DOCUMENT 2

Re

DOCUMENT 2

Re

FOI

search

23/24-1127,

Paper

1128 & 1134

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

Long COVID-19

The content of this document is OFFICIAL.

Please note:

The research and literature reviews collated by our TAB Research Team are not to be shared

external to the Branch. These are for internal TAB use only and are intended to assist our

advisors with their reasonable and necessary decision-making.

Delegates have access to a wide variety of comprehensive guidance material. If Delegates

require further information on access or planning matters, they are to call the TAPS line for

advice.

The Research Team are unable to ensure that the information listed below provides an

accurate & up-to-date snapshot of these matters

Research question: Based on latest research, would long covid be considered permanent

and what is the prognosis? What are the most effective treatments? What are the outcomes of

these treatments? What are the more common longer lasting effects? What is the prevalence

of long COVID-19?

Date: 15/07/22

Reviewed: 20/09/23

Requestor: s47F - personal privacy

Endorsed by (EL1 or above): s47F - personal privacy

Researcher: s47F - personal privacy

Cleared by: s47F - personal privacy

Reviewed by: s47F - personal privacy

Next review date: 18/09/24

V2.0 20-09-23

Long COVID-19

Page 1 of 14

OFFICIAL

Page 13 of 26

Re

Re

FOI

search

23/24-1127,

Paper

1128 & 1134

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

1. Contents

Long COVID-19 ...................................................................................................................... 1

1.

Contents ....................................................................................................................... 2

2.

Summary ...................................................................................................................... 2

3.

Review, September 2023 .............................................................................................. 3

3.1

Prolonged disability ....................................................................................................... 3

3.2

Treatment and management ......................................................................................... 3

4.

What is long COVID-19? ............................................................................................... 4

5.

What is the prevalence of long COVID-19? .................................................................. 5

6.

What are the most common symptoms of long COVID-19? ......................................... 5

7.

What is the current management for long COVID-19? .................................................. 6

8.

Permanence of long COVID-19 .................................................................................... 8

9.

References ................................................................................................................. 11

10.

Version control ............................................................................................................ 14

2. Summary

Update (September, 2023): Heterogeneity of research data is still a significant barrier to

determining the prevalence and incidence of long COVID, the persistence of disability

associated with long COVID and any effective treatment and management techniques.

Estimates of activity limitation for people with long COVID vary between 16% and 80%.

Estimates of prevalence vary considerably, though studies coalesce around estimates in the

range of either 10%-20% or 40%-55%. The evidence base for treatment and management

techniques is growing with some evidence supporting physical therapy, multimodal and

personalised approaches. No pharmacological or non-pharmacological technique has

emerged as a preferred pathway.

Long COVID-19 is a collection of symptoms that persist after the initial acute phase of COVID-

19 infection. While some consider 4 weeks the start of prolonged symptomology, 12 weeks is

emerging as the point where long COVID-19 can be diagnosed. The prevalence of long

COVID-19 is difficult to determine due to heterogeneity in the research data, however it is

suggested to effect between 10-20% of people who survive a COVID-19 infection.

Management of long COVID-19 will likely follow the management protocols for other post-viral

syndromes, such as myalgic encephalitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, or critical illness recovery

paths, for example post-intensive care syndrome.

V2.0 20-09-23

Long COVID-19

Page 2 of 14

OFFICIAL

Page 14 of 26

Re

Re

FOI

search

23/24-1127,

Paper

1128 & 1134

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

Permanence of long COVID-19 is difficult to determine at this point as the disease is in its

infancy, however most people are expected to make a recovery over many months.

Nonetheless, it is expected some people will continue to have physical and/or mental

impairment that significantly impacts their functional capacity. As a consequence, the United

States Department of Health and Human Services advises that long COVID-19 can be

considered a disability after patients complete an individualised assessment that indicates they

have severely impaired functional capacity.

3. Review, September 2023

3.1 Prolonged disability

Estimates of prevalence and incidence of long COVID, and estimates of the presence of

impairment or activity limitation still vary widely. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

found approximately one quarter of adults with long COVID report significant activity limitations

(Ford et al, 2023). Reviewing 35 studies, Oliveira-Almeida et al (2023) found activity limitations

in between 16% and 80% of subjects.

The World Health Organisation still endorses a prevalence estimate of 10-20% (WHO, 2022).

Woodrow et al (2023) reviewed 73 studies and found prevalence estimates between 0% and

93%. An international systematic review considered 194 studies including 735,006 participants

and found 45% of COVID-19 survivors experience ongoing symptoms at 4 months

(O’Mahoney et al, 2022). In a review involving 120,970 patients, Di Gennaro et al (2023) found

an incidence of 56.9%. In contrast, 10 longitudinal studies from the UK found continuation of

symptoms after 12 weeks in 8-17% of cases (Hallek et al, 2023). Hallek et al (2023) found

15% of unvaccinated adults infected with SARS-CoV-2 met criteria for post-COVID syndrome,

with lower incidence among vaccinated COVID-19 survivors. Evidence from the US also

supports the rate of around 15%. Between 14% and 16% of respondents to the Household

Pulse Survey report experiencing long COVID (National Centre for Health Statistics, 2023).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found approximately 16% of adults with COVID-

like symptoms reported ongoing symptoms after 12 months (Montoy et al, 2023). In contrast,

Woodrow et al (2023) found prevalence estimate of 48.5% after 12 months. Woodrow et al

conclude that the way in which long COVID is defined and measured affects prevalence

estimates. Estimates are lower in studies using routine health records (13.6%) compared with

self-report studies (43.9%). The highest estimates were found in studies systematically

investigating pathology (51.7%).

3.2 Treatment and management

No pharmacological or non-pharmacological treatment or management strategy has emerged

as the favoured method among researchers or clinicians (Chandon et al, 2023; Chee et al,

2023; Fawzy et al, 2023; Marshall-Andon et al, 2023; Hallek et al, 2023).

V2.0 20-09-23

Long COVID-19

Page 3 of 14

OFFICIAL

Page 15 of 26

Re

Re

FOI

search

23/24-1127,

Paper

1128 & 1134

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

In their review of 37 practice guidelines, Marshall-Andon et al (2023) found some consensus

around education, shared decision making and personalised care for patients with long

COVID, including tailoring the modality and setting of treatment or management to the

patient’s situation.

A recent review of 12 studies found physical therapy (especially, moderate exercise and

interventions related to respiratory muscles) was associated with a significant improvement in

fatigue, dyspnea and quality of life in patients with long COVID (Sánchez-García et al, 2023).

4. What is long COVID-19?

There is no internationally agreed definition of long COVID-19, however signs and symptoms

beyond 4 weeks is considered ongoing COVID-19 (Molhave et al, 2022). The World Health

Organisation (WHO) recognised the existence of continuing symptoms and effects of COVID-

19 after the initial infection period in September 2020, stating long COVID-19 is:

an illness that occurs in people who have a probable or confirmed SARS-CoV-2

infection; usually within 3 months of onset of the infection, with symptoms and effects

that last for at least 3 months. These symptoms and effects cannot be explained by an

alternative diagnosis (WHO, 2021a).

In the United States, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advise that post-

COVID-19 conditions can be identified at least 4 weeks after the initial COVID-19 diagnosis

(CDC, 2022). In the United Kingdom, the National Institute for Health Care and Excellence

(NICE) proposes that ‘acute COVID-19' is the period up to 4 weeks post infection diagnosis,

‘COVID in progress’ is the experience of signs and symptoms between 4-12 weeks post

infection diagnosis, and post-COVID-19 syndrome are signs and symptoms that continue for

more than 12 weeks after the initial infection and are not attributable to another diagnosis

(NICE, 2022). A formal definition of long COVID-19 by the Australian Health Department could

not be found.

The CDC suggests long COVID-19 is more common for people who had severe symptoms of

COVID-19 during their initial infection (CDC, 2022), however the WHO advise there is no clear

evidence of a relationship between initial severity of COVID-19 infection and the likelihood of

developing long COVID-19 (WHO, 2021b). What is known, is people can suffer long COVID-

19 regardless of whether they had mild or severe symptoms with the initial COVID-19 infection

(Berger et al, 2021).

While research is continuing to try to identify those most at risk of long COVID-19, some risk

factors may include (Berger et al, 2021; CDC, 2022):

• people who were in intensive care units during their initial COVID-19 infection

• people who have underlying health conditions prior to the infection including

diabetes, heart failure, asthma, hypertension and epilepsy

V2.0 20-09-23

Long COVID-19

Page 4 of 14

OFFICIAL

Page 16 of 26

Re

Re

FOI

search

23/24-1127,

Paper

1128 & 1134

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

• demographics with health inequities such as ethnic minority groups and people with

disability

• people unvaccinated against COVID-19

• adults appear more vulnerable to long COVID-19 than children.

5. What is the prevalence of long COVID-19?

Despite the body of research emerging around long COVID-19, the prevalence is difficult to

determine due to differences in study methodology, different outcome definitions and time

frames, and different symptoms and levels of severity surveyed (Emecen et al, 2022).

Additionally, prevalence is influenced by social determinants, such as poverty, racism and

disability (Berger et al, 2021), therefore there is considerable inconsistency in the literature

depending on participant demographics.

In one United Kingdom study, 18.2% of participants reported at least one symptom 6 months

post initial COVID-19 infection (Emecen et al, 2022). This is in line with the WHO (2021b)

estimate that around 10-20% of COVID-19 survivors experience mid- and long-term effects

after the acute phase of illness has passed. However, a systematic review cited by Maglietta et

al (2022), involving 57 studies and over 250,000 survivors of COVID-19, demonstrated more

than half of these survivors experienced post-acute symptoms at 6 months post initial

infection. I was unable to source clear data for the persistence of symptoms beyond this time

point.

Further complicating prevalence data is the influence of different variants on recovery from

COVID-19. Research from the United Kingdom comparing the Delta and Omicron variants

suggests an increased risk of ongoing symptoms at 4 weeks post infection with Delta infection

(10.8% participants) than an Omicron infection (4.5% participants) (Antonelli et al, 2022).

6. What are the most common symptoms of long COVID-

19?

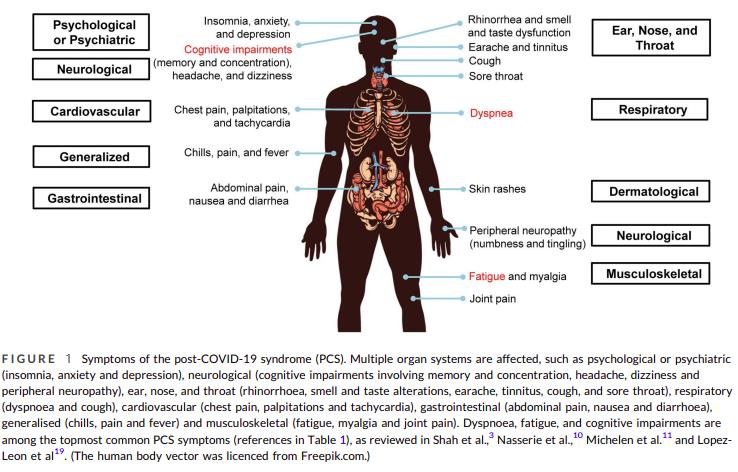

It has been noted that symptoms of long COVID-19 are similar to other post-viral fatigue

syndromes such as myalgic encephalitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (Boaventrua et al, 2022;

CDC, 2022), although the multisystem complications from long COVID-19 maybe broader and

more intense than other post-viral syndromes (Boaventrua et al, 2022).

The most common symptoms of long COVID-19 reported in the literature include (Berger et al,

2021; CDC, 2022; Maglietta et al, 2022; Scordo et al, 2021; WHO, 2021b):

• Physical and mental fatigue that interferes with daily life

• Shortness of breath

• Memory and concentration problems (‘brain fog’)

V2.0 20-09-23

Long COVID-19

Page 5 of 14

OFFICIAL

Page 17 of 26

Re

Re

FOI

search

23/24-1127,

Paper

1128 & 1134

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

• Headache

• Mental health impairment (e.g., anxiety, depression, mood swings)

• Abdominal pains

• Muscle weakness and joint pain

• Palpitations and chest pain

• Dizziness

• Gastrointestinal issues (e.g., diarrhea, stomach pain)

• Sleep problems

• Change in smell and/or taste

• Pins and needles feeling

• Skin lesions similar to chilblains

Long COVID-19 may affect people differently as different organ systems become involved, and

an individual’s symptoms may fluctuate or relapse over time (Berger et al, 2021; WHO,

2021b).

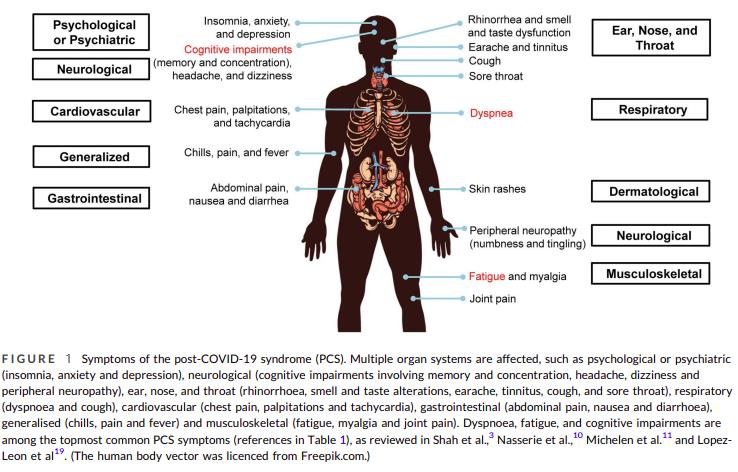

Figure 1 below, an excerpt from research by Yong and Liu (2021), highlights the different

organ systems that may be affected by long COVID-19:

7. What is the current management for long COVID-19?

V2.0 20-09-23

Long COVID-19

Page 6 of 14

OFFICIAL

Page 18 of 26

Re

Re

FOI

search

23/24-1127,

Paper

1128 & 1134

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

There is no documented specific medication to treat long COVID-19 (Molhave et al, 2022) and

much of the current literature describes medical management of long COVID-19. Effective

management of long COVID-19 involves symptom relief and rehabilitation (Molhave et al,

2022; WHO, 2021b), and involvement of a multidisciplinary team for patients with multiple

organ systems impacted may be required (Berger et al, 2021; Kokhan et al, 2022; Molhave et

al, 2022; Scordo et al, 2021; Sundar Srethstha & Love, 2021).

Particular rehabilitation programs mentioned in the literature include physical rehabilitation to

improve respiratory and cardiovascular function, which is best performed within 2 months of

initial diagnosis of COVID-19 (Kokhan et al, 2022; Molhave et al, 2022). Also, cognitive

therapy has been shown to be effective for patients with mental fatigue (Molhave et al, 2022).

As the existence of long COVID-19 is in its infancy, there is speculation, for example by Dr

Anthony Fauci of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, that long COVID-19

may have a similar aetiology to other post-infectious conditions such as myalgic

encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (Scordo et al, 2021; Sundar Shrestha & Love,

2021). Therefore, exploring the aetiology and management of myalgic

encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome may give some insight into long COVID-19

syndrome (Scordo et al, 2021). Current literature indicates cognitive behaviour therapy and

graded exercise therapy are important in the management of myalgic encephalitis/chronic

fatigue syndrome (Sharpe et al, 2021; Snook & Slowman, 2019). Cognitive behaviour therapy

focusses on challenging fatigue related cognitions and planning social and occupational

rehabilitation, while graded exercise therapy involves determining baseline ability and slowly

increasing intensity and duration without exacerbating symptoms (Sharpe et al, 2021; Snook &

Slowman, 2019).

Another significant medical condition that may be relevant to the understanding and

management of long COVID-19 is post-intensive care syndrome (PICS) - the presence of

health problems common to patients who have recovered from critical illness in intensive care

units (Parker et al, 2021). Similar to long COVID-19, cognitive impairment ('brain fog’), extreme

fatigue, muscle weakness, and shortness of breath are among the most common symptoms of

PICS (Parker et al, 2021). Parker et al (2021) suggests applying the PICS post-acute phase

framework to long COVID-19 patients could involve:

• Occupational therapy – provide energy conservation and work simplification strategies;

address impact of cognitive impairments on work performance; monitor for residual

impairment in gross and fine motor function, sensory integration or pain related to

positioning (such as prolonged proning in ICU); strengthening and fine motor training

using writing aids or assistive technology.

• Physical therapy – ICU acquired weakness can persist for years after the acute illness

has resolved, therefore physical therapy can be beneficial to improve strength and

physical function.

V2.0 20-09-23

Long COVID-19

Page 7 of 14

OFFICIAL

Page 19 of 26

Re

Re

FOI

search

23/24-1127,

Paper

1128 & 1134

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

• Speech therapy – intubation injuries can extend from the voice and airway to

dysphagia; dysphagia can persist for months, but most patients will recover with

support.

• Social workers – many patients report persistent symptoms that impact their ability to

return to work. Social workers can connect patients with job resources, conduct

screening for mental health impairments, and provide psychoeducation and referrals.

• Primary health care – primary health practitioners should provide aftercare and care

coordination for long COVID-19 patients.

8. Permanence of long COVID-19

For most people, the natural history of long COVID-19 appears to be a gradual improvement of

symptoms over many months (Berger et al, 2021; CDC, 2022; WHO, 2021b). However, the

long-term prognosis for some people is unknown, as it is not known whether damaged organ

systems will fully recover or if there will be lasting effects (Berger et al, 2021; Scordo et al,

2021). Unfortunately, it appears some people with long COVID-19 will continue to have long-

term organ compromise, long-term complex immune and homeostatic dysfunction with

disabling symptoms and impaired functional levels (Sundar Srethstha & Love, 2021).

In July 2021, long COVID-19 became a recognised disability under the Americans with

Disabilities Act, Section 504 and Section 1557 (CDC, 2022; United States Department of

Health and Human Services, 2021). In the United States, as long COVID-19 causes physical

and/or mental impairment, it can be considered a disability if it substantially limits one or more

major life activities such as caring for oneself, performing manual tasks, eating, walking or

concentrating. Table 1 summarises further information from the United States Department of

Health and Human Services (2021) regarding long COVID-19 as a disability.

However, whether long COVID-19 can be considered a permanent disability requires an

individualised assessment to determine if the long COVID-19 symptoms and effects

substantially impact the individual’s functional capacity (United States Department of Health

and Human Services, 2021).

Table 1

Information regarding long COVID-19 as a disability (United States Department of Health and

Human Services, 2021)

ADA, Section 504, and Section 1557 if it substantially limits one or more major life activities.

These laws and their related rules define a person with a disability as an individual with a

physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more of the major life activities

of such individual (“actual disability”); a person with a record of such an impairment (“record

of”); or a person who is regarded as having such an impairment (“regarded as”). A person

V2.0 20-09-23

Long COVID-19

Page 8 of 14

OFFICIAL

Page 20 of 26

Re

Re

FOI

search

23/24-1127,

Paper

1128 & 1134

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

with long COVID has a disability if the person’s condition or any of its symptoms is a

“physical or mental” impairment that “substantially limits” one or more major life activities.

a. Long COVID is a physical or mental impairment.

A physical impairment includes any physiological disorder or condition affecting one or more

body systems, including, among others, the neurological, respiratory, cardiovascular, and

circulatory systems. A mental impairment includes any mental or psychological disorder,

such as an emotional or mental illness.

Long COVID is a physiological condition affecting one or more body systems. For example,

some people with long COVID experience:

• Lung damage

• Heart damage, including inflammation of the heart muscle

• Kidney damage

• Neurological damage

• Damage to the circulatory system resulting in poor blood flow

• Lingering emotional illness and other mental health conditions

Accordingly, long COVID is a physical or mental impairment under the ADA, Section 504,

and Section 1557.

b. Long COVID can substantially limit one or more major life activities

“Major life activities” include a wide range of activities, such as caring for oneself, performing

manual tasks, seeing, hearing, eating, sleeping, walking, standing, sitting, reaching, lifting,

bending, speaking, breathing, learning, reading, concentrating, thinking, writing,

communicating, interacting with others, and working. The term also includes the operation of

a major bodily function, such as the functions of the immune system, cardiovascular system,

neurological system, circulatory system, or the operation of an organ.

The term “substantially limits” is construed broadly under these laws and should not demand

extensive analysis. The impairment does not need to prevent or significantly restrict an

individual from performing a major life activity, and the limitations do not need to be severe,

permanent, or long-term. Whether an individual with long COVID is substantially limited in a

major bodily function or other major life activity is determined without the benefit of any

medication, treatment, or other measures used by the individual to lessen or compensate for

symptoms. Even if the impairment comes and goes, it is considered a disability if it would

substantially limit a major life activity when the impairment is active.

Long COVID can substantially limit a major life activity. The situations in which an individual

with long COVID might be substantially limited in a major life activity are diverse. Among

possible examples, some include:

V2.0 20-09-23

Long COVID-19

Page 9 of 14

OFFICIAL

Page 21 of 26

Re

Re

FOI

search

23/24-1127,

Paper

1128 & 1134

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

• A person with long COVID who has lung damage that causes shortness of breath,

fatigue, and related effects is substantially limited in respiratory function, among other

major life activities

• A person with long COVID who has symptoms of intestinal pain, vomiting, and

nausea that have lingered for months is substantially limited in gastrointestinal

function, among other major life activities

• A person with long COVID who experiences memory lapses and “brain fog” is

substantially limited in brain function, concentrating, and/or thinking.

V2.0 20-09-23

Long COVID-19

Page 10 of 14

OFFICIAL

Page 22 of 26

Re

Re

FOI

search

23/24-1127,

Paper

1128 & 1134

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

9. References

Antonelli, M., Pujol, J. C., Spector, T. D., Ourselin, S., & Steves, C. J. (2022). Risk of long

COVID associated with delta versus omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2.

Lancet (London,

England),

399(10343), 2263–2264. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00941-2

Berger, Z., Altiery de Jesus, V., Assoumou, S. A. & Greenhalgh, T. (2021). Long COVID and

health inequities: The role of primary care.

The Milbank Quarterly, 99(2), 519-541.

https://doi.org/10.1111%2F1468-0009.12505

Boaventura, P., Macedo, S., Ribeiro, F., Jaconiano, S., & Soares, P. (2022). Post-COVID-19

condition: where are we now?

Life, 12(4), 517. https://doi.org/10.3390/life12040517

Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022).

Long COVID or Post-COVID Conditions.

Accessed from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-term-effects/index.html

Chandan, J. S., Brown, K. R., Simms-Williams, N., Bashir, N. Z., Camaradou, J., Heining, D.,

Turner, G. M., Rivera, S. C., Hotham, R., Minhas, S., Nirantharakumar, K., Sivan, M.,

Khunti, K., Raindi, D., Marwaha, S., Hughes, S. E., McMullan, C., Marshall, T., Calvert,

M. J., Haroon, S., … TLC Study (2023). Non-Pharmacological Therapies for Post-Viral

Syndromes, Including Long COVID: A Systematic Review.

International journal of

environmental research and public health,

20(4), 3477.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043477

Chee, Y. J., Fan, B. E., Young, B. E., Dalan, R., & Lye, D. C. (2023). Clinical trials on the

pharmacological treatment of long COVID: A systematic review.

Journal of medical

virology,

95(1), e28289. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.28289

de Oliveira Almeida, K., Nogueira Alves, I. G., de Queiroz, R. S., de Castro, M. R., Gomes, V.

A., Santos Fontoura, F. C., Brites, C., & Neto, M. G. (2023). A systematic review on

physical function, activities of daily living and health-related quality of life in COVID-19

survivors.

Chronic illness,

19(2), 279–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/17423953221089309

Emecen, A. N., Keskin, S., Turunc, O., Suner, A. F., Siyve, N., Basoglu Sensoy, E., Dinc, F.,

Kilinc, O., Avkan Oguz, V., Bayrak, S., & Unal, B. (2022). The presence of symptoms

within 6 months after COVID-19: a single-center longitudinal study.

Irish Journal of

Medical Science, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-022-03072-0

Fawzy, N. A., Abou Shaar, B., Taha, R. M., Arabi, T. Z., Sabbah, B. N., Alkodaymi, M. S.,

Omrani, O. A., Makhzoum, T., Almahfoudh, N. E., Al-Hammad, Q. A., Hejazi, W.,

Obeidat, Y., Osman, N., Al-Kattan, K. M., Berbari, E. F., & Tleyjeh, I. M. (2023). A

systematic review of trials currently investigating therapeutic modalities for post-acute

COVID-19 syndrome and registered on WHO International Clinical Trials Platform.

Clinical microbiology and infection,

29(5), 570–577.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2023.01.007

V2.0 20-09-23

Long COVID-19

Page 11 of 14

OFFICIAL

Page 23 of 26

Re

Re

FOI

search

23/24-1127,

Paper

1128 & 1134

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

Ford N.D., Slaughter D., Edwards D., Dalton, A., {errine, C., Vahratian, A., & Saydah, S.

(2023). Long COVID and Significant Activity Limitation Among Adults, by Age — United

States, June 1–13, 2022, to June 7–19, 2023.

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report,

72(32), 866–870. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7232a3

Hallek, M., Adorjan, K., Behrends, U., Ertl, G., Suttorp, N., & Lehmann, C. (2023). Post-COVID

Syndrome.

Deutsches Arzteblatt international,

120(4), 48–55.

https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.m2022.0409

Kokhan, S., Vlasava, S., Kolokoltsev, M., Bayankin, O., Kispayev, T., Tromfimova, N., Suslina,

I., & Romanova, E. (2022). Postcovid physical rehabilitation at the sanatorium.

Journal

of Physical Education and Sport, 22(3), Art 76, 607-613. DOI:10.7752/jpes.2022.03076

Maglietta, G., Diodati, F., Puntoni, M., Lazzarelli, S., Marcomini, B., Patrizi, L., & Caminiti, C.

(2022). Prognostic Factors for Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: A Systematic Review and

Meta-Analysis.

Journal of clinical medicine,

11(6), 1541.

https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11061541

Marshall-Andon, T., Walsh, S., Berger-Gillam, T., & Pari, A. A. A. (2023). Systematic review of

post-COVID-19 syndrome rehabilitation guidelines. Integrated healthcare journal, 4(1),

e000100. https://doi.org/10.1136/ihj-2021-000100

Mølhave, M., Agergaard, J., & Wejse, C. (2022). Clinical Management of COVID-19 Patients -

An Update.

Seminars in nuclear medicine,

52(1), 4–10.

https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2021.06.004

Montoy, J. C. C. (2023). Prevalence of Symptoms≤ 12 Months After Acute Illness, by COVID-

19 Testing Status Among Adults—United States, December 2020–March 2023.

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report,

72(32), 859-865.

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/wr/mm7232a2.htm

National Centre for Health Statistics. (2023). Long COVID – Household Pulse Survey 2022-

2023. US Census Bureau. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/long-covid.htm.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2022).

COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing

the long-term effects of COVID-19. Accessed from

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188/resources/covid19-rapid-guideline-managing-

the-longterm-effects-of-covid19-pdf-51035515742

O'Mahoney, L. L., Routen, A., Gillies, C., Ekezie, W., Welford, A., Zhang, A., Karamchandani,

U., Simms-Williams, N., Cassambai, S., Ardavani, A., Wilkinson, T. J., Hawthorne, G.,

Curtis, F., Kingsnorth, A. P., Almaqhawi, A., Ward, T., Ayoubkhani, D., Banerjee, A.,

Calvert, M., Shafran, R., … Khunti, K. (2022). The prevalence and long-term health

effects of Long Covid among hospitalised and non-hospitalised populations: A

systematic review and meta-analysis.

EClinicalMedicine, 55, 101762.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101762

V2.0 20-09-23

Long COVID-19

Page 12 of 14

OFFICIAL

Page 24 of 26

Re

Re

FOI

search

23/24-1127,

Paper

1128 & 1134

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

Parker, A. M., Brigham, E., Connolly, B., McPeake, J., Agranovich, A. V., Kenes, M. T., Casey,

K., Reynolds, C., Schmidt, K., Kim, S. Y., Kaplin, A., Sevin, C. M., Brodsky, M. B., &

Turnbull, A. E. (2021). Addressing the post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection: a

multidisciplinary model of care.

The Lancet. Respiratory medicine,

9(11), 1328–1341.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00385-4

Sánchez-García, J. C., Rentero Moreno, M., Piqueras-Sola, B., Cortés-Martín, J., Liñán-

González, A., Mellado-García, E., & Rodriguez-Blanque, R. (2023). Physical Therapies

in the Treatment of Post-COVID Syndrome: A Systematic Review.

Biomedicines,

11(8),

2253. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11082253

Scordo, K. A., Richmond, M. M., & Munro, N. (2021). Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: Theoretical

Basis, Identification, and Management.

AACN advanced critical care,

32(2), 188–194.

https://doi.org/10.4037/aacnacc2021492

Sharpe, M., Chalder, T., & White, P. D. (2022). Evidence-Based Care for People with Chronic

Fatigue Syndrome and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis.

Journal of general internal medicine,

37(2), 449–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07188-4

Snook, A., & Slowman, L. (2019). Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Occupational Therapy.

CINAHL

Rehabilitation Guide.

Sundar Shrestha, D., & Love, R. (2021). Long COVID Patient Symptoms and its Evaluation

and Management.

JNMA; journal of the Nepal Medical Association,

59(240), 823–831.

https://doi.org/10.31729/jnma.6355

United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2021).

Guidance on “Long COVID”

as a disability under the ADA., Section 504, and Section 1557. United States of America

Government. Accessed from https://www.hhs.gov/civil-rights/for-providers/civil-rights-

covid19/guidance-long-covid-disability/index.html#footnote10_0ac8mdc

Woodrow, M., Carey, C., Ziauddeen, N., Thomas, R., Akrami, A., Lutje, V., Greenwood, D. C.,

& Alwan, N. A. (2023). Systematic Review of the Prevalence of Long COVID.

Open

forum infectious diseases,

10(7), ofad233. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofad233

World Health Organisation. (2022, December). Post COVID-19 condition (Long COVID) [Fact

sheet]. https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition

World Health Organisation. (2021a).

A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a

Delphi consensus, 6 October 2021. Accessed from

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post_COVID-19_condition-

Clinical case definition-2021.1

World Health Organisation. (2021b).

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Post COVID-19

condition. Accessed from https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-

answers/item/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-post-covid-19-condition

V2.0 20-09-23

Long COVID-19

Page 13 of 14

OFFICIAL

Page 25 of 26