FOI 24/25-0380

DOCUMENT 11

Research Paper

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

Animal Assisted Therapy and Assistance

Animals

The content of this document is OFFICIAL.

Please note:

The research and literature reviews collated by our TAB Research Team are not to be shared

external to the Branch. These are for internal TAB use only and are intended to assist our

advisors with their reasonable and necessary decision-making.

Delegates have access to a wide variety of comprehensive guidance material. If Delegates

require further information on access or planning matters, they are to call the TAPS line for

advice.

The Research Team are unable to ensure that the information listed below provides an

accurate & up-to-date snapshot of these matters

Research questions:

1. Are there best practice models for animal assisted therapy that promote client

independence and self-management?

2. What is the role of animal assisted therapy to promote capacity building that results in

independence after therapy has ended?

3. Is there evidence of stigma or prejudice with the use of assistance animals?

4. Is there evidence of negative outcomes when assistance animals draw unwanted attention?

Date: 14/4/2022

Requestor: S47F -

Endorsed by (EL1 or above):

Researcher: S47F - Personal

Cleared by: S47F - Personal

1.

Contents

Animal Assisted Therapy and Assistance Animals .................................................................... 1

1.

Contents ....................................................................................................................... 1

2.

Summary ...................................................................................................................... 2

3.

Animal Assisted Therapy .............................................................................................. 2

3.1

Regulation of animal assisted therapy ....................................................................... 2

V1 14-04-2022

Animal Assisted Therapy

Page 1 of 9

OFFICIAL

Page 1 of 9

FOI 24/25-0380

Research Paper

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

3.2

Models of best practice using animal therapy to promote independence .................. 3

3.3

Capacity building using animal therapy ..................................................................... 3

3.4

Ending the therapeutic relationship ........................................................................... 5

4.

Assistance Animals ....................................................................................................... 5

4.1

Stigma and discrimination .......................................................................................... 5

5.

References ................................................................................................................... 8

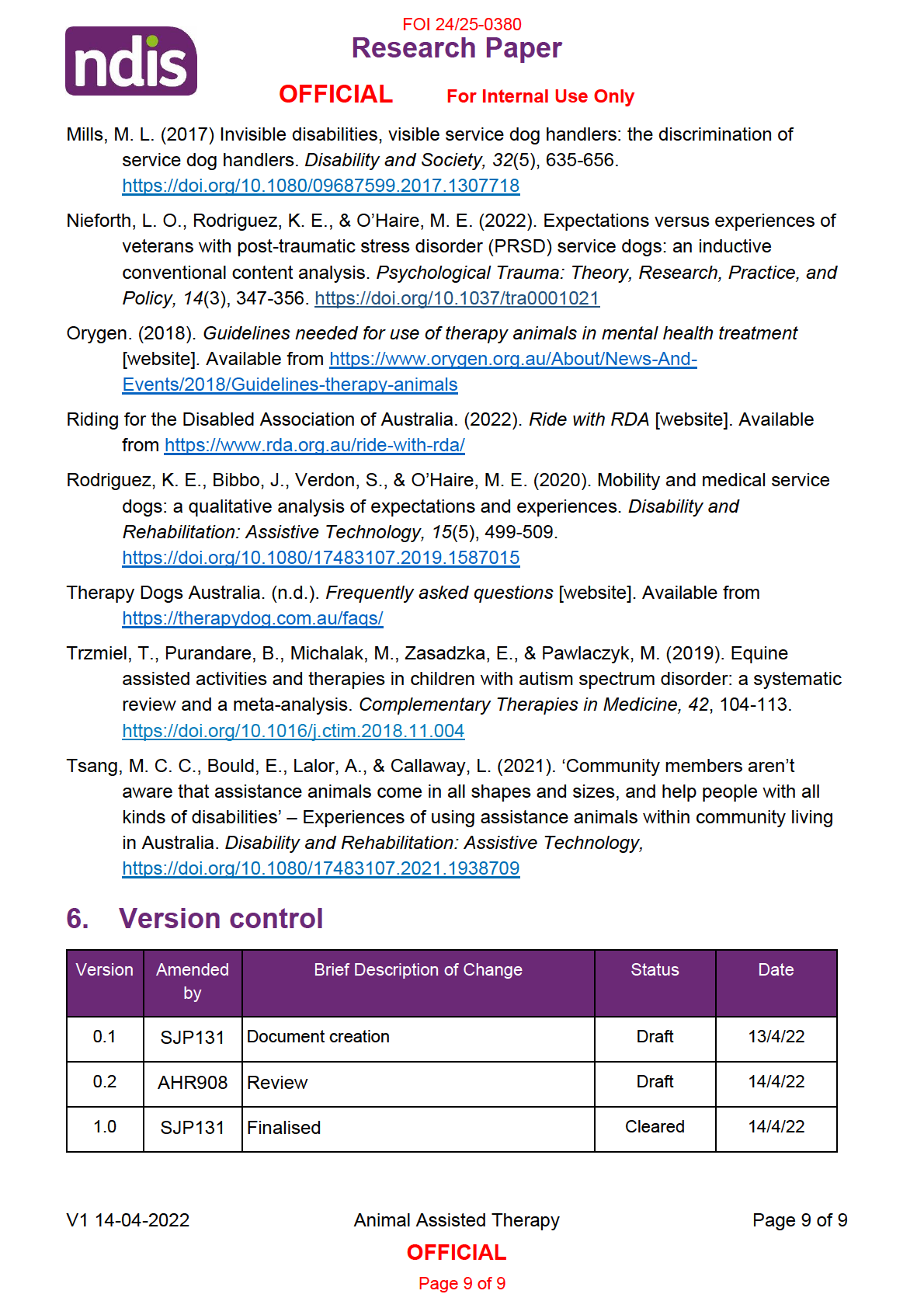

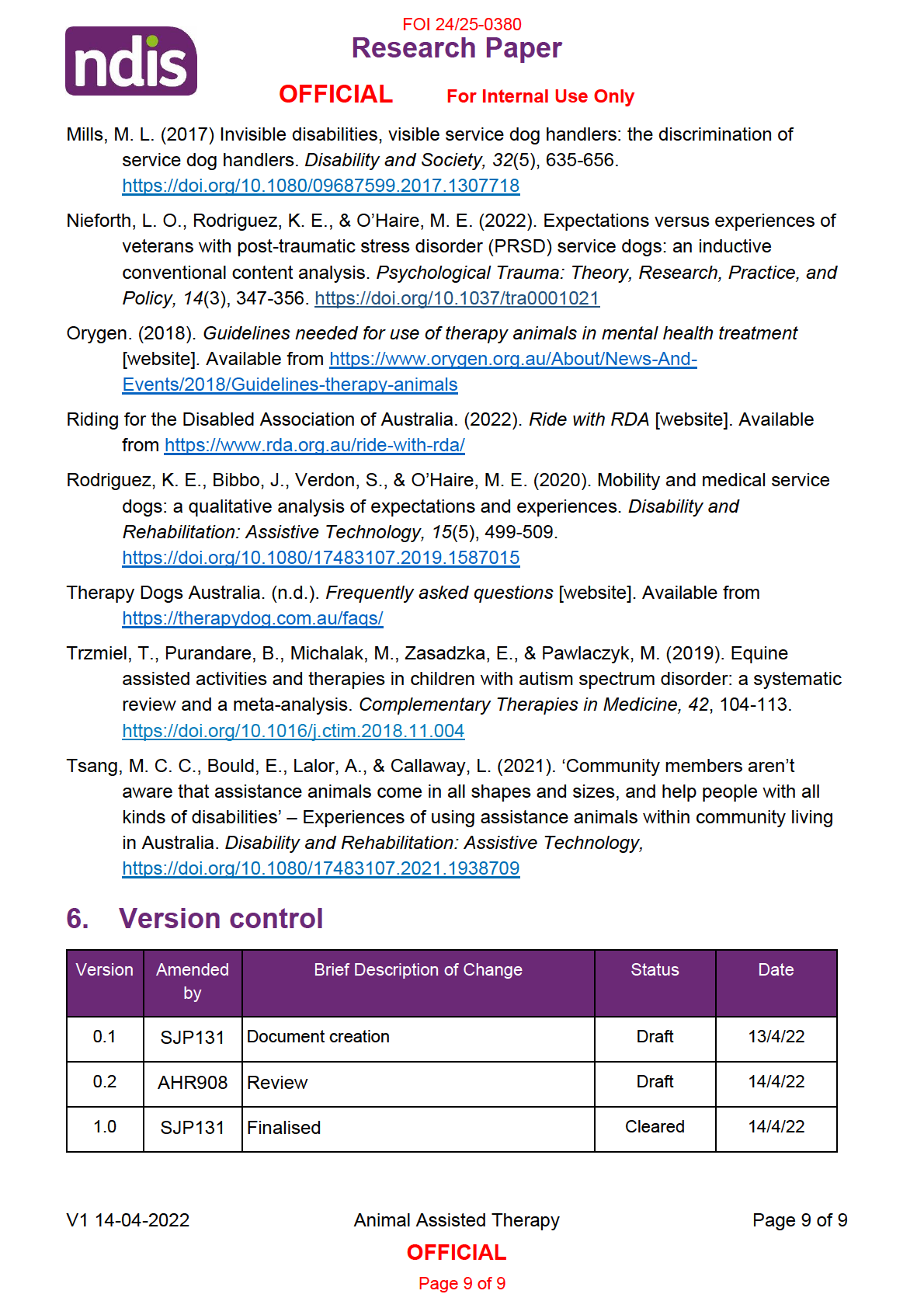

6.

Version control .............................................................................................................. 9

2. Summary

This paper is a supplement to research completed by the Tactical Research Team in 2021 -

RES183 - Therapy Animals - Models of practice for ending involvement in therapy programs

V1.0.docx.

Animal assisted therapy (AAT) is not governed by legislation or industry regulations. AAT

needs to be adapted to individual client needs, therefore there is no model of best practise in

the literature particularly with respect to capacity building for independence. The long-term

efficacy of AAT after the cessation of the therapeutic relationship cannot be determined due to

a lack of information in the literature. It is also unclear how often AAT leads to a request for an

NDIS funded assistance animal as a result of dependence on the therapy animal.

People with a disability experience discrimination and research suggests that use of assistive

technology can lead to discrimination and stigma beyond the disability itself. Research has

shown that people with an invisible disability experience greater discrimination and stigma

when using assistance animals compared to individuals with a visible disability. However, both

groups report challenges and negative experiences as a result of taking their assistance

animal out in public. This includes personal questions, confrontation about access to venues

and people wanting to interact with the assistance animal. While there is limited data regarding

the long-term impact of these negative experiences, it has been reported that these

experiences can be so frustrating or upsetting that it can lead to not taking their assistance

animal out in public as a means to avoid these situations.

3. Animal Assisted Therapy

3.1 Regulation of animal assisted therapy

Therapy dogs are not required to meet any legislated standard in Australia, including

behaviour or hygiene standards (Friendly Dog Collar, 2022). After a broad search of state and

national literature, no industry regulations could be found.

V1 14-04-2022

Animal Assisted Therapy

Page 2 of 9

OFFICIAL

Page 2 of 9

FOI 24/25-0380

Research Paper

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

A search of Australian professional body websites, such as Australian Health Practitioner

Registration Agency, Australian Veterinary Association and Allied Health Professional

Association, revealed an absence of resources in the area of AAT.

It has been recognised by some members in the industry that best-practice regulations for AAT

are needed (Orygen, 2018). The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health

highlight that the absence of regulations make it vulnerable to poor practice for both users and

those delivering the service. Regulations would help the industry operate in a safe and ethical

manner based on evidence (Orygen, 2018).

Despite the lack of industry regulations, there are animal training organisations in Australia

offering courses and assessment certificates for practitioners who want to train their own dog

for use during AAT, such as Therapy Dogs Australia and Therapy Animals Australia. Therapy

Dogs Australia also offer yearly assessment to maintain their organisation’s accreditation

(Therapy Dogs Australia, n.d.).

An international search for regulations revealed Animal Assisted Intervention International

endeavouring to establish practice standards for the industry (AAII, 2019) and International

Society of Animal Assisted Therapy (ISAAT, n.d.) offering accredited training and education for

AAT. However, no international legislation or industry regulations for AAT were found.

3.2 Models of best practice using animal therapy to promote

independence

A search of the literature was unable to reveal a model of best-practice for animal assisted

therapy. A widely recognised definition of AAT is ‘goal directed interventions in which an

animal meeting specific criterion is an integral part of the treatment process’ (Dunlap, 2019).

AAT is considered an adaptive treatment model and is required to be flexible to tailor to

individual goals (Compitus, 2021). AAT is used to improve the social, emotional and cognitive

adaptive functioning of an individual and should be guided by goals and objectives laid out in a

formal treatment plan (Compitus, 2021; Evans and Gray, 2012). AAT is provided in addition to

existing practice models therefore, as practitioners work within their area of expertise of

professional practice, there are variations in how AAT is utilised in practice (Evans & Gray,

2012). As a result, the focus of research is often towards the outcomes of assisted animal

therapy rather than specifics around how the AAT was implemented (Compitus, 2021).

3.3 Capacity building using animal therapy

3.3.1 Why use animals?

It has been postulated that animals may facilitate the therapeutic alliance between client and

practitioner (Compitus, 2021). The basis of AAT is derived from theory of human-animal

interaction, which is the mutual relationship between humans and animals resulting in positive

physical and psychological health (Hill et al, 2020). The benefits of AAT is well represented in

the literature across a range of disabilities and diagnoses, including for hearing and vision

V1 14-04-2022

Animal Assisted Therapy

Page 3 of 9

OFFICIAL

Page 3 of 9

FOI 24/25-0380

Research Paper

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

impairment, physical disability, epilepsy and diabetes alert, autism spectrum disorder, post-

traumatic stress disorder and other psychosocial disabilities (Department of Psychology and

Counselling, School of Psychology and Public Health, 2016; Kourkourikos et al, 2019).

Engaging children with autism spectrum disorder to be actively involved in their therapy can be

difficult and traditional reward systems, such as tokens or stickers, have limited success in

sustaining engagement and positive behaviour (Hill et al, 2020). A systematic review

examining the efficacy of AAT for children with autism spectrum disorder has shown moderate

effect sizes for positive outcomes such as behaviour modification, emotional wellbeing and

autism spectrum symptoms (Burgoyne et al, 2014). Further studies have shown improvement

in social engagement for these children, including increased verbal and non-verbal

communication, when interacting with a therapy dog (Hill et al, 2020; Kourkourikos et al, 2019).

Research has also demonstrated that equine therapy may improve social functioning, reduce

maladaptive behaviour and increase trunk stability for children with autism spectrum disorder

(Trzmiel et al, 2019).

Social and emotional benefits from AAT have been attributed to the human-animal bond

whereby the non-judgemental nature of animals encourages people to seek support and

companionship from animals (Ferrell & Crowly, 2021). AAT may act as a motivator to attend

and engage in therapy, particularly for children or people with a psychosocial disorder who

might increase their attention and participation with the therapy program (Hill et al, 2020).

Animal therapy can also have physical benefits for individuals with physical challenges,

including improving fine motor skills from grooming or strengthened muscles and improved

coordination through horse riding (Kourkourikos, 2019; Riding for the Disabled, 2022).

3.3.2 Canine-assisted animal therapy

Dogs are the most common animal used for animal assisted therapy, possibly due to their

ability to be bred to certain physical traits, temperament and willingness to be around people

and the historical point, now outdated, that dogs were the only species to have legal

recognition as an assistance animal (La Trobe University, 2016).

As detailed in 3.1 Regulation of animal assisted therapy, there are training providers in

Australia who will train an individual’s dog to be a therapy dog for clinical work. General canine

assisted therapy programs have not been discovered through this research, possibly because

a therapy dog’s work with a client depends on the skills of the practitioner and needs of the

client (Compitus et al, 2021; Evans & Gray, 2012). A literature search also has not identified

research regarding long term maintenance of capacity building gains through canine assisted

therapy, therefore the long-term efficacy of canine assisted therapy programs cannot be

determined.

3.3.3 Riding for the Disabled

Riding for the Disabled provides equine therapy for people with a disability. Resources

provided by Riding for the Disabled indicate they cater to individuals with a range of intellectual

and physical disabilities, including cerebral palsy, autism spectrum disorder and spina bifida

V1 14-04-2022

Animal Assisted Therapy

Page 4 of 9

OFFICIAL

Page 4 of 9

FOI 24/25-0380

Research Paper

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

(Riding for the Disabled Association of Australia, 2022). The organisation indicates there are

capacity building benefits across physical, social, psychological and educational domains

(Riding for the Disabled, 2022), however there is no information about their specific riding

programs such as how often or how many therapy sessions are required to achieve the stated

benefits. Also, the organisation does not provide information on their website about how

capacity building gains are maintained after cessation of the AAT program.

3.4 Ending the therapeutic relationship

While there is a broad range of literature describing the positive outcomes of animal assisted

therapy, there is little research in the area of ending the therapeutic relationship. One study,

Compitus et al (2021), addresses the need to prepare the client for the end of the therapeutic

relationship however does not address how the end of therapy is managed in a way that

ensures capacity building gains are maintained. It was noted that for clients with strong

attachment to the animal, or a history of insecure attachment, ending AAT needed to occur

after emotional regulation skills had been developed so there was not a sense of loss when

separating from the therapy animal (Compitus et al, 2021).

A broad literature search was unable to discover longitudinal research regarding maintenance

of the skills developed during animal assisted therapy, therefore no conclusions can be made

with respect to the long-term efficacy of animal assisted therapy. Also, research regarding how

often AAT leads to a request for an assistance animal on a permanent basis could not be

sourced. Therefore, it cannot be determined how often an individual may become dependent

on an assistance animal to maintain their functional capacity gains.

4. Assistance Animals

4.1 Stigma and discrimination

There is a rich volume of literature regarding the many benefits, including increased emotional

and functional capacity, for people who are supported by an assistance animal (Nieforth et al,

2021; Rodriguez et al, 2020; Tsang et al, 2021). Assistance animals can support people

across a range of ‘visible’ and ‘invisible’ disabilities, such as blindness, hearing impaired,

autism spectrum disorder, epilepsy and psychosocial disabilities (Kourkourikos, 2019; Tsang

et al, 2021). There is increasing research exploring challenges that result from using an

assistance animal in the community, particularly for people with an ‘invisible’ disability,

including stigma and discrimination (Nieforth et al, 2021; Rodriguez et al, 2020; Tsang et al,

2021).

Mills (2017) conducted research specifically whether the visibility of a disability impacts the

assistance animal user’s experience with respect to discrimination. It was found that 61.1% of

respondents with an invisible disability reported everyday discrimination, compared to 39.7%

with a visible disability. Invasive questions were reported by 76.9% of respondents with an

invisible disability and 56.5% of respondents with a visible disability. Unwanted attention was

V1 14-04-2022

Animal Assisted Therapy

Page 5 of 9

OFFICIAL

Page 5 of 9

FOI 24/25-0380

Research Paper

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

received by 52.9% of individuals with an invisible disability compared to 29.4% of individuals

with a visible disability. Use of assistance animals for people with an invisible disability means

the disability is no longer concealed but as the disability is still not easily identified it may make

these assistance animal users more vulnerable to discrimination due to scepticism about the

legitimacy of their need for the assistance animal (Mills, 2017).

Although individuals with an invisible disability may be more likely to experience discrimination

when using their assistance animal in public, discrimination is still reported by individuals with

a visible disability. In a 2020 study by Rodriguez et al investigating the experience of 64 people

with an assistance dog – disabilities included epilepsy, musculoskeletal disorder and

neuromuscular disorder – only 30% said there were no negative points to having an

assistance animal. Challenges described by the participants included public access and

education (44% of the cohort) and negative attention received from people while in public

(20%). Participants cited issues such as people patting or distracting their assistance dog,

people making assumptions about their functional capacity, and the lack of understanding that

assistance animals can be utilised for people other than blind or hearing impaired.

Supporting these findings, Tsang et al (2021) found with a cohort of 112 Australian participants

with a disability – disabilities included psychosocial disability, autism spectrum disorder,

physical disability, diabetic alert, hearing, seizure response and other neurological – 70% of

participants experienced both positive and negative experiences in the community with their

assistance animal. Almost all participants experienced being asked why they had an

assistance animal. Apart from the hearing-impaired participants, at least 50% of the other

disability groups reported being verbally discriminated (being insulted or joked about). Non-

verbal discrimination, such as being stared at or path avoidance, was reported at higher rates

particularly for people with autism and seizure response dogs. Unwanted attention included

people distracting the dog or trying to pat the dog, being asked personal questions about their

disability and unwanted social interactions with strangers were reported to sometimes be a

barrier to accessing the community with their assistance dog. Further challenges reported,

explained in part that it might occur when a common or expected dog breed is not used as the

assistance animal, were being refused access to taxis, bus drivers not stopping when they see

the assistance dog, difficulty booking accommodation, and accessing retail and hairdressers.

A further study by Nieforth et al (2022) explored the experiences of 69 US Veterans with post-

traumatic stress disorder who had an assistance dog and found 43% received too much

attention and were asked personal questions by strangers, 25% experienced misinformation

about service dogs including being accused of having the legitimacy of their dog questioned,

and 6% reported stigma when out in the community.

Long term implications from these negative experiences are not well documented with respect

to whether they may trigger a relapse (or worsening) of symptoms for people with a

psychosocial disability. However, it has been stated there is a need to be assertive when in

public with an assistance animal as there may be confrontations when trying to access venues

or transport, and these confrontations may cause considerable stress for people with an

V1 14-04-2022

Animal Assisted Therapy

Page 6 of 9

OFFICIAL

Page 6 of 9

FOI 24/25-0380

Research Paper

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

anxiety disorder (Department of Psychology and Counselling, School of Psychology and Public

Health. (2016). Mills (2017) and Tsang et al (2021) both reported some individuals with an

assistance animal become so bothered by the personal questions and difficulties with public

access that they make the personal choice to not take their assistance animal in public.

Therefore, it seems reasonable to conclude that these people could experience worsening

symptoms of their psychosocial disorder as time goes on.

V1 14-04-2022

Animal Assisted Therapy

Page 7 of 9

OFFICIAL

Page 7 of 9

FOI 24/25-0380

Research Paper

OFFICIAL

For Internal Use Only

5. References

Animal Assisted Intervention International. (2019).

Animal Assisted Intervention International

Standards of Practice. Available from https://otaus.com.au/publicassets/80cfd523-2030-

ea11-9403-005056be13b5/AAII-Standards-of-Practice.pdf

Burgoyne, L., Dowling, L., Fitzgerald, A., Connolly, M., Browne, J. P., & Perry, I. J. (2014).

Parents’ perspectives on the value of assistance dogs for children with autism spectrum

disorder: A cross sectional study.

BMJ Open, 4, e004786. Doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-

004786

Compitus, K. (2021). The process of integrating animal-assisted therapy into clinical social

work practice.

Clinical Social Work Journal, 49, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-019-

00721-3

Department of Psychology and Counselling, School of Psychology and Public Health. (2016).

Reviewing assistance animal effectiveness: literature review, provider survey,

assistance animal owner interviews, health economics analysis and recommendations.

Final report to National Disability Insurance Agency. La Trobe University.

Dunlap, K. B., Miller, K. D., & Kinney, J. S. (2021). Recreational therapists’ practice,

knowledge, and perceptions associated with animal-assisted therapy.

Therapeutic

Recreation Journal, LV(4), 384-398. https://doi.org/10.18666/TRJ-2021-V55-I4-11058

Evans, N., & Gray, C. (2012). The practice and ethics of animal-assisted therapy with children

and young people: is it enough that we don’t eat our co-workers?

British Journal of

Social Work, 42, 600-617. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcr091

Ferrell, J., & Crowley, S. L. (2021). Emotional support animals: A framework for clinical

decision-making.

Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 52(6), 560-568.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pro0000391

Friendly Dog Collars. (2022). Assistance dogs in Australia [website]. Available from

https://friendlydogcollars.com.au/blogs/news/the-truth-about-assistance-dogs-and-

service-dogs-in-australia

Hill, J. R., Ziviani, J., & Driscoll, C. (2020). “The connection just happens”: Therapists’

perspectives of canine-assisted occupational therapy for children on the autism

spectrum.

Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 67, 550-562.

https://DOI.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12680

International Society of Animal Assisted Therapy. (n.d.).

About [website]. Available from

https://isaat.org/about/

Koukourikos, K., Georgopoulou, A., Kourkouta, L., & Tsalogllidou, A. (2019). Benefits of animal

assisted therapy in mental health.

International Journal of Caring Sciences, 12(3), 1898-

1905.

V1 14-04-2022

Animal Assisted Therapy

Page 8 of 9

OFFICIAL

Page 8 of 9