the

literature [14-16].

•

Braces. Braces can help keep muscles and tendons stretched and flexible, slowing the

progression of contractures. Braces can also aid mobility and function by providing support for

weakened muscles.

•

Mobility aids. Canes, walkers and wheelchairs can help maintain mobility and independence.

•

Psychosocial intervention

•

Gastrointestinal and nutritional management

Guidelines published for the diagnosis and management of Duchenne’s MD essentially states that

patients should be assessed/reviewed every 6 months by allied health professionals involved in their

multidisciplinary care [17].

There is no specific guidance on how many hours/visits are required for each rehabilitation

intervention or clinician.

“Provide direct treatment by physical and occupational therapists, and speech-language

pathologists, based on assessments and individualised to the patient.”

Page 186 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

The above also goes for psychological assessment and intervention. The number of visits will depend

on the patient’s current needs and ability to cope with their diagnosis.

6 Dementia

6.1

Clinician involved in management

The needs of people with dementia vary widely and tailoring care to each person’s circumstances

can be complex. A multidisciplinary approach in which different health professionals work together

is important [18].

A medical specialist is required to make a dementia diagnosis. These include:

• General physicians

• General practitioners

• Geriatricians

• Neurologists

• Psychiatrists

• Rehabilitation physicians

A number of different allied health professionals may be required at different points in time,

including but not limited to [19]:

• Audiologists

• Dentists

• Dietitians

• Occupational therapists

• Orthoptists

• Physiotherapists

• Podiatrists

• Psychologists

• Social workers

• Speech pathologists

Nurses and aged care workers are also involved in the care of patients with dementia.

6.2

Best practice treatment and frequency of intervention

Best practice care has been taken from the UK NICE guidelines on dementia [20]:

1) Person centred care

a. Involving people in decision making

b. Providing information

c. Advance care planning

2) Care coordination

a. Provide people living with dementia with a single named health or social care

professional who is responsible for coordinating their care.

3) Interventions to promote cognition, independence and wel being

Page 187 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

a. “Offer a range of activities to promote wellbeing that are tailored to the person's

preferences” – i.e. previous hobbies/interests

b. Cognitive Stimulation for mild to moderate dementia

i. Cochrane Review found that intervention ranged from 4 weeks to 24

months [21]. Median session length across the studies was 45 minutes, and

the median frequency was three times a week, ranging from one to five

times a week. The total possible exposure to the intervention varied

dramatically, from 10 to 12 hours to 375 hours in the two-year study. Across

the 15 studies, the median exposure time was 30 hours.

c. Group reminiscence therapy for mild to moderate dementia

i. Cochrane Review concluded that duration and frequency of the sessions

could differed. Sessions ranged from 2-8 times at either 1-2 hours (face to

face or telephone) and were delivered by occupational therapists, trained

recreation therapists [22].

d. Cognitive rehabilitation or occupational therapy for mild to moderate dementia

i. A Cochrane Review found that intervention duration ranged from 2 to 104

weeks. Sessions ranged from 1-12 per week. More intense was classified as

more than 3 formal sessions per week. Duration was 30 to 240 minutes.

Those in day care facilities were often longer [23].

NOTE: The Cochrane Col aboration have undertaken various reviews of non-pharmacological

interventions for dementia and found that many lack convincing evidence or wel described

treatment protocols. These include homeopathy, acupuncture, aromatherapy, snoezelen, validation

therapy or dance movement therapy.

There is promising evidence that exercise programs may improve the ability to perform ADLs in

people with dementia, although some caution is advised in interpreting these findings. Included

studies were highly heterogeneous in terms of subtype and severity of participants' dementia, and

type, duration, and frequency of exercise [24].

4) Pharmacological interventions

a. acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine as

monotherapies are recommended as options for managing mild to moderate

disease

5) Caregiver education and skills training

a. A meta-analysis of 23 randomized clinical trials provides strong confirmation of the

benefits of caregiver education and skills training interventions for reducing

behavioural symptoms [19]. Collectively, these trials involved 3,279 community-

dwelling caregivers and patients. Effective interventions were wide-ranging and

included caregiver education, skills training (problem solving, communication

strategies), social support (linking caregivers to others), and/or environmental

modifications (assistive device use, creating a quiet uncluttered space).

Interventions varied in dose, intensity, and delivery mode (telephone, mail, face-to-

face, groups, computer technologies.

b. Successful interventions identified included approximately

nine to 12 sessions

tailored to the needs of the person with dementia and the caregiver and were

Page 188 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

delivered individual y in the home using multiple components

over 3–6 months with

periodic follow-up [19].

While pharmacological intervention can be conveniently packaged and standardised, with a

measured dose, non-pharmacological interventions can be more difficult to evaluate [25]. The same

intervention may be used in different studies, but it may comprise quite different components [25].

Non-pharmacological interventions have rarely used a standardised treatment manual; mainly due

to the range of individual differences between people with dementia [25].

Although some interventions can be offered for a discrete period of time, such as half an hour per

day, many others involve intervention at the level of the care setting or in the general approach or

interactive style of those providing care (i.e. depends on disease severity, level or care and care

providers) [25].

Frequency of intervention is briefly mentioned in the Australian Clinical Practice Guidelines and

Principles of Care for People with Dementia [18]. Statements include:

•

Health system planners should ensure that people with dementia have access to a care

coordinator who can work with them and their carer’s and families from the time of

diagnosis. If more than one service is involved in the person’s care, services should agree on

one provider as the person’s main contact, who is responsible for coordinating care across

services at whatever intensity is required.

• A care plan developed in partnership with the person and his or her carer(s) and family that

takes into account the changing needs of the person.

•

Formal reviews of the care plan at a frequency agreed between professionals involved and

the person with dementia and/or their carer(s) and family.

7 Huntington’s disease

7.1

Clinician involved in management

The multidisciplinary team assesses the stage of the disease and formulates, coordinates and

implements the individual care and treatment plan and consists of [26]:

• Physician

• Psychologist

• Speech and language therapist

• Social worker

• Occupational therapist

• Case manager

• Psychologist

• Dentist/oral health specialist

7.2

Best practice treatment and frequency of intervention

Page 189 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

Only non-pharmacological recommendations will be presented [27].

Motor Disorders

• Chorea

o Mouth guards splints.

o Physiotherapy, OT, speech intervention to assess protective measures.

• Dystonia

o Active and passive rehabilitation with a physiotherapist to maintain range of

movement.

• Rigidity

o Physiotherapy is recommended to improve or maintain mobility and prevent the

development of contractures and joint deformity.

• Swallowing disorders

o Motor skills training with speech therapist.

o Psychology for mood, behaviour, emotional status and cognition

o Provision of information and advice by a dietician, on food textures and consistency

and food modifications, bolus size and placement, safe swallowing procedures,

elimination of distractions and on focusing attention on just one task at a time can

help to avoid aspirations and leads to improvement of swallowing disorders.

• Gait and balance disorders

o Rehabilitative methods (e.g. physiotherapy and occupational therapy) may improve

walking and balance disorders and prevent from their main complications (falls,

fractures, loss of autonomy). Interventions for gait and balance should start as early

as possible and be continued and adapted throughout the progression of the

disease.

o Supervised low impact exercise.

• Manual dexterity

o Management with physiotherapy and occupational therapy may be useful to reduce

the functional impact of fine motor skill deterioration.

o OT may suggest adaptive aids to compensate for the deterioration of manual

dexterity (adapted cutlery, computer keyboard, adapted telephone, etc.)

• Global motor capacities

o Referral to a physiotherapist is recommended in order to facilitate the development

of a therapeutic relationship, promote sustainable exercise behaviours and ensure

long-term functional independence. Exercise programs should be personalized

(considering abilities and exercise capacity), goal directed and task specific.

• Cognition

o Multiple rehabilitation strategies (speech therapy, occupational therapy, cognitive

and psychomotricity) might improve or stabilise transitorily cognitive functions

(executive functions, memory, language.. ) at some point of time in the course of the

disease.

o Cognitive stimulation

• Language and communication disorders

o Communication disorders in HD are variable, requires comprehensive assessment of

language and of other factors such as mood, motivation and behaviour.

Page 190 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

o Multi-disciplinary input such as Speech & Language Therapy and Physiotherapy help

to retain communication and social interaction

o The changing communication needs of the person with HD wil be monitored and

reassessed throughout the course of the disease to plan effective management

strategies at all stages.

• Psychiatric disorders

o Based on data from other neurodegenerative conditions, mindfulness-based

cognitive therapy and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy may be useful.

o Underlying triggers causing changes in mood or behaviour should be addressed.

o The duration of treatment is generally for over 6 months and can be for several

years

*Unable to find precise data on frequency or duration of interventions for each professional.

8 Arthritis

The main treatment for arthritis is Methotrexate.

The NICE UK guidelines provides the below recommendations [28].

Non-pharmacological management

• Physiotherapy

o Adults with RA should have access to specialist physiotherapy, with periodic review

o Improve general fitness and encourage regular exercise

3 to 6 face to face sessions over 3-6 month period [29].

o Learn exercises for enhancing joint flexibility, muscle strength and managing other

functional impairments

o Learn about the short-term pain relief provided by methods such as transcutaneous

electrical nerve stimulators (TENS) and wax baths.

• Occupational therapy

o Adults with RA should have access to specialist occupational therapy, with periodic

review if they have:

Difficulties with any of their everyday activities, or

Problems with hand function.

• Hand exercise programmes

o Consider a tailored strengthening and stretching hand exercise programme for

adults with RA with pain and dysfunction of the hands or wrists if:

They are not on a drug regimen for RA, or

They have been on a stable drug regimen for RA for at least 3 months.

The tailored hand exercise programme for adults with RA should be delivered by a practitioner with

training and skills in this area.

• Podiatry

o All adults with RA and foot problems should have access to a podiatrist for

assessment and periodic review of their foot health needs.

Page 191 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

o Functional insoles and therapeutic footwear should be available for all adults with

RA if indicated.

• Psychological interventions

o Offer psychological interventions (for example, relaxation, stress management and

cognitive coping skills [such as managing negative thinking]) to help adults with RA

adjust to living with their condition.

o Meta-analysis of psychological interventions for arthritis pain found that

interventions tested were most commonly delivered in a total of nine sessions of 85

min duration, offered on a weekly or biweekly basis [30].

• Diet and complementary therapies

o Inform adults with RA who wish to experiment with their diet that there is no strong

evidence that their arthritis will benefit. However, they could be encouraged to

follow the principles of a Mediterranean diet (more bread, fruit, vegetables and fish;

less meat; and replace butter and cheese with products based on vegetable and

plant oils).

o Inform adults with RA who wish to try complementary therapies that although some

may provide short-term symptomatic benefit, there is little or no evidence for their

long-term efficacy.

o If an adult with RA decides to try complementary therapies, advise them: these

approaches should not replace conventional treatment.

Monitoring

Ensure that all adults with RA have:

• Rapid access to specialist care for flares

• Information about when and how to access specialist care, and

• Ongoing drug monitoring.

Consider a review appointment to take place

6 months after achieving treatment target (remission

or low disease activity) to ensure that the target has been maintained.

Offer all adults with RA, including those who have achieved the treatment target, an annual review

to:

o Assess disease activity and damage, and

o Measure functional ability (using, for example, the Health Assessment Questionnaire

[HAQ]).

o Check for the development of comorbidities, such as hypertension, ischaemic heart

disease, osteoporosis and depression.

o Assess symptoms that suggest complications, such as vasculitis and disease of the

cervical spine, lung or eyes.

o Organise appropriate cross referral within the multidisciplinary team.

9 Chronic fatigue syndrome

Page 192 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

9.1

Clinician involved in management

In most cases, a GP should be able to diagnose chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). However, if, after a

careful history, examination and screening investigations, the diagnosis remains uncertain, the

opinion of a specialist physician, adolescent physician or paediatrician should be sought [31].

Other non-medical professionals include:

• Physiotherapists

• Occupational therapists

• Psychologists

• Social workers

• Dieticians

9.2

Best practice treatment and frequency of intervention

Care should be provided to people with CFS using a coordinated multidisciplinary approach. Based

on the person’s needs, include health and social care professionals with expertise in the following

[31, 32]:

• self-management strategies, including energy management

• symptom management

• managing flares and relapse

• activities of daily living

• emotional wellbeing, including family and sexual relationships

• diet and nutrition

• mobility, avoiding falls and problems from loss of dexterity, including access to aids and

rehabilitation services

• social care and support

• support to engage in work, education, social activities and hobbies

No detailed information could be sourced around how many hours are required per clinician for

each of these approaches. It is clearly stated that service providers should be “adapting the timing,

length and frequency of all appointments to the person’s needs” [32].

There is still little evidence to support any particular management or intervention for CFS in primary

care that can provide an effective early intervention [33]. The only two evidence based therapies

recommended by NICE are:

• Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

o Five to 16 sessions. Sessions ranged from 30 minutes to 150 minutes [34]

o People with CFS should not undertake a physical activity or exercise programme

unless it is delivered or overseen by a physiotherapist or occupational therapist who

has training and expertise in CFS [32].

o

Page 193 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

• Exercise Therapy

o Duration of the exercise therapy regimen varied from 12 weeks to 26 weeks

o three and five times per week, with a target duration of 5 to 15 minutes per session

using different means of incrementation, often exercise at home [35]

10 Chronic pain

This is a very broad area. Treatments depend on location of pain. Musculoskeletal pain, particularly

related to joints and the back, is the most common single type of chronic pain.

Information provided in the section on arthritis directly relates to the management of chronic pain.

A substantial systematic review by Skelly, Chou [36] investigated non-pharmacological interventions

for chronic pain. Interventions that improved function and/or pain for ≥1 month included:

• Low back pain:

o Exercise

o Psychological therapy

o Spinal manipulation

o Low-level laser therapy

o Massage

o Mindfulness-based stress reduction

o Yoga

o Acupuncture

o Multidisciplinary rehabilitation

• Neck pain

o Exercise

o Low-level laser

o Mind-body practices

o Massage

o Acupuncture

• Knee osteoarthritis

o Exercise

o CBT

• Hip osteoarthritis

o Exercise

o Manual therapies

• Fibromyalgia

o Exercise

o CBT

o Myofascial release massage

o Mindfulness practices

o Acupuncture

Page 194 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

Substantial variability in the numbers of sessions, length of sessions, duration of treatment, methods

of delivering the interventions and the experience and training of those providing the interventions

present a challenge to assessing applicability [36].

The range and duration of sessions of interventions are provided below.

• Psychological therapy sessions ranged from six to eight, and the duration of therapy ranged

from 6 to 8 weeks

• Exercise therapy ranged from 6 weeks to 12 months, and the number of supervised exercise

sessions ranged from 3 to 52.

• Ultrasound therapy was 4 and 8 weeks and the number of sessions was 6 and 10.

• Laser therapy ranged from 2 to 6 weeks and the number of sessions ranged from 10 to 12.

• Manipulation therapy sessions ranged from 4 to 24 and the duration of therapy ranged from

4 to 12 weeks.

• Massage therapy ranged from 2 to 10 weeks and the number of massage sessions ranged

from 4 to 24

• Mindfulness based stress reduction 1.5 to 2 hour weekly group sessions for 8 weeks.

• Yoga therapy ranged from 4 to 24 weeks and the number of sessions ranged from 4 to 48.

• Acupuncture therapy ranged from 6 to 12 weeks and the number of acupuncture sessions

ranged from 6 to 15.

• Relaxation training and muscle performance exercise therapy were done in 30-minute

sessions three times per week for 12 weeks,

11 Amputation

11.1

Clinician involved in management

The Limbs 4 Life is the peak body for amputees in Australia. They provide a list of professionals who

assist with rehabilitation of amputees [37].

• Rehabilitation Consultant (doctor)

o Oversees and coordinates medical care.

• Occupational Therapist

o Helps adjust to day to day activities like: personal care, domestic tasks such as: meal

preparation, accessing your place of residence, driving, education or work readiness.

If you are an upper limb amputee the occupational therapist will assist you to set

goals, teach you how to perform tasks, explore modifications required to achieve

goals (e.g. changes within the home or workplace), explore equipment to assist with

completing tasks and assist you with the functional training of your prosthesis.

• Physiotherapist

o Design a tailored exercise program tailored. They will assist with balance, flexibility,

strength and stamina. They will help with mobility aids such as: wheelchairs, walking

frames, crutches and other assistive devices.

• Prosthetist

Page 195 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

o Will look after the design, manufacture, supply and fit of the prosthesis. Together,

you wil discuss and decide on the prosthetic components to suit your needs and

lifestyle.

• Psychologist

o Supports individuals and fosters positive mental health outcomes and personal

growth.

• Nursing team

o Assists with your medications, personal hygiene, bathing and dressing and any

wound care and diabetic management that is required.

• Dietitian

• Podiatrist

11.2

Best practice treatment and frequency of intervention

Physiotherapy

The physiotherapist progresses the patient through a programme based on continuous assessment

and evaluation [38]. Through regular assessment, the physiotherapist should identify when the

individual has achieved optimum function with a prosthesis, facilitating discharge to a maintenance

programme.

The consensus opinion is that the physiotherapist should contribute to the management of wounds,

scars, residual limb pain and phantom pain and sensation together with other members of the

multidisciplinary team [38].

During prosthetic rehabilitation

patients should receive physiotherapy as often as their needs and

circumstances dictate [38].

Occupational therapy

The occupational therapy practitioner provides critical interventions, such as [39]”

• identifying the client’s functional goals, which can include self-care, home management, work

tasks, driving, child care, and leisure activities, and offering modifications to complete these

goals if required

• analysing tasks and providing modifications to achieve functional goals

• providing education on compensatory techniques and equipment to accomplish tasks and

activities

• providing prosthetic training

• identifying and addressing psychosocial issues

Occupational therapy intervention wil vary according to individual needs, and phases of intervention

may overlap, depending on the person’s progress [39].

The administration of interventions for phantom limb have been shown to range between one day

and 12 weeks, with one to five sessions per week [40] .

Page 196 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

Psychology

Counselling and psychological support is available to the person and their valued others

preoperatively and continues as part of lifelong management [41].

Experienced clinical counselling and psychological support should be available to assist with issues

such as adjustment and pain management from the acute phase, and throughout lifelong

management [41].

Psychosocial issues are evaluated and addressed as part of the overall treatment plan and reviewed

regularly throughout the care journey [41].

No information could be sourced about how many sessions are required.

Page 197 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

12 References

1.

Rajan R, Brennan L, Bloem BR, Dahodwala N, Gardner J, Goldman JG, et al. Integrated Care in

Parkinson's Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Movement Disorders [Internet]. 2020

2020/09/01; 35(9):[1509-31 pp.]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.28097.

2.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Parkinson’s disease in adults. 2017.

Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng71/resources/parkinsons-disease-in-adults-

pdf-1837629189061.

3.

Tomlinson CL, Patel S, Meek C, Herd CP, Clarke CE, Stowe R, et al. Physiotherapy versus

placebo or no intervention in Parkinson's disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

[Internet]. 2013; (9). Available from: https://doi.org//10.1002/14651858.CD002817.pub4.

4.

Herd CP, Tomlinson CL, Deane KHO, Brady MC, Smith CH, Sackley CM, et al. Speech and

language therapy versus placebo or no intervention for speech problems in Parkinson's disease.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2012; (8). Available from:

https://doi.org//10.1002/14651858.CD002812.pub2.

5.

Dixon L, Duncan DC, Johnson P, Kirkby L, O'Connel H, Taylor HJ, et al. Occupational therapy

for patients with Parkinson's disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2007; (3).

Available from: https://doi.org//10.1002/14651858.CD002813.pub2.

6.

The Association of UK Dieticians. Best practice guidance for dietitians on the nutritional

management of Parkinson’s. 2021. Available from:

https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021-

02/Best%20practice%20guidance%20for%20dietitians%20on%20the%20nutritional%20management

%20of%20Parkinson%27s%20FINAL.pdf.

7.

Deane K, Whurr R, Clarke CE, Playford ED, Ben-Shlomo Y. Non-pharmacological therapies for

dysphagia in Parkinson's disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2001; (1).

Available from: https://doi.org//10.1002/14651858.CD002816.

8.

Dix K, Green H. Defining the value of Allied Health Professionals with expertise in Multiple

Sclerosis. 2013. Available from: https://support.mstrust.org.uk/file/defining-the-value-AHPs.pdf.

9.

(NICE) NIfHaCE. Multiple sclerosis in adults: management. 2019. Available from:

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg186/resources/multiple-sclerosis-in-adults-management-pdf-

35109816059077.

10.

Khan F, Turner-Stokes L, Ng L, Kilpatrick T, Amatya B. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for

adults with multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2007; (2).

Available from: https://doi.org//10.1002/14651858.CD006036.pub2.

11.

Rosti-Otajärvi EM, Hämäläinen PI. Neuropsychological rehabilitation for multiple sclerosis.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2014; (2). Available from:

https://doi.org//10.1002/14651858.CD009131.pub3.

Page 198 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

12.

Hayes S, Galvin R, Kennedy C, Finlayson M, McGuigan C, Walsh CD, et al. Interventions for

preventing falls in people with multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

[Internet]. 2019; (11). Available from: https://doi.org//10.1002/14651858.CD012475.pub2.

13.

Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Muscular Dystrophy 2021 [Available

from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/muscular-dystrophy/symptoms-causes/syc-

20375388.

14.

Voet NBM, van der Kooi EL, van Engelen BGM, Geurts ACH. Strength training and aerobic

exercise training for muscle disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2019;

(12). Available from: https://doi.org//10.1002/14651858.CD003907.pub5.

15.

Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, Alman BA, Apkon SD, Blackwell A, et al. Diagnosis and

management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and

orthopaedic management. The Lancet Neurology [Internet]. 2018 2018/04/01/; 17(4):[347-61 pp.].

Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1474442218300255.

16.

Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, Apkon SD, Blackwell A, Colvin MK, et al. Diagnosis and

management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 3: primary care, emergency management,

psychosocial care, and transitions of care across the lifespan. The Lancet Neurology [Internet]. 2018

2018/05/01/; 17(5):[445-55 pp.]. Available from:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1474442218300267.

17.

Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, Apkon SD, Blackwell A, Brumbaugh D, et al. Diagnosis and

management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and neuromuscular, rehabilitation,

endocrine, and gastrointestinal and nutritional management. The Lancet Neurology [Internet]. 2018

2018/03/01/; 17(3):[251-67 pp.]. Available from:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1474442218300243.

18.

Guideline Adaptation Committee. Clinical Practice Guidelines and Principles of Care for

People with Dementia. Sydney: Guideline Adaptation Committee; 2016. Available from:

https://cdpc.sydney.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/CDPC-Dementia-Guidelines WEB.pdf.

19.

Brodaty H, Arasaratnam C. Meta-Analysis of Nonpharmacological Interventions for

Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Dementia. American Journal of Psychiatry [Internet]. 2012

2012/09/01; 169(9):[946-53 pp.]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11101529.

20.

National Institute for Health Care Excellence. National Institute for Health and Care

Excellence: Clinical Guidelines. Dementia: Assessment, management and support for people living

with dementia and their carers. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK)

Copyright © NICE 2018.; 2018.

21.

Woods B, Aguirre E, Spector AE, Orrell M. Cognitive stimulation to improve cognitive

functioning in people with dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2012; (2).

Available from: https://doi.org//10.1002/14651858.CD005562.pub2.

22.

Möhler R, Renom A, Renom H, Meyer G. Personally tailored activities for improving

psychosocial outcomes for people with dementia in community settings. Cochrane Database of

Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2020; (8). Available from:

https://doi.org//10.1002/14651858.CD010515.pub2.

23.

Bahar-Fuchs A, Martyr A, Goh AMY, Sabates J, Clare L. Cognitive training for people with mild

to moderate dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019(3).

24.

Forbes D, Forbes SC, Blake CM, Thiessen EJ, Forbes S. Exercise programs for people with

dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2015; (4). Available from:

https://doi.org//10.1002/14651858.CD006489.pub4.

Page 199 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

25.

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Dementia: A NICE-SCIE guideline on

supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care: British Psychological

Society; 2007. Dementia. 2014.

26.

Veenhuizen RB, Kootstra B, Vink W, Posthumus J, van Bekkum P, Zijlstra M, et al.

Coordinated multidisciplinary care for ambulatory Huntington's disease patients. Evaluation of 18

months of implementation. Orphanet J Rare Dis [Internet]. 2011; 6:[77- pp.]. Available from:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3253686/.

27.

Bachoud-Lévi A-C, Ferreira J, Massart R, Youssov K, Rosser A, Busse M, et al. International

Guidelines for the Treatment of Huntington's Disease. Frontiers in Neurology [Internet]. 2019 2019-

July-03; 10(710). Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fneur.2019.00710.

28.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Rheumatoid arthritis in adults:

management. 2018.

29.

Peter WF, Swart NM, Meerhoff GA, Vliet Vlieland TPM. Clinical Practice Guideline for

Physical Therapist Management of People With Rheumatoid Arthritis. Physical Therapy [Internet].

2021. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzab127.

30.

Dixon KE, Keefe FJ, Scipio CD, Perri LM, Abernethy AP. Psychological interventions for

arthritis pain management in adults: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology [Internet]. 2007; 26(3):[241-

50 pp.].

31.

Working Group of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians. Chronic fatigue syndrome.

Clinical practice guidelines--2002. Med J Aust [Internet]. 2002 May 6; 176(S9):[S17-s55 pp.].

32.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Myalgic encephalomyelitis (or

encephalopathy)/chronic fatigue syndrome: diagnosis and management. 2020. Available from:

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/gid-ng10091/documents/draft-guideline.

33.

Hughes JL. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Occupational Disruption in Primary Care: Is There

a Role for Occupational Therapy? British Journal of Occupational Therapy [Internet]. 2009

2009/01/01; 72(1):[2-10 pp.]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/030802260907200102.

34.

Price JR, Mitchell E, Tidy E, Hunot V. Cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic fatigue

syndrome in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2008; (3). Available from:

https://doi.org//10.1002/14651858.CD001027.pub2.

35.

Larun L, Brurberg KG, Odgaard-Jensen J, Price JR. Exercise therapy for chronic fatigue

syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2019; (10). Available from:

https://doi.org//10.1002/14651858.CD003200.pub8.

36.

Skelly AC, Chou R, Dettori JR, Turner JA, Friedly JL, Rundell SD, et al. Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality: Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. 2020. In: Noninvasive

Nonpharmacological Treatment for Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review Update [Internet]. Rockville

(MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). Available from:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556229/.

37.

Limbs 4 Life. Your recovery 2021 [Available from: https://www.limbs4life.org.au/steps-to-

recovery/your-rehabilitation-team.

38.

Broomhead P, Dawes D, Hale C, Lambert A, Quinlivan D, Shepherd R. Evidence based clinical

guidelines for the physiotherapy management of adults with lower limb prostheses. British

Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Amputation Rehabilitation; 2003. Available from:

https://docuri.com/download/csp-guideline-bacpar 59c1cb4df581710b2860eb11 pdf.

39.

Gulick K. The occupational therapy role in rehabilitation for the person with an upper-limb

amputation. American Occupational Therapy Association [Internet]. 2007. Available from:

Page 200 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

https://www.aota.org/About-Occupational-Therapy/Professionals/RDP/upper-limb-

amputation.aspx.

40.

Othman R, Mani R, Krishnamurthy I, Jayakaran P. Non-pharmacological management of

phantom limb pain in lower limb amputation: a systematic review. Physical Therapy Reviews

[Internet]. 2018 2018/03/04; 23(2):[88-98 pp.]. Available from:

https://doi.org/10.1080/10833196.2017.1412789.

41.

Innovation AfC. ACI Care of the Person following Amputation: Minimum Standards of Care.

Australia; 2017. Available from:

https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/ data/assets/pdf file/0019/360532/The-care-of-the-person-

following-amputation-minimum-standards-of-care.pdf.

Page 201 of 425