FOI 24/25-0380

Literature Review

DOCUMENT 9

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

Diagnoses of Autism Spectrum Disorder using

the DSM-5

The content of this document is OFFICIAL.

Please note:

The research and literature reviews collated by our TAB Research Team are not to be

shared external to the Branch. These are for internal TAB use only and are intended to

assist our advisors with their reasonable and necessary decision-making.

Delegates have access to a wide variety of comprehensive guidance material. If

Delegates require further information on access or planning matters they are to call the

TAPS line for advice.

The Research Team are unable to ensure that the information listed below provides an

accurate & up-to-date snapshot of these matters

Research questions:

1. What is the accuracy of Autism Spectrum Disorder diagnoses using the DSM 5,

particulary for ASD levels 2 and 3 and particularly focussing on the interrater reliability of

single discipline assessments?

2. What is the incidence of ASD diagnosis among family members? How likely is it that

multiple siblings in a family will all have Autism Spectrum Disorder?

3. How has the rate of diagnosis of ASD changed since the publication of the DSM 5

diagnostic criteria?

Date: 10/12/2021

Requestor: S47F - Personal

Privacy

Endorsed by (EL1 or above): S47F - Personal

Privacy

Cleared by:

S47F - Personal

Privacy

1. Contents

Diagnoses of Autism Spectrum Disorder using the DSM-5 ........................................................ 1

1.

Contents ....................................................................................................................... 1

2.

Summary ...................................................................................................................... 2

3.

Frequency of ASD diagnoses in families ...................................................................... 2

4.

Accuracy and inter-rater reliability of ASD diagnoses using DSM-5.............................. 3

V0.1 10-12-21

ASD diagnoses

Page 1 of 20

OFFICIAL

Page 1 of 20

FOI 24/25-0380

Literature Review

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

5.

Influence of DSM-5 ASD criteria on the prevalence of ASD ......................................... 4

6.

Literature Summary ...................................................................................................... 6

7.

References ................................................................................................................. 19

8.

Version control ............................................................................................................ 20

2. Summary

This literature review addresses questions relating to the prevalence of Autism Spectrum

Disorder (ASD). Findings include:

• ASD is strongly genetic. If someone has a family with ASD it is more likely that they

will be diagnosed with ASD and it is more likely they will display autistic traits even if

they don’t meet the threshold for a diagnosis.

• DSM-5 diagnoses of ASD are overall more accurate than DSM-IV diagnoses. A true

positive diagnosis is more likely if multiple assessment tools are used in the context

of a multi-disciplinary team.

• The changes to DSM-5 ASD criteria likely reduced the frequency of ASD diagnoses,

although prevalence continues to rise as a result of other factors.

These findings are provisional and may be altered with further research. Evidence supporting

the high heritability of ASD is strong. Evidence is less reliable for prevalence estimates and

accuracy of diagnoses. There is significant effort to understand the prevalence of ASD

worldwide and to understand the effect of changes to the DSM-5 criteria. However, current

studies are often marred by bias, lack of controls and smal or unrepresentative samples. That

being said, there is wide-spread consensus in the literature around the above findings.

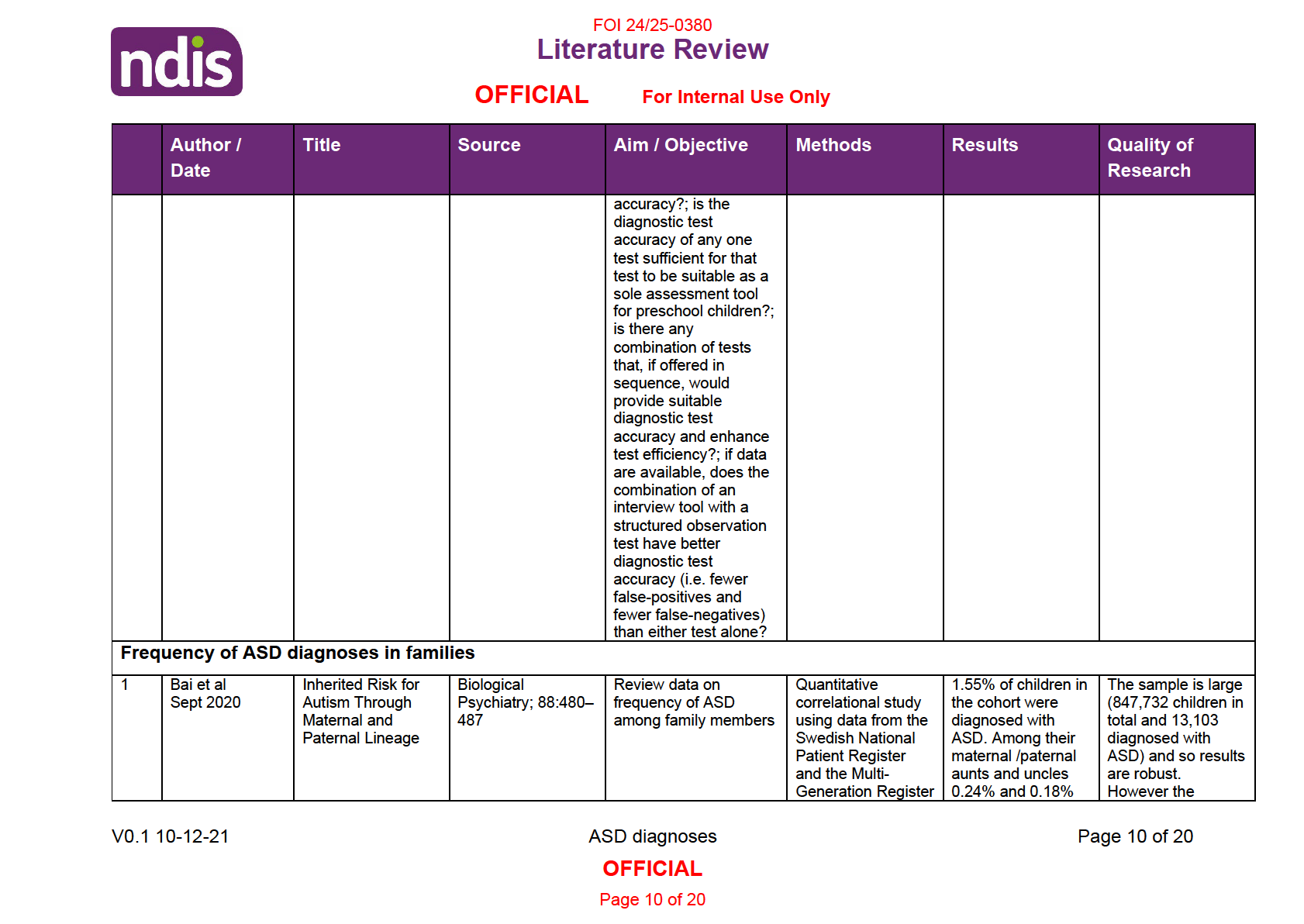

3. Frequency of ASD diagnoses in families

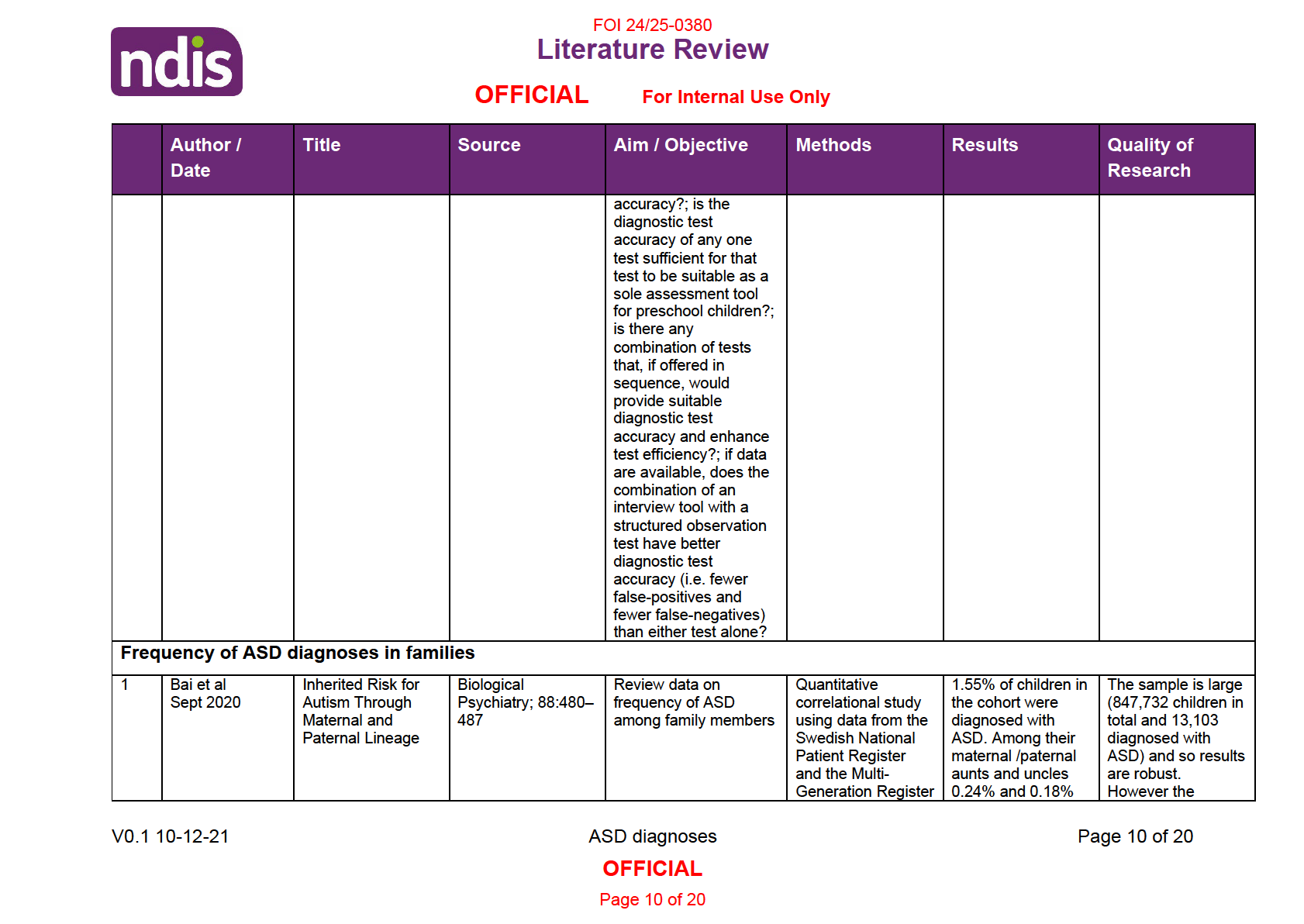

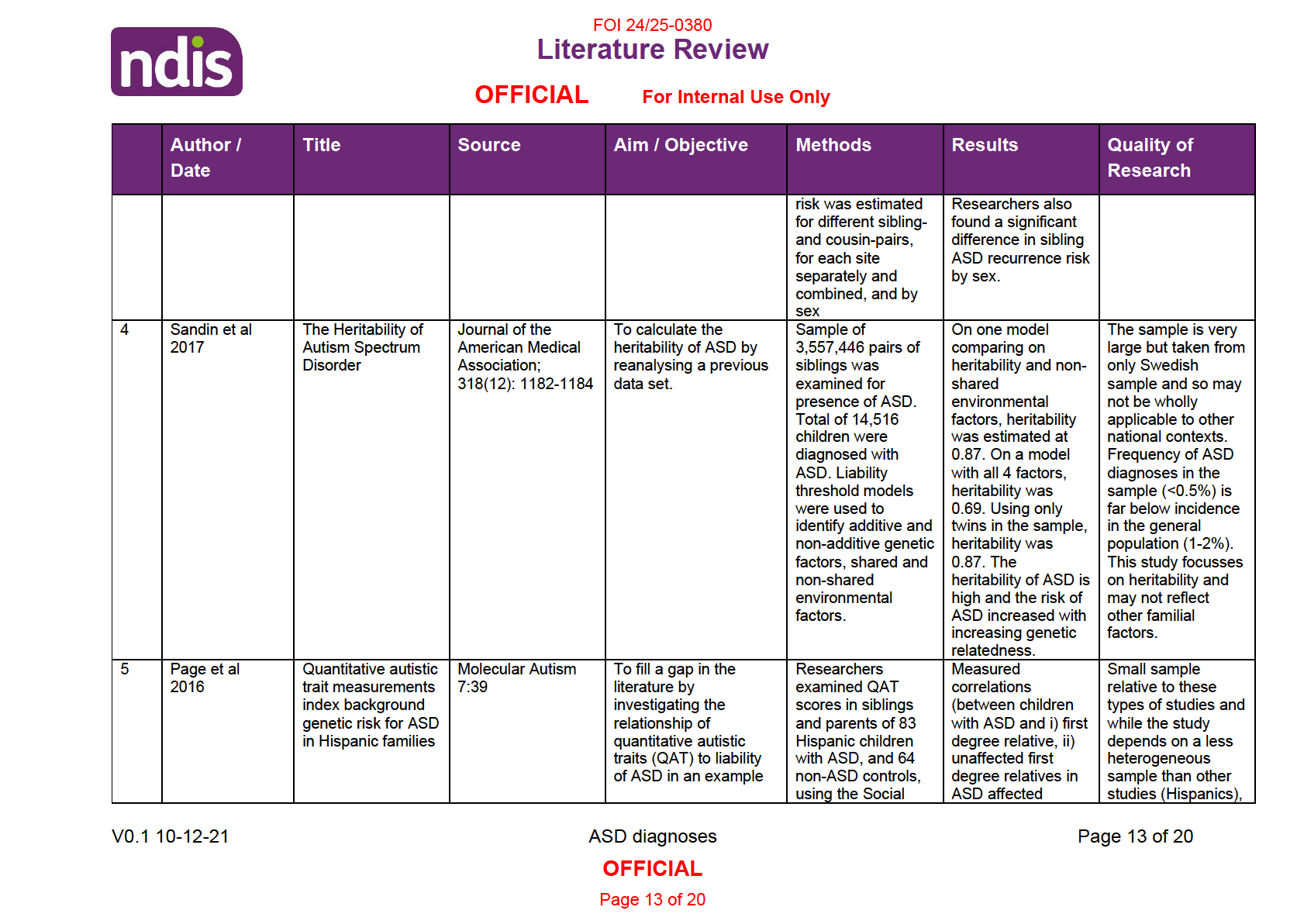

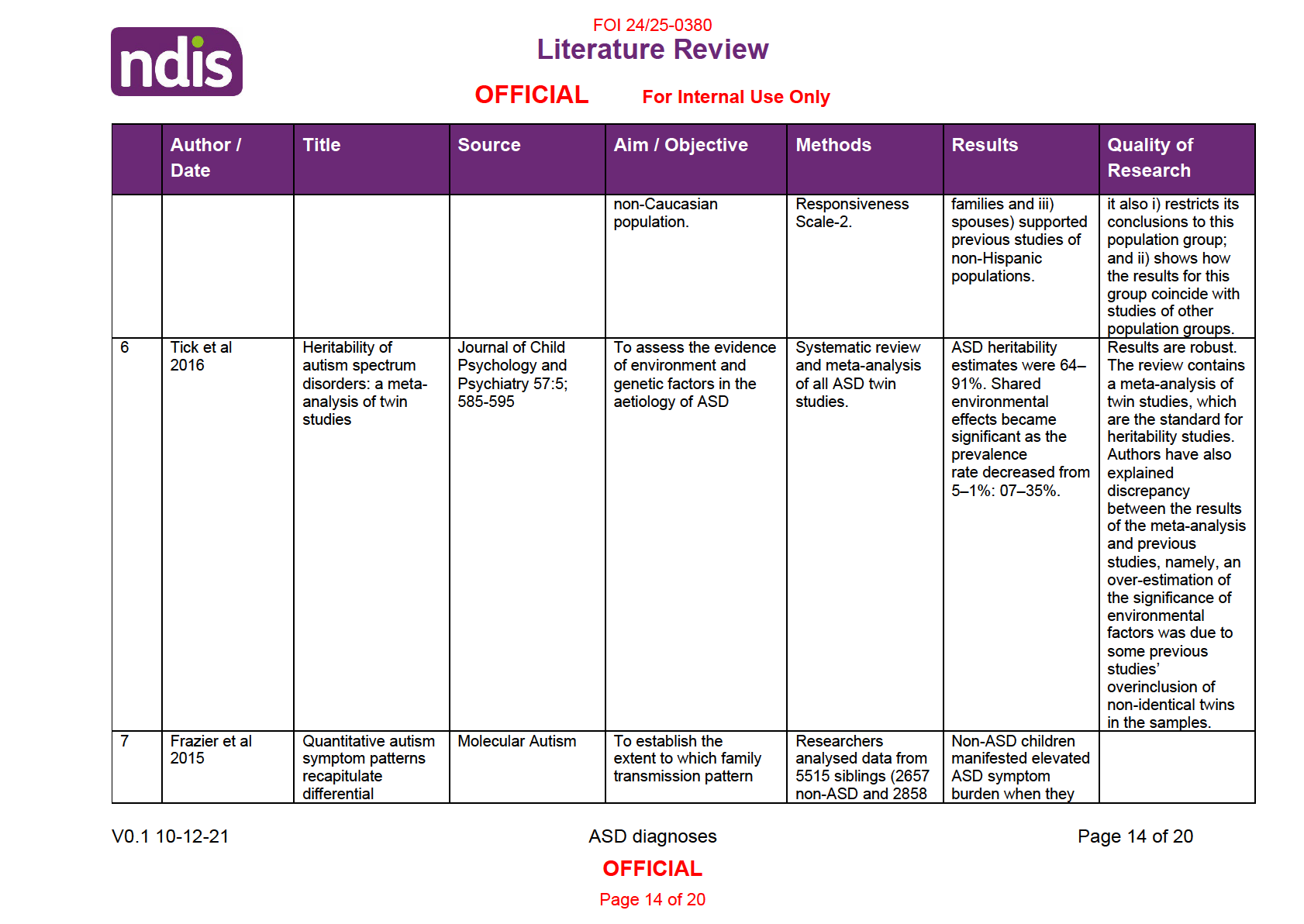

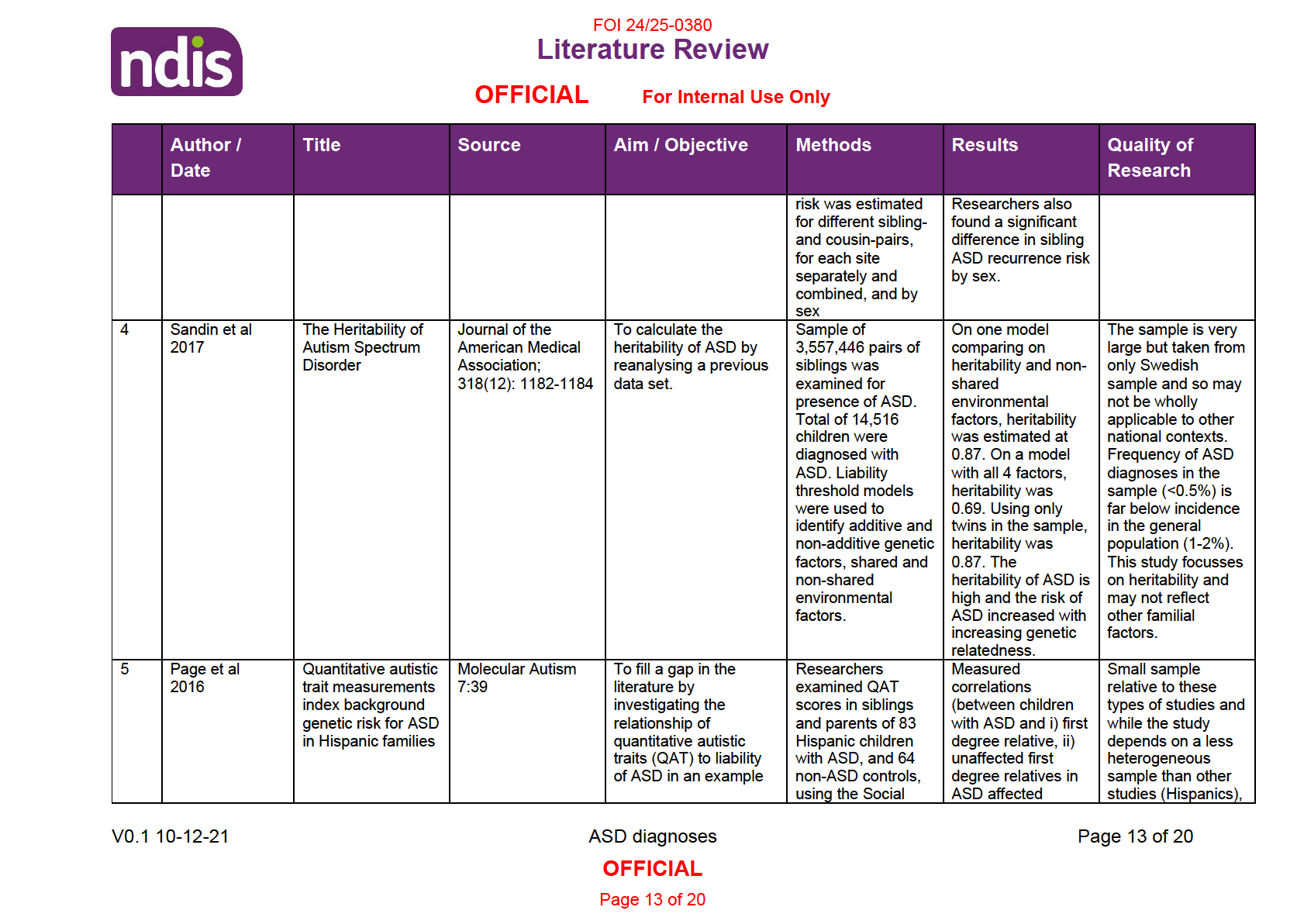

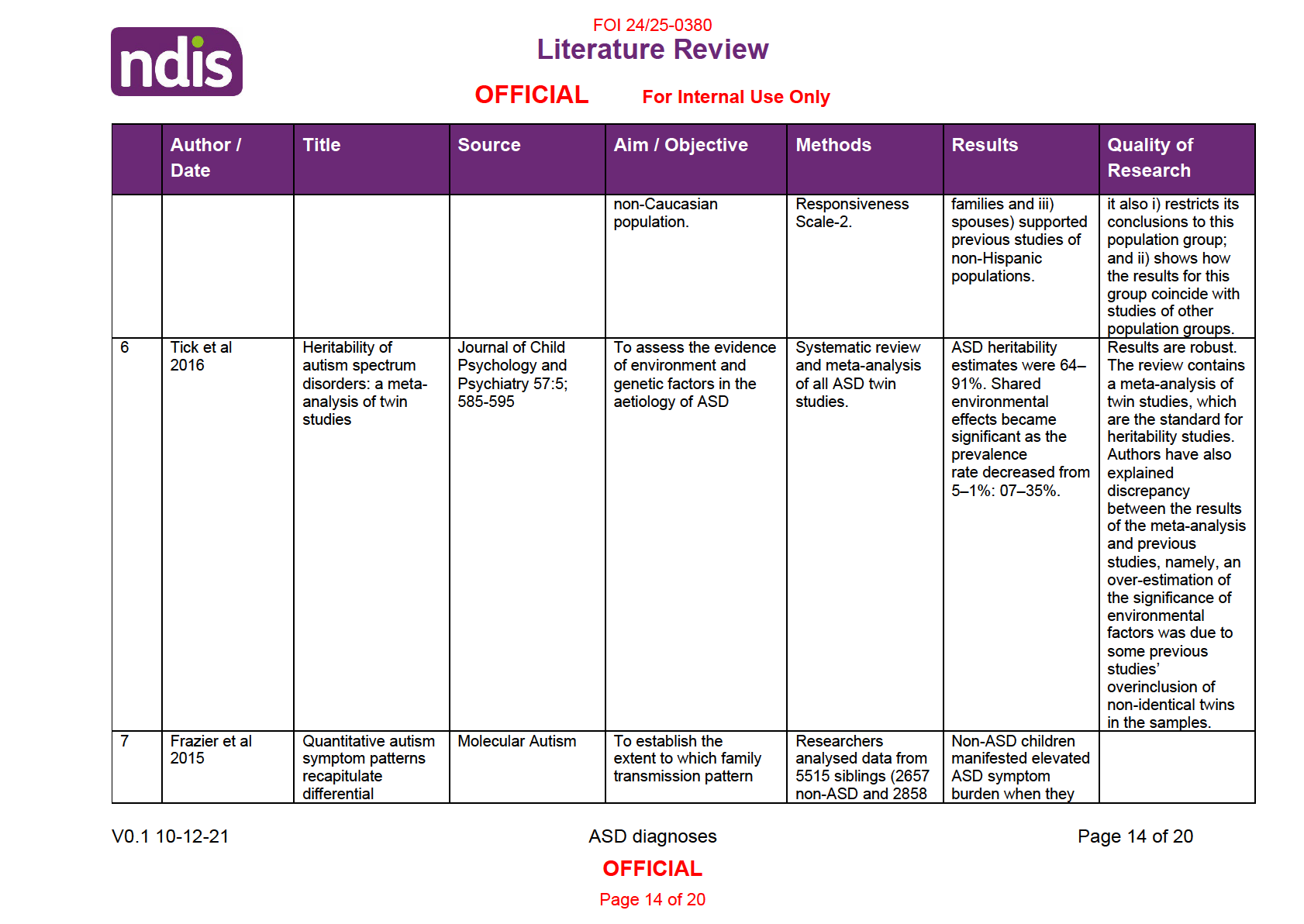

Estimations of heritability of ASD range from 0.64 – 0.91, with some consensus emerging in

the range 0.80 – 0.87 (Bai et al 2020; Sandin et al 2017; Tick et al 2016). High heritability

means that for any two people, the more genes they share with each other, the more likely it is

that they will share the highly heritable trait (Downes & Matthews, 2020). The closer the

genetic relationship between a person with ASD and their relative, the more likely the relative

will also have ASD. The literature notes recurrence rates of 80% for identical twins and 20%

for non-identical siblings (Bai et al 2020; Girault et al 2020).

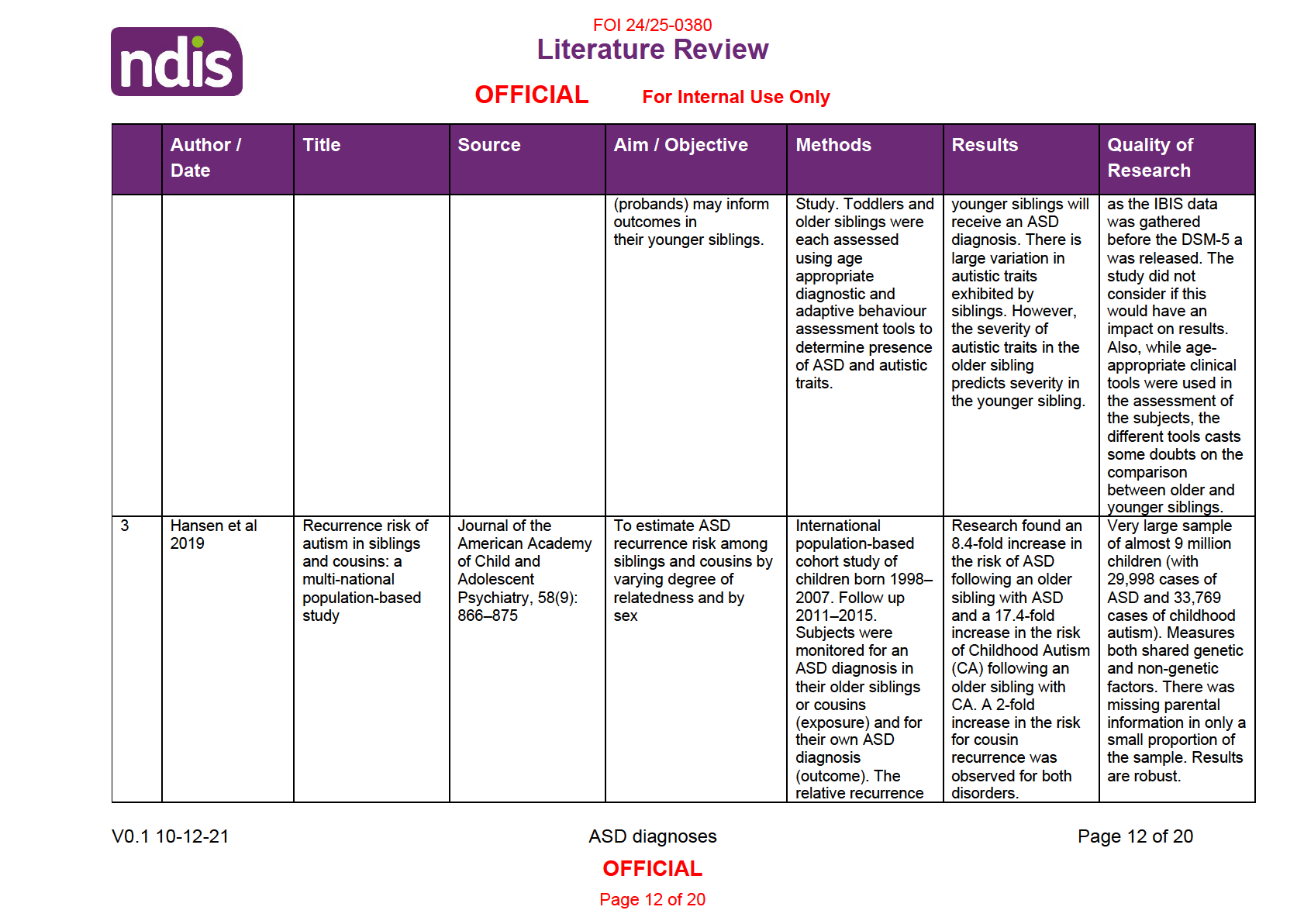

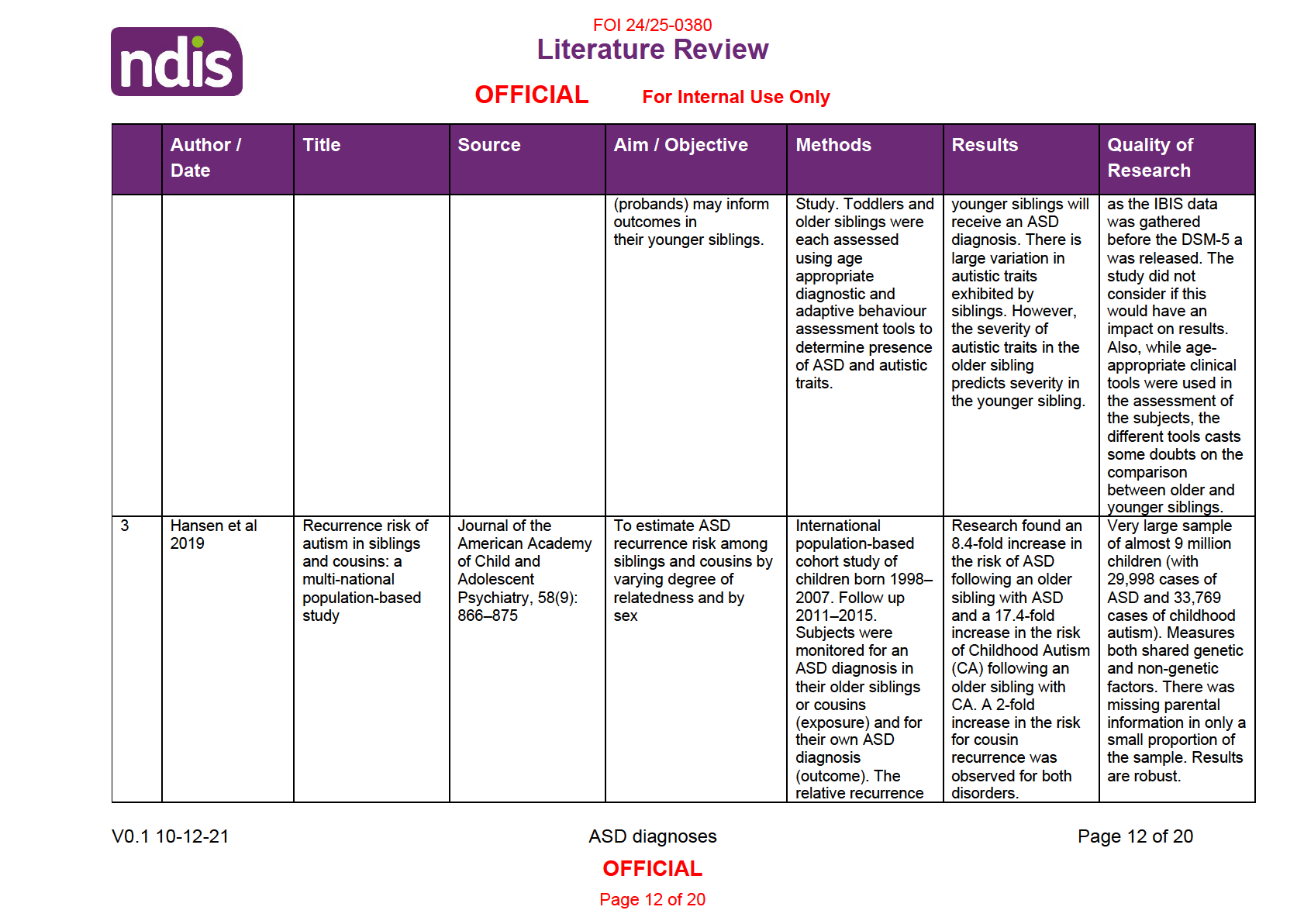

This is supported by population-based studies showing the likelihood of a person having ASD

is increased if they have a family member with ASD (Girault et al 2020; Bai et al, 2020;

Hansen et al 2019). One study predicts a 2-fold increase in likelihood of ASD diagnosis if you

have a cousin with ASD and an 8-fold increase in likelihood of ASD diagnosis if you have an

V0.1 10-12-21

ASD diagnoses

Page 2 of 20

OFFICIAL

Page 2 of 20

FOI 24/25-0380

Literature Review

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

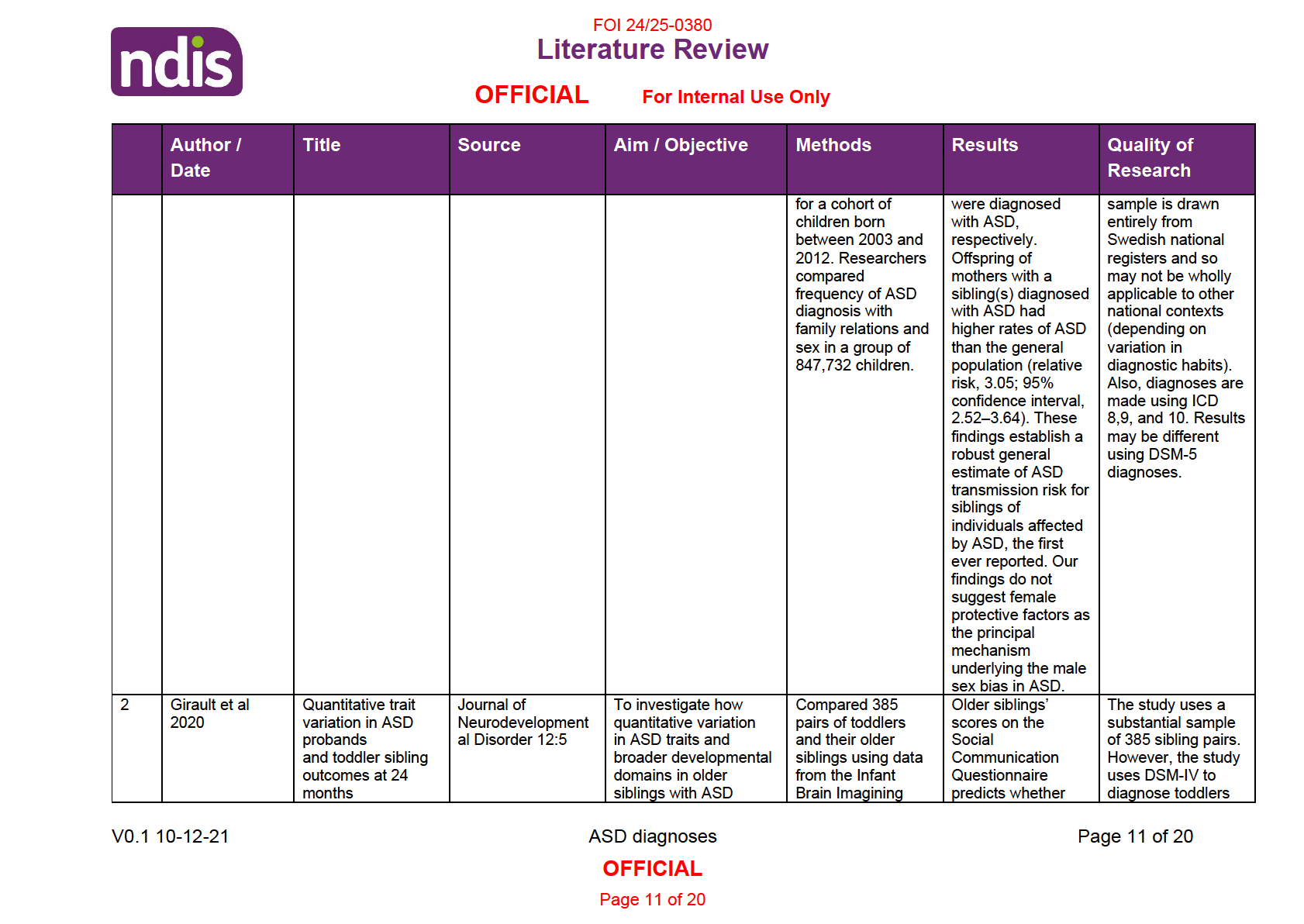

older sibling with ASD (Hansen et al 2019). Girault et al (2020) also note that a sibling is even

more likely to get a diagnosis of ASD if there are multiple people in the family with ASD.

Family members are also more likely to have more autistic traits (short of an ASD diagnosis) if

someone in the family is diagnosed with ASD (Girault et al 2020; Page et al 2016). Girault et al

also notes that a person with ASD getting a higher score on the Social Communication

Questionnaire results in an increased chance of their sibling getting a diagnosis of ASD

(Girault et al 2020).

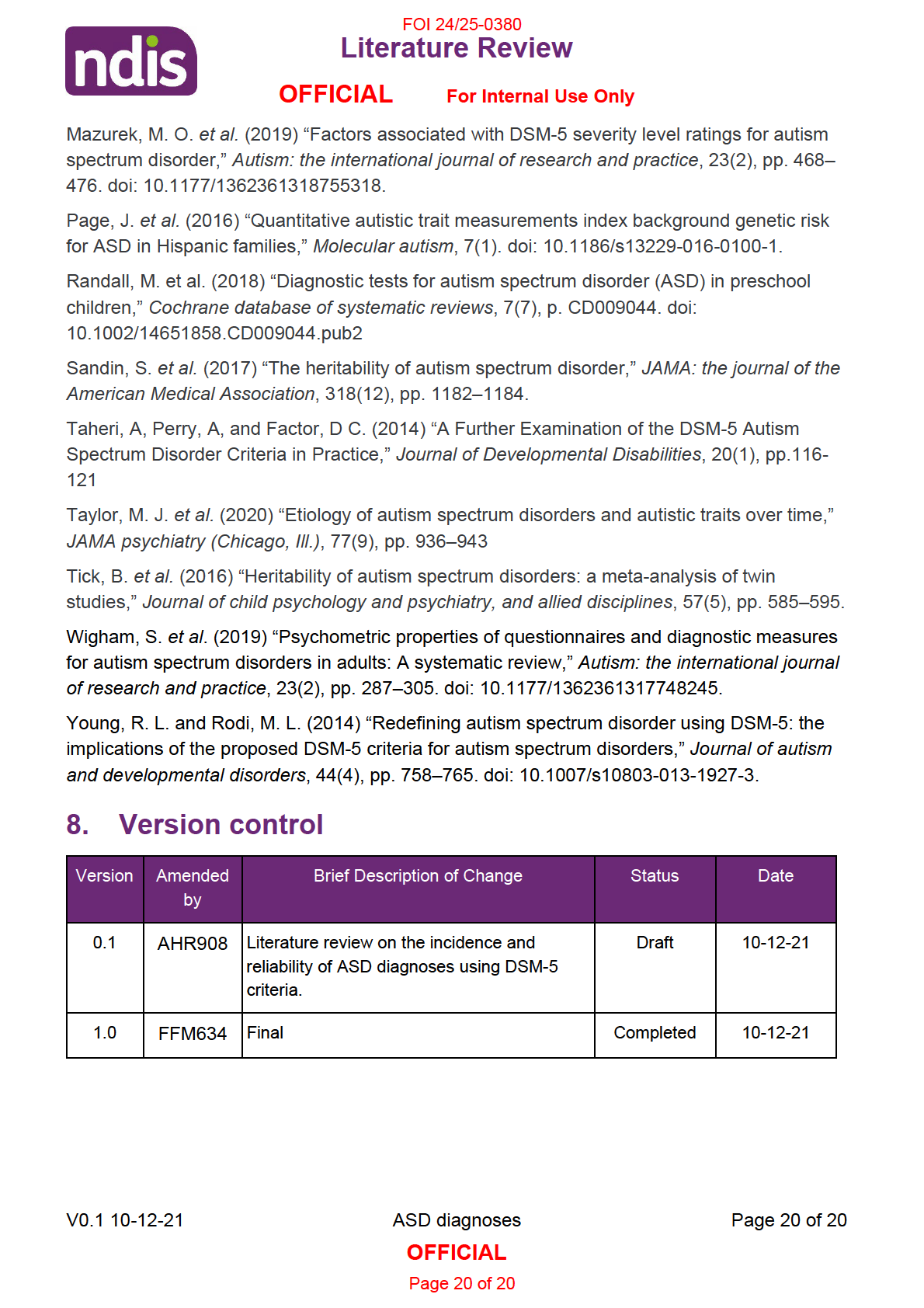

4. Accuracy and inter-rater reliability of ASD diagnoses

using DSM-5

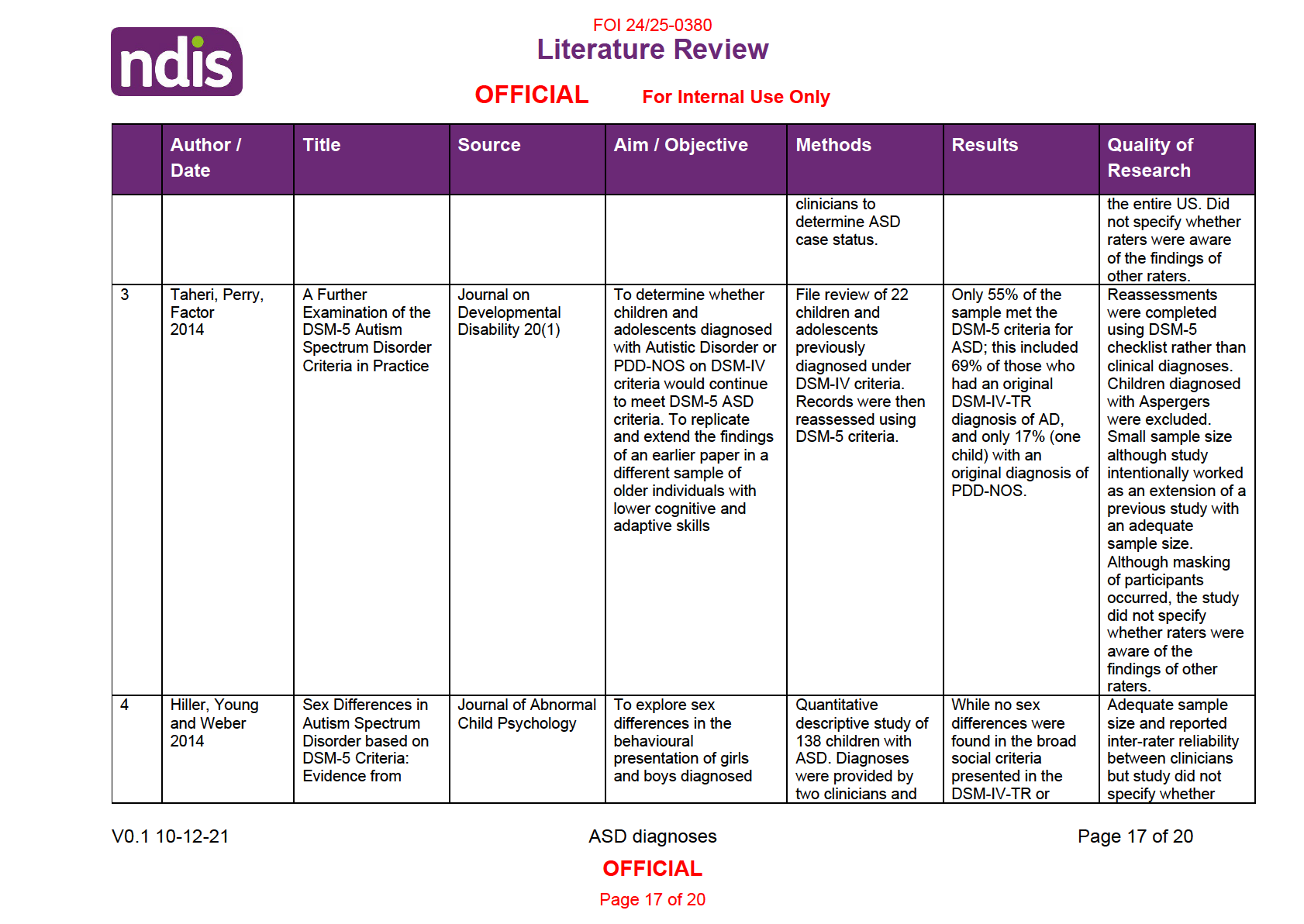

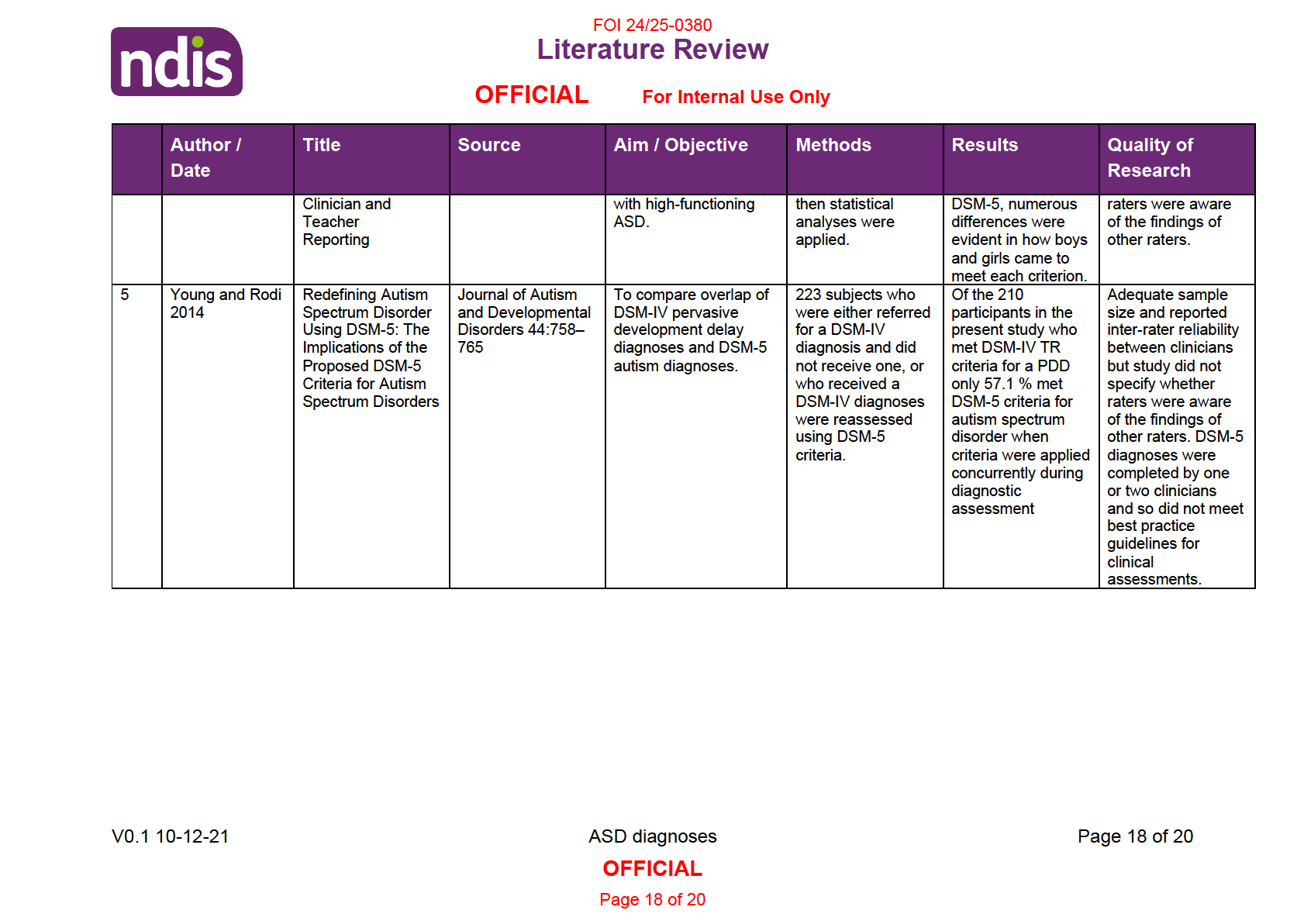

While I was able to locate information establishing inter-rater reliability of DSM-5 ASD

diagnoses, this should be treated with caution. The results do not come from studies that

explicitly set out to study the accuracy of DSM-5 diagnoses. Studies examining other features

of ASD or ASD diagnostic practices will often use inter-rater reliability to ensure study quality.

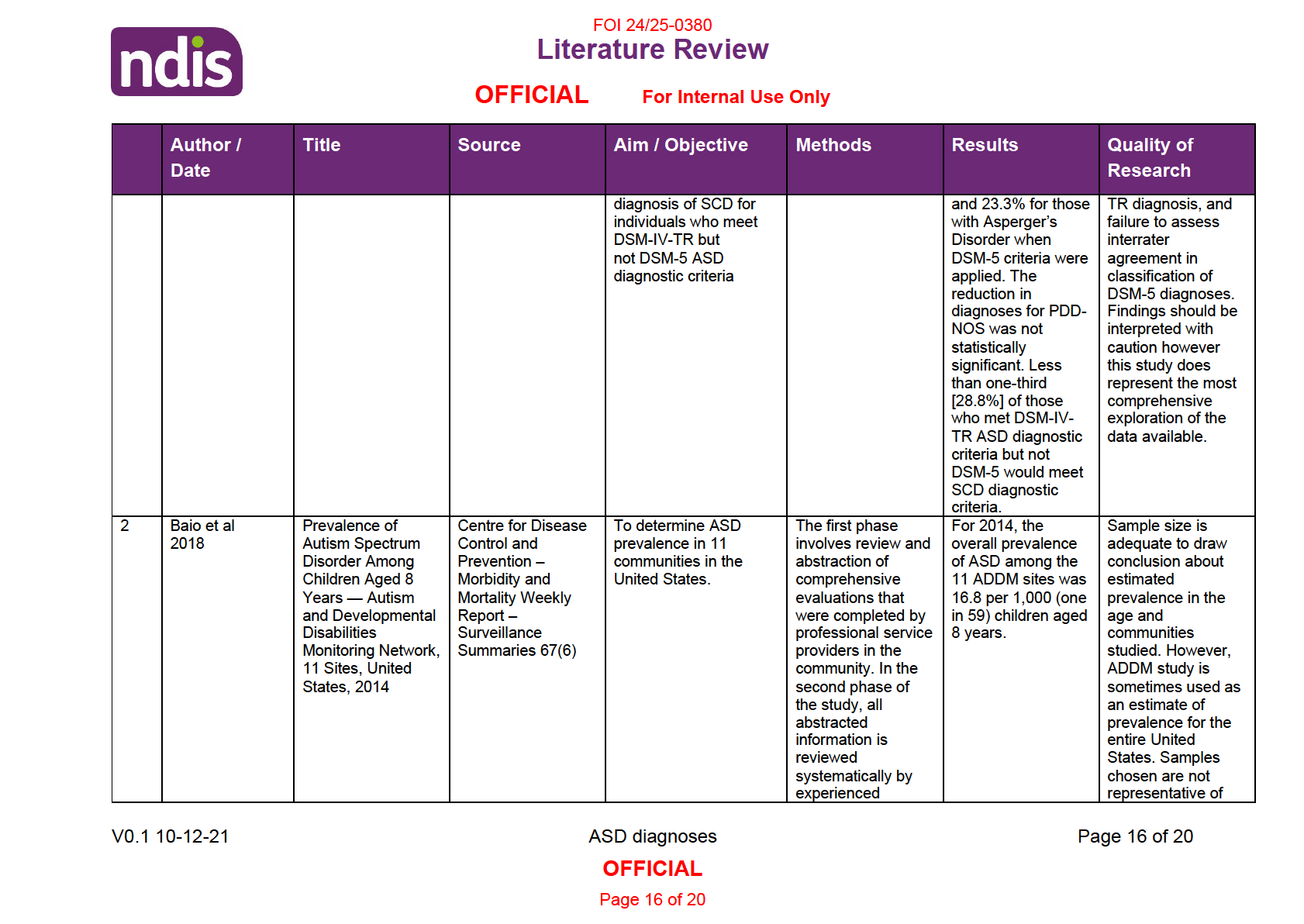

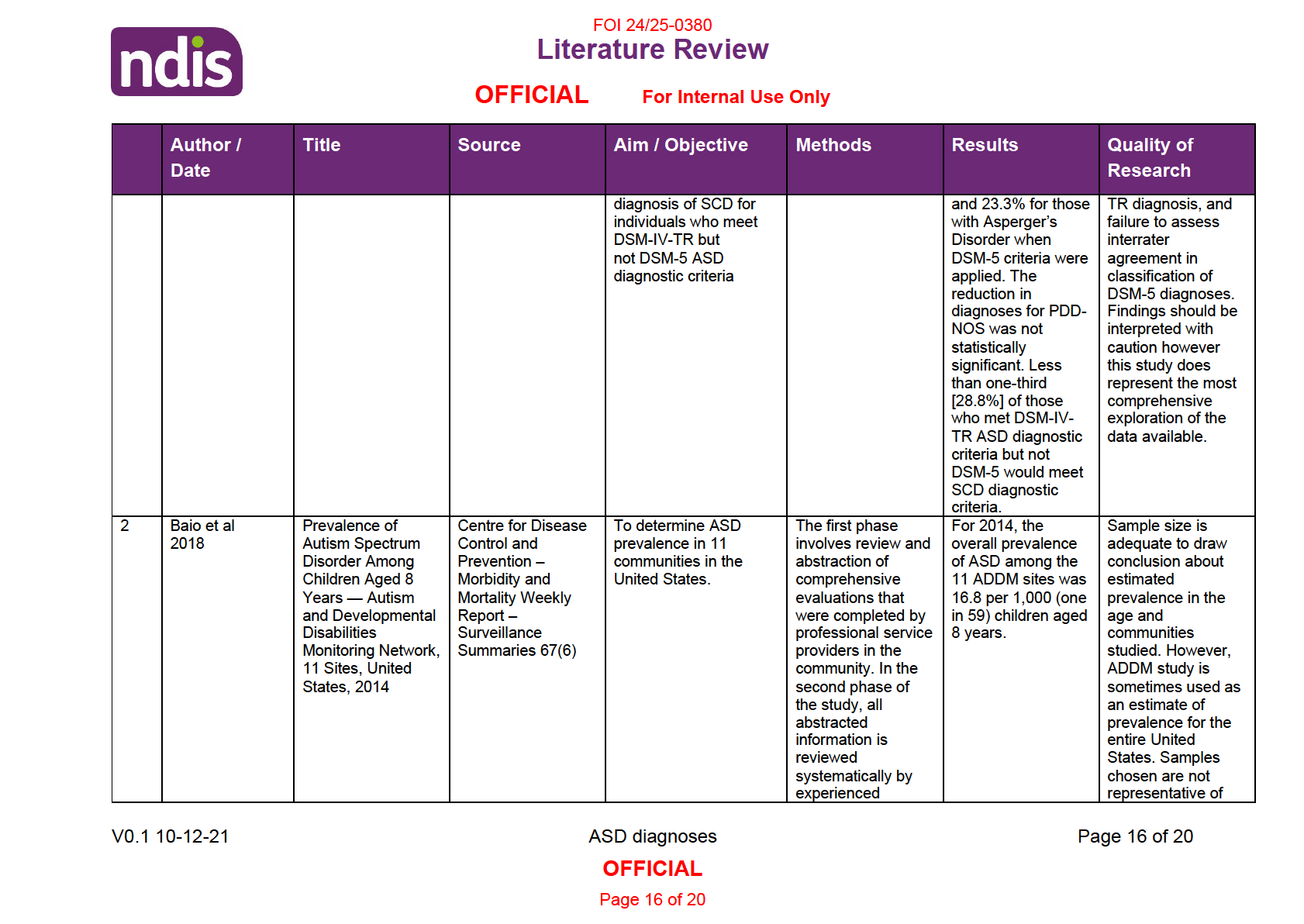

In their study of ASD prevalence, Baio et al found 92.3% inter-rater agreement on presence or

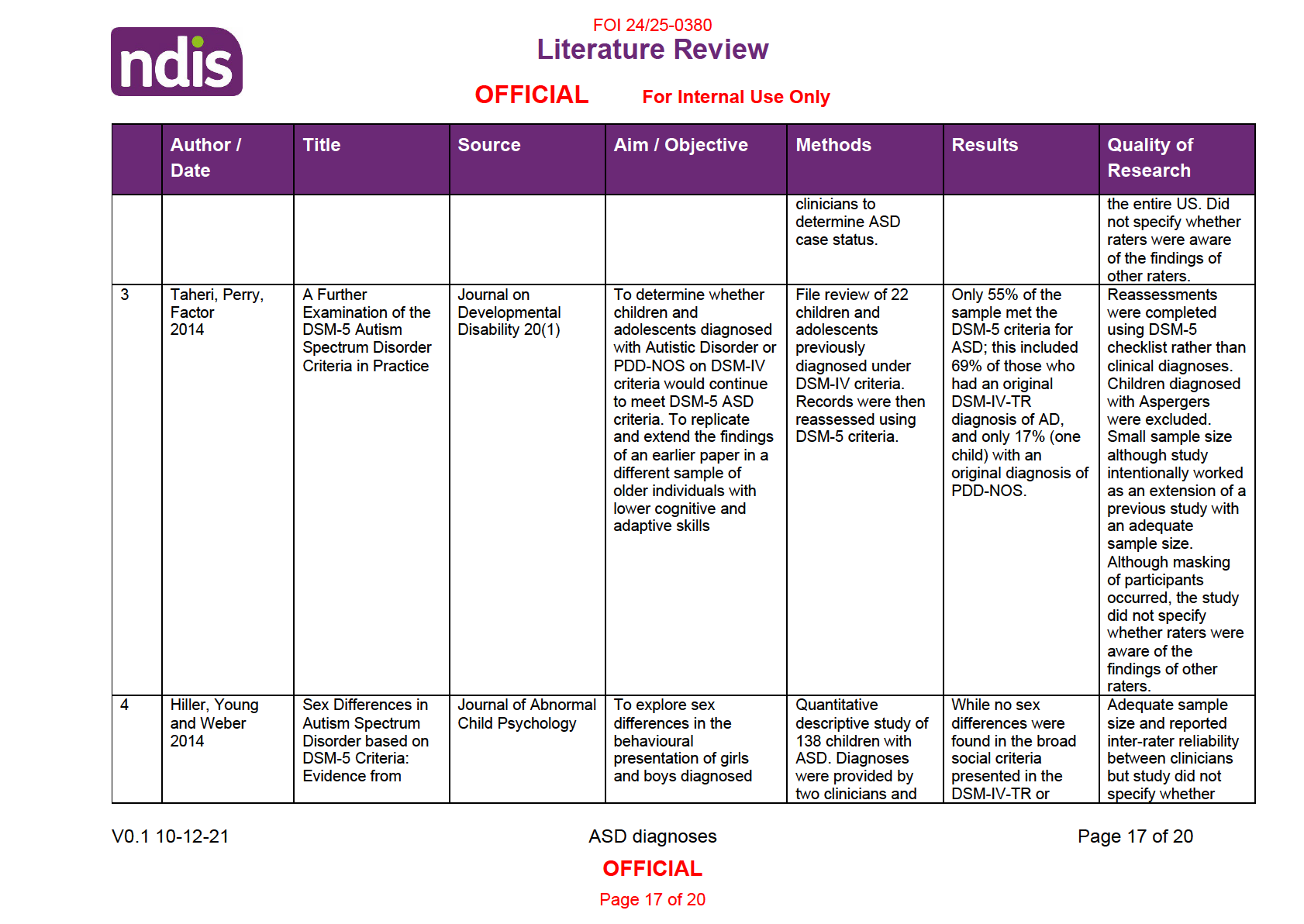

absence of ASD using DSM-5 criteria (2018, p.7). Taheri et al secured 100% inter-rater

agreement for overall diagnosis and between 70% and 100% agreement on individual criteria

(2014, p.118). In their study of gender differences in ASD diagnosis, Hiller, Young and Weber

found substantial inter-rater agreement with Cohen’s kappa scores of between 0.75 and 0.93

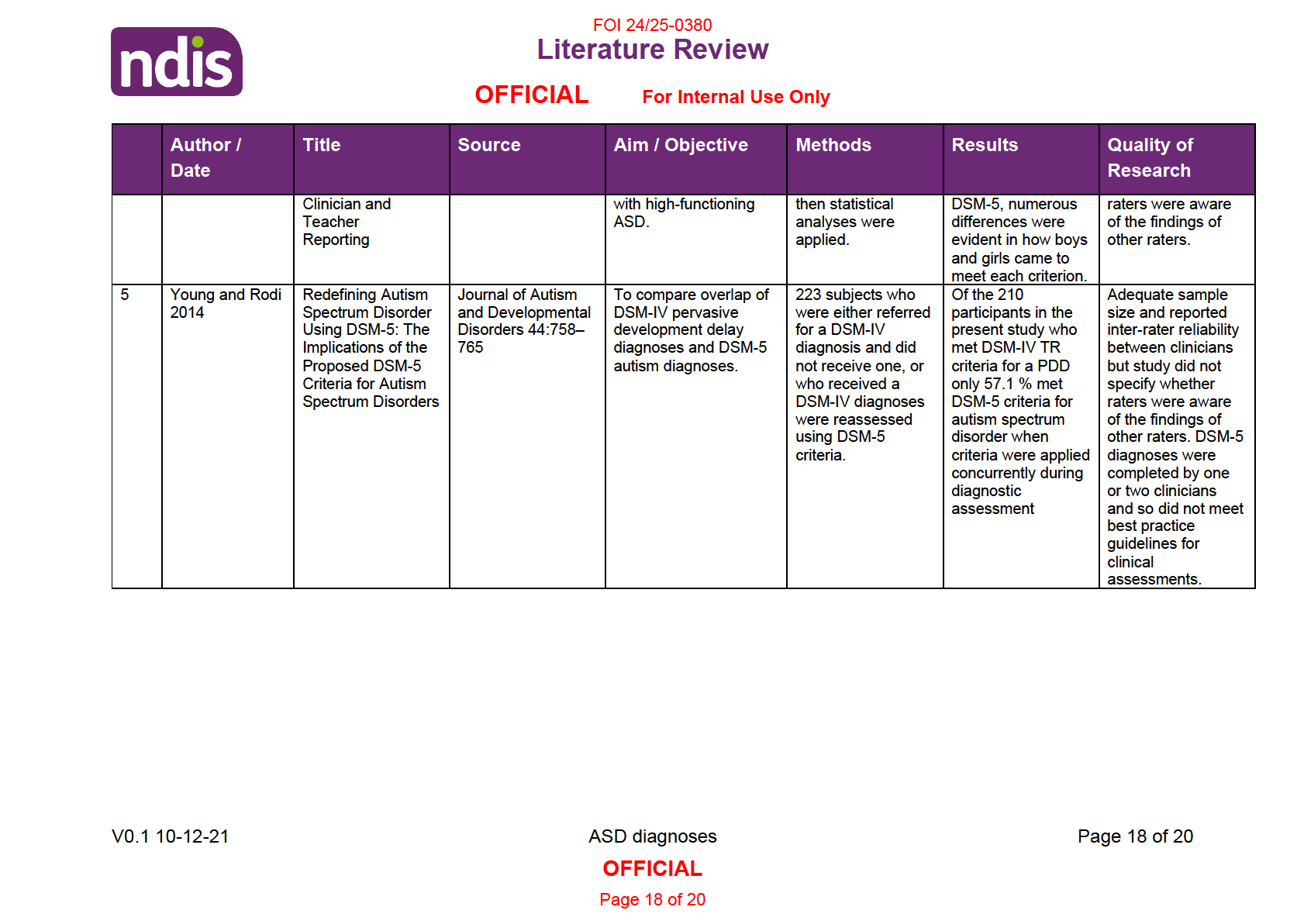

(2014, pp.4-5). Young and Rodi also secured strong inter-rater agreement for overall diagnosis

with Cohen’s kappa score of 0.91 (2014, p.761). These results demonstrate potential for high

inter-rater agreement with DSM-5 ASD diagnoses, with somewhat lower agreement in

individual criteria. They do not speak to accuracy of severity ratings (i.e. requiring support,

requiring substantial support, requiring very substantial support).

Mazurek et al (2019) looked at use of severity ratings among clinicians. They found that

assessment of severity levels of social communication and restrictive, repetitive behaviours

using DSM-5 criteria largely agrees with other assessment tools as well as parental

assessment of severity (p.7). However, they do point out a strong link between intelligence and

severity ratings, which may mean that clinicians are conflating ASD symptoms with difficulties

related to intellectual disability. Mazurek et al suggest that clinicians may be having difficulty:

“determining whether to assign ratings based on ASD symptom severity alone (more

consistent with text examples) or based largely on need for support (more consistent

with the level descriptors). If clinicians adhere to the latter interpretation, there may be

greater potential for conflation of intellectual and symptom-related impairment. This

poses problems for both inter-rater reliability and construct validity” (p.7).

Mazurek et al are also unaware of any studies looking at the inter-rater reliability of severity

level assessments (p.8).

V0.1 10-12-21

ASD diagnoses

Page 3 of 20

OFFICIAL

Page 3 of 20

FOI 24/25-0380

Literature Review

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

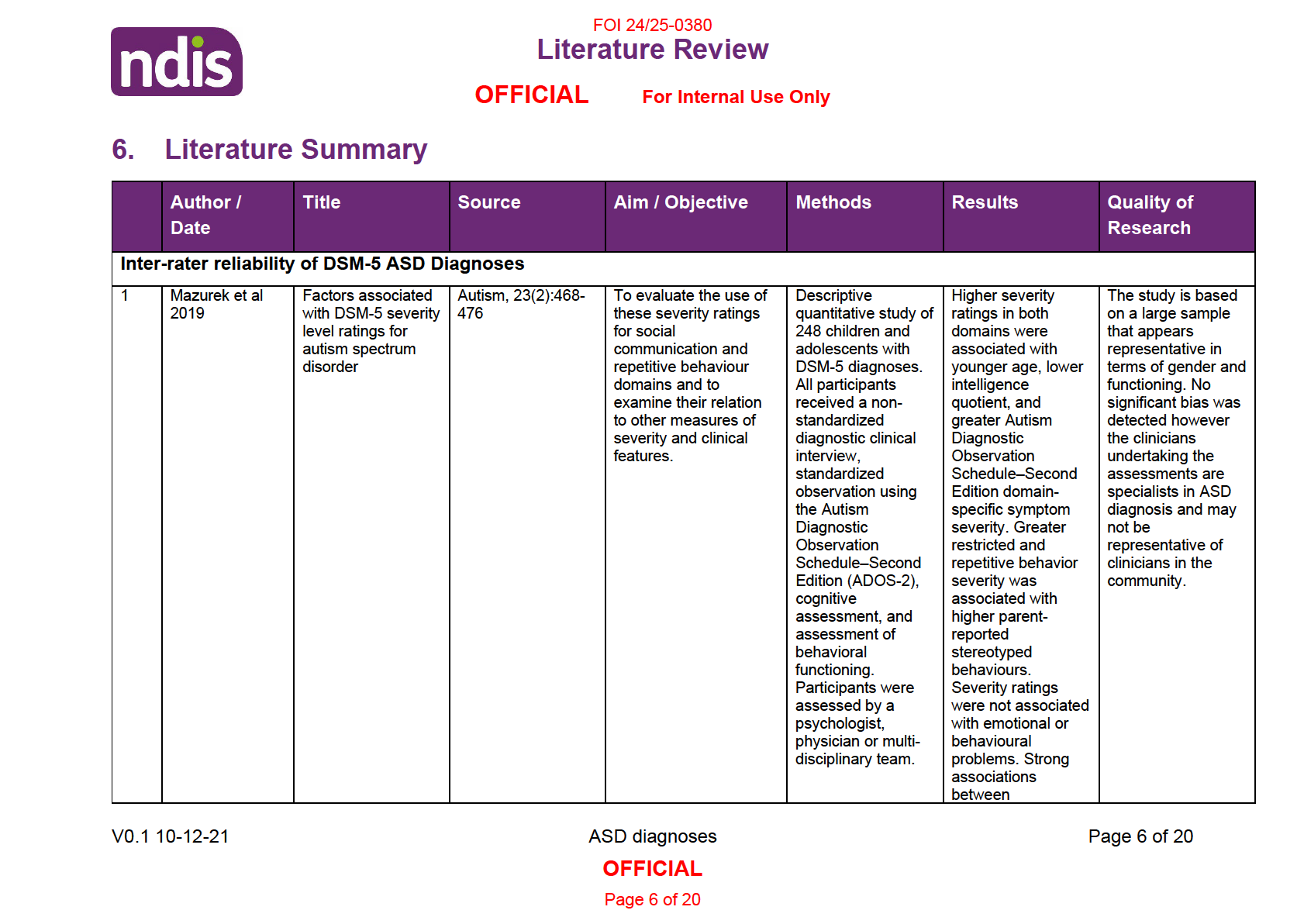

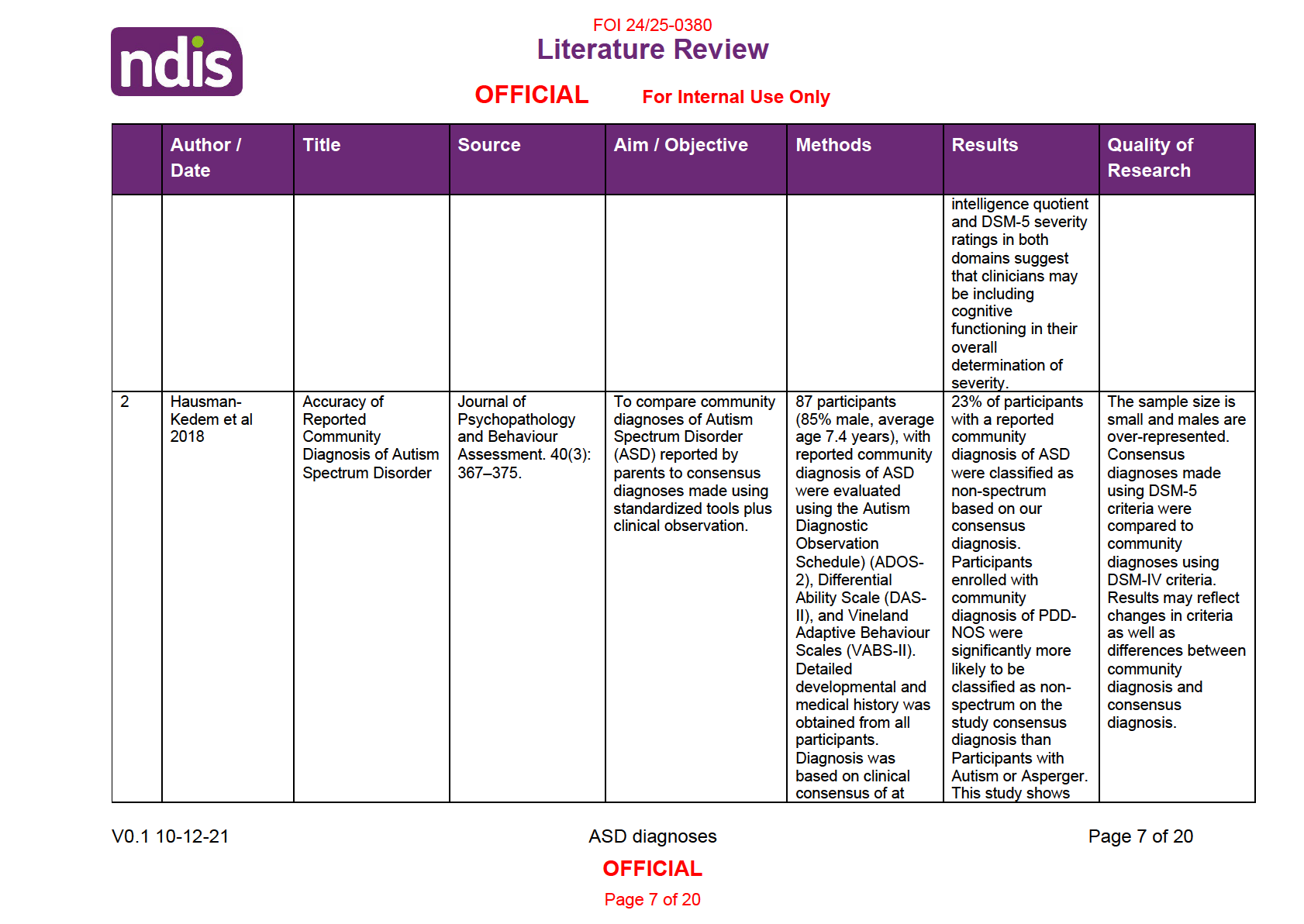

Hausman-Kedem et al looked at a group of 87 participants who had been diagnosed with ASD

from psychologists or physicians in the community. They had predominately single-disciplinary

diagnoses. Hausman-Kedem et al found the diagnoses did not hold up in 23% of cases when

compared with best practice clinical estimates (2018, p.6). They also find that results of Autism

Diagnostic Observation Schedule-2 (ADOS-2) substantially agrees with final best practice

clinical estimates (2018, p.7). While the support for ADOS-2 is backed up by other studies, the

discrepancy between community diagnoses and best practice clinical estimates is complicated

by the participants’ having DSM-IV diagnoses and the researchers using updated DSM-5

categories.

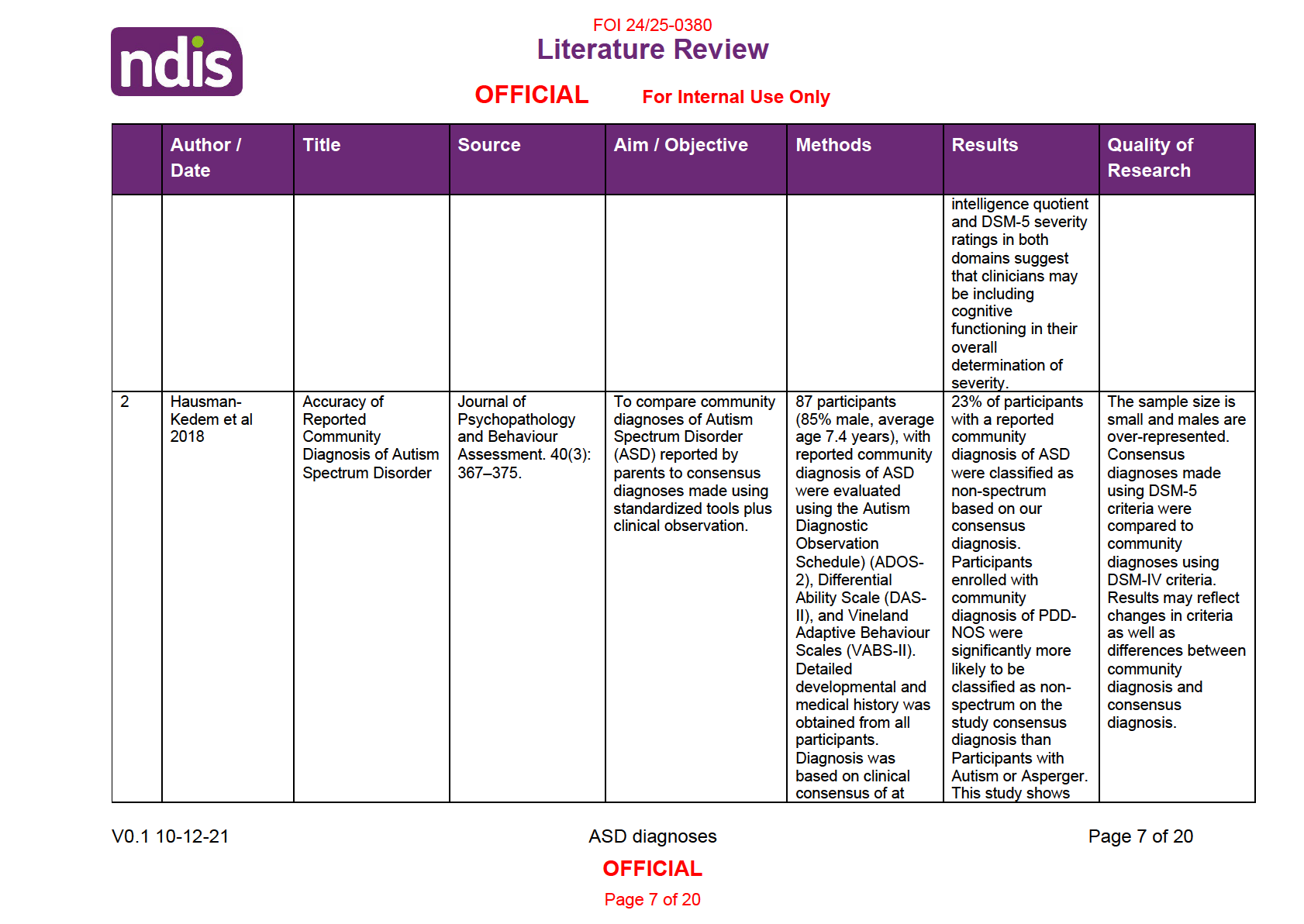

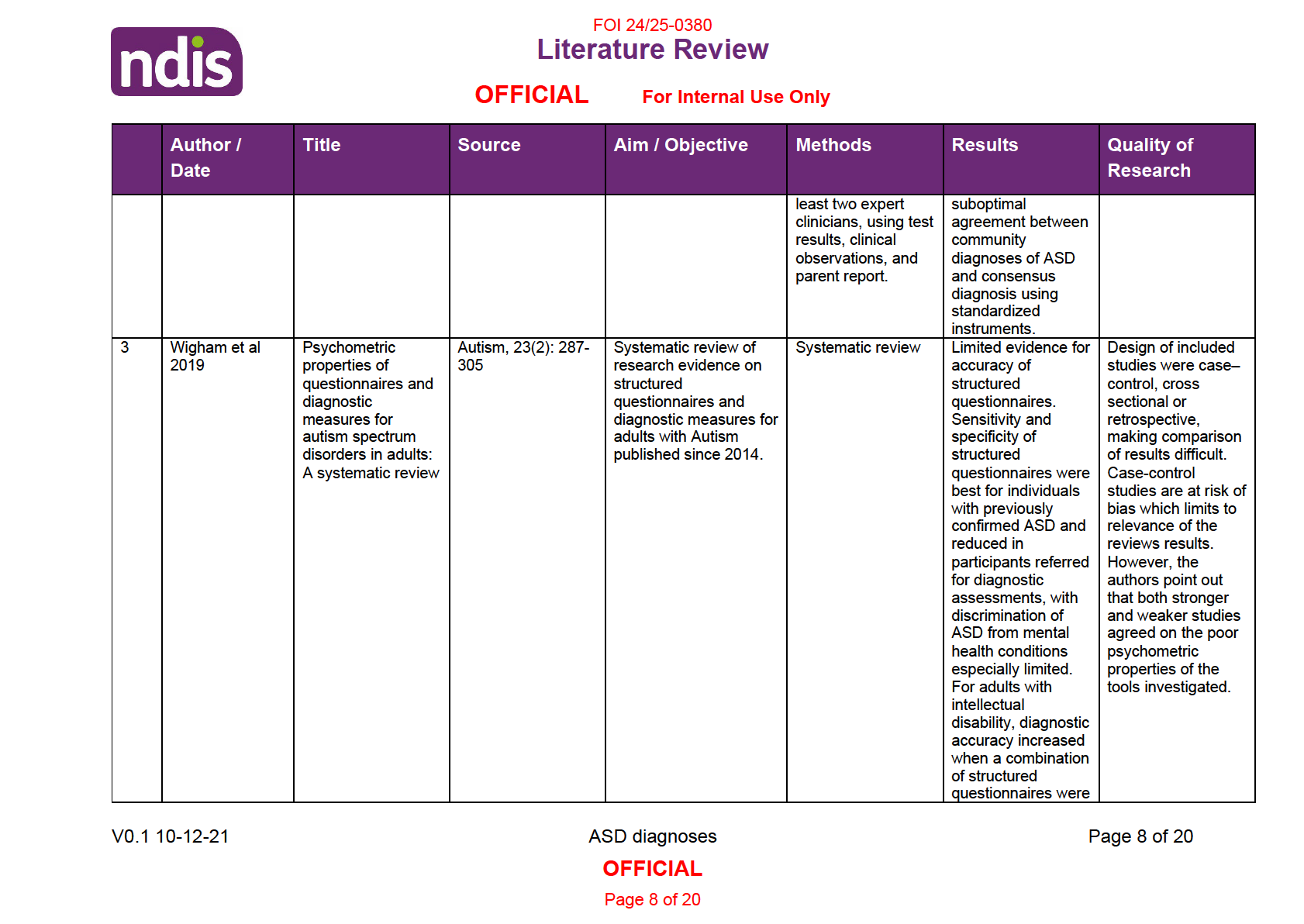

In their 2018 systematic review, Wigham et al found some support for diagnostic measures

such as ADOS for adults, though they note that accuracy increases when multiple

questionnaires and measures are used. They also observe that difficulties arise when

distinguishing between ASD and some mental health conditions such as schizophrenia (p.15).

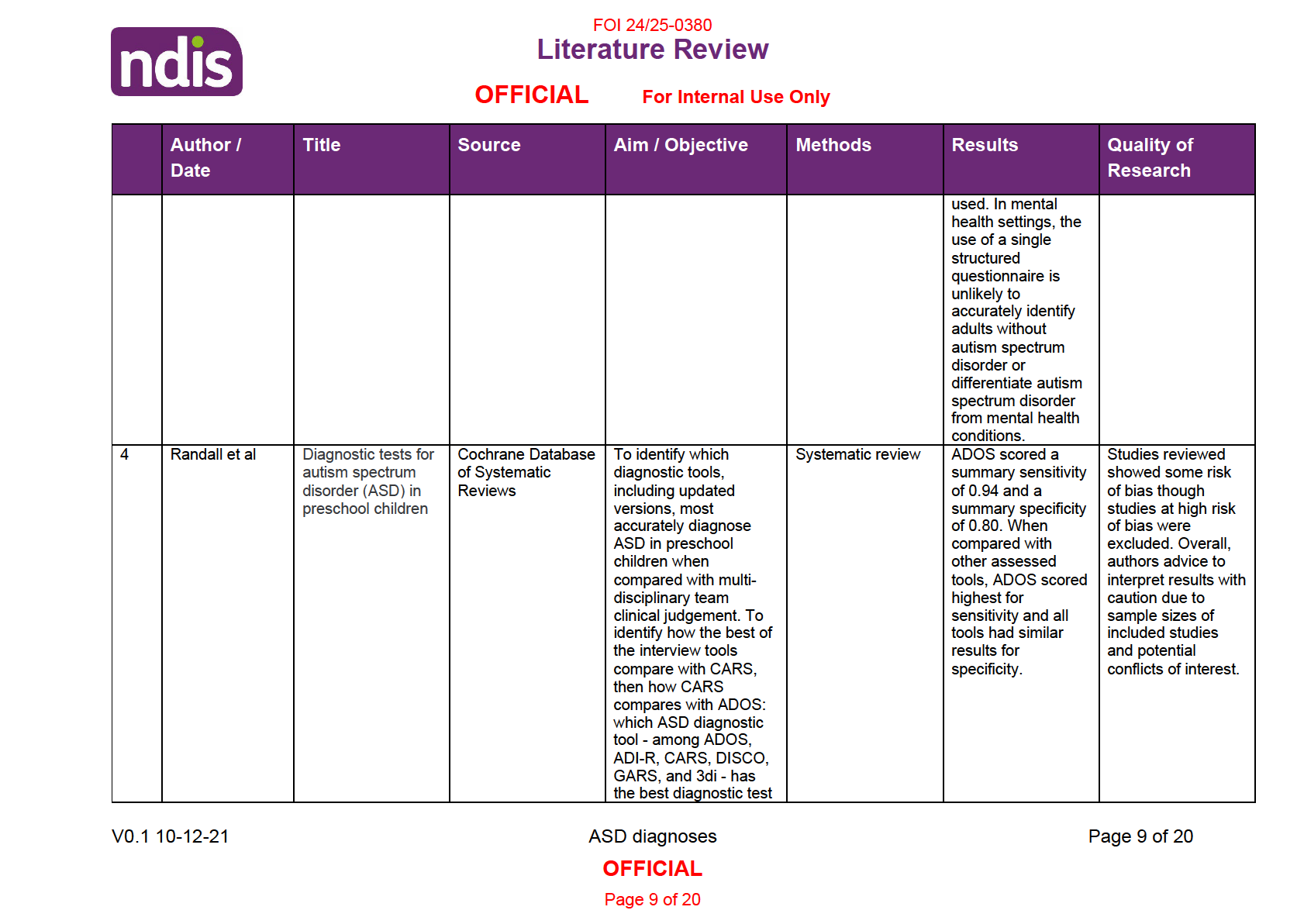

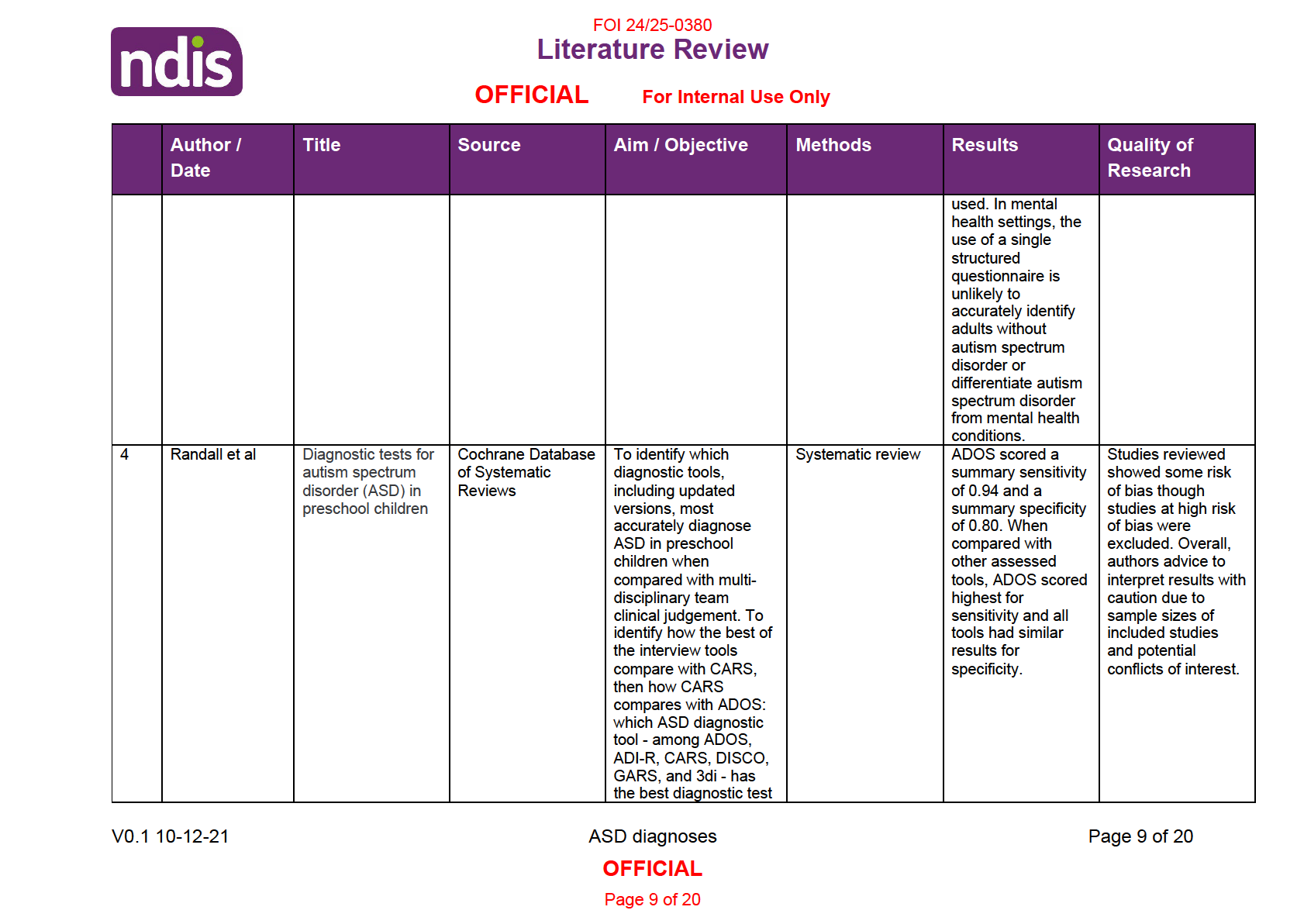

While there is better evidence to support tools used to diagnose ASD in children (Whigham,

2018, p.1), Randall et al found reason to be cautious about results supporting accuracy of

diagnostic tools (2018, p.3). According to the evidence obtainable, ADOS scored highest for

sensitivity and all tools assessed had similar results for specificity (p.2).

Further investigation will be required to provide a fuller picture of the overall accuracy of DSM-

5 diagnoses and of tools based on DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. Despite some lack of confidence

in the evidence, there is agreement in the literature that use of a variety of tools from a multi-

disciplinary team gives the highest chance of correctly diagnosing a person with ASD.

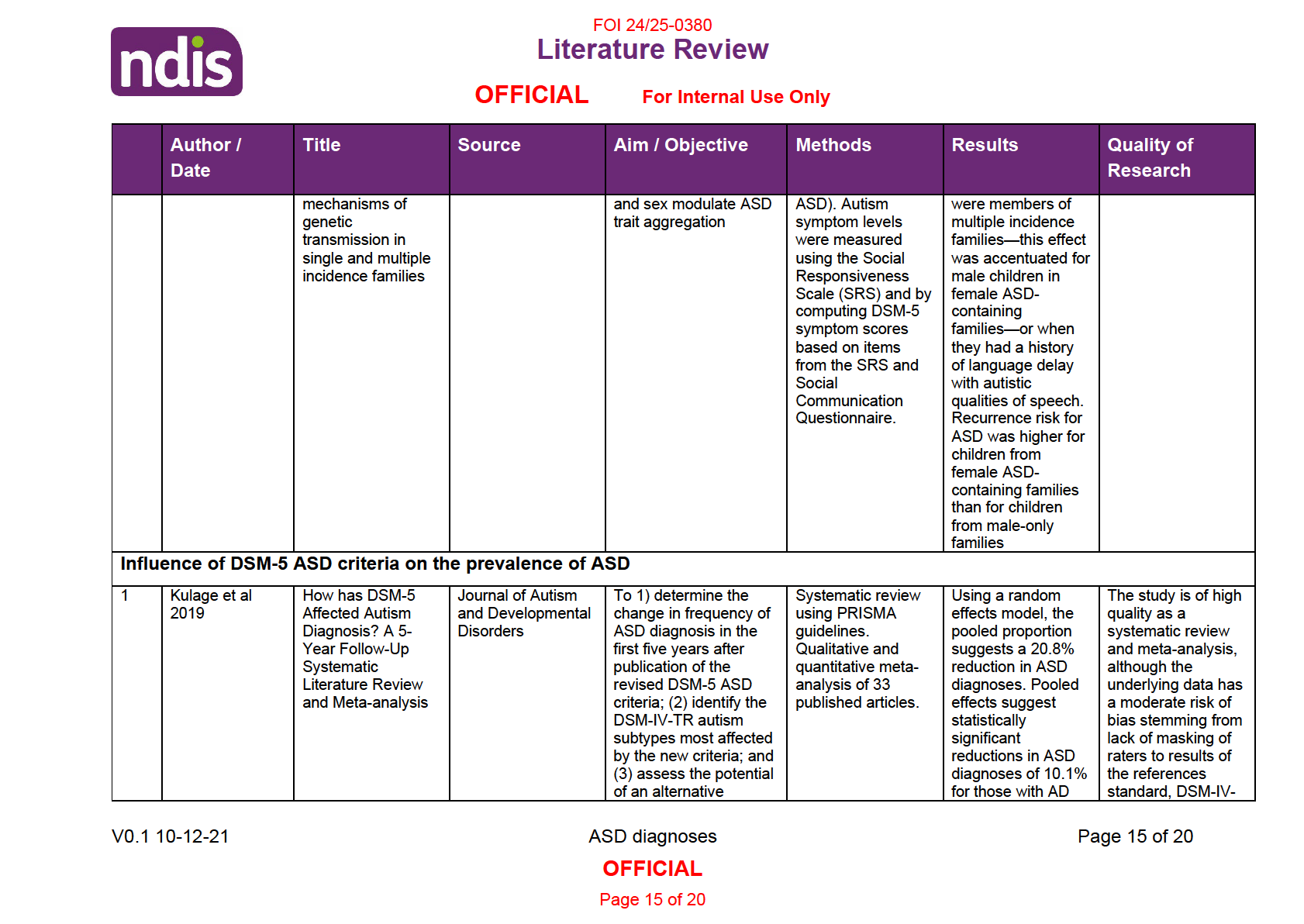

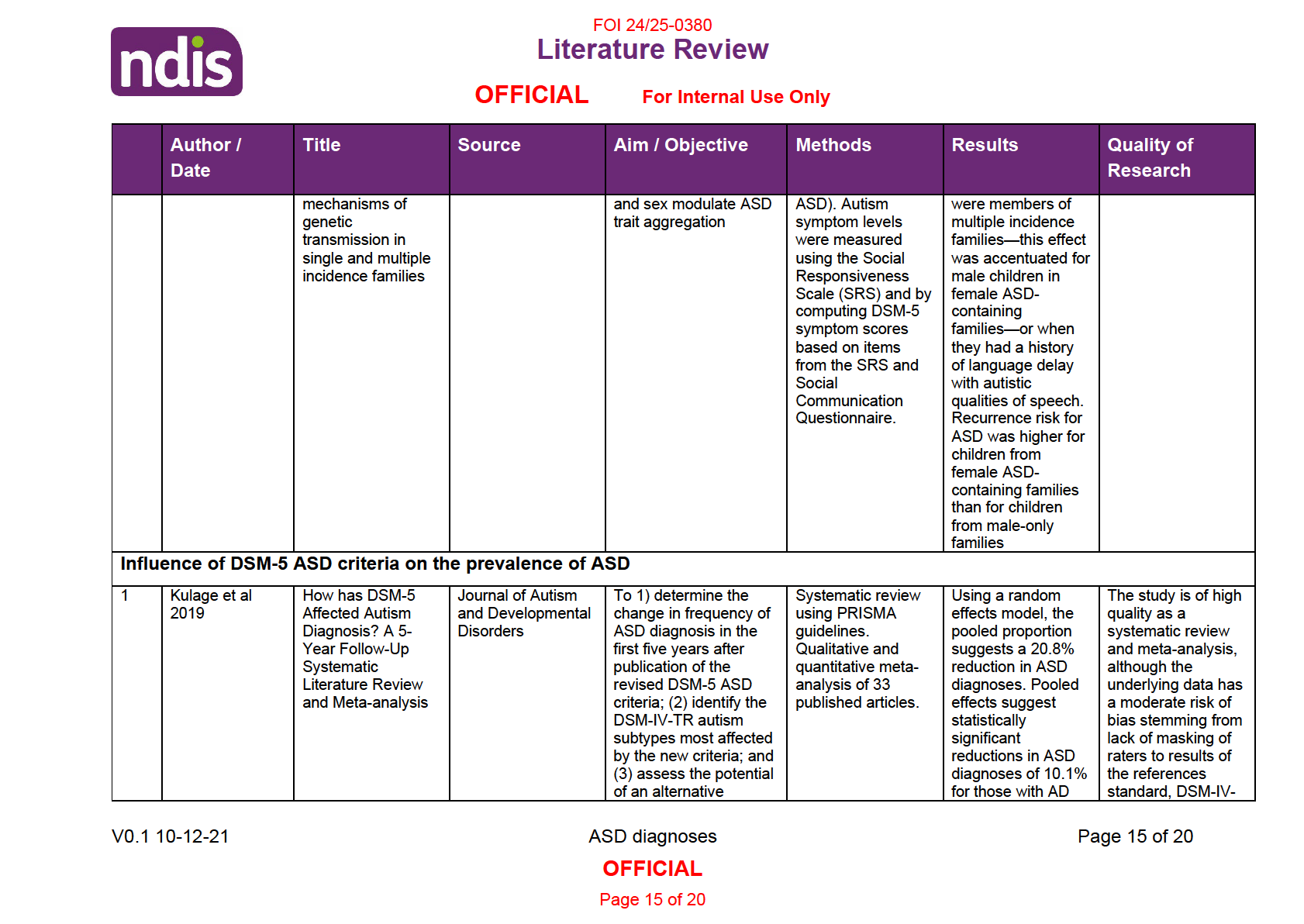

5. Influence of DSM-5 ASD criteria on the prevalence of

ASD

Autism prevalence rates are increasing (Taylor et al, 2020; Chiarotti & Venerossi, 2020; CDC

2020). The Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring network (ADDM) estimates

prevalence at 1 in 44 in sample United States communities (CDC 2020; Maener et al, 2021;

Baio et al, 2018). Autism Spectrum Australia estimates prevalence at 1 in 70 in Australia

(Autism Spectrum Australia, 2018). The reasons for the increase are likely to be complex and

the exact proportion of the increase that is attributable to different factors is still a matter for

debate. Kulage et al suggest:

“parental awareness and acceptance, less stigmatization, better trained clinicians, more

thorough data collection methods, and even increasing genetic tendencies could be

contributing factors. In addition, comorbid diagnoses are now allowable for ASD under

DSM-5, enabling clinicians to give multiple comorbid diagnoses of intellectual disability,

ASD, and ADHD, which could also explain why ASD rates have continued to rise since

publication of the DSM-5” (Kulage et al, 2019, p.19).

V0.1 10-12-21

ASD diagnoses

Page 4 of 20

OFFICIAL

Page 4 of 20

FOI 24/25-0380

Literature Review

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

Estimates of ASD prevalence are rising despite tightening diagnostic criteria in the current

addition of the DSM-5. Since before publication of the DSM-5 there was concern about what

the changes to ASD diagnostic criteria would do to ASD prevalence rates and especially

whether people who failed to meet the new criteria would no longer be eligible for support

(Kulage et al, 2019).

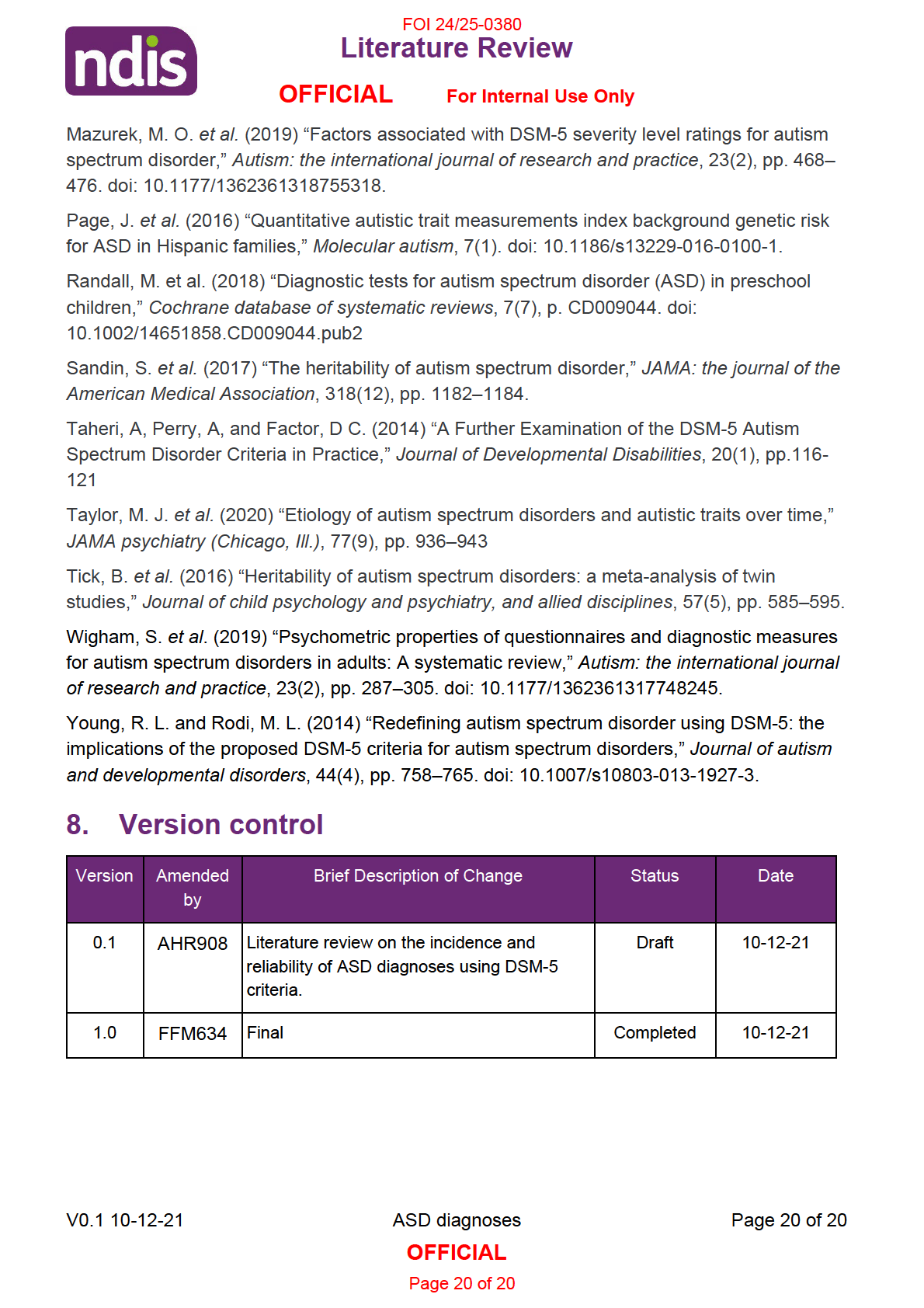

Kulage et al published a systematic review of the literature looking at the effect of the changes

to ASD diagnostic criteria between the DSM-IV-TR and the DSM-5. They found that

approximately 1 in 5 people who would have received a diagnosis in DSM-IV-TR would not

have received a diagnosis in the DSM-V. Further, only 28.8 percent of those who no longer

meet ASD criteria would go on to meet diagnostic criteria for Social Communication Disorder

(SCD) (Kulage et al, 2019, p.19). This means roughly 14% of people who met diagnostic

criteria under DSM-IV no longer meet criteria for ASD or SCD. It is unclear what proportion of

those people would go on to meet other diagnostic criteria and what proportion would remain

below threshold for any DSM-5 diagnosis.

According to this review, DSM-5 is contributing to a reduction in ASD diagnoses while the

overall prevalence estimates continue to rise.

V0.1 10-12-21

ASD diagnoses

Page 5 of 20

OFFICIAL

Page 5 of 20

FOI 24/25-0380

Literature Review

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

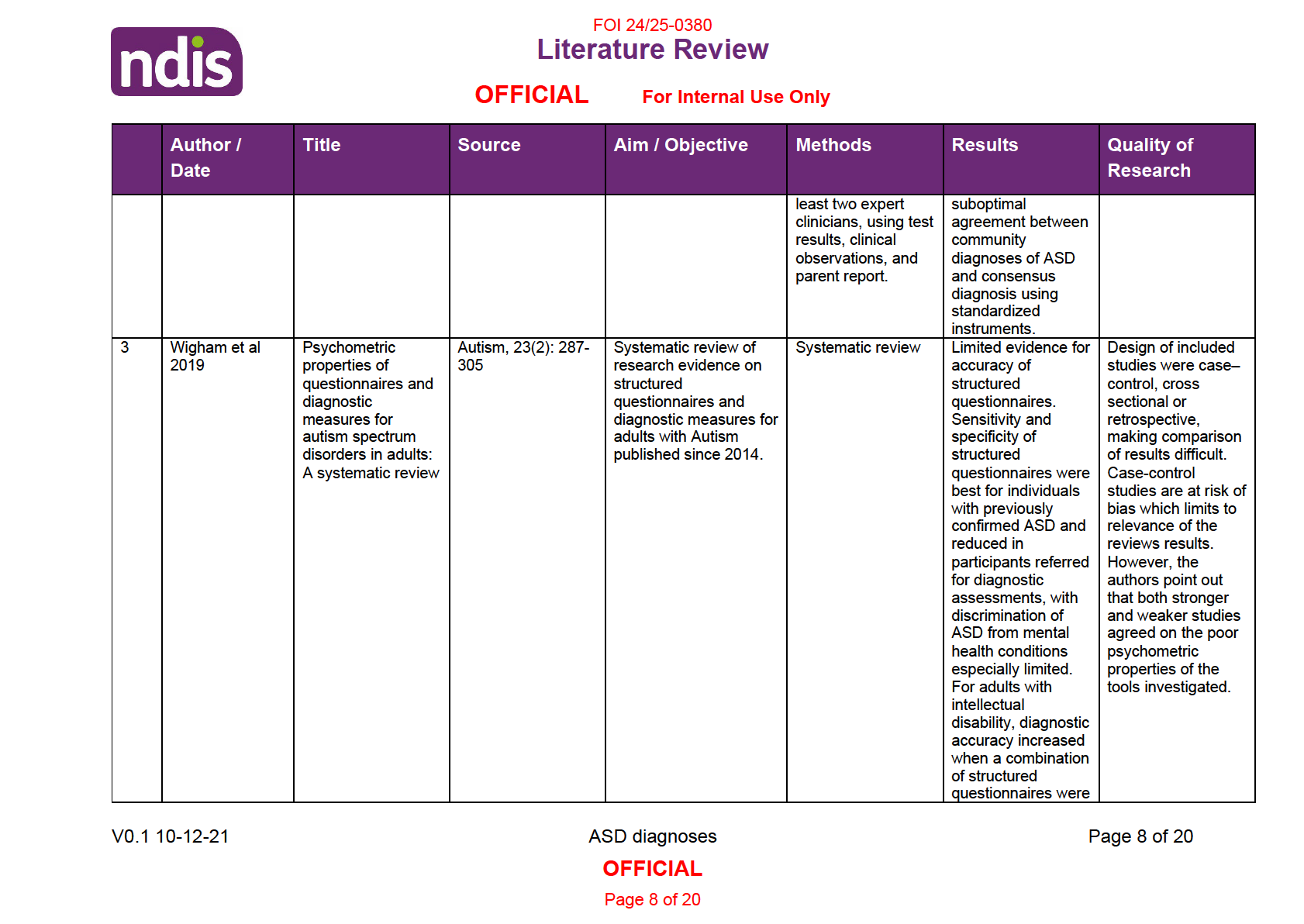

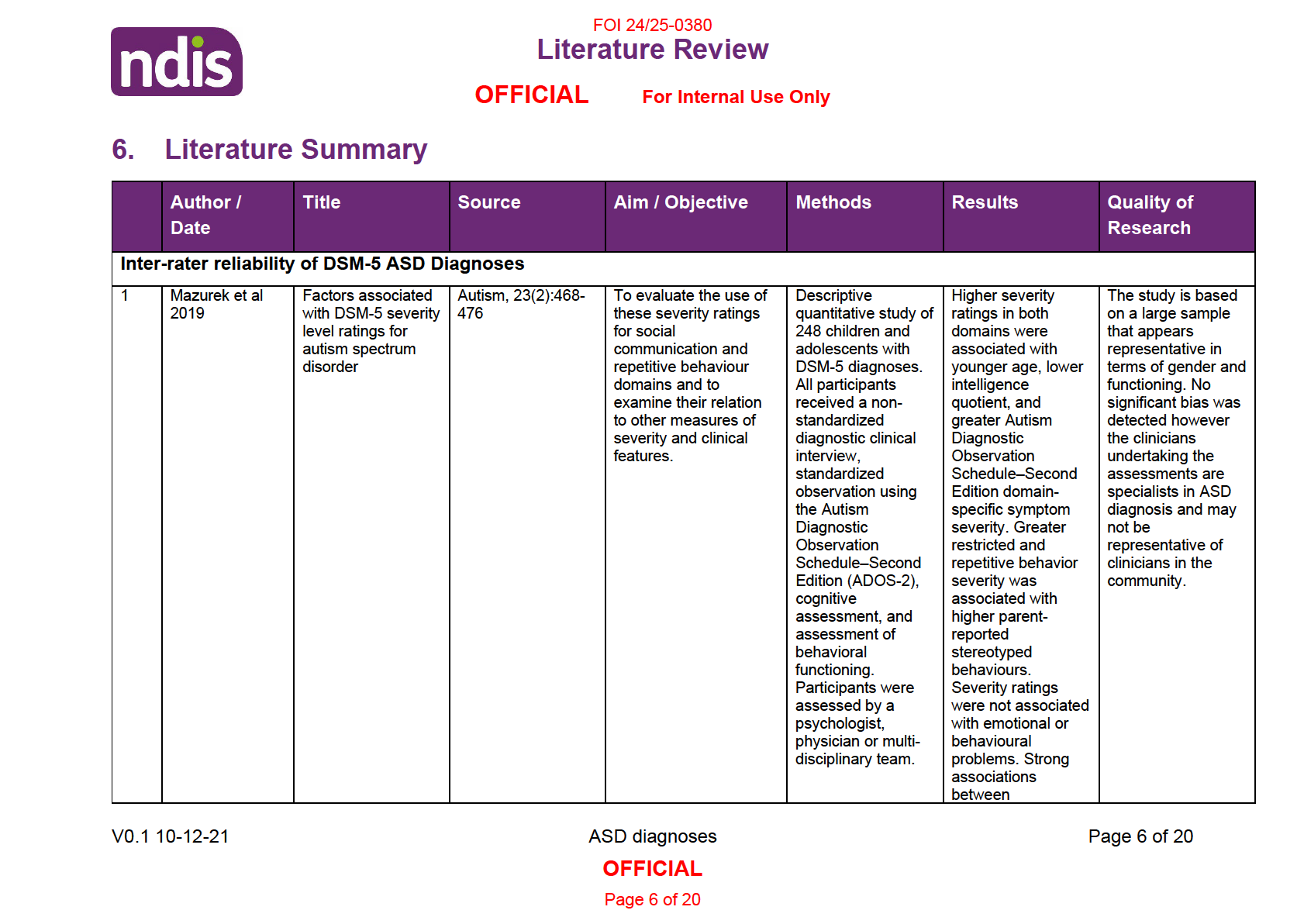

7. References

Autism Spectrum Australia (2018)

Autism prevalence rate up by an estimated 40% to 1 in 70

people. Autismspectrum.org.au. Available at: https://www.autismspectrum.org.au/news/autism-

prevalence-rate-up-by-an-estimated-40-to-1-in-70-people-11-07-2018 (Accessed: December

9, 2021).

Bai, D.

et al. (2020) “Inherited risk for autism through maternal and paternal lineage,”

Biological psychiatry, 88(6), pp. 480–487.

Baio, J.

et al. (2018) “Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years -

autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2014,”

MMWR Surveil ance Summaries, 67(6), pp. 1–23

Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (2020)

Autism prevalence studies data table,

Cdc.gov. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data/autism-data-table.html

(Accessed: December 9, 2021).

Chiarotti, F. and Venerosi, A. (2020) “Epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders: A review of

worldwide prevalence estimates since 2014,”

Brain sciences, 10(5)

Downes, S. M. and Matthews, L. (2020) “Heritability,”

The Stanford Encyclopedia of

Philosophy. Spring 2020. Edited by E. N. Zalta. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford

University.

Girault, J. B.

et al. (2020) “Quantitative trait variation in ASD probands and toddler sibling

outcomes at 24 months,”

Journal of neurodevelopmental disorders, 12(1), p. 5.

Hansen, S. N.

et al. (2019) “Recurrence risk of autism in siblings and cousins: A multinational,

population-based study,”

Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent

Psychiatry, 58(9), pp. 866–875.

Hausman-Kedem, M.

et al. (2018) “Accuracy of reported community diagnosis of Autism

Spectrum Disorder,”

Journal of psychopathology and behavioural assessment, 40(3), pp. 367–

375. doi: 10.1007/s10862-018-9642-1.

Hiller, R. M., Young, R. L. and Weber, N. (2014) “Sex differences in autism spectrum disorder

based on DSM-5 criteria: evidence from clinician and teacher reporting,”

Journal of abnormal

child psychology, 42(8), pp. 1381–1393. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9881-x.

Kulage, K. M.

et al. (2020) “How has DSM-5 affected autism diagnosis? A 5-year follow-up

systematic literature review and meta-analysis,”

Journal of autism and developmental

disorders, 50(6), pp. 2102–2127

Maenner, M. J.

et al. (2021) “Prevalence and characteristics of Autism spectrum disorder

among children aged 8 years - Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11

sites, United States, 2018,”

MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 70(11), pp. 1–16.

V0.1 10-12-21

ASD diagnoses

Page 19 of 20

OFFICIAL

Page 19 of 20