FOI 23/24- 1400

DOCUMENT 10

Sensory-based therapy

The content of this document is OFFICIAL.

Please note:

The research and literature reviews collated by our TAB Research Team are not to be shared

external to the Branch. These are for internal TAB use only and are intended to assist our

advisors with their reasonable and necessary decision-making.

Delegates have access to a wide variety of comprehensive guidance material. If Delegates

require further information on access or planning matters, they are to call the TAPS line for

advice.

The Research Team are unable to ensure that the information listed below provides an

accurate & up-to-date snapshot of these matters

Research question: Is sensory integration, modulation, processing all talking about the

same thing? Any other important terms to define?

Who might benefit from sensory support?

What is the evidence sensory support reduces the need for RRP?

What is the evidence for other more general outcomes?

Who might implement/qualifications for sensory support?

Date: 29/09/2022

Requestor: Karyn Mueller

Endorsed by: Researcher: Stephanie Pritchard and Aaron Harrison

Cleared by: Stephanie Pritchard

Review date:

Page 103 of 125

link to page 1 link to page 1 link to page 2 link to page 3 link to page 3 link to page 4 link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 9 link to page 10 link to page 10

FOI 23/24- 1400

1. Contents

Sensory based interventions ...................................................................................................... 1

1.

Contents ....................................................................................................................... 2

2.

Summary ...................................................................................................................... 2

3.

Terminology .................................................................................................................. 3

3.1 Theoretical terminology ............................................................................................. 3

3.2 Types of sensory based interventions ....................................................................... 4

4.

Efficacy ......................................................................................................................... 7

4.1 Autism Spectrum Disorder ......................................................................................... 7

4.2 Mental Health ............................................................................................................ 9

4.3 Other conditions ...................................................................................................... 10

5.

References ................................................................................................................. 10

2. Summary

The terminology used in the literature on sensory disorder and sensory-based interventions

(SBIs) is inconsistent. The terms sensory integration, sensory processing and sensory

modulation are sometimes used interchangeably in the literature and sometimes given distinct

definitions. General features of these key terms can be described.

Researchers and clinicians have employed SBIs for a variety of conditions. Most of the

research available relates to interventions for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) or other

neurodevelopmental disorders such as intellectual disabilities or attention deficit/hyperactivity

disorder, schizophrenia or other mental health conditions such a bipolar, depression or

obsessive-compulsive disorder. There is also research relating to interventions for cerebral

palsy, Huntington’s disease and dementia.

There is some evidence that SBIs can contribute to a reduction in restrictive practice. The

evidence is predominantly in the domain of mental health and is predominantly related to

restrictive practice in a clinical or institutional setting. However, systematic reviews show

inconsistent results. Based on the evidence collected it is not possible to say with confidence

that SBIs reduce the use of restrictive practice. There are many factors which contribute to an

institution’s use of restrictive practice that are not addressed by the introduction of SBIs.

SBIs do likely have some positive effects. There is consistent evidence that SBIs reduce

distress of people with mental health conditions and lower quality evidence that distress is

reduced for people with Huntington’s disease and dementia. There is low to moderate quality

evidence of positive effect for young people with ASD relating to some core autistic

characteristics, life outcomes and cognitive, motor and social-emotional skills. There is weak

Page 104 of 125

FOI 23/24- 1400

evidence showing improvement in functional outcomes for children with intellectual disability

and development delay.

SBIs are usually implemented by an occupational therapist. However, other professionals can

be trained to implement SBIs including nurses, psychologists and speech therapists.

3. Terminology

The literature on sensory therapies is not well organised and key terminology is not used

consistently (Ouellet et al, 2021). However, rough definitions of the major concepts are

possible.

3.1 Theoretical terminology

Underlying theoretical terms are often used in different ways. Brown et al (2019) provide an

overview of the use of the terms

sensory integration,

sensory processing, sensory

modulation and

sensory perception, showing that despite considerable variation, these

terms

have also been used interchangeably in the literature. Based on their review, the

authors propose the following definition of sensory modulation:

Sensory modulation is considered a twofold process. It originates in the central nervous

system as the neurological ability to regulate and process sensory stimuli; this

subsequently offers the individual an opportunity to respond behaviourally to the

stimulus (Brown et al, 2019, p.521).

They characterise sensory modulation as a combined neurophysiological and behavioural

process within the larger category of sensory processing. Sensory processing also includes:

receiving, organisation, perception, interpretation, registration and discrimination. They

suggest sensory integration is the framework which encompasses the sensory processing sub-

processes and the disorders associated with those subtypes (Brown et al, 2019).

However, we should also recognise that the process of proposing consistent definitions of

these terms is largely revisionary considering the disagreement in the literature. For instance,

sensory integration can refer to a neurological process, a theory or a practice depending on

the researcher. Sensory processing might be used interchangeably with sensory integration

(Camarat et al, 2020; Brown et al, 2019). Sensory processing is more often used in the

literature related to autism, but sensory modulation is often used in the literature on mental

health to refer to the same types of interventions (Brown et al, 2019; Hitch et al, 2020).

There is inconsistency in the definitions of sensory disorders as well. Diagnosis is made based

on the presence of i) difficulties translating sensory information into appropriate behavioural

responses and; ii) a demonstrable effect on activities of daily living (Ouellet, 2021). There is

some controversy about whether sensory disorders are genuinely separate conditions or

whether they are collections of symptoms associated with other conditions. The category of

sensory disorders is not included in either the DSM-5 or the ICD-11 (American Psychiatric

Association, 2013; World Health Organisation, 2019).

Page 105 of 125

FOI 23/24- 1400

3.2 Types of sensory based interventions

Terms for therapeutic practices are also used in incompatible ways (Ouellet et al, 2021). In

particular, there is an ambiguity in the use of the term

sensory based interventions.

SBI can refer to a category of therapeutic techniques that include sensory integration therapy

(SIT), auditory integration therapy (AIT), use of multi-sensory environments (MSE) and other

techniques that target sensory processing difficulties. Preis and McKenna (2014) and

Whitehouse et al (2020) use SBI in this way.

However, SBI can also refer to specific practices that are distinguished from SIT, AIT or MSE.

Ouellet et al (2021), Basic et al (2021) and Wans Yunus et al (2015) draw the distinction

between SIT and SBI based on the number of therapeutic modalities or stimuli. SBI is used to

refer to techniques that use singular discrete stimuli to achieve the desired result (e.g.,

massage, a weighted vest). SIT on the other hand, uses multiple integrated stimuli and must

include more than one sensory modality (Parham et al, 2007).

McGil and Breen (2019) note a further complication: SBI-type strategies are emerging in the

context of positive behaviour support and multi-element behavioural interventions without

being labelled as SBIs.

There does seem to be agreement that SBIs are based on the theoretical premise that sensory

processing differences affect skil acquisition and behavioural development. By targeting

sensory processing, the interventions aim to improve behavioural problems, emotional

regulation, cognitive, language and social skil s (Whitehouse et al, 2020).

Discrete SBIs, SIT, MSE and AIT are considered in further detail below. There are other

therapeutic practices that can be included under the label SBI. Whitehouse et al also consider

environmental enrichment, sensory diet and the following:

alternative seating; blanket or “body sock”; brushing with a bristle or a feather; chewing

on a rubber tube; developmental speech and language training through music; family-

centered music therapy; joint compression or stretching; jumping or bouncing; music

therapy; playing with a water and sand sensory table; playing with specially textured

toys; Qigong Sensory Treatment (QST); Rhythm Intervention Sensorimotor Enrichment;

sensory enrichment; swinging or rocking stimulation; Thai traditional massage; Tomatis

Sound Therapy; and weighted vests (Whitehouse et al, 2020, p.70).

SBIs are usually implemented by occupational therapists, although speech therapists, nurses,

psychologists and other professionals can be trained to implement programs (McGil & Breen,

2019).

3.2.1 Sensory-based interventions

SBI provides sensory stimuli that are specific or discrete to address behavioural problems

causes by dif iculties in sensory processing (Wan Yunus, 2015; Ouellet et al, 2021). The

distinction between sensory-based and sensorimotor-based approaches is drawn differently in

the literature. Ouellet et al (2021) says that sensory-based approaches involve a stimulus of

Page 106 of 125

FOI 23/24- 1400

constant intensity, such as a weighted vest, whereas sensorimotor-based approaches include

the use of movements, allowing the person to control the quantity and intensity of stimulation.

In contrast, Wan Yunus et al (2015) distinguish between tactile (eg. massage, touch therapy,

brushing), proprioceptive (eg. weighted vests) and vestibular (eg. therapy ball, cushions, horse

riding) based interventions. Vestibular interventions involve patient movements and variation in

the constancy of intensity of stimulus was not noted as a distinguishing feature of different

techniques.

3.2.2 Sensory integration therapy

Sensory integration therapy (sometimes sensory processing therapy) is defined as any

intervention that targets someone’s “ability to integrate sensory information (visual, auditory,

tactile, proprioceptive, and vestibular) from their body and environment in order to respond

using organized and adaptive behaviour” (Steinbrenner et al, 2020, p.29). Steinbrenner et al

(2020) regard SIT as synonymous with Ayers Sensory Integration (Ayers). Whereas Omairi et

al (2022) treat Ayers as just one frequently used type of SIT.

Ayers can include equipment such as mats, swings, scooter boards and bolsters in

“individually tailored sensorimotor activities that are contextualized in play at the just-right

challenge to facilitate adaptive behaviours for participation in tasks and activities” (Omairi et al,

2022, p.4; Whitehouse et al, 2020). There are 10 core elements of Ayers:

• Provide sensory opportunities – intervention includes various sensory experiences

(tactile, proprioceptive, vestibular) involving more than one sensory modality.

• Provide just-right challenges – sensory challenges are neither too dif icult nor too

easy for the individual

• Collaborate on activity choice – the participant is an active contributor to the

intervention including choice of activity

• Guide self-organisation – participant is encouraged to initiate, plan and organise

their own activities

• Support optimal arousal – the context should allow the child to maintain their optimal

level of arousal

• Create play context – the context builds on the participants intrinsic motivation and

enjoyment of activities

• Maximise child’s success – activities are tailored so that the child can experience

success

• Ensure physical safety – activities are tailored so that the child is safe and properly

supervised

Page 107 of 125

FOI 23/24- 1400

• Arrange room for engagement – the environment is organised to motivate the

participant to participate in activities

• Foster therapeutic alliance – the participant is treated with respect and allowed to

have their own emotional reactions to experiences (Parham et al, 2007; Wans

Yunus et al, 2015; Whitehouse et al, 2020).

3.2.3 Multi-sensory environment

MSEs (also called comfort rooms, sensory rooms or Snoezelen rooms) are rooms that contain

equipment used to modify the environment primarily with the aim to create sensory

experiences. This includes equipment used to create lights, sounds, smells or proprioceptive

and tactile sensations. The goal of an MSE is to soothe or stimulate a person with sensory

needs (Unwin et al, 2022; Cameron et al, 2020).

Figure 1 Multi-sensory room

MSEs are often windowless or have covered walls. They commonly include:

(1) projection equipment to provide changing light colours and patterns, (2) sound

(music) equipment, (3) bubble tubes offering visual, audible and tactile stimulation, (4)

waterbed, (5) fibre optic lighting, (6) tactile objects, (7) user-controlled switching for

changing lighting and other equipment, (8) weighted blankets, (9) self-massagers, (10)

rocking chair(s), (11) exercise balls, and (12) squeeze balls (Cameron et al, 2020,

p.631).

Rooms might also include essential oils, scented candles, sweet or salty foods (Cameron et al,

2020). Participants can control aspects of the environment thereby reducing the

unpredictability or the environment and allowing the participant to regulate their own sensory

stimulation (Unwin et al, 2022).

Page 108 of 125

FOI 23/24- 1400

3.2.4 Auditory integration training

AIT aims to ‘re-educate’ the auditory processing system of the patient’s brain with 2 half hour

electronic music listening sessions over 10 days. This re-education process is intended to

target behaviour and learning problems in people with autism (Sinha et al, 2011).

Wans Yunus et al (2015) suggest auditory integration training (AIT) is a based on the same

theory of sensory integration as SIT. However, because SIT involves multiple sensory

modalities (Parham et al, 2007), AIT can only be considered a related therapy rather than a

kind of SIT. Other related techniques include Tomatis sound therapy and Samonas sound

therapy (Sinha et al, 2011).

3.2.5 Music therapy

Music therapy is considered a type of SBI by some (Whitehouse et al, 2020; Cheung et al,

2022) and not others (Steinbrenner et al, 2020). The mechanism by which music therapy is

supposed to work does involve active listening and auditory sensory experiences, though it

also includes social and cognitive processes (Geretsegger et al, 2014).

4. Efficacy

Researchers and clinicians have suggested that sensory based interventions could benefit

people with autism spectrum disorder, ADHD, developmental coordination disorder, cerebral

palsy, down syndrome, intellectual disability, dementia, depression, schizophrenia, mood

disorders, obsessive compulsive disorder (Wan Yunus et al, 2015; Sinha et al, 2011; Hitch et

al, 2020; Ouellet et al, 2021).

4.1 Autism Spectrum Disorder

Steinbrenner et al (2020) and Whitehouse et al (2020) consider sensory-based interventions in

their reviews of evidence-based treatments for young people with ASD.

Steinbrenner et al added Ayers to their 2020 review of evidence-based practices for children

and young people with autism spectrum disorder. They note evidence of effect on

communication, social skil s, cognitive and academic outcomes, adaptive coping skil s,

challenging behaviour, and motor skil s (Steinbrenner et al, 2020). However, Steinbrenner et al

did not assess the evidence for ef icacy in detail, but only show that Ayers meet their criteria

for being considered an evidence-based practice:

To be identified as evidence-based, a category of practice had to contain (a) two high

quality group design studies conducted by two different research groups, or (b) five high

quality single case design studies conducted by three different research groups and

involving a total of 20 participants across studies, or (c) a combination of one high

quality group design study and three high quality single case design studies with the

combination being conducted by two independent research groups (Steinbrenner et al,

2020, p.24).

Page 109 of 125

FOI 23/24- 1400

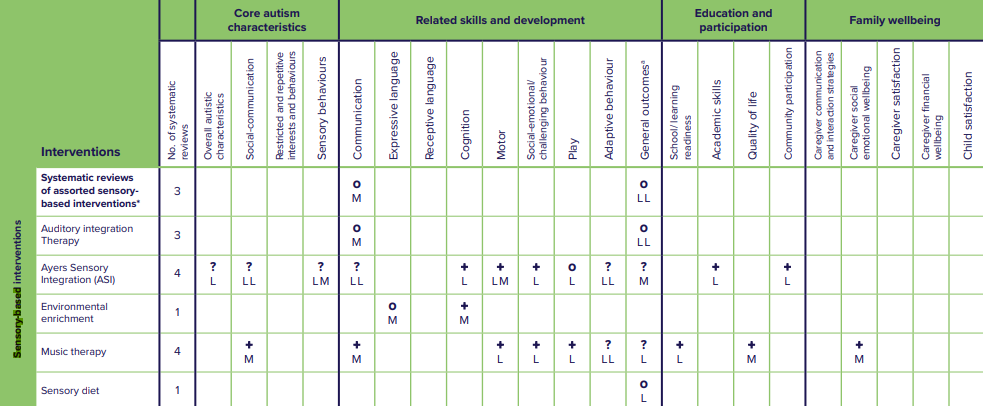

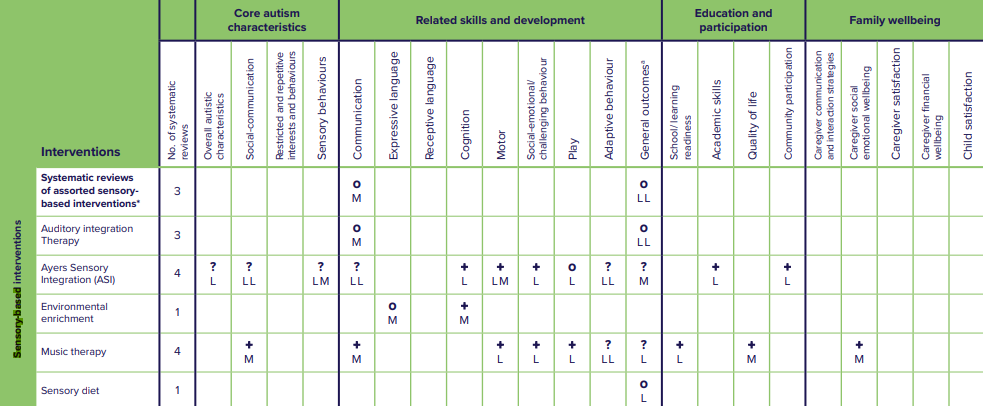

Whitehouse et al (2020) considered 9 systematic reviews. No evidence was found of a positive

effect for assorted SBIs, AIT or sensory diet. Environmental enrichment showed a positive

effect on motor skil s based on moderate quality evidence.

Ayers was considered in 4 reviews which showed low quality evidence of improvement to

cognition, motor skil s, challenging behaviours, academic skil s and community participation.

Reviewers also found moderate quality evidence of a benefit to motor skil s. Low or moderate

quality evidence showed inconsistent or null effect on autistic characteristics such as social-

communication and sensory behaviours, communication skil s, play, adaptive behaviour skil s,

and general outcomes. 1 review found evidence that SIT may contribute to increase in

stereotypical and problem behaviours (Whitehouse et al, 2020).

Music therapy demonstrated the most consistent positive effect. Reviewers found moderate

quality evidence showing positive effect on social-communication symptoms, communication

skills, and quality of life. Reviewers found low quality evidence showing positive effect on play,

motor skil s, challenging behaviours, and school readiness (Whitehouse et al, 2020).

Figure 2 Summary of evidence for sensory-based interventions. From Whitehouse et al, 2020, p.75

Wan Yunus et al (2015) argue that there is sufficient evidence that tactile stimulation (such as

massage therapy) positively affects challenging behaviours such that it can be included in

clinical practice. This contrasts with both Whitehouse et al (2020) and Steinbrenner et al

(2020) who note evidence that Ayers and music therapy can improve challenging behaviours,

but who do not recognise evidence that discrete tactile stimulation can improve challenging

behaviours.

Page 110 of 125

FOI 23/24- 1400

4.2 Mental Health

Sensory profiles of people with mental health conditions differ from the norm. Brown et al

(2020) found a general pattern of greater sensory sensitivity, sensation avoiding, and low

registration and less sensation seeking in a group of patients with either schizophrenia, high

risk for psychosis, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, posttraumatic stress and

obsessive-compulsive. Machingura et al (2022) confirmed higher rates of low registration and

sensory avoiding in a group of 41 people with schizophrenia.

SBIs are currently in use in mental health settings in Australia, including discrete SBIs and

MSEs. While the evidence base is stil emerging, existing studies consistently find an effect of

SBIs on distress. Multiple systematic reviews over the past 10 years have concluded that SBIs

are likely to contribute to a reduction in distress for patients with mental health issues in clinical

settings (Scanlon & Novak, 2015; Hitch et al, 2020; McGreevy & Boland, 2020; Ma et al, 2021;

Hain & Hallet, 2022). In a recent controlled trial, Machingura et al (2022) found a reduction in

distress for patients with schizophrenia when comparing pre- and post-test scores. However,

the effect was no longer statistically significant when compared with the control group.

SBIs are hypothesised to reduce the use of restrictive practice. State and national policies

aiming to reduce the use of restrictive practice are driving adoption of and research into SBIs

(Machingura et al, 2022; Baker et al, 2022; Baker et al, 2021; Hitch et al, 2020). The

suggestion is that if SBIs can reduce distress and level of arousal, then fewer episodes

requiring restrictive practice would occur. However, this assumption is questionable

considering the effect of workplace culture and institutional/state policy on rates of restrictive

practices (Scanlon & Novak, 2015). The evidence for an actual reduction in use of restrictive

practice is mixed.

Scanlon and Novak (2015) reviewed 17 papers and found that of the 9 studies reporting only

rates of restrictive practice use, all were using MSE type interventions. Of those studies 5

reported a reduction in rates of restraint or seclusion, 3 reported no change and 1 reported an

increase.

Other systematic reviews also show inconsistent evidence that MSEs used in clinical or

institutional settings can reduce restrictive practice. Haig and Hallett (2022) reviewed 6 studies

which reported rates or seclusion, restraint or violence. 4 of the 6 reported any positive results:

one out 6 studies found a reduction in seclusion episodes, 2 out of 6 found reductions in

restraint and 1 out of 6 found a reduction in aggression. One study also found an increase in

rates of seclusion. Haig and Hallett also note that all the studies reviewed had moderate to

high risk of bias.

Oostermeijer et al (2021) completed a rapid review including 14 studies on the effect of MSEs

on restrictive practices and found more positive results: 6 of the 14 studies found reduction in

restraint; 10 of the 14 found reduction in seclusion; 3 of the 14 reported no statistically

significant results; and 3 of the 14 reported an increase in restraint or seclusion.

Page 111 of 125

link to page 4 link to page 4

FOI 23/24- 1400

None of the systematic reviews were able to complete a meta-analysis. The inconsistency of

the evidence regarding MSEs effect on restrictive practice may relate to the unstructured and

heterogeneous nature of the intervention. There may be effective MSE-based practices or

protocols but existing studies have not identified them (Oostermeijer et al, 2021; Haig &

Hallett, 2022).

Most research on SBIs for people with mental health conditions occurs in a clinical or

institutional setting. Lack of research in community use of SBIs is a significant limitation of the

existing research (Hitch et al, 2020).

Hitch et al (2020) argue that despite minimal evidence, there is at least sufficient evidence to

support wider use in clinical settings due to minimal cost of implementation of many sensory

based interventions (for example, the discrete SBIs described i

n 3.2.1 Sensory-based

interventions).

4.3 Other conditions

There is some evidence that SBIs (especially MSEs, massage and music therapy) can

contribute to reduction in distress and agitation for people with dementia (Livingston et al,

2014; Pinto et al, 2020; Cheung et al, 2022).

Fisher et al (2014; 2017) show minimal evidence that SBI can reduce aggression in people

with Huntington’s disease.

Kantor et al (2022) found positive effects of Ayers on motor skil s of children with cerebral

palsy. However, better quality evidence is required to draw reliable conclusions.

A 2015 meta-analysis found only weak evidence for the efficacy of SIT in improving functional

outcomes for children with intellectual disability and development delay (Leong et al, 2015).

Subsequent studies have shown that SIT can assist children with developmental delay when

combined with a more comprehensive early intervention program (Wang et al, 2020).

5. References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental

disorders (5th ed.).

https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Baker, J., Berzins, K., Canvin, K., Benson, I., Kel ar, I., Wright, J., Lopez, R. R., Duxbury, J.,

Kendall, T., & Stewart, D. (2021). Non-pharmacological interventions to reduce

restrictive practices in adult mental health inpatient settings: the COMPARE systematic

mapping review.

Health Services and Delivery Research,

9(5), 1–184.

https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr09050

Baker, J., Berzins, K., Canvin, K., Kendal, S., Branthonne-Foster, S., Wright, J., McDougal , T.,

Goldson, B., Kellar, I., & Duxbury, J. (2022). Components of interventions to reduce

restrictive practices with children and young people in institutional settings: the Contrast

Page 112 of 125

FOI 23/24- 1400

systematic mapping review.

Health and Social Care Delivery Research,

10(8), 1–180.

https://doi.org/10.3310/yvkt5692

Basic, A., Macesic Petrovic, D., Pantovic, L., Zdravkovic Parezanovic, R., Gajic, A., Arsic, B.,

Nikolic, J. (2021). Sensory integration and activities that promote sensory integration in

children with autism spectrum disorders.

Journal Human Research in Rehabilitation,

11(1), 28–38.

https://doi.org/10.21554/hrr.042104

Brown, A., Tse, T., & Fortune, T. (2019). Defining sensory modulation: A review of the concept

and a contemporary definition for application by occupational therapists.

Scandinavian

Journal of Occupational Therapy,

26(7), 515–523.

https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2018.1509370

Brown, C., Karim, R., & Steuter, M. (2020). Retrospective analysis of studies examining

sensory processing preferences in people with a psychiatric condition.

The American

Journal of Occupational Therapy: Official Publication of the American Occupational

Therapy Association,

74(4), 7404205130p1-7404205130p11.

https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.038463

Cameron, A., Burns, P., Garner, A., Lau, S., Dixon, R., Pascoe, C., & Szafraniec, M. (2020).

Making sense of multi-sensory environments: A scoping review.

International Journal of

Disability, Development, and Education,

67(6), 630–656.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912x.2019.1634247

Cheung, D. S. K., Wang, S. S., Li, Y., Ho, K. H. M., Kwok, R. K. H., Mo, S. H., & Bressington,

D. (2022). Sensory-based interventions for the immediate de-escalation of agitation in

people with dementia: A systematic review.

Aging & Mental Health, 1–12.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2022.2116404

Fisher, C. A., Sewell, K., Brown, A., & Churchyard, A. (2014). Aggression in Huntington’s

disease: a systematic review of rates of aggression and treatment methods.

Journal of

Huntington’s Disease,

3(4), 319–332.

https:/ doi.org/10.3233/JHD-140127

Fisher, C. A., & Brown, A. (2017). Sensory modulation intervention and behaviour support

modification for the treatment of severe aggression in Huntington’s disease. A single

case experimental design.

Neuropsychological Rehabilitation,

27(6), 891–903.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2015.1091779

Geretsegger, M., Elefant, C., Mössler, K. A., & Gold, C. (2014). Music therapy for people with

autism spectrum disorder.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews,

2016(6),

CD004381.

https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004381.pub3

Haig, S., & Hallett, N. (2022). Use of sensory rooms in adult psychiatric inpatient settings: A

systematic review and narrative synthesis.

International Journal of Mental Health

Nursing. https:/ doi.org/10.1111/inm.13065

Hitch D, Wilson C, Hillman A. (2020) Sensory modulation in mental health practice. Mental

Health Practice.

https:/ doi.org/10.7748/mhp.2020.e1422

Page 113 of 125

FOI 23/24- 1400

Kantor, J., Hlaváčková, L., Du, J., Dvořáková, P., Svobodová, Z., Karasová, K., & Kantorová,

L. (2022). The effects of Ayres sensory integration and related sensory based

interventions in children with cerebral palsy: A scoping review.

Children (Basel,

Switzerland),

9(4), 483.

https://doi.org/10.3390/children9040483

Leong, H. M., Carter, M., & Stephenson, J. R. (2015). Meta-analysis of research on sensory

integration therapy for individuals with developmental and learning disabilities.

Journal

of Developmental and Physical Disabilities,

27(2), 183–206.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-014-9408-y

Livingston, G., Kelly, L., Lewis-Holmes, E., Baio, G., Morris, S., Patel, N., Omar, R. Z., Katona,

C., & Cooper, C. (2014). A systematic review of the clinical effectiveness and cost-

effectiveness of sensory, psychological and behavioural interventions for managing

agitation in older adults with dementia.

Health Technology Assessment (Winchester,

England),

18(39), 1–226, v–vi.

https://doi.org/10.3310/hta18390

Ma, D., Su, J., Wang, H., Zhao, Y., Li, H., Li, Y., Zhang, X., Qi, Y., & Sun, J. (2021). Sensory-

based approaches in psychiatric care: A systematic mixed-methods review.

Journal of

Advanced Nursing,

77(10), 3991–4004.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14884

Machingura, T., Shum, D., Lloyd, C., Murphy, K., Rathbone, E., & Green, H. (2022).

Effectiveness of sensory modulation for people with schizophrenia: A multisite

quantitative prospective cohort study.

Australian Occupational Therapy Journal,

69(4),

424–435.

https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12803

McGil , C., & Breen, C. J. (2020). Can sensory integration have a role in multi‐element

behavioural intervention? An evaluation of factors associated with the management of

challenging behaviour in community adult learning disability services.

British Journal of

Learning Disabilities,

48(2), 142–153.

https:/ doi.org/10.1111/bld.12308

McGreevy, S., & Boland, P. (2020). Sensory-based interventions with adult and adolescent

trauma survivors: An integrative review of the occupational therapy literature.

Irish

Journal of Occupational Therapy,

48(1), 31–54.

https://doi.org/10.1108/ijot-10-2019-

0014

Omairi, C., Mail oux, Z., Antoniuk, S. A., & Schaaf, R. (2022). Occupational therapy using

Ayres Sensory Integration®: A randomized controlled trial in Brazil.

The American

Journal of Occupational Therapy: Official Publication of the American Occupational

Therapy Association,

76(4).

https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2022.048249

Oostermeijer, S., Brasier, C., Harvey, C., Hamilton, B., Roper, C., Martel, A., Fletcher, J., &

Brophy, L. (2021). Design features that reduce the use of seclusion and restraint in

mental health facilities: a rapid systematic review.

BMJ Open,

11(7), e046647.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046647

Ouellet, B., Carreau, E., Dion, V., Rouat, A., Tremblay, E., & Voisin, J. I. A. (2021). Efficacy of

sensory interventions on school participation of children with sensory disorders: A

Page 114 of 125

FOI 23/24- 1400

systematic review.

American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine,

15(1), 75–83.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827618784274

Parham, L. D., Cohn, E. S., Spitzer, S., Koomar, J. A., Mil er, L. J., Burke, J. P., Brett-Green,

B., Mail oux, Z., May-Benson, T. A., Roley, S. S., Schaaf, R. C., Schoen, S. A., &

Summers, C. A. (2007). Fidelity in sensory integration intervention research.

The

American Journal of Occupational Therapy: Official Publication of the American

Occupational Therapy Association,

61(2), 216–227.

https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.61.2.216

Pinto, J. O., Dores, A. R., Geraldo, A., Peixoto, B., & Barbosa, F. (2020). Sensory stimulation

programs in dementia: a systematic review of methods and effectiveness.

Expert

Review of Neurotherapeutics,

20(12), 1229–1247.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14737175.2020.1825942

Preis, J., & McKenna, M. (2014). The effects of sensory integration therapy on verbal

expression and engagement in children with autism.

International Journal of Therapy

and Rehabilitation,

21(10), 476–486.

https://doi.org/10.12968/ijtr.2014.21.10.476

Scanlan, J. N., & Novak, T. (2015). Sensory approaches in mental health: A scoping review.

Australian Occupational Therapy Journal,

62(5), 277–285.

https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-

1630.12224

Sinha, Y., Silove, N., Hayen, A., & Wil iams, K. (2011). Auditory integration training and other

sound therapies for autism spectrum disorders (ASD).

Cochrane Database of

Systematic Reviews,

12, CD003681.

https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003681.pub3

Steinbrenner, J. R., Hume, K., Odom, S. L., Morin, K. L., Nowel , S. W., Tomaszewski, B.,

Szendrey, S., McIntyre, N. S., Yücesoy-Özkan, S., & Savage, M. N. (2020). Evidence-

based practices for children, youth, and young adults with Autism. The University of

North Carolina at Chapel Hil , Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute,

National Clearinghouse on Autism Evidence and Practice Review Team.

Unwin, K. L., Powell, G., & Jones, C. R. (2022). The use of Multi-Sensory Environments with

autistic children: Exploring the effect of having control of sensory changes.

Autism: The

International Journal of Research and Practice,

26(6), 1379–1394.

https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613211050176

Wan Yunus, F., Liu, K. P. Y., Bissett, M., & Penkala, S. (2015). Sensory-based intervention for

children with behavioral problems: A systematic review.

Journal of Autism and

Developmental Disorders,

45(11), 3565–3579.

https:/ doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-

2503-9

Wang, L.-J., Hsieh, H.-Y., Chen, L.-Y., Ko, K.-L., Liu, H.-H., Chou, W.-J., Chou, M.-C., & Tsai,

C.-S. (2020). Adjunctive sensory integration therapy for children with developmental

disabilities in a family-based early intervention program.

Taiwanese Journal of

Psychiatry,

34(3), 121.

https://doi.org/10.4103/tpsy.tpsy 26 20

Page 115 of 125

FOI 23/24- 1400

Whitehouse, A., Varcin, K., Waddington, H., Sulek, R., Bent, C., Ashburner, J., Eapen, V.,

Goodall, E., Hudry, K., Roberts, J., Silove, N., Trembath, D. (2020). Interventions for

children on the autism spectrum: A synthesis of research evidence. Autism CRC,

Brisbane

World Health Organization. (2019). ICD-11: International classification of diseases (11th

revision).

https://icd.who.int/

Page 116 of 125