FOI 24/25-0473

DOCUMENT 2

Research Request – NAPA Therapy

• Is intensive therapy (i.e. NAPA) effective and beneficial/will it lead to

substantial functional improvement/increase independence in task when

compared to other therapeutic approaches?

• For children/participants with a disability

from birth and those that

acquire

injury is there an upper age limit at which further significant

improvement/gain from intensive therapy will taper off/cease?

• What sorts of benefits can be achieved (or are claimed) through NAPA

therapy and as compared to conventional therapy (traditional

weekly/fortnightly programs)?

• How do NAPA conduct therapy: is it collaborative within disciplines or are

participant’s still receiving one on one discipline specific therapy?

• What level of therapy is needed to maintain results/are results maintained

Brief

over the long term?

• Are intensive suitable for adults?

• Is intensive therapy suitable for people with attention/fatigue or cognitive

issues (can they focus for duration of intensive 4-5hours, 5 days x 3 weeks

~60-75hours of therapy)

• Effectiveness in home program uptake from intensives v traditional

therapy?

• What indicators used to determine when person has reached their maximal

level of function and plateau?

• What are the strengths and weaknesses of the NAPA approach to skil s

acquisition, as compared to other forms of therapy?

• What guidelines are available to evaluate or determine when NAPA may be

an appropriate approach?

Date

26/11/2020

Julie s22(1)(a)(ii) (

- irrelev

S enior Technical Advisor – TAB)

Requester Katrin s22(1)(a)(ii) - irre (A ssistant Director – TAB)

Researcher Jane s22(1)(a)(ii) - irreleva(R esearch Team Leader - TAB)

Cleared by Jane s22(1)(a)(ii) - irreleva(R esearch Team Leader - TAB)

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

1

Page 30 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

Contents

Key points ................................................................................................................................................ 3

What is NAPA? ........................................................................................................................................ 4

Intensive therapy .................................................................................................................................... 4

Difference between intensive therapy as described in the literature and NAPA therapy ................. 5

Suit therapy ............................................................................................................................................. 6

Cuevas Medek Exercise ........................................................................................................................... 8

Home based programs ............................................................................................................................ 9

Neuroplasticity and Gross Motor Function Classification Scores ......................................................... 10

Progressive disorders ............................................................................................................................ 14

Congenital neuromuscular disorders ................................................................................................ 14

Physical therapy interventions...................................................................................................... 15

Neurodegenerative Disorders in Childhood ..................................................................................... 15

Reference List ........................................................................................................................................ 30

Please note:

The research and literature reviews col ated by our TAB Research Team are not to be shared

external to the Branch. These are for internal TAB use only and are intended to assist our advisors

with their reasonable and necessary decision making.

Delegates have access to a wide variety of comprehensive guidance material. If Delegates require

further information on access or planning matters they are to call the TAPS line for advice.

The Research Team are unable to ensure that the information listed below provides an accurate &

up-to-date snapshot of these matters

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

2

Page 31 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

Key points

The NAPA centre does not provide any guidelines or specifics around how they determine which

interventions are delivered during their “intensive model of therapy,” or how they’re implemented

(multidisciplinary or individual therapists?). The centre promotes that its therapy is “highly effective”

and “cutting edge”, but without any protocols or published evidence to substantiate these claims it

is near impossible to determine whether the program is effective and beneficial. Without any

published evidence we can’t know:

a) Which diagnosis or ages this intervention is suitable for

b) What the long term results are or adverse effects (if any)

c) What the appropriate dosage/intensity is, or

d) When the patient has reached their maximal level of function

Based on the information provided on the NAPA website it is clear that the Therasuit, SpiderCage

and Cuevas Medek Exercises are the key interventions delivered during the intensive program.

Current literature does not support these interventions as best practice for cerebral palsy or ‘other’

neurological conditions.

There are intensive interventions (delivered >3 times a week) for cerebral palsy that are supported

by the literature. These include resistance/strength training and interventions for upper limb

function such as Constraint Induced Movement Therapy and Bimanual Training. However, these can

be delivered in a patient’s home or normal environment which makes them highly feasible (and

likely cost effective) – rather than attending a clinic for 2-6 hours a day or 3 weeks. Furthermore,

systematic reviews comparing conventional therapy (1-2 times a week) to more intensive

intervention have reported no clinically meaningful difference.

It is not clear from the NAPA website how patients are fol owed up after their intensive model of

therapy or whether home programs are developed to consolidate any improvements. This is of

concern given that home based programs have been shown in the literature to be highly beneficial.

The NAPA centre does offer weekly therapy sessions (1 hr) with physiotherapists, occupational

therapists and speech pathologists, however, this would only be appropriate for those who live in

Sydney, and it is unclear whether these weekly sessions consist of conventional/best practice

therapy or those delivered in the intensive model.

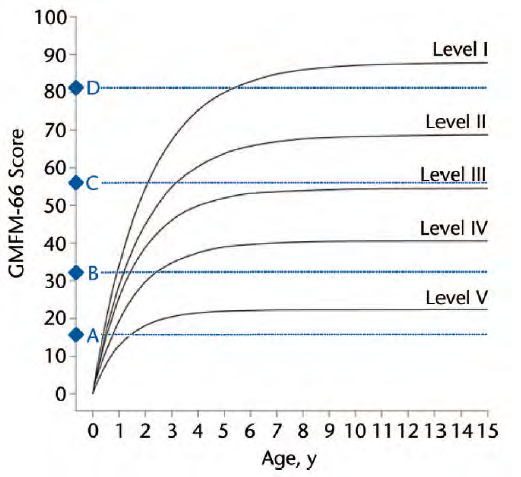

Information is provided within the document on neuroplasticity and motor function curves for

children with CP. These enable prognosis of gross motor progress across all 5 levels of Gross Motor

Function Classification System levels for ages 0 to 15.

Research update (05/03/2021)

A single systematic review and meta-analysis on garment/suit therapy has been added to the

literature review. The findings of this study do not change the advice/outcomes of the original

research document. Wells, Marquez [1] concluded

“Whilst there is some evidence for the use of

garment therapy it is not sufficiently robust to recommend the prescription of garment therapy

instead of, or as an adjunct to conventional therapy options”.

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

3

Page 32 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

What is NAPA?

The Neurological and Physical Abilitation or “NAPA” centre uses what they cal the ‘Intensive Model

of Therapy’ (IMOT) when treating children with cerebral palsy (CP) and ‘other’ neurological

disorders. Programs are customised for each patient and vary in time, duration, intensity and tools

used. The program usually consists of 2-6 hours of treatment a day, 5 days a week over 3 weeks. This

wil depend on diagnosis, age, stamina, strengths/weaknesses, and ‘other’ factors.

The core interventions used are the NeuroSuit and Multifunctional Therapy Unit (SpiderCage) in the

intensive therapy programs on children of all ages starting as young as age three. In addition,

therapists deliver Cuevas Medek Exercise (CME).

It is claimed that their methods are

“highly effective” and

“children often advance to the next

developmental skil or higher during the three-week program. For example, if a child is using a

walker, it is not uncommon for them to gain the strength, balance and ability to walk with crutches.”

The centre also provides

• Weekly therapy - available for physiotherapy, CME/MEDEK, occupational

therapy, NeuroSuit (min. 2 hours), and speech therapy.

Fortnightly appointments are not

available.

• VitalStim swallowing therapy

• Developmental feeding therapy

• Speech therapy

• Telehealth – only available to patients with current therapy authorisation with NAPA are

eligible

Intensive therapy

Intensive interventions for children with CP refers to the frequency and amount of training, the

duration of the training session (minutes or hours), and the duration of the training period (weeks or

months). [2, 3] The typical frequency of physical therapy for children with CP in an outpatient setting

is not well documented, however, physiotherapy sessions are typically offered 1-2 times per week to

young children with CP as reported in Norway, Canada and the US. [2, 4] Various studies

investigating intensive therapy/training have typically considered 3 or more sessions per week to

constitute ‘intensive’ compared to conventional treatment. [2, 5]

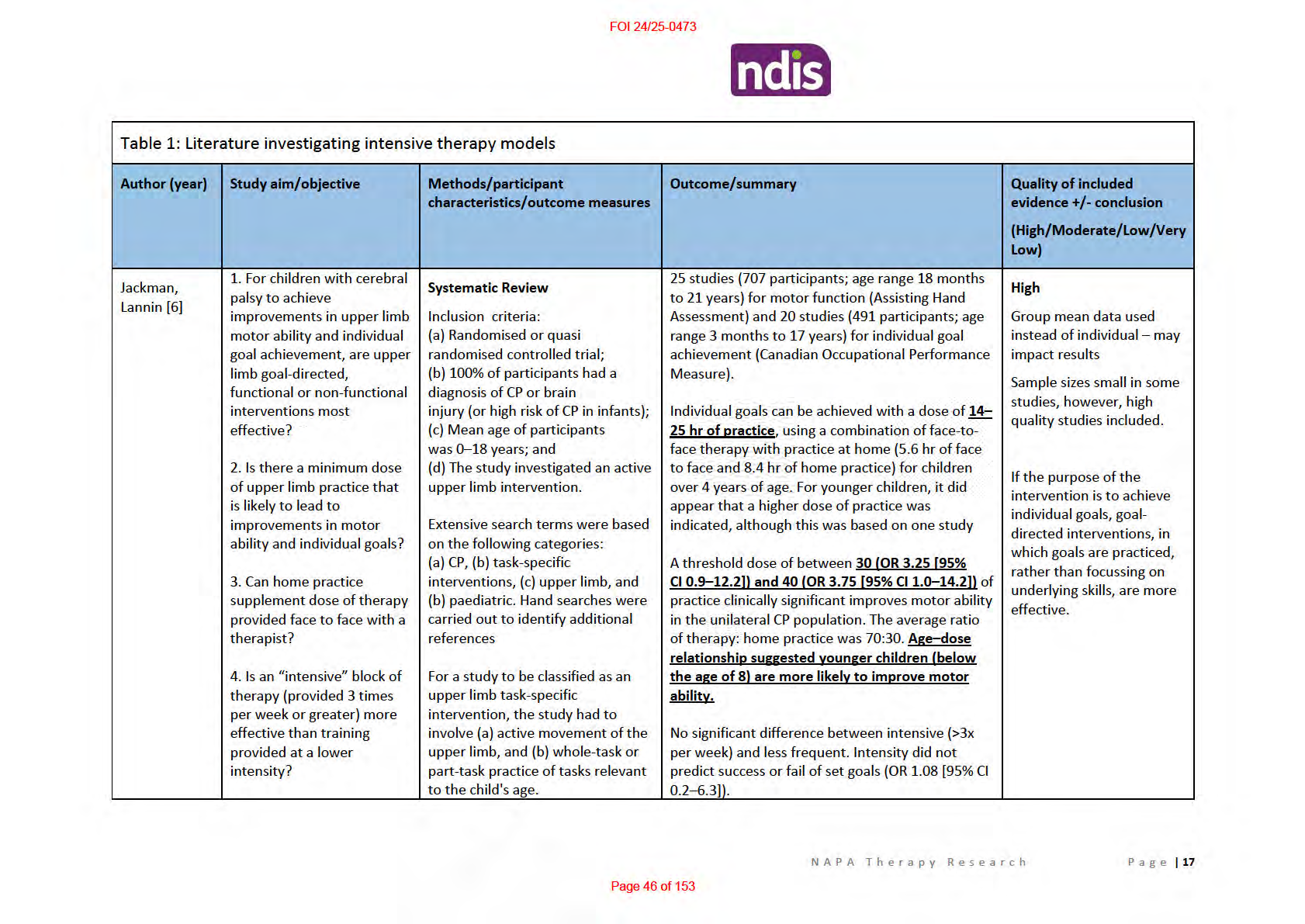

Although it has been hypothesized that the effectiveness of conventional therapy in children with CP

may depend on the dosage of treatment (i.e. with intensive regimens being more effective), this

assumption is far from proven. Various systematic reviews and meta-analyses (moderate to high

quality) have been published that investigate dosages required to obtain improvements [6] and have

compared conventional to intensive therapy [2, 5, 7] (see Table 1 for more in-depth data). The main

outcomes from these reviews are as follows:

In relation to upper extremity therapy [6]

• Individual goals can be achieved with a dose of

14–25 hr of practice, using a combination of

face-to-face therapy with practice at home (5.6 hr of face to face and 8.4 hr of home

practice) for children over 4 years of age

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

4

Page 33 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

• A threshold dose of between

30 (OR 3.25 [95% CI 0.9–12.2]) and

40 hrs (OR 3.75 [95% CI

1.0–14.2]) of practice clinically improves motor ability in the unilateral CP population. The

average ratio of therapy: home practice was 70:30.

o Age–dose relationship suggested younger children

(below the age of 8) are more

likely to improve motor ability.

• No significant difference between intensive (>3x per week) and less frequent. Intensity did

not predict success or fail of set goals (OR 1.08 [95% CI 0.2–6.3]).

*It is reasonable to assume that these figures can be transferred to other goal based functional tasks

of the lower extremities.

Comparison of conventional to intensive treatment which target motor and functional skills

(delivered by occupational therapist, physical therapist and/or physiotherapist) showed mixed

results.

• Myrhaug, Østensjø [2] found that across the majority of studies included in their review,

equal improvements were identified between intensive intervention and conventional

therapy or between two different intensive interventions.

• Alternatively, Cope and Mohn-Johnsen [7] and Arpino, Vescio [5] found smal positive

treatment effects in favour of intensive therapy, however, based on the GMFM-88 manual

the level of difference is

not considered clinical y important/noticeable. [8]

Taking a closer look at some of the high quality randomised controlled trials included in these meta-

analyses it is clear that intensive and standard treatment can both lead to improvements in GMFM.

Given that long term follow-up data is sparsely reported, and conventional treatment of 1-2 sessions

per week still leads to significant improvements in motor and functional skills it is difficult to justify

intensive treatment which is more costly, time consuming and tiring/stressful for children. [5]

In addition, there is research of reasonably low to moderate quality which looks at the potential

benefits of intensive strength training. For example, strengthening programs with frequencies of up

to 3 times a week demonstrate improvements in gait and function. [9-13] Protocols have more

commonly been home/community based [9, 11, 12] and have reported changes in gross motor

function [9, 11, 13] cadence, and walking speed. [9, 12, 13] Although these results are positive (and

strength training is wel recognised as a high quality treatment for CP), many studies did not include

a control group to allow for comparison against lower dosages.

Difference between intensive therapy as described in the literature and NAPA therapy

Whilst there are positive findings in the literature (although rarely clinically important or shown to

be sustained over the long term) relating to various types of intensive therapy, we must consider

how this compares to the method proposed by NAPA.

The NAPA program usually consists of 2-6 hours of treatment a day, 5 days a week over 3 weeks. The

vast majority of the literature investigating intensive interventions consists of 3-5 sessions (45-60

minutes in duration) a week over 5-12 weeks. The only other treatment which promotes a dosage as

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

5

Page 34 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

high as NAPA therapy is Constraint Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT) which has been shown to

range between 1 to 24 hours a day, over a period of two weeks to two months, however, much of

this is parent led/home practice. CIMT is a recommended treatment option as it has an immense

amount of favourable high quality published literature and a good safety profile for those with a

diagnosis of CP.[14, 15] In comparison, NAPA therapy utilises a “core combination” of the Neurosuit,

SpiderCage and Cuevas Medek Exercise (CME). None of which are considered effective (‘do it’ or

‘probably do it’) interventions for CP. [14]

Suit therapy

The original suit (Adeli suit) was developed for the Soviet space program in the late 1960’s and was

referred to as the Penguin suit. It was designed to counteract the adverse effects of zero gravity

including muscle atrophy and osteopenia, and maintain neuromuscular fitness during

weightlessness. [16] In 1991, the Adeli suit incorporated a prototype of a device developed in Russia

for children with CP and popularized by the EuroMed Rehabilitation Center in Mielno, Poland. [17]

Since then, the suit has been popularised in different countries using different names (Therasuit,

Neurosuit, PediaSuit etc.). [16, 18] These different suits are essential y the same thing, however,

they are marketed according to their own ‘protocols’. The differences between these ‘protocols’ are

not clear in the literature, and most interventions use a combination of suits with intensive physical

therapy (i.e. 2-4 hr sessions, 5-6 days a week, over 3 or 4 weeks). [18] Non-peer reviewed literature

from developers of these suits claim that the therapy is appropriate for children from 2 years of age

to adulthood. [18, 19]

In addition to the suit, some protocols use ability exercise units or functional cages. These cages can

be used in two ways: the ‘monkey cage’ uses a system of pul eys and weights to isolate and

strengthen specific muscles; and the ‘spider cage’ (Figure 1) uses a belt and bungee cords to either

assist upright positioning or practice many other activities that normal y would require the support

of more therapists. [18] Claims of “significant improvement” following body weight suspension

training have been made, however, only 3 peer reviewed articles exist. All of which are

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

6

Page 35 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

methodologically weak and include small samples making it impossible to make conclusions about

its effectiveness. [20-22]

Figure 1. Spider cage and universal therapy unit.

Some of the many reported benefits include improving motor function and posture, [23] improving

vertical stability (e.g. standing posture), [24] increasing range of motion, [25] providing

proprioceptive input and improving the vestibular system improving symmetry, [26] increasing

walking speed and cadence, [27] improving trunk, [28] control motor function (in all dimensions of

Gross Motor Function Measure [GMFM]), [29] and self-care [30] capacity in children with CP.

However, most of these studies are case reports or descriptive studies in which the methodological

quality limits the possibility of supporting or rejecting the use of the suit therapy in clinical settings.

Centres that offer suit therapy indicate that the therapy can help children diagnosed with: [31, 32]

• Cerebral Palsy

• Global Developmental Delays

• Traumatic Brain Injury

• Near Drowning Accidents

• Post stroke (CVA)

• Incomplete Spinal Cord Injury

• Ataxia

• Athetosis

• Spasticity

• Hypotonia

• Parkinson Disease

• Chromosomal Disorders

• Autism Spectrum Disorder

There are no published, peer-reviewed studies on any of the above listed diagnoses, except for CP.

Three moderate to high quality systematic reviews were analysed to obtain evidence on the benefit

of participation in intensive suit therapy for children and adolescents with CP. These reviews are

summarised in Table 2 below.

The main take-home messages from the analysis were:

• Evidence indicating greater functional benefit from participation in intensive suit therapy is

limited.

• No studies investigated the feasibility (e.g. adherence/compliance) or cost-effectiveness of

suit therapy

• It is not possible to draw conclusions regarding which children with CP may benefit more

than others from suit therapies due to the limited evidence and heterogeneity of included

participants (GMFCS level I-IV)

• There is no consensus with regard to frequency, intensity and timing due to the variability in

doses delivered across studies. Often specific protocols (including other physical therapy

interventions concurrently delivered) were not described in studies. This makes it extremely

difficult to evaluate findings.

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

7

Page 36 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

• Results from a meta-analysis showed a

smal positive effect size for gross motor function at

post treatment (g=0.46, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.10–0.82) and follow-up (g=0.47, 95%

CI 0.03– 0.90). This small effect

does not support robust conclusions to prescribe or suggest

this new and ‘promising’ approach to therapy.

• Furthermore, adverse effects such as overheating, respiratory compromise, toileting

problems such as constipation and urinary leakage and peripheral cyanosis have been

reported. [16, 33]

Cuevas Medek Exercise

Cuevas Medek Exercise (CME) is a specialised psychomotor therapy designed for infants with

developmental delays, syndromes and conditions affecting the central nervous system. [34] CME

therapy provokes the child's automatic postural responses by exposing the infant to the influence of

gravity through a variety of positions and exercises (approximately 3000 exercises exist). During

CME, the therapist physically manipulates the child to stretch out tight muscles and train the

muscles in groups. These manipulations eventually allow the child to gain control over his or her

trunk, which is necessary to perform basic gross motor activities such as sitting, standing, and

walking. Sessions begin on a table. Then, if the child is able to stand with ankle support, the floor is

used. Floor exercises involve seven pieces of equipment, which can be configured in various ways to

challenge the child’s sense of balance. Exercises are repeated until the reaction of the brain becomes

automatic and the body reacts normal y to situations where required to keep its balance.

It should be noted that CME rejects the use of external supports (splints and walkers) and the

exercises are manually applied by a therapist, rather than the patient having to physical y make the

movements themselves. Below is an excerpt from the thesis titled

The social construction of

disability and the modern-day healer by Vanderminden [35]which describes the process of CME as

described by its creator, Ramon Cuevas.

“CME therapy can be exercised regardless of the emotional status of the child, while in classical

approaches, if the child cries the therapy session is typically terminated. When considering a child's

muscle tone, classic approaches generally wil not place a child with hyper tonicity or severe

spasticity in the standing position. Conversely, CME therapy practices the exact opposite. CME

therapy does not require a physician's diagnosis of a child's condition, but rather seeks to listen to the

parent's interpretation of the limitations of their child's development and movement.” CME is claimed to be suitable for babies from 4 months old, until they are walking and climbing

stairs, however due to the nature of the technique, therapists are only able to work with children of

a certain weight (up to approximately 22.5kg/50 pounds). [34] The therapy is suggested to occur

three times a week, twice a day, for 45 minutes per session. [36]

Studies focused on CME are scarce. Apart from reports published by the creator of the technique,

only two case reports published in very low ranked (Impact Factor <1.5) peer reviewed journals

could be located. [36, 37] These studies report that technique leads to positive results, however,

several factors need to be considered.

1) Treatment protocols were poorly reported

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

8

Page 37 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

2) Unclear what outcome measures were used to determine “positive” results

3) No statistical analysis

4) Small samples/case reports

a. Unclear how participants were selected and allocated to groups in the report with

multiple participants [37]

Given the lack of scientific evidence or identification of possible adverse effects of this treatment it

cannot be considered an evidence based practice. It should also be noted that CME is not listed as an

intervention for CP in the high quality systematic review by Novak, Morgan [14] or the American OT

association review into interventions to improve motor performance [38], furthermore, other

authors have cal ed for the treatment to be “discontinued based on current evidence.” [39]

Home based programs

Home programs have been used for years by families and therapists to increase the intensity of

therapy, either between treatment sessions or during a break from therapy. Recent research into

therapy intensity has concluded that home programs provide a pragmatic solution to achieving high

dose therapy, thus overcoming existing systemic implementation barriers.[2, 40]

In relation to upper limb mobility, there is little evidence to support block therapy alone as the dose

of intervention is unlikely to be sufficient to lead to sustained changes in outcomes. [40] There is

strong evidence that goal-directed OT home programs are effective and could supplement hands-on

direct therapy to achieve increased dose of intervention. [41] Embedding intervention in natural

environments (e.g., home, preschool/school) has been suggested to lead to meaningful and

generalizable improvements in function. [42]

Clinically proven high dose interventions such as bimanual training and constraint-induced

movement therapy (CIMT) have been shown to be effective when delivered at home. [43-45] Home

based interventions are beneficial, especially for interventions with dosages that are not feasible for

most families.

Novak, Cusick [42] have developed five steps for delivering successful home based programs. This

includes:

1) Establishing collaborative partnerships between therapist and caregivers

2) Having the child and family (not the therapist) set goals about what they would like to work

on in the home environment

3) Establishing the home program by choosing evidence based interventions that match the

child and family goals and empowering the parents to devise or exchange the activities to

match the child’s preferences and the unique family routine

4) Providing regular support and coaching to the family to identify the child’s improvements

and adjust the complexity of the program as needed; and

5) Evaluating the outcomes together

Based on the steps, therapy provided by NAPA would not be successful in a home based

environment because:

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

9

Page 38 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

a) The core interventions (suit therapy, spider cage and CME) are not evidence based

b) They cannot be performed in the home without the equipment utilised in the clinic

c) The NAPA centre is not local for many patients so provision of support and development of a

collaborative partnership will be near impossible without regular interaction between

therapists and patients/families

d) Outcomes won’t be able to be evaluated unless further blocks of NAPA therapy are provided

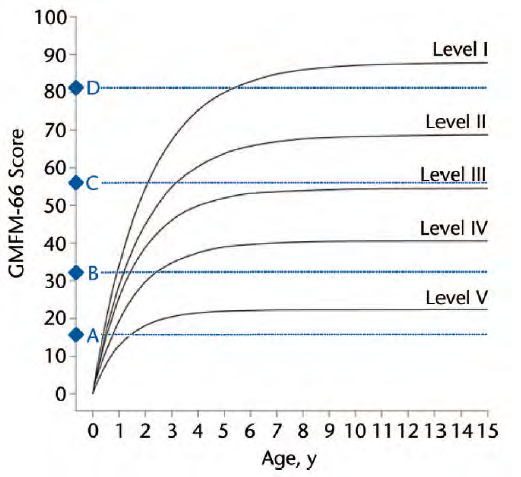

Neuroplasticity and Gross Motor Function Classification Scores

Neuroplasticity is the brain’s adaptive capacity to encode experiences as well as learn new

behaviours and skills. In children with CP, intervention before the age of seven is recommended for

optimizing motor function and learning functional skills, because from a maturational and

neuroplasticity perspective the greatest gains wil be made during this window. [46-48]

A younger child with a GMFCS level I or II usually has a better developmental prognosis than an older

child with a GMFCS level IV or V. [49]

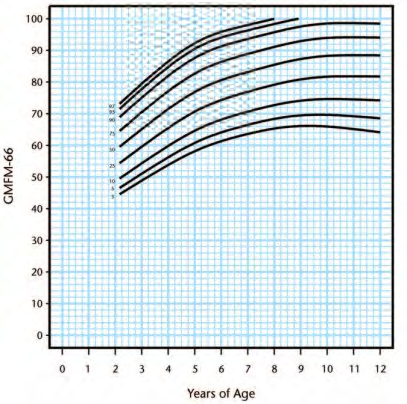

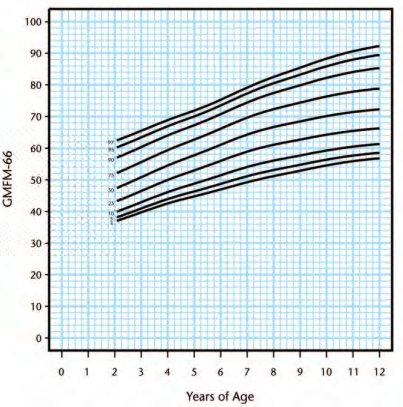

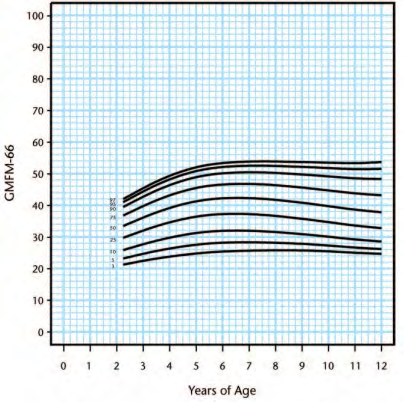

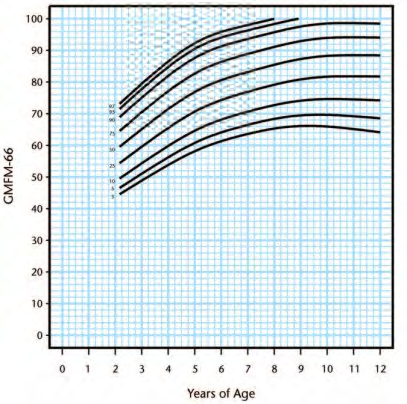

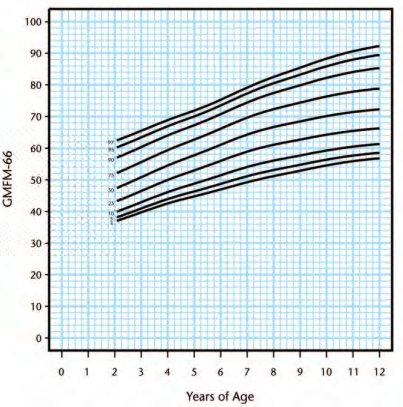

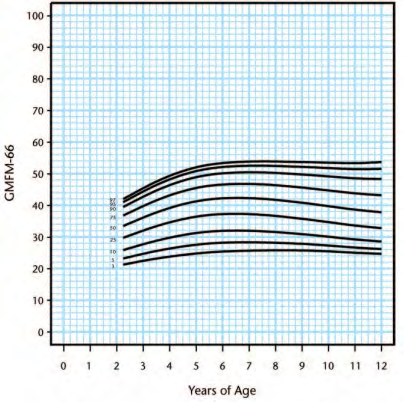

Gross motor development curves based on age and GMFCS level have been created by Rosenbaum,

Walter [46] to enable prognosis of gross motor progress (Figure 2). Following this, Hanna, Bartlett

[50] created reference curves which plotted percentiles at the 3rd, 5th, 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th,

95th, and 97th percentiles within each GMFCS level (Figure 3-7). This can be used to determine

percentage potential based using GMFCS scores.

Figure 2. Gross motor development curves representing average development predicted by the Gross Motor

Classification System. The diamonds on the vertical axis identify 4 items of the 66-item Gross Motor Function

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

10

Page 39 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

Measure (GMFM-66) that predict when children are expected to have a 50% chance of completing that item

successful y. The GMFM-66 item 21 (diamond A) assesses whether a child can lift and maintain his or her head

in a vertical position with trunk support by a therapist while sitting, item 24 (diamond B) assesses whether a

child can maintain a sitting position on a mat without support from his or her arms for 3 seconds, item 69

(diamond C) measures a child’s ability to walk forward 10 steps without support, and item 87 (diamond D)

assesses the task of walking down 4 steps by alternating feet with arms free.

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

11

Page 40 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

Figure 3. Gross Motor Function Classification System level I percentiles.

Figure 4. Gross Motor Function Classification System level II percentiles

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

12

Page 41 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

Figure 5. Gross Motor Function Classification System level III percentiles

Figure 6. Gross Motor Function Classification System level IV percentiles

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

13

Page 42 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

Figure 7. Gross Motor Function Classification System level V percentiles

Progressive disorders

Childhood neurodegenerative and neuromuscular disorders are rare, and usual y have no cure. The

natural history is often unknown and progression varies across patients.

Congenital neuromuscular disorders

Congenital neuromuscular disorders include:

• Muscular dystrophy

• Myotonic dystrophy

• Spinal muscular atrophy

• Peripheral neuropathies

• Generalised muscle and nerve issues (such as mitochondrial disorders)

The management of paediatric neuromuscular disorders is complex and challenging. Developing an

effective management plan requires an understanding of the underlying pathophysiology, genetics,

and natural history, as well as the interactions of normal maturation, treatment modalities, and the

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

14

Page 43 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

environment. [51, 52] Optimum management requires a multidisciplinary approach that focuses on

preventive measures as well as active interventions to address the primary and secondary aspects of

the disorder. [51]

Physical therapy interventions

Active, active-assisted, and/or passive stretching to prevent or minimise contractures should be

done a minimum of 4–6 days per week for any specific joint or muscle group. Stretching should be

done at home and/ or school, as well as in the clinic. [51]

Nowhere in the literature is there mention

of providing short-term intensive therapy (physio, OT or speech) blocks as part of the

management plan for neuromuscular disorders. Figure X below provides a comprehensive overview of neuromuscular and skeletal management

strategies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. [51]

Figure X. neuromuscular and skeletal management strategies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy

Neurodegenerative Disorders in Childhood

Normal neural development and behaviour is relatively wel understood, much less is known about

the behavioural neurology of neurodegenerative deterioration in children. [53] It is unknown how

the developing brain is impacted by progressive diseases at both a global and selective level. [53, 54]

Frequently, the assessment of the severity of symptoms in children with neurodegenerative

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

15

Page 44 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

disorders (NDD) is difficult. Age and understanding of the child are always a factor and, in addition,

many children suffer from brain damage or intellectual disability as a result of their disease. [53]

Treatment of children with NDD is directed towards the underlying disorder, other associated

features, and complications. [55] The treatable complications include; epilepsy, sleep disorder,

behavioural symptoms, feeding difficulties, gastroesophageal reflux, spasticity, drooling, skeletal

deformities, and recurrent chest infections. [55] These children require a multidisciplinary team

approach with the involvement of several specialties including paediatrics, neurology, genetics,

orthopaedics, physiotherapy, and occupational therapy. [55] Many newer antiepileptic drugs are

now available to treat intractable epilepsy. [54]

owhere in the literature is there mention of

providing short-term intensive therapy (physio, OT or speech) blocks as part of the management

plan for NDD. An investigation by Olney, Doernberg [56] identifed 104 progressive brain disorders of childhood

which may be mistaken for CP. The natural history of many of these conditions is unknown as

insuffient numbers of cases are reported in the literature. [56]

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

16

Page 45 of 153

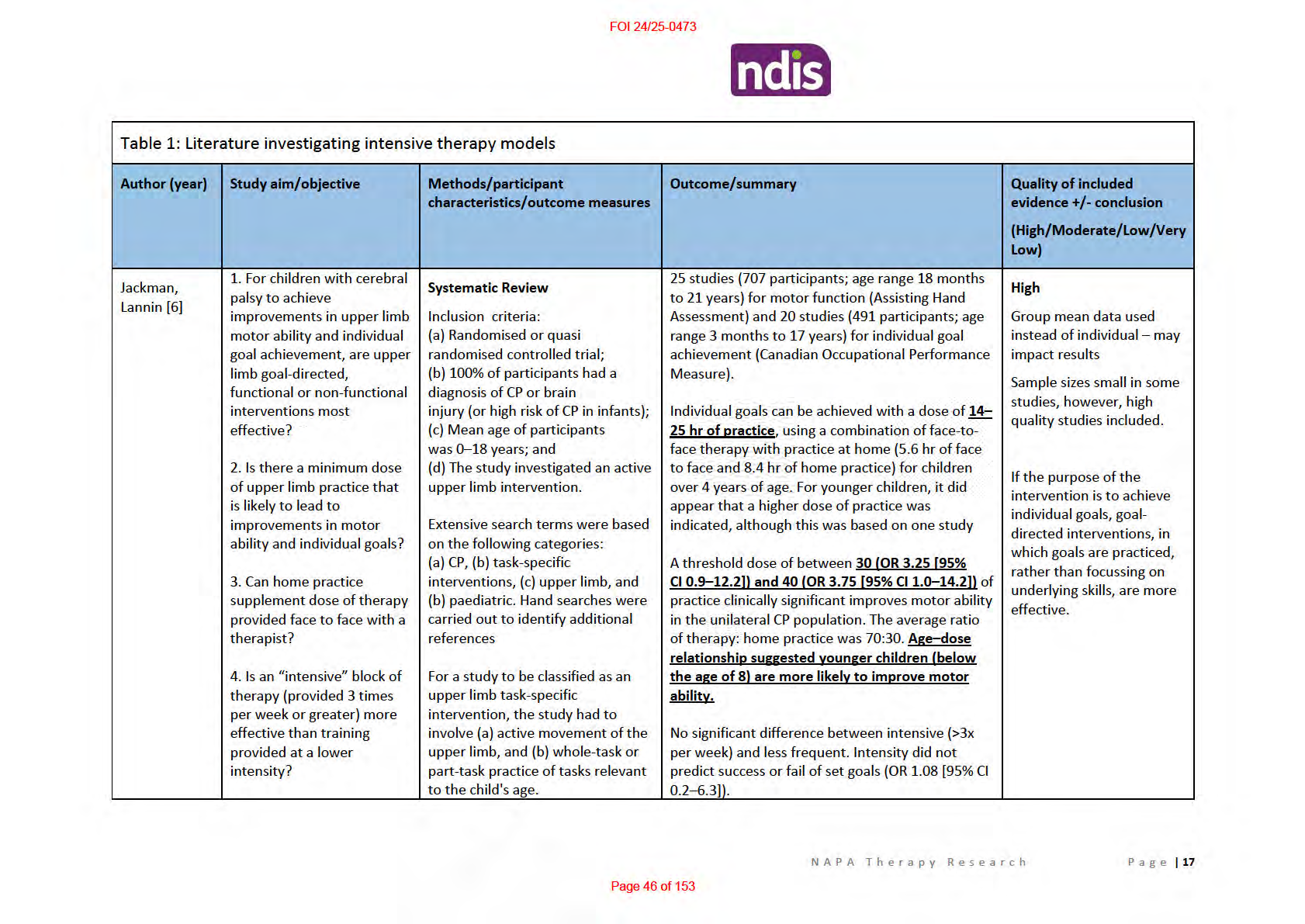

FOI 24/25-0473

5. Is there an age–dose

relationship?

Outcome measures

Practice at home appears to be an effective

AHA, Quality of Upper Extremity

enhancement to face-to-face therapy. It is likely

Skil s Test (QUEST), Melbourne

that if families are educated and supported to

Assessment 2, The Box and Blocks

carry out practice at home, that this practice can

Test, Abilhand-Kids, COPM, The

be an effective and cost-effective enhancement in

Goal Attainment Scale (GAS), the

achieving goals. Practice within everyday

Pediatric Evaluation of Disability

environments may also facilitate transfer of skil s

Inventory (PEDI), and the

beyond the clinic to the child's real life.

Functional Independence Measure

for children (WeeFIM). The AHA

and COPM were the most

commonly utilised reliable

outcome measures within eligible

studies

Cope and

(1) In children with cerebral

Systematic Review & Meta-

9 RCTs and 1 retrospective non-randomized

Moderate

Mohn-

palsy, is therapy provided

Analysis

control ed trial (388 participants, age 4 months to

Johnsen [7]

for a greater total number

16 years)

Methods of review were

of minutes more effective

inclusion criteria: Study design

robust. Included studies

than the same intervention

must include the same treatment

The functional level of the participants ranged

highly variable.

provided at fewer total

across at least one of three

from I to V on the GMFCS. The majority of

minutes for improving

dosage variables, specifical y: (a)

participants throughout the studies included

motor function? (Time)

compare treatment time, defined

children with spastic cerebral palsy.

Not enough evidence exists

for this review as any contrast

to determine if higher

(2) In children with cerebral in the total number of minutes; (b) The majority (8 of 10) of studies utilized either an

frequency therapy is more

palsy, is therapy provided at compare treatment frequency,

eclectic (treatment not limited to one specific

effective than lower

higher frequency

defined for this study as any

intervention) or neurodevelopmental treatment

frequency.

(intermittent) more

contrast in scheduling of frequency (NDT) approach

effective than the same

(intermittent versus continuous)

intervention provided at a

where total minutes of therapy

The high-dosage therapy conditions ranged in

The findings from this

lower frequency

remain constant; and (c) compare

frequency from one to seven times per week, with review are limited to short-

(continuous) for improving

intensity in which the amount of

total therapy hours over the treatment duration

term effects only; fol ow-

motor function?

effort by the study participant is

ranging from 9 to 126 hours. Low-dosage therapy

up data were sparsely

(Frequency)

varied by group;

conditions ranged in frequency from one time per

reported.

month to seven times per week, with total therapy

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

18

Page 47 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

(3) In children with cerebral intervention must be provided by a hours over the treatment duration ranging from 6

palsy, is intervention

PT or OT intervention may focus on to 78 hours.

performed at a higher

upper and/or lower limb; outcomes

intensity more effective

measures include impairments of

Results showed a

smal treatment effect favouring

than the same intervention

body structure/ function, activity

the higher dosage time (pooled g = 0.277, 95% CI

performed at a lower

limitations, and/or participation

0.02, 0.534; I2 = 0%), however, this benefit is

not

intensity for improving

restrictions; participants must be

clinically important.

motor function? (Intensity)

children, birth to 18 years with a

diagnosis of cerebral palsy;

Al individual between group differences showed

publication in peer-reviewed

wide confidence intervals that crossed zero,

journals in any language with

suggesting both lack of precision in the computed

English version available;

effect sizes and the possibility that there was no

control ed trials with two or more

difference between the groups.

groups.

Data extracted

study design, sample size, subject

demographics, intervention

parameters, outcome measures,

fol ow up procedures, baseline and

post treatment group means and

measures of variability, within-

group change scores and measures

of variability, and statistical

significance for within group and

between-group comparisons

Myrhaug,

To describe and categorise

Systematic review & Meta-

38 studies included 1407 children with al levels of

Moderate

Østensjø [2]

intensive motor function

gross and fine motor function

and functional skil s training

Analysis

Smal studies, often

among young children with

Inclusion criteria: (a) a study

Only 6/38 studies performed intervention more

without power

CP, and to summarise the

population of CP with a mean age

than 1 hr a day. More common for 2-7 sessions a

calculations, were also

effects of these

<7 years; (b) evaluated the effects

week + home training (19/38) and these were

included. A variety of

interventions.

of motor function (e.g., mobility

mainly hand function interventions.

interventions were used to

and grasping) and functional skil s

improve gross motor

training (e.g., eating and playing)

In a majority of the studies, equal improvements in function and functional

performed three times or more per motor function and functional skil s were identified skil s, which prevented the

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

19

Page 48 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

week at the clinic, in the

for intensive interventions and conventional

pooling of results in the

kindergarten, or at home; (c) was

therapy or between two different intensive

meta-analyses.

compared to another intervention

interventions

19/38 studies had high risk

(e.g., conventional therapy), the

of bias. Therefore, results

same type of intervention provided

Hand function (fine motor skills)

remain uncertain.

less frequently, or another

When compared with conventional therapy, CIMT

intensive intervention; and (d) with performed for more than one hour per day showed The identification of the

outcomes in the activity and

significant effects on unilateral hand function in

optimal intensity of

participation components of the

one meta-analysis (N = 2, [33,60] SMD 0.79 (95% CI interventions that target

ICF [3], measured as hand function, 0.03, 1.55), p = 0.04). The CIMT groups performed

motor function and

gross motor function, and/or

15–28 hours more training per week, which

functional skil s, as wel as

functional skil s.

resulted in a difference of 29–84 training hours

the possible harmful

over two to three weeks compared with the

effects of intensive

In addition, the included studies

conventional therapy groups.

training, requires further

were required to be control ed

investigation.

trials, published in peer review

Gross motor function

journals

Too heterogeneous to be pooled in meta-analyses.

All studies with significant results in favour of

Data extracted

intensive training that targeted gross motor

study population, design,

function had a high risk of bias.

interventions, comparison,

outcome measures, and results

Functional skills

CIMT performed at least 2–7 sessions per week

The intensity of training was

with additional home training achieved more

described as the amount of training improvements in functional skil s compared with

and duration of the training

conventional therapy (N = 3, [36,38,60] SMD 0.82

periods. The amount was

(95% CI 0.26, 1.38), p = 0.004) and (2) CIMT

categorised into four groups

performed 2–7 sessions per week with additional

according to frequency of sessions

home training achieved more improvements

and use of home training: (1) 2–7

in functional skil s compared with intensive

training sessions per week with

bimanual home training (N = 4, [21,30,32,34] SMD

additional home training, (2) 3–7

0.50 (95% CI 0.16, 0.83), p = 0.004)

training sessions per week, (3)

training more than one hour per

day, and (4) training more than one

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

20

Page 49 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

hour per day with additional home

training.

The duration was categorised as ≤

four weeks, 5–12 weeks, or >12

weeks.

Arpino, Vescio To assess whether intensive

Systematic review & Meta-

Meta-analysis showed that the GMFM change

High

[5]

‘conventional therapy’ is

score was higher for the intensive treatment

more effective than non-

analysis

group, compared with the non-intensive treatment

According to the

intensive ‘conventional

Type of study: RCT

group

[difference of 1.32; 95% confidence interval GMFM-88 manual an

therapy’ in children with CP

(CI): 0.55–2.10].

increase of 1.82% points is

whose clinical outcome was Type of participants:

the smal est change of

assessed with the GMFM.

infant/children/adolescents (1–18

Effect of intensive treatment tended to be stronger

clinical importance

years old) affected by any type of

for children who were 2 years of age or younger

according to parents’

CP.

(difference of 5; 95% CI: – 0.45–10.45).

perception

Outcome measure: GMFM.

In the RCTs in which treatment lasted for at least

Limited evidence to

‘intensive’ treatment was defined

60 days, it was higher in the intensive treatment

support

as any treatment provided more

group than in the non-intensive treatment group

intensive/additional

than 3 times per week; in a single

(difference of

1.42; 95% CI: 0.55–2.30).

physiotherapy

study, additional sessions provided

by an assistant defined the

‘intensity’ of the treatment.

‘Conventional therapy’ that which

included physiotherapy or a

neurodevelopmental approach.

Elgawish and

To assess gross motor

Randomised control ed trial

After 8 weeks, there were significant differences

Moderate

Zakaria [41]

progress in children with

between the two groups as regards the total

spastic (quadriplegic and

Patients were randomly assigned

scores of GMFM-88 and GMPM (

P < 0.05).

Convenience sample.

diplegic) CP treated with

to two treatment groups: group A

Randomisation not

intensive physical therapy

and group B

However, highly significant differences for

specified, no power

(PT) as compared with a

GMFM-88 (

P < 0.001) and only significant

calculation.

matched group treated with Convenience sample.

differences (

P < 0.05) for GMPM were observed

a standard PT regimen.

after 16 weeks.

Intensive PT = 5 sessions (1hr each)

Intensive PT led to greater

a week, over 16 weeks

motor function

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

21

Page 50 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

Standard PT =2 sessions (1hr each), No statistical y significant differences were found

improvements. However,

over 16 weeks

between the two groups as regards GMFM-66

even 1hr, twice a week

scores after 8 weeks, and significant differences

leads to significant

25 girls and 20 boys, aged between were found only after 16 weeks (

P < 0.05).

improvements.

2 and 6

Years

After 16 weeks, al dimensions of GMFM-88 were

significantly increased in both groups (P < 0.001).

GMFCS level I - V

Christiansen

to compare the effect of the

Randomised control ed trial

Both groups increased their GMFM scores

Moderate

and Lange

delivery of the same

significantly over the study period (I group

[57]

amount of intermittent

25 children up to 10 years of age

p=0.026; C group p=0.038).

Convenience sample.

versus continuous

(16 males, nine females; median

Randomisation not

physiotherapy given to

age 3y 2mo, range 1y 2mo–8y

Result does not confirm the hypothesis that

specified. More studies

children with cerebral palsy 9mo)

intermittent physiotherapy increases the GMFM-

required.

(

Convenience sample.

66 score more than continuous physiotherapy

GMFCS level I – V

Intermittent = physiotherapy 4x a

week, 45 minutes per session for 4

weeks (period A) fol owed by 6

weeks without physiotherapy

(period B). Periods A and B were

repeated three times over 30

weeks with a maximum of 48

sessions

Continuous = physiotherapy once

or twice a week for 30 weeks, also

for 45 minutes per session and with

a maximum of 48 sessions

Children were treated by ‘their

own’ physiotherapist during the

intervention

Outcome measure

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

22

Page 51 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

GMFM-66

Bower,

to determine whether

Randomised control ed trial

There was no statistical y significant difference in

Moderate

Michel [58]

motor function and

the scores achieved between intensive and routine

performance is better

A convenience sample of 56

amounts of therapy or between aim-directed and

Randomised, power

enhanced by intensive

children with bilateral CP classified goal-directed therapy in either function or

calculation and good CI

physiotherapy or

at level II or below on the Gross

performance.

estimates.

collaborative goal-setting in Motor Function Classification

children with cerebral palsy System (GMFCS), aged between 3

Intensive physiotherapy, in contrast to

The results of this trial

and 12 years.

collaborative goal-setting, produced a trend

suggest that for children

aged 3 to 12 years with

4 treatment regimens provided by

towards improvement in the GMFM scores which

bilateral CP at levels II or

their own physiotherapist during

was not statistical y significant. This trend declined below on the GMFCS,

the treatment period: (1) current

in the fol ow-up observation period.

altering their routine

pattern of physiotherapy to

physiotherapy by

continue for each child; (2) current

increasing its intensity for a

pattern of physiotherapy to be

period of six months has

provided more intensively, one

very little effect upon the

hour per day Monday to Friday; (3)

outcome of gross motor

therapy to be guided by

function or performance at

col aborative setting of specific,

the end of this time.

individual, and measurable goals at

the current intensity, i.e. amount

as in Group 1; (4) therapy to be

guided by col aborative setting of

specific, individual, and measurable

goals and provided more

intensively, one hour per day

Monday to Friday

Outcome measure

GMFM-88

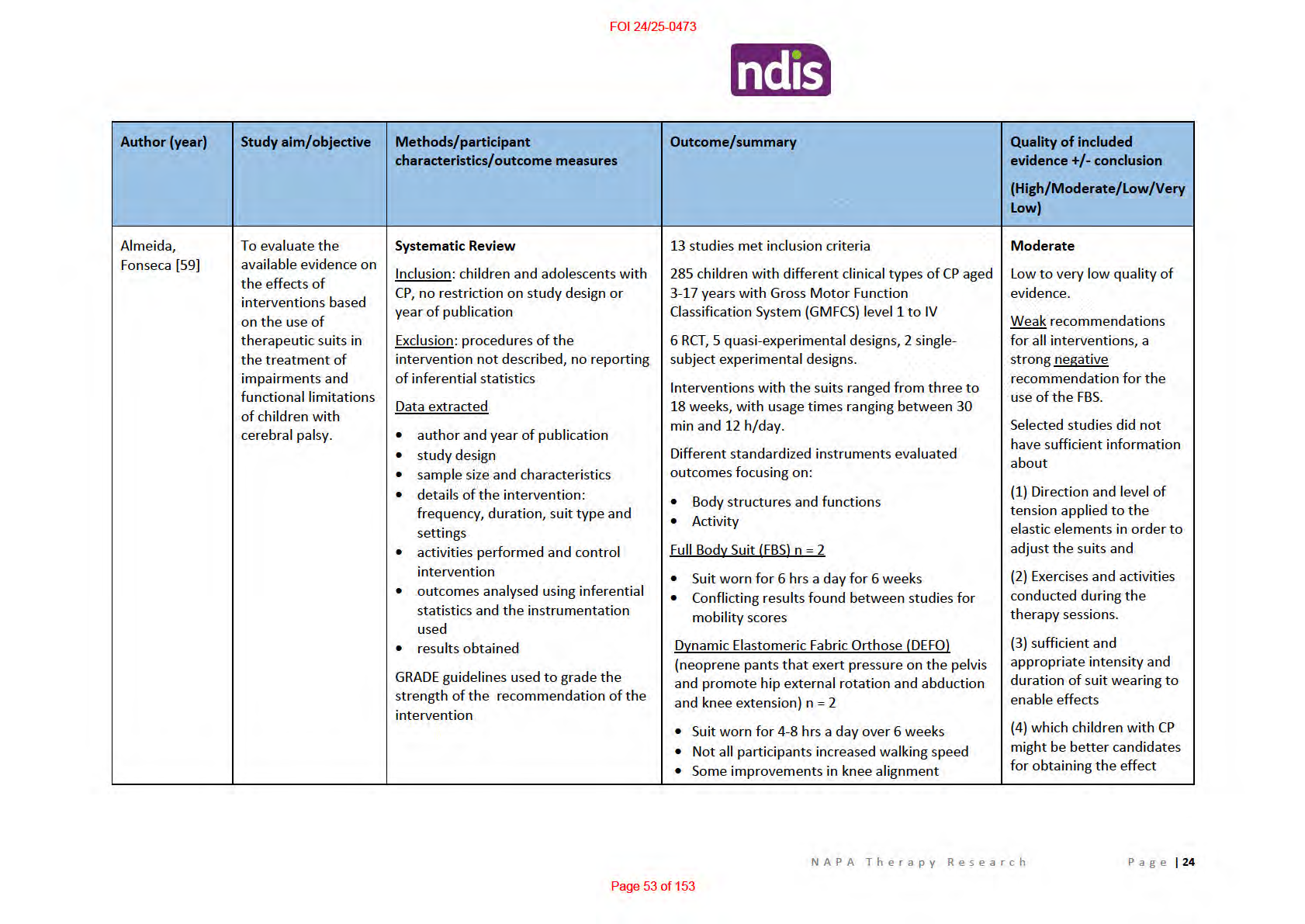

Table 2. Summary of systematic reviews investigating intensive suit therapy as a treatment for CP

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

23

Page 52 of 153

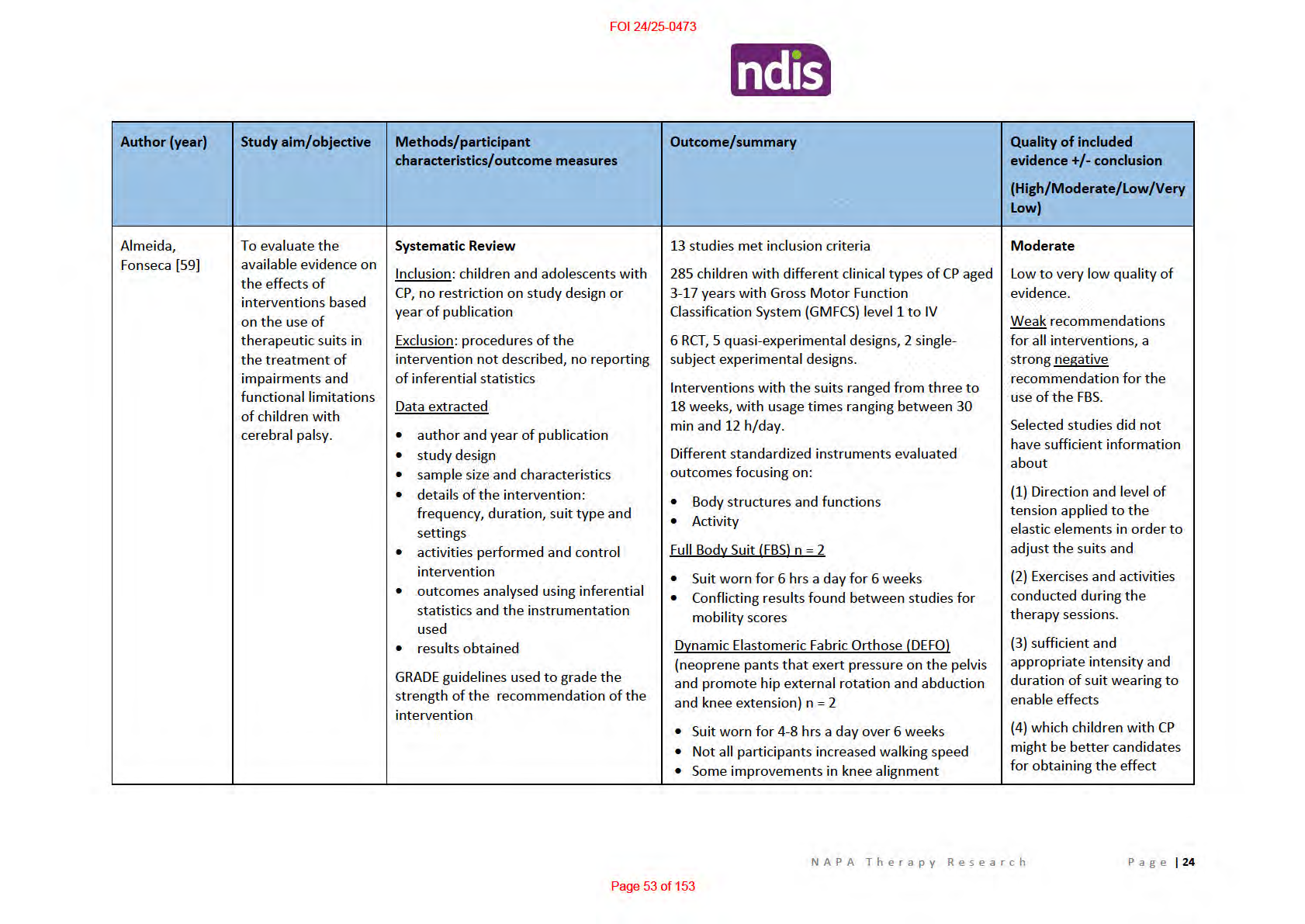

FOI 24/25-0473

• Wearing this suit did not lead to significant

difference in postural control

TheraTogs n = 3

• Suit worn 12 hrs a day for 12 weeks

• Significant improvement seen in gait kinematics

across all studies compared to control groups

TheraSuit Method (TSM) or AdeliSuit Therapy (AST)

n = 6

• Both Therasuit studies found minimal gain

(smal positive effect sizes).

• No statistical y significant differences between

groups [23, 27]

• Some areas there was a decline in gross motor

function [27]

• Those with higher level motor function at

baseline performed better [23]

• Only care giver perception regarding the

performance of tasks obtained a large effect

size

• Same findings relating to Adeli suit therapy

Karadağ-Saygı

To evaluate the

Systematic Review

29 studies were included of which

Moderate

and Giray [33]

clinical aspects and

10 (34.5%) were Class I, eight were

effectiveness of suit

Inclusion

(27.6%) Class II-I I, and 11 (37.9%) were Class IV

Heterogeneity of studies

therapy for patients

makes it difficult to provide

with cerebral palsy

• Patients: Children (<18 years) with a

diagnosis of CP

Types of participants

any guidance for clinical

•

practice.

• Intervention: Suit therapies

Age ranged between 3 and 14 years.

•

• Comparison: Conventional therapy,

Sample size ranged from 16 to 51.

Smal sample sizes of

neurodevelopmental therapy, or

• Fourteen (48.28%) of the studies did not report included studies and

another therapeutic approach

the GMFCS level of the participants.

varying protocols

Intervention protocols

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

25

Page 54 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

• Outcome: The clinical aspects of

• Intervention protocols varied within and

Included low quality

studies (number of participants, age,

between studies

studies (case studies etc)

CP type, Gross Motor Function

• Suit designs also differed among studies and

Classification System (GMFCS) level,

varied among study participants in some of the

suit type, intervention including dose

studies

Further studies including

of suit therapy, outcome

• Nine (31.03%) of the studies investigated the

large numbers of

measurements, outcomes, adverse

effect of suit on upper limb function, while 10

children with CP at

effects, and funding)

of them investigated effects on lower limb

different functional levels

• Study: All types of trials published in

function (e.g. gait analysis parameters, balance and ages are required in

peer reviewed journals including

or walking performance tests)

order to establish impact

RCTs and non-RCTs and other studies

in children with CP at

(single case studies or case series)

Types of outcome measures

different functional levels

and ages via subgroup

Data extracted

• The Gross Motor Function Measure was the

most reported outcome

analysis

• Number of participants

• Participation evaluated using the International

• Age

Classification of Functioning, Disability, and

• CP type,

Health were limited

• GMFCS level

• Seventeen (58.62%) of the studies did not

• Suit type

report parental satisfaction or adverse effects.

• Intervention including dose of suit

therapy

Results synthesis

• Outcome measurements

• A single RCT of high quality showed that ful

• Adverse effects

body suit therapy in additional to conventional

therapy is beneficial in improving gross motor

function in diplegic CP

• Moderate quality evidence from 4 RCTs

showed that suit therapy in addition to

conventional therapy yields no significant

change in GMFM compared to conventional

therapy in children with diplegic and tetraplegic

CP.

• None of the studies investigated the feasibility

(e.g adherence/compliance), and cost-

effectiveness.

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

26

Page 55 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

• Adverse effects were reported in 11 of the

included studies. The reported undesirable

effects were difficulty in donning/doffing,

toileting problems such as constipation and

urinary leakage, decrease in respiratory

function, heat and skin discomfort (e.g.

hyperthermia in summer, cyanosis)

Martins,

An overview of the

Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis

Four studies were eligible and included in the

High

Cordovil [16]

efficacy of suit

review

therapy on

Inclusion criteria

Overal , studies were rated

functioning in

110 participants included

as ‘fair’ to ‘good’ quality

children and

• RCTs reported in peer-review

using the PEDRO scale.

adolescents with

journals

Mean number of participants in each trial was 12.3

cerebral palsy.

• Languages: English, Portuguese,

(SD 2.52) with a mean age of 6 years 11 months

The results of the study

Spanish and French

(SD 1y 10mo).

point to limited effects of

• Studies investigating the effect of

suit therapy in gross motor

suit therapy regardless of the type of

function of children and

• Two RCTs compared Adeli suit treatment with

protocol used (Pedia- Suit, TheraSuit,

adolescents with CP, and

neurodevelopmental treatment (NDT)

NeuroSuit, Adeli suit, Penguin suit, or

considerable levels of

•

Bungy suit);

one study compared modified suit therapy with heterogeneity between

conventional therapy

• Studies conducted with samples that

trials.

comprised children and adolescents

• One compared TheraSuit with a treatment

(from 0–18y) with a clinical diagnosis

categorized as ‘other’

The presence of potential

of CP regardless of the type and level

co-interventions (such as

of severity

Sample

additional interventions

•

• Studies reporting functioning as the

CP severity ranged from I to IV

and home training of

primary outcome, assessed by means • Subtypes included spastic, ataxic and dyskinetic parents with their children)

of standardized and international y

• Topographic distribution of motor signs –

remained unclear in most

accepted instruments (e.g. GMFM –

hemiplegia, diplegia and quadriplegia

studies and might have

66 or 88 items and Paediatric

• Total hours of treatment ranged from 30-60

influenced outcomes.

Evaluation of Disability Inventory

[PEDI]).

There is no consensus

Data extracted

Adeli suit showed significant improvements in

about the adequate

• Type of study design

gross motor function after 1 month of treatment

duration of suit therapy

• Sample size

(p=0.037). However, there was a decrease in gross programs.

motor function at fol ow up (9 months) and not

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

27

Page 56 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

• Instruments

difference between Adeli suit and NDT when the

• Intervention protocol

retention of motor skil s was tested. This suggests

Health professionals should

• Outcomes

that AST could result in short-term gains quickly,

take into consideration the

although long-term improvements in gross motor

lack of scientific evidence

Methodological quality

function may occur best with traditional NDT

regarding the effectiveness

PEDro scale

methods.

of suit therapy when

advising parents who are

Remaining RCT’s showed variable results:

enquiring about this costly

• 2 showed significant differences between suit

and time-consuming

therapy and conventional/control groups

treatment option.

• 1 showed no difference between TheraSuit and

control suit when delivered as part of an

In summary, the results of

intensive therapy program

this systematic review and

meta-analysis do not

No studies fully specify the type of activities and

support robust conclusions

exercises performed by participants in the

to prescribe or suggest this

experimental conditions who enrol ed in different

new and ‘promising’

protocols of suit therapy, and those in the control

approach to therapy.

conditions.

Meta-Analysis

Small, pooled effect sizes were found for gross

motor function at post treatment (g=0.46, 95%

confidence interval [CI] 0.10–0.82) and fol ow-up

(

g=0.47, 95% CI 0.03– 0.90).

Wells, Marquez To conduct a

Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis

14 studies included in the review (n = 234)

Moderate

[1]

systematic review

asking, does garment Electronic searches of EMBASE,

Age 15 months to 17 years (mean = 8.1 years).

Limited number and

therapy improve

MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, PubMed,

Primary reported impairment was spasticity

varying quality of studies

motor function in

CINAHL and Proquest

(74.76%).

children with

Whilst there is some

cerebral palsy?

Inclusion criteria: Children <18 years,

evidence for the use of

any sub classification of CP, intervention 5 RCT, 9 were case studies (single case study,

garment therapy it is not

involved suit/garment therapy and

repeated measures or case report).

sufficiently robust to

included a measure of neuromuscular

recommend the

function

4 studies full body suits, 6 studies full body suits in

conjunction with a strapping system, 2 upper limb

prescription of garment

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

28

Page 57 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

garment, 1 study lower limb garment, 1 full body

therapy instead of, or as an

suit including gloves. Garment brands were Second adjunct to conventional

Skin, the Adeli Suit, TheraTogs, TheraSuit, UpSuit,

therapy options.

and Camp Lycra

9 described adverse events that may have been a

consequence of the intervention

Intervention duration = 3-12 weeks

Garment wear time = 2-12 hours per day

Meta-Analysis

Non-significant effect on post-intervention

function as measured by the Gross Motor Function

Measure when compared to controls (MD = −1.9;

95% CI = −6.84, 3.05).

Non-significant improvements in function were

seen long-term (MD = −3.13; 95% CI = −7.57, 1.31).

Garment therapy showed a significant

improvement in proximal kinematics (MD = −5.02;

95% CI = −7.28, −2.76), however significant

improvements were not demonstrated in distal

kinematics (MD = −0.79; 95% CI = −3.08, 1.49).

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

29

Page 58 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

8.

Russel DJ, Rosenbaum P, Wright M, Avery LM. Gross Motor Function Measure (GMFM-66 &

GMFM-88) users manual. United Kingdom: Mac Keith Press; 2002.

9.

Damiano DL, Abel MF. Functional outcomes of strength training in spastic cerebral palsy.

Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation [Internet]. 1998 1998/02/01/; 79(2):[119-25 pp.].

Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003999398902878.

10.

Damiano DL, Vaughan CL, Abel ME. Muscle Response to Heavy Resistance Exercise in

Children with Spastic Cerebral Palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology [Internet]. 1995;

37(8):[731-9 pp.]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1469-

8749.1995.tb15019.x.

11.

Dodd KJ, Taylor NF, Graham HK. A randomized clinical trial of strength training in young

people with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology [Internet]. 2003;

45(10):[652-7 pp.]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1469-

8749.2003.tb00866.x.

12.

Eagleton M, Iams A, McDowell J, Morrison R, Evans CL. The Effects of Strength Training on

Gait in Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy. Pediatric Physical Therapy [Internet]. 2004; 16(1). Available

from:

https://journals.lww.com/pedpt/Ful text/2004/01610/The Effects of Strength Training on Gait i

n.5.aspx.

13.

Engsberg JR, Ross SA, Col ins DR. Increasing Ankle Strength to Improve Gait and Function in

Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Pilot Study. Pediatric Physical Therapy [Internet]. 2006; 18(4):[266-75

pp.]. Available from:

https://journals.lww.com/pedpt/Ful text/2006/01840/Increasing Ankle Strength to Improve Gait

and.6.aspx.

14.

Novak I, Morgan C, Fahey M, Finch-Edmondson M, Galea C, Hines A, et al. State of the

Evidence Traffic Lights 2019: Systematic Review of Interventions for Preventing and Treating

Children with Cerebral Palsy. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports [Internet]. 2020

2020/02/21; 20(2):[3 p.]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-020-1022-z.

15.

Hoare BJ, Wallen MA, Thorley MN, Jackman ML, Carey LM, Imms C. Constraint-induced

movement therapy in children with unilateral cerebral palsy. Cochrane Database of Systematic

Reviews [Internet]. 2019; (4). Available from: https://doi.org//10.1002/14651858.CD004149.pub3.

16.

Martins E, Cordovil R, Oliveira R, Letras S, Lourenço S, Pereira I, et al. Efficacy of suit therapy

on functioning in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: a systematic review and meta-

analysis. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology [Internet]. 2016; 58(4):[348-60 pp.]. Available

from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/dmcn.12988.

17.

Turner AE. The efficacy of Adeli suit treatment in children with cerebral palsy.

Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology [Internet]. 2006; 48(5):[324- pp.]. Available from:

https://www.cambridge.org/core/article/efficacy-of-adeli-suit-treatment-in-children-with-cerebral-

palsy/75AFA67F81E658CD64D18773CC5E438E.

18.

Scheeren EM, Mascarenhas LPG, Chiarello CR, Costin ACMS, Oliveira L, Neves EB. Description

of the Pediasuit ProtocolTM. Fisioterapia em Movimento [Internet]. 2012; 25:[473-80 pp.]. Available

from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci arttext&pid=S0103-

51502012000300002&nrm=iso.

19.

Koscielny R. Strength training and CP. Available from:

http://www.suittherapy.com/download%20center/artilces/Strenght%20Training%20and%20CP.pdf.

20.

Liaqat S, Butt MS, Javaid HMW. Effects of Universal Exercise Unit Therapy on Sitting Balance

in Children with Spastic and Athetoid Cerebral Palsy: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Khyber Medical

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

31

Page 60 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

University Journal [Internet]. 2016; 8(4):[177- pp.]. Available from:

http://www.kmuj.kmu.edu.pk/article/view/16786.

21.

Emara HA, El-Gohary TM, Al-Johany AA. Effect of body-weight suspension training versus

treadmill training on gross motor abilities of children with spastic diplegic cerebral palsy. Eur J Phys

Rehabil Med [Internet]. 2016 Jun; 52(3):[356-63 pp.]. Available from:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26845668/.

22.

Menz SM, Hatten K, Grant-Beuttler M. Strength Training for a Child With Suspected

Developmental Coordination Disorder. Pediatric Physical Therapy [Internet]. 2013; 25(2). Available

from:

https://journals.lww.com/pedpt/Ful text/2013/25020/Strength Training for a Child With Suspect

ed.18.aspx.

23.

Bar-Haim S, Harries N, Belokopytov M, Frank A, Copeliovitch L, Kaplanski J, et al. Comparison

of efficacy of Adeli suit and neurodevelopmental treatments in children with cerebral palsy.

Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology [Internet]. 2006; 48(5):[325-30 pp.]. Available from:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1017/S0012162206000727.

24.

Nemkova SA, Kobrin VI, Sologubov EG, Iavorskiĭ AB, Sinel'nikova AN. [Regulation of vertical

posture in patients with children's cerebral paralysis treated with the method of proprioceptive

correction]. Aviakosm Ekolog Med [Internet]. 2000 2000; 34(6):[40-6 pp.]. Available from:

http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/11253723.

25.

Gracies J-M, Marosszeky JE, Renton R, Sandanam J, Gandevia SC, Burke D. Short-term effects

of dynamic Lycra splints on upper limb in hemiplegic patients. Archives of Physical Medicine and

Rehabilitation [Internet]. 2000 2000/12/01/; 81(12):[1547-55 pp.]. Available from:

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pi /S0003999300546231.

26.

Morris C, Bowers R, Ross K, Stevens P, Phillips D. Orthotic management of cerebral palsy:

recommendations from a consensus conference. NeuroRehabilitation [Internet]. 2011; 28(1):[37-46

pp.]. Available from: https://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/40443/1/ful text.pdf.

27.

Bailes AF, Greve K, Schmitt LC. Changes in Two Children with Cerebral Palsy After Intensive

Suit Therapy: A Case Report. Pediatric Physical Therapy [Internet]. 2010; 22(1). Available from:

https://journals.lww.com/pedpt/Ful text/2010/02210/Changes in Two Children with Cerebral Pa

lsy After.11.aspx.

28.

Neves EB, Krueger E, de Pol S, de Oliveira MCN, Szinke AF, de Oliveira Rosário M. Benefits of

intensive neuromotor therapy (TNMI) for the control of the trunk of children with cerebral palsy.

Neuroscience Magazine [Internet]. 2013; 21(4):[549-55 pp.]. Available from:

https://periodicos.unifesp.br/index.php/neurociencias/article/download/8141/5673.

29.

Datorre E. Intensive Therapy Combined with Strengthening Exercises Using the Thera Suit in

a child with CP: A Case Report. American Association of Intensive Pediatric Physical Therapy

[Internet]. 2005. Available from:

http://www.suittherapy.com/pdf%20research/Int.%20Therapy%20%20Research%20Datore.pdf.

30.

Semenova KA. Basis for a method of dynamic proprioceptive correction in the restorative

treatment of patients with residual-stage infantile cerebral palsy. Neuroscience and Behavioral

Physiology [Internet]. 1997 1997/11/01; 27(6):[639-43 pp.]. Available from:

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02461920.

31.

NAPA Centre. NeuroSuit 2020 [Available from: https://napacentre.com.au/our-

programs/neurosuit/.

32.

Ability Plus Therapy. Intensive suit therapy 2014 [Available from:

http://abilityplustherapy.com/got-therapy/intensive-suit-therapy/.

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

32

Page 61 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

33.

Karadağ-Saygı E, Giray E. The clinical aspects and effectiveness of suit therapies for cerebral

palsy: A systematic review. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil [Internet]. 2019; 65(1):[93-110 pp.]. Available

from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6648185/.

34.

Centre N. Cuevas Medek Exercise 2020 [Available from: https://napacentre.com.au/our-

programs/intensive-therapy/.

35.

Vanderminden JA. The social construction of disability and the modern-day healer 2009.

36.

de Oliveira GR, Fabris Vidal M. A normal motor development in congenital hydrocephalus

after Cuevas Medek Exercises as early intervention: A case report. Clinical Case Reports [Internet].

2020; 8(7):[1226-9 pp.]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ccr3.2860.

37.

Mitroi S. Stimulation of triple extension tone and orthostatic balance in the child with

cerebral palsy through exercises specific to medek method. PhysicalEducation, Sport and

KinesiologyJournal [Internet]. 2016; 1(43):[48-51 pp.]. Available from:

https://discobolulunefs.ro/Reviste/2016/Discobolul ful paper 43 1 2016 v2.pdf#page=47.

38.

Tanner K, Schmidt E, Martin K, Bassi M. Interventions Within the Scope of Occupational

Therapy Practice to Improve Motor Performance for Children Ages 0–5 Years: A Systematic Review.

American Journal of Occupational Therapy [Internet]. 2020; 74(2):[7402180060p1-p40 pp.].

Available from: https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.039644.

39.

Longo E, de Campos AC, Palisano RJ. Let's make pediatric physical therapy a true evidence-

based field! Can we count on you? Brazilian journal of physical therapy [Internet]. 2019 May-Jun;

23(3):[187-8 pp.]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6531638/.

40.

Sakzewski L, Ziviani J, Boyd RN. Efficacy of Upper Limb Therapies for Unilateral Cerebral

Palsy: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics [Internet]. 2014; 133(1):[e175-e204 pp.]. Available from:

https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/133/1/e175.full.pdf.

41.

Elgawish M, Zakaria M. The effectiveness of intensive versus standard physical therapy for

motor progress in children with spastic cerebral palsy. Egyptian Rheumatology and Rehabilitation

[Internet]. 2015 January 1, 2015; 42(1):[1-6 pp.]. Available from:

http://www.err.eg.net/article.asp?issn=1110-

161X;year=2015;volume=42;issue=1;spage=1;epage=6;aulast=Elgawish.

42.

Novak I, Cusick A, Lannin N. Occupational Therapy Home Programs for Cerebral Palsy:

Double-Blind, Randomized, Controlled Trial. Pediatrics [Internet]. 2009; 124(4):[e606-e14 pp.].

Available from: https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/124/4/e606.full.pdf.

43.

Lin K-c, Wang T-n, Wu C-y, Chen C-l, Chang K-c, Lin Y-c, et al. Effects of home-based

constraint-induced therapy versus dose-matched control intervention on functional outcomes and

caregiver well-being in children with cerebral palsy. Research in Developmental Disabilities

[Internet]. 2011 2011/09/01/; 32(5):[1483-91 pp.]. Available from:

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pi /S0891422211000242.

44.

Eliasson A-C, Shaw K, Berg E, Krumlinde-Sundholm L. An ecological approach of Constraint

Induced Movement Therapy for 2–3-year-old children: A randomized control trial. Research in

Developmental Disabilities [Internet]. 2011 2011/11/01/; 32(6):[2820-8 pp.]. Available from:

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pi /S089142221100196X.

45.

Hoare B, Imms C, Villanueva E, Rawicki HB, Matyas T, Carey L. Intensive therapy following

upper limb botulinum toxin A injection in young children with unilateral cerebral palsy: a randomized

trial. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology [Internet]. 2013; 55(3):[238-47 pp.]. Available

from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/dmcn.12054.

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

33

Page 62 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

46.

Rosenbaum PL, Walter SD, Hanna SE, Palisano RJ, Russell DJ, Raina P, et al. Prognosis for

Gross Motor Function in Cerebral PalsyCreation of Motor Development Curves. JAMA [Internet].

2002; 288(11):[1357-63 pp.]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.11.1357.

47.

Holmefur M, Krumlinde-Sundhold L, Bergstrom J, Eliasson A-C. Longitudinal development of

hand function in children with unilateral cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology

[Internet]. 2010; 52(4):[352-7 pp.]. Available from:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03364.x.

48.

Haley SM. Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory (PEDI): Development, standardization

and administration manual: Therapy Skill Builders; 1992.

49.

Palisano RJ, Hanna SE, Rosenbaum PL, Russell DJ, Walter SD, Wood EP, et al. Validation of a

Model of Gross Motor Function for Children With Cerebral Palsy. Physical Therapy [Internet]. 2000;

80(10):[974-85 pp.]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/80.10.974.

50.

Hanna SE, Bartlett DJ, Rivard LM, Russell DJ. Reference Curves for the Gross Motor Function

Measure: Percentiles for Clinical Description and Tracking Over Time Among Children With Cerebral

Palsy. Physical Therapy [Internet]. 2008; 88(5):[596-607 pp.]. Available from:

https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20070314.

51.

Bushby K, Finkel R, Birnkrant DJ, Case LE, Clemens PR, Cripe L, et al. Diagnosis and

management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: implementation of multidisciplinary care. The

Lancet Neurology [Internet]. 2010 2010/02/01/; 9(2):[177-89 pp.]. Available from:

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pi /S1474442209702728.

52.

Lurio JG, Peay HL, Mathews KD. Recognition and management of motor delay and muscle

weakness in children. Am Fam Physician [Internet]. 2015 Jan 1; 91(1):[38-44 pp.]. Available from:

https://www.aafp.org/afp/2015/0101/p38.html.

53.

Pascual JM. Progressive Brain Disorders in Childhood. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press; 2017.

54.

Jan MM, Shaabat AO. Clobazam for the treatment of intractable childhood epilepsy.

Neurosciences (Riyadh) [Internet]. 2000 Jul; 5(3):[159-61 pp.]. Available from:

http://www.nsj.org.sa/pdffiles/Jul00/Clobazam.pdf.

55.

Jan MM. Clinical approach to children with suspected neurodegenerative disorders.

Neurosciences [Internet]. 2002; 7(1):[2-6 pp.]. Available from:

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mohammed Jan/publication/227859386 Clinical approach

to children with suspected neurodegenerative disorders/links/09e414fe6f11164c36000000.pdf.

56.

Olney RS, Doernberg NS, Yeargin-Allsop M. Exclusion of progressive brain disorders of

childhood for a cerebral palsy monitoring system: a public health perspective. J Registry Manag

[Internet]. 2014 Winter; 41(4):[182-9 pp.]. Available from:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25803631.

57.

Christiansen AS, Lange C. Intermittent versus continuous physiotherapy in children with

cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology [Internet]. 2008; 50(4):[290-3 pp.].

Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.02036.x.

58.

Bower E, Michell D, Burnett M, Campbell MJ, McLellan DL. Randomized controlled trial of

physiotherapy in 56 children with cerebral palsy followed for 18 months. Developmental Medicine &

Child Neurology [Internet]. 2001; 43(1):[4-15 pp.]. Available from:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2001.tb00378.x.

59.

Almeida KM, Fonseca ST, Figueiredo PRP, Aquino AA, Mancini MC. Effects of interventions

with therapeutic suits (clothing) on impairments and functional limitations of children with cerebral

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

34

Page 63 of 153

FOI 24/25-0473

palsy: a systematic review. Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy [Internet]. 2017 2017/09/01/;

21(5):[307-20 pp.]. Available from:

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pi /S1413355517302484.

N A P A T h e r a p y R e s e a r c h

P a g e |

35

Page 64 of 153