FOI 24/25-0380

Sleep/Bedtime .................................................................................................................................... 5

Toddlers 1 – 3 years ................................................................................................................................ 6

Toileting .............................................................................................................................................. 6

Feeding ................................................................................................................................................ 6

Eating .................................................................................................................................................. 6

Dressing ............................................................................................................................................... 6

Behaviours .......................................................................................................................................... 7

Sleep/Bedtime .................................................................................................................................... 8

Pre‐schoolers 3 – 5 years ........................................................................................................................ 9

Toileting .............................................................................................................................................. 9

Feeding ................................................................................................................................................ 9

Eating .................................................................................................................................................. 9

Dressing ............................................................................................................................................... 9

Behaviours (continuation from 1‐3 year old) ..................................................................................... 9

Sleep/Bedtime .................................................................................................................................. 10

Parenting and stress ............................................................................................................................. 11

Where can parents get help? ................................................................................................................ 11

Financial and other impact of disabilities on family ............................................................................. 12

Multiple children (i.e. demand on parents time).................................................................................. 12

Parental Exhaustion .............................................................................................................................. 11

The impact of multiple and complex needs on a family ....................................................................... 12

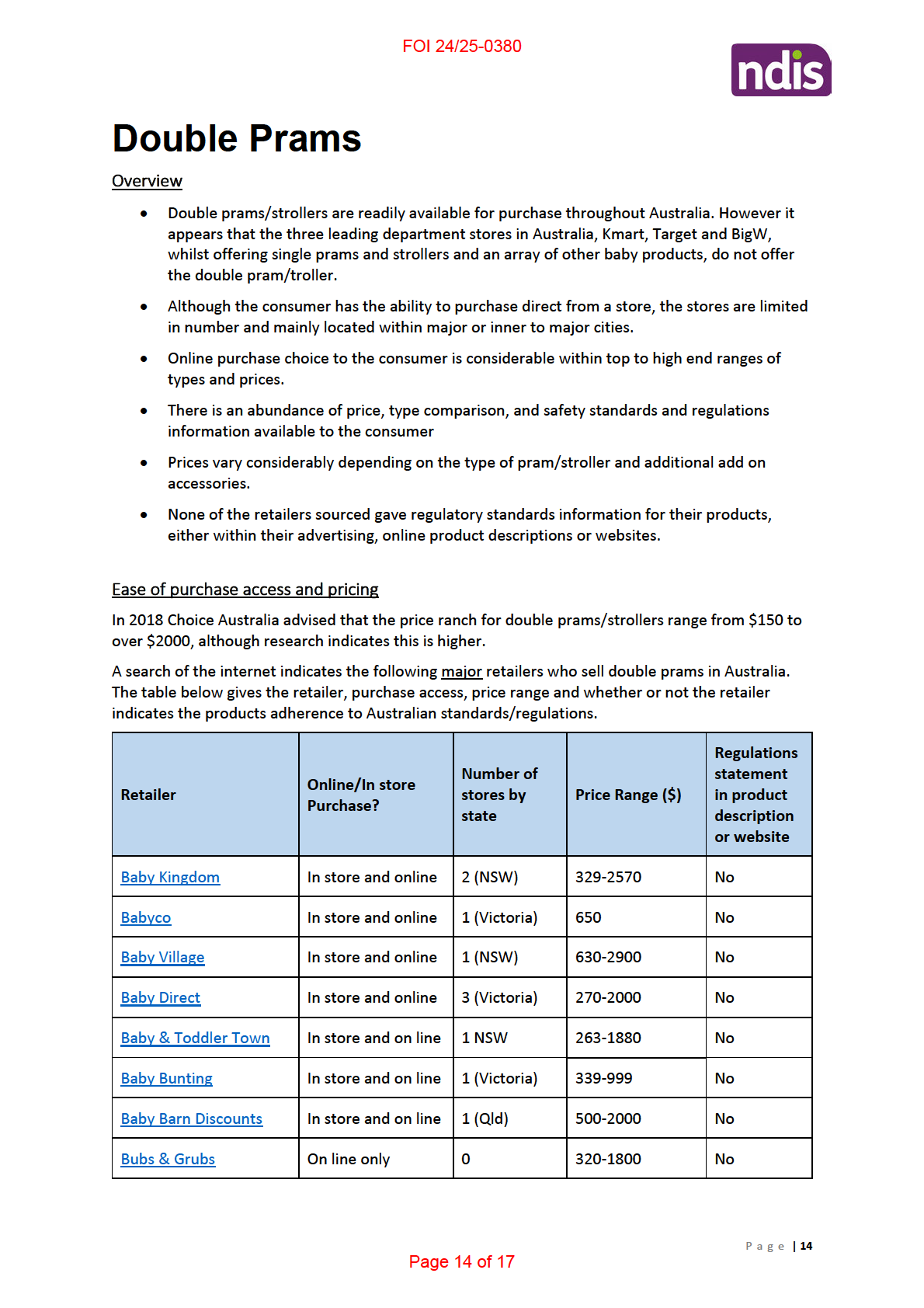

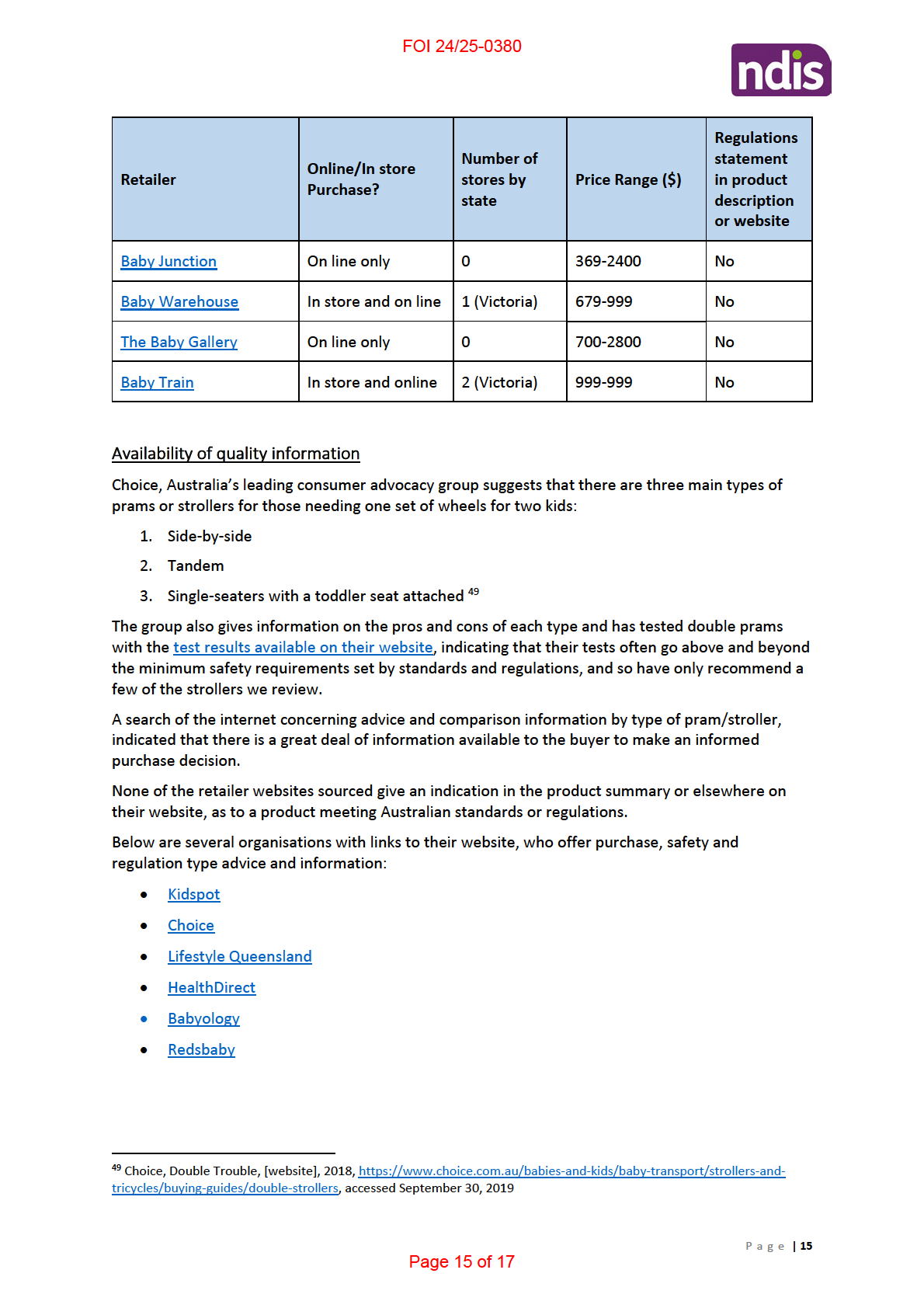

Double Prams ........................................................................................................................................ 14

Overview ........................................................................................................................................... 14

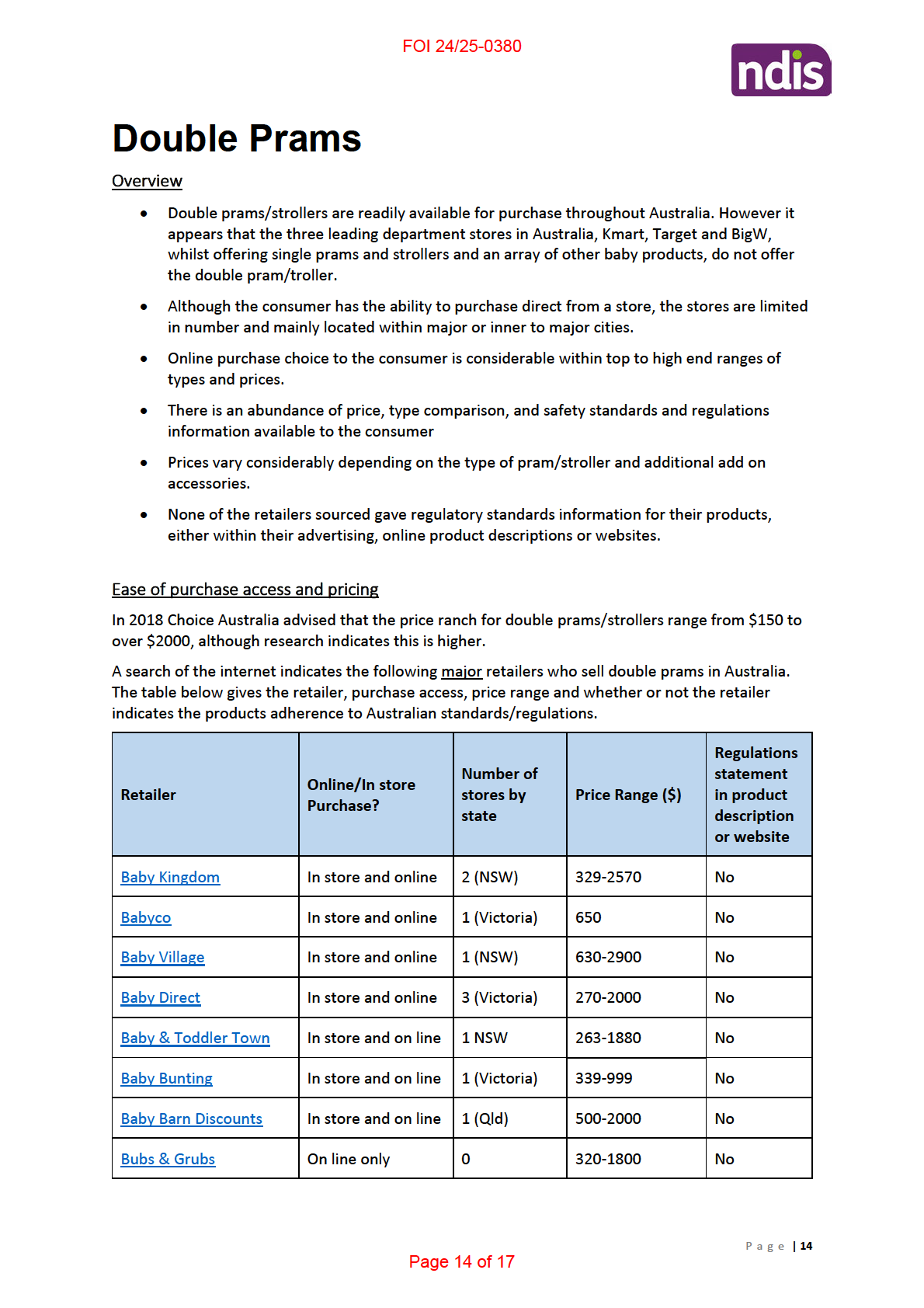

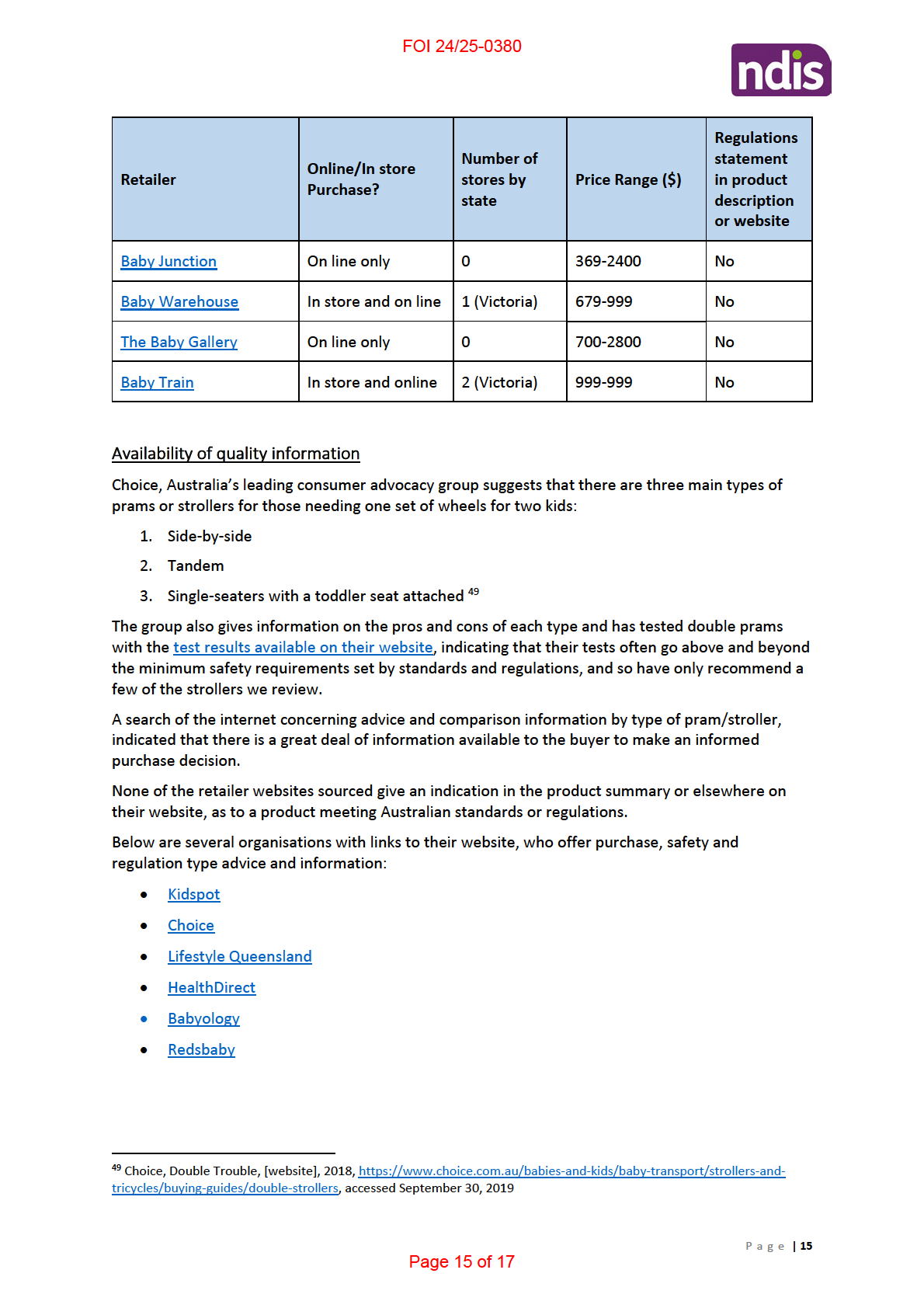

Ease of purchase access and pricing ................................................................................................. 14

Availability of quality information ......................................................................................................... 15

Standards and Regulations ............................................................................................................... 16

Reference List ........................................................................................................................................ 17

P a g e |

2

Page 2 of 17

FOI 24/25-0380

Summary

The information collated below details the typical development stages and behaviours for children

up to age five. It also examines expected challenges that children and their families may experience

during this 0‐5 development phase.

The Raising Children website defines development as:

the changes in a child’s physical growth, as

well as their ability to learn the social, emotional, behaviour, thinking and communication

skills they need for life. All of these areas are linked, and each depends on and influences the

others1.

The majority of information below is taken from the

raisingchildren.net.au website, which provides

free, reliable, up‐to‐date and independent information to help Australians families. It is funded by

the Australian Government, reviewed by experts and is non‐commercial, so it can be considered a

reliable source. Health information is also taken from

healthdirect.gov.au, which is an Australian

government funded service, providing quality, approved health information and advice.

These websites both highlight that all babies, toddlers and children grow and develop at different

rates. The Raising Children website identifies the following key points about child development for

ages 0‐5 years:

Development is how the child grows physically and emotionally and learns to communicate,

think and socialise.

In the first five years of life, the child’s brain develops more and faster than at any other

time in his life.

The parent relationship with the child is one of the most important influences on the child’s

learning and development.

In the early years, the child’s main way of learning and developing is through play2.

For each age bracket, development milestones for toileting, feeding, eating, dressing, behaviours

and sleep/bedtime have been listed.

Babies 3 – 12 months

Toileting

Young babies can wee many times a day. Having lots of wet nappies is a good sign – it shows that a

child is well hydrated. The wetting will happen less as the baby gets older, but it might still happen at

least 6‐8 times a day. Pooing anywhere between three times a day and three times a week is normal.

Generally, a child will need up to 12 nappies changed a day for a newborn and 6‐8 a day for a

toddler3.

Feeding

It is recommended that a mother breastfeed exclusively until the baby starts solid foods at around 6

months and keeps breastfeeding until at least 12 months. A baby needs only small amounts of food

for the first few months of solids, and breastmilk is still a baby’s main source of nutrition. Once a

1 https://raisingchildren.net.au/newborns/development/understanding‐development/development‐first‐five‐years.

2 Ibid.

3 https://raisingchildren.net.au/newborns/health‐daily‐care/poos‐wees‐nappies/nappies

P a g e |

3

Page 3 of 17

FOI 24/25-0380

parent introduces solids, it’s best for the baby if breastfeeding continues along with giving the baby

solids until they are at least 12 months old4.

In the early days, babies typically need to feed every 2‐4 hours. Most babies establish a manageable

pattern of demand feeding over the first few weeks of life. They learn to do most of their feeds

during the day and have fewer at night5.

Eating

Many children are fussy eaters. Fussy eating is normal, but it can be hard to handle. Most of the time

fussy eating isn’t about food – it’s often about children wanting to be independent. Children’s

appetites are affected by their growth cycles. Even babies have changing appetites.

At 1‐6 years, it’s common for children to be really hungry one day and picky the next6.

Dressing

Once a child reaches about 12 months old, they will be very energetic and might not want to stay

still long enough even to put a nappy on, let alone several layers of clothes7.

At one year children can usually:

hold their arms out for sleeves and put their feet up for shoes

push their arms through sleeves and legs through pants

pull socks and shoes off8.

Behaviours

The Raising Children Website identifies the following common behaviour concerns for babies 3‐12

months:

Fear of strangers

o Fear of strangers is normal and common. It can start at around eight months and

usually passes by around two years9.

Separation anxiety

o Separation anxiety is a normal part of development from about eight months of

age10.

Breath holding

o Children might hold their breath when they’re upset or hurt. They don’t do it on

purpose. Breath‐holding spells usually end within 30‐60 seconds11.

Fear of bath

o Newborns might not like the feeling of being in the bath. Older babies and toddlers

might be frightened of the bath12.

4 https://raisingchildren.net.au/babies/breastfeeding‐bottle‐feeding‐solids/about‐breastfeeding/breastmilk‐breastfeeding‐

benefits

5 https://raisingchildren.net.au/babies/behaviour/common‐concerns/can‐you‐spoil‐a‐baby

6 https://raisingchildren.net.au/toddlers/nutrition‐fitness/common‐concerns/fussy‐eating

7 https://raisingchildren.net.au/babies/health‐daily‐care/dressing‐babies/dressing‐baby

8 https://raisingchildren.net.au/toddlers/development/understanding‐development/development‐first‐five‐years

9 https://raisingchildren.net.au/babies/behaviour/common‐concerns/fear‐of‐strangers

10 https://raisingchildren.net.au/babies/behaviour/common‐concerns/separation‐anxiety

11 https://raisingchildren.net.au/babies/behaviour/common‐concerns/breath‐holding

12 https://raisingchildren.net.au/babies/behaviour/common‐concerns/fear‐of‐the‐bath

P a g e |

4

Page 4 of 17

FOI 24/25-0380

Biting, pinching and hair pulling

o Babies bite, pinch and pull hair to work out cause and effect. Toddlers often do it to

express feelings they don’t have words for.13

o Babies and toddlers might also pinch, bite or pull hair if they:

feel overwhelmed by too much noise, light or activity

need opportunities for more active play

feel overtired or hungry.

Shyness

o Some children are naturally shy. This means they’re slow to warm up or

uncomfortable in social situations14.

Overstimulation

o A stimulating environment to play in and explore helps a child to learn and grow. But

sometimes too many activities add up to overstimulation, so downtime is important.

o If a newborn or baby is overstimulated, they might:

be cranky or tired

cry more

seem upset or turn her head away from you

move in a jerky way

clench her fists, wave her arms or kick.15

At 6‐12 months, a baby starts to understand cause and effect and begins to have some control over

their behaviour. This is a good time to start setting gentle limits to form the basis of teaching a child

positive behaviour in the future16.

Sleep/Bedtime

Most babies under six months of age still need feeding and help to settle in the night.

6‐12 months:

As babies get older, they need less sleep.

From about six months, most babies have their longest sleeps at night.

Most babies are ready for bed between 6 pm and 8 pm. They usually take less than 30

minutes to get to sleep, but about 1 in 10 babies takes longer.

At this age, most babies are still having 1‐2 daytime naps. These naps usually last 1‐2 hours.

Some babies sleep longer, but up to a quarter of babies nap for less than an hour17.

Most parents of babies under six months of age are still getting up in the night to feed and

settle their babies. For many this keeps going after six months.

13 https://raisingchildren.net.au/babies/behaviour/common‐concerns/biting‐pinching‐hair‐pulling

14 https://raisingchildren.net.au/babies/behaviour/common‐concerns/shyness

15 https://raisingchildren.net.au/babies/behaviour/common‐concerns/overstimulation

16 https://raisingchildren.net.au/babies/behaviour/understanding‐behaviour/baby‐behaviour‐awareness

17 https://raisingchildren.net.au/babies/sleep/understanding‐sleep/sleep‐2‐12‐months

P a g e |

5

Page 5 of 17

FOI 24/25-0380

Some parents find that this is OK as long as they have enough support and they can catch up

on sleep at other times. For others, getting up in the night over the long term has a serious

effect on them and their family life.

There’s a strong link between baby sleep problems and symptoms of postnatal depression in

women and also postnatal depression in men. But the link isn’t there if parents of babies

with sleep problems are getting enough sleep themselves18.

Toddlers 1 – 3 years

Toileting

A child might display signs that they are ready for toilet training from about

two years on. Some

children show signs of being ready as early as 18 months, and some might be older than two years.

The child will require assistance with timing, hygiene e.g. wiping, encouragement, reminding and

dressing associated with toileting until they are able to self‐manage.

Feeding

Weaning off breastfeeding is suitable for 1‐4 years and it entirely dependent on the mother and

child’s preferences19.

Eating

For this age it is the parent’s responsibility to monitor eating habits and encourage healthy eating.

Children’s appetites are affected by their growth cycles. Even babies have changing appetites. At 1‐6

years, it’s common for children to be really hungry one day and picky the next20.

Messy eating is normal when children are learning to feed themselves. It’s natural for them to start

by using their hands and fingers and then move on to cutlery, cups and plates. Over time, their

muscles and coordination improve, and mealtimes become less messy21.

Dressing

At

two years children can usually:

take off unfastened coats

take off shoes when the laces are untied

help push down pants

find armholes in t‐shirts.

At

2½ years children can usually:

pull down pants with elastic waists

try to put on socks

put on front‐buttoned shirts, without doing up buttons

unbutton large buttons.

At

three years children can usually:

18 https://raisingchildren.net.au/babies/sleep/understanding‐sleep/sleep‐2‐12‐months

19 https://raisingchildren.net.au/toddlers/nutrition‐fitness/common‐concerns/weaning‐older‐children

20 https://raisingchildren.net.au/toddlers/nutrition‐fitness/common‐concerns/fussy‐eating

21 https://raisingchildren.net.au/toddlers/nutrition‐fitness/common‐concerns/messy‐eating

P a g e |

6

Page 6 of 17

FOI 24/25-0380

put on t‐shirts with little help

put on shoes without fastening – they might put them on the wrong feet

put on socks – they might have trouble getting their heels in the right place

pull down pants by themselves

zip and unzip without joining or separating zippers

take off t‐shirts without help

button large front buttons22.

Behaviours

Tantrums

Tantrums are very common in

children aged 1‐3 years. This is because children’s social and

emotional skills are only just starting to develop at this age. Children often don’t have the

words to express big emotions. They might be testing out their growing independence.

So tantrums are one of the ways that young children express and manage feelings, and try to

understand or change what’s going on around them.

Older children can have tantrums too.

This can be because they haven’t yet learned more appropriate ways to express or manage

feelings.

For both

toddlers and older children, there are things that can make tantrums more likely to

happen:

o Temperament – this influences how quickly and strongly children react to things like

frustrating events. Children who get upset easily might be more likely to have

tantrums.

o Stress, hunger, tiredness and overstimulation – these can make it harder for children

to express and manage feelings and behaviour.

o Situations that children just can’t cope with – for example, a toddler might have

trouble coping if an older child takes a toy away.

o Strong emotions – worry, fear, shame and anger can be overwhelming for children23.

Self‐regulation

Self‐regulation is the ability to understand and manage behaviour and reactions. Children

start developing it from around 12 months. As a child gets older, they will be more able to

regulate their reactions and calm down when something upsetting happens, resulting in

fewer tantrums.

Toddlers can wait short times for food and toys. But toddlers might still snatch toys from

other children if it’s something they really want. And tantrums happen when toddlers

struggle with regulating strong emotions24.

Biting, pinching and hair pulling

Toddlers might bite, pinch or pull hair because they’re excited, angry, upset or hurt.

Sometimes they behave this way because they don’t have words to express these feelings.

22 https://raisingchildren.net.au/toddlers/development/understanding‐development/development‐first‐five‐years

23 https://raisingchildren.net.au/toddlers/behaviour/crying‐tantrums/tantrums

24 https://raisingchildren.net.au/preschoolers/behaviour/understanding‐behaviour/self‐regulation

P a g e |

7

Page 7 of 17

FOI 24/25-0380

Some toddlers might bite, pinch or pull hair because they’ve seen other children do it, or

other children have done it to them25

Fear of bath

Older babies and toddlers might be afraid of the noise of the water draining or of slipping

under the water. They might not like having their hair washed or getting water or soap in

their eyes26.

Over stimulation

If a toddler or pre‐schooler is overstimulated, they might:

o seem tired, cranky and upset

o cry and not be able to use words to describe feelings

o throw themselves on the floor in tears or anger

o tell you that they do not want to do a particular activity anymore

o refuse to do simple things like putting on a seatbelt.

Lies

Children can learn to tell lies from an early age, usually around three years of age27.

Swearing

Young children often swear because they’re exploring language. They might be testing a new

word, perhaps to understand its meaning28.

Pestering

Pestering is also common behaviour for 2 – 8 year olds and can sometimes lead to

tantrums29. There are effective parenting techniques to reduce pestering behaviours.

Sleep/Bedtime

Toddlers need about 12‐13 hours of sleep every 24 hours. That’s usually 10‐12 hours at night

and 1‐2 hours during the day.

Common toddler sleep problems include having trouble settling to sleep and not wanting to

stay in bed at bedtime. Other common toddler sleep problems are night terrors, teeth

grinding and calling out after bed time30.

Less than 5% of two‐year‐olds wake three or more times overnight31.

25 https://raisingchildren.net.au/babies/behaviour/common‐concerns/biting‐pinching‐hair‐pulling

26 https://raisingchildren.net.au/babies/behaviour/common‐concerns/fear‐of‐the‐bath

27 https://raisingchildren.net.au/toddlers/behaviour/common‐concerns/lies

28 https://raisingchildren.net.au/toddlers/behaviour/common‐concerns/swearing‐toddlers‐preschoolers

29 https://raisingchildren.net.au/toddlers/behaviour/common‐concerns/pester‐power

30 https://raisingchildren.net.au/toddlers/sleep/understanding‐sleep/toddler‐sleep

31 https://raisingchildren.net.au/school‐age/sleep/understanding‐sleep/about‐sleep

P a g e |

8

Page 8 of 17

FOI 24/25-0380

Pre-schoolers 3 – 5 years

Toileting

Often, children are 3‐4 years old before they’re dry at night. One in 5 five‐year‐olds and one in 10

six‐year‐olds still uses nappies overnight. And bedwetting is very common in school‐age children32.

Faecal incontinence ‐ All children achieve bowel control at their own rate. Faecal incontinence isn’t

generally considered a medical condition unless a child is at least four years old.

Pre‐school age children need to be taught about personal hygiene for washing, drying and toileting.

Feeding

The Raising Children website states that it is up to the parent how long a mother continues to

breastfeed. If a mother decides to breastfeed for longer, the baby will get added benefits like

protection against infections in the toddler years33.

Eating

The Raising Children website provides information about healthy nutrition and fitness choices for

children and teaching health habits. Children of this age are able to decide if they are hungry and

what they would like to eat, but still require parent’s to provide health options and monitor

undereating or overeating34.

Dressing

At

four years children can usually:

take off t‐shirts by themselves

buckle shoes or belts

connect jacket zippers and zip them up

put on socks the right way

put on shoes with little help

know the front and back of clothing.

At

4½ years children can usually:

step into pants and pull them up

thread belts through buckles.

At

five years children can usually:

dress without help or supervision

put on t‐shirts or jumpers the right way each time

Tying up shoelaces is a skill that most five‐year‐olds are still learning35.

Behaviours (continuation from 1‐3 year old)

Self‐regulation

32 https://raisingchildren.net.au/preschoolers/health‐daily‐care/toileting/toilet‐training‐guide

33 https://raisingchildren.net.au/babies/breastfeeding‐bottle‐feeding‐solids/about‐breastfeeding/breastmilk‐

breastfeeding‐benefits

34 https://raisingchildren.net.au/preschoolers/nutrition‐fitness/healthy‐eating‐habits/healthy‐eating‐habits

35 https://raisingchildren.net.au/preschoolers/health‐daily‐care/dressing/how‐to‐get‐dressed

P a g e |

9

Page 9 of 17

FOI 24/25-0380

Children develop self‐regulation through warm and responsive relationships. They also

develop it by watching the adults around them.

Self‐regulation starts when children are babies. It develops most in the toddler and

preschool years, but it also keeps developing right into adulthood.

Pre‐schoolers are starting to know how to play with other children and understand what’s

expected of them. For example, a pre‐schooler might try to speak in a soft voice if you’re at

the movies.

School‐age children are getting better at controlling their own wants and needs, imagining

others people’s perspectives and seeing both sides of a situation. This means, for example,

that they might be able to disagree with other children without having an argument36.

Tantrums

If a child has tantrums, it might help to know that this behaviour is still very common among

children aged 18‐36 months. Hang in there – tantrums tend to lessen after children turn

four.

Habits and lying

Lying is part of a child’s development, and it often starts around three years of age. Children

aged 4‐6 years usually lie a bit more than children of other ages.

Anxiety

Anxiety is a normal part of children’s development, and pre‐schoolers often fear being on

their own and in the dark.

Children may also experience separation anxiety and social anxiety and phobias37.

Imaginary friend

It is common for children to have an imaginary friend at this age. Make‐believe mates grow

out of healthy, active imaginations, give children a great way to express their feelings, and

give children someone to practise social skills with38.

Sleep/Bedtime

Most pre‐schoolers need 11‐13 hours of sleep a night, and some still nap during the day.

Pre‐schoolers sometimes have sleep problems like getting out of bed, as well as nightmares

and night terrors39.

It is a parent’s responsibility to establish a sleep schedule and minimise factors that prevent

sleep40.

36 https://raisingchildren.net.au/preschoolers/behaviour/understanding‐behaviour/self‐regulation

37 https://raisingchildren.net.au/preschoolers/health‐daily‐care

38 https://raisingchildren.net.au/preschoolers/behaviour/understanding‐behaviour/preschooler‐behaviour

39 https://raisingchildren.net.au/preschoolers/sleep/understanding‐sleep/preschooler‐sleep

40 Health Direct, ‘Sleep tips for children’, December 2017, https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/sleep‐tips‐for‐children,

accessed 1 October 2019.

P a g e |

10

Page 10 of 17

FOI 24/25-0380

Parenting and stress

Parental Exhaustion

Parental burnout is a specific syndrome resulting from enduring exposure to chronic parenting

stress. It encompasses three dimensions: an overwhelming exhaustion related to one's parental role,

an emotional distancing from one's children and a sense of ineffectiveness in one's parental role41.

Available information indicates that this is a relatively new area of research and the impacts of

parental burnout have not been accurately measured. The research to date has mostly been

measured by self‐reporting about lived experience throughout a set period of time.

The Australian Institute of Family Studies have recently studied parenting efficacy, which is ‘a

parent's belief in their effectiveness as a parent’. This research has found a direct link between the

parents perception of ‘high parenting efficacy’ with:

1) greatest level of community support

2) perceived financial status as being prosperous/very comfortable

3) high level of partner support; and

4) enough help from family and friends42.

The research concluded:

“The importance of local community support, financial support, family and friend support,

and marital support for parenting efficacy. Parents with greater local community support,

positive financial status, strong social network and a supportive partner reported higher

levels of parenting efficacy.

Local community supports and resources, such as community‐based parenting services, play

an important role in building parenting efficacy and should be accessible for all parents.

Local councils could provide information about these services through newsletters and

advertisements.

Interventions that focus on helping parents have better financial capacity and help in

relieving financial pressures for them are also important. For instance, current policies such

as paid maternity leave and family tax benefits should help parents cope with decreased

income when they need to reduce working hours to perform parenting tasks.

An important part of support interventions can involve assisting parents to develop new

relationships with people in their social networks and to help them enlarge their social

networks by making new friends. For example, local community activities such as "street

parties" or activities at neighbourhood houses can be encouraged as parents are often able

to meet other parents who can help them to make friends and enlarge their social networks.

Strengthening parents' partnerships is an effective aspect of parenting efficacy, and

interventions could increase marital support through developing co‐parenting awareness

and skills to better support each other. For example, postnatal parenting support groups,

parenting workshops and telephone helplines could be beneficial to parents”43.

41 Mikolajczak, M et al, ‘Consequences of parental burnout: Its specific effect on child neglect and violence, Child Abuse

and Neglect, vol. 80, June 2018, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29604504>, pp‐134‐145.

42 Yu, M, Parenting efficacy: How can service providers help?, Family Relationships Quarterly, No 19, Australian Institute of

Family Studies, 2011, https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/family‐relationships‐quarterly‐no‐19/parenting‐efficacy‐how‐

can‐service‐providers‐help

43 Ibid.

P a g e |

11

Page 11 of 17

FOI 24/25-0380

Financial and other impact of disabilities on family

The Australian Institute for Professional Counsellors state that:

“Some family members, especially mothers, experience more stress and a change to their

wellbeing than families who do not have children with disabilities. Time and emotional

commitments associated with raising a child with high support needs are usual sources of

this stress. Mothers and fathers benefit significantly, both financially and emotionally, from

receiving additional informal and formal support. While access to formal support services is

crucial to parents, mothers have also described emotional support as possibly the most

helpful coping factor”44.

Multiple children (i.e. demand on parents time)

A recent study from 2018 published in the Journal of Marriage and Family, titled

‘Harried and

Unhealthy? Parenthood, Time Pressure, and Mental Health’, investigated the effects of first and

second births on time pressure and mental health and how these vary with time since birth and

parental responsibilities. It also examines whether time pressure mediates the relationship between

parenthood and mental health.

The research found that:

Children have a stronger effect on mothers' than fathers' experiences of time pressure.

These differences are not moderated by changes in parental responsibilities or work time

following births. The increased time pressure associated with second births explains

mothers' worse mental health45.

Researchers expected the introduction of a second and subsequent children to increase the

demand of the parents' role, while bringing less pressure and stress due to developed

parenting skills gained from their first child. However, research revealed significant time

pressure increases for both parents following the birth of their first child (with mothers

showing substantially larger time pressures than fathers). The birth of their second child

doubled time pressure for both parents, further widening the gap between mothers and

fathers46.

The impact of multiple and complex needs on a family

The Victorian Government Department of Human Services have published a document titled

‘Families with multiple and complex needs: best interests case practice model – Specialist practice

resource’, which is a practice model for professionals for working with children and families. While it

is framed in a child protection context, it offers information about the dynamics of families for

complex needs.

Some key passages from the resource about parenting stress factors:

44 The Australian institute of Counsellors, Trends and Statistics of the Contemporary Family, 2012,

https://www.aipc.net.au/articles/trends‐and‐statistics‐of‐the‐contemporary‐family/

45 Ruppanner, L et al, ‘Harried and Unhealthy? Parenthood, Time Pressure, and Mental Health, Journal of Marriage and

Family, 2018, National Council on Family Relations, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jomf.12531

46 Gifford, BE, ‘research reveals having a second child worsens parental stress and mental health’, Happiful, December

2018, https://happiful.com/research‐reveals‐having‐a‐second‐child‐worsens‐parental‐stress‐and‐mental‐health/

P a g e |

12

Page 12 of 17

FOI 24/25-0380

The main challenges for parents experiencing multiple and complex needs are the capacity

to care for their children and parent effectively.

Parents are likely to be preoccupied by attempts to deal with and manage pressures, so they

are not able to give parenting the attention needed or to parent effectively, and their

parenting capacity becomes depleted or compromised.

Their parenting may include disengaged, unresponsive, inappropriate, harsh, punitive or

abusive responses to children. Couple relationships may be under extreme pressure and

subsequently become conflict‐ridden and unstable, and both couples and single parents may

lack sufficient family and social supports.

Parents’ own poor experience of parenting and absence of good parenting models to

replicate, may also affect their responses to children and parenting capacity. To make

matters more complicated, family members may be experiencing the same stressors but

they present with different reactions, behaviours and problems linked to those stressors and

linked to each other’s behaviour and problems.

Over time, the stress, compounding difficulties and cumulative impacts mean that a family

can struggle to function, experiencing periodic crises, intensification of individual and family

relationship problems, role disintegration or family fragmentation.

As family members become increasingly overwhelmed, the effect on individual functioning

and on family dynamics can exacerbate contexts in which family violence, substance abuse,

mental illness and child abuse occur or escalate47.

Where can parents get help?

The Better Health Channel (Victoria) suggests parents can seek help from the following sources:

Your doctor

Your partner

Family members and friends

Parentline Tel. 132 289

Family Relationship Advice Line Tel. 1800 050 321 Monday to Friday, 8am to 8pm, Saturday,

10am to 4pm

This way up ‐ an online

Coping with Stress and an

Intro to Mindfulness course developed by the

Clinical Research Unit of Anxiety and Depression (CRUfAD) at St Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney and

University of New South Wales (UNSW) Faculty of Medicine.

Maternal and child health nurse

Your local community health centre

Professionals such as counsellors48.

Most state and territory health and family support agencies have this information readily available.

47Victorian Government Department of Human Services, ‘Families with multiple and complex needs: best interests case

practice model – Specialist practice resource’, 2012,

https://www.cpmanual.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/Families%20with%20multiple%20%26%20complex%20needs%20spec

ialist%20resource%203016%20.pdf

48 Better Health Channel, ‘Parenting and Stress’, 2014,

https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/healthyliving/parenting‐and‐stress

P a g e |

13

Page 13 of 17

FOI 24/25-0380

Standards and Regulations

The Australian New Zealand Standard AS/NZS 2088:2000 requires prams and strollers sold in

Australia comply with provisions for:

safety restraints

brakes

tether straps

safety labelling

testing procedures. 50

The ACCC has completed a review on the mandatory safety standards for prams and strollers and is

currently preparing advice to the Minister. The mandatory standard prescribes requirements for the

performance testing, design, construction, safety warnings and labels of prams and strollers. 51

Public transport departments also offer guidelines for safety of prams and strollers whilst using

public transport, such as Kidsafe NSW, Public Transport Victoria and NSW Transport.

50 NSW Government, Fair Trading: Baby Products, [website], 2019, https://www.fairtrading.nsw.gov.au/buying‐products‐

and‐services/product‐and‐service‐safety/childrens‐products/baby‐products, accessed September 30 2019.

51 ACCC, Product Safety Australia: Prams & Strollers, [website], 2019, https://www.productsafety.gov.au/standards/prams‐

strollers, accessed September 30 2019.

P a g e |

16

Page 16 of 17

FOI 24/25-0380

Reference List

Australian Competition and Consumers Commission, Product Safety Australia: Prams & Strollers, [website], 2019,

https://www.productsafety.gov.au/standards/prams‐strollers, accessed September 30 2019.

Better Health Channel, ‘Parenting and Stress’, 2014, https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/healthyliving/parenting‐

and‐stress

Choice, Double Trouble, [website], 2018, https://www.choice.com.au/babies‐and‐kids/baby‐transport/strollers‐and‐

tricycles/buying‐guides/double‐strollers, accessed September 30, 2019

Gifford, BE, ‘research reveals having a second child worsens parental stress and mental health’, Happiful, December 2018,

https://happiful.com/research‐reveals‐having‐a‐second‐child‐worsens‐parental‐stress‐and‐mental‐health/

Health Direct, ‘Sleep tips for children’, December 2017, https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/sleep‐tips‐for‐children, accessed

1 October 2019.

Mikolajczak, M et al, ‘Consequences of parental burnout: Its specific effect on child neglect and violence, Child Abuse and

Neglect, vol. 80, June 2018, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29604504>, pp‐134‐145.

Multiple Raising Children web pages – as hyperlinked in footnotes.

NSW Government, Fair Trading: Baby Products, [website], 2019, https://www.fairtrading.nsw.gov.au/buying‐products‐and‐

services/product‐and‐service‐safety/childrens‐products/baby‐products, accessed September 30 2019.

Ruppanner, L et al, ‘Harried and Unhealthy? Parenthood, Time Pressure, and Mental Health, Journal of Marriage and

Family, 2018, National Council on Family Relations, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jomf.12531

The Australian institute of Counsellors, Trends and Statistics of the Contemporary Family, 2012,

https://www.aipc.net.au/articles/trends‐and‐statistics‐of‐the‐contemporary‐family/

Victorian Government Department of Human Services, ‘Families with multiple and complex needs: best interests case

practice model – Specialist practice resource’, 2012,

https://www.cpmanual.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/Families%20with%20multiple%20%26%20complex%20need

s%20specialist%20resource%203016%20.pdf

Yu, M, Parenting efficacy: How can service providers help?, Family Relationships Quarterly, No 19, Australian Institute of

Family Studies, 2011, https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/family‐relationships‐quarterly‐no‐19/parenting‐

efficacy‐how‐can‐service‐providers‐help

P a g e |

17

Page 17 of 17