FOI 24/25- 0013

DOCUMENT 11

Research – Recreational Supports: Barriers to participation

Statistics and research to support the development of an NDIS funding

position or at least an advice position on Recreational Supports.

TAB Advisors are seeking evidence base around Recreational Supports to

understand how to apply the legislation consistently for our participants.

Is there any research on the benefits of solo recreational activities (eg. knitting,

Brief

crocheting, exercising)

What is the typical number of recreational activities engaged by the average

Australian (both adult and child)

There is some research done into participation of people with a disability in

recreation, what does this tell us about types of recreation and the barriers to

participation (i.e. is AT or lack of it a barrier?)"

Date

November 13, 2020

s22(1)(a)(ii) -

Requester(s)

Tiffany

(Senior Technical Advisor – TAB)

Jane s22(1)(a)(ii)

- irre (As sistant Director – TAB)

Researcher

Craig s22(1)(a)(ii) - i (Tac tical Research Advisor – TAB/AAT)

Cleared

Jane s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelev (R esearch Team Leader)

Please note:

The research and literature reviews col ated by our TAB Research Team are not to be shared external to the Branch. These

are for internal TAB use only and are intended to assist our advisors with their reasonable and necessary decision-making.

Delegates have access to a wide variety of comprehensive guidance material. If Delegates require further information on

access or planning matters they are to call the TAPS line for advice.

The Research Team are unable to ensure that the information listed below provides an accurate & up-to-date snapshot of

these matters.

Contents

Summary ................................................................................................................................................. 2

Benefits of solo recreational activities .................................................................................................... 3

Overview ............................................................................................................................................. 3

Adults with chronic health conditions ................................................................................................ 5

Adults with Psychological Distress ...................................................................................................... 6

Recreational activities engaged by the average Australian .................................................................... 6

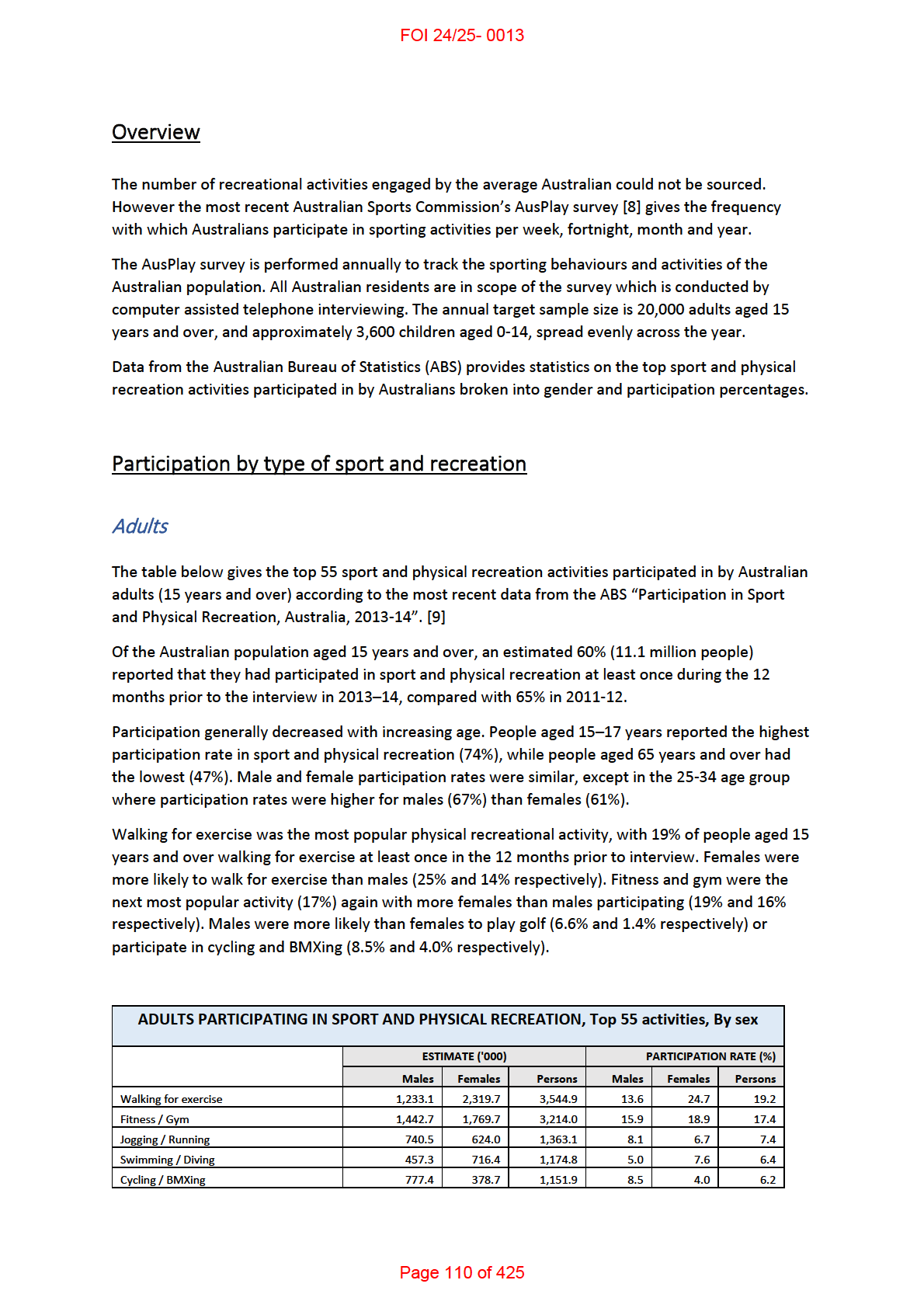

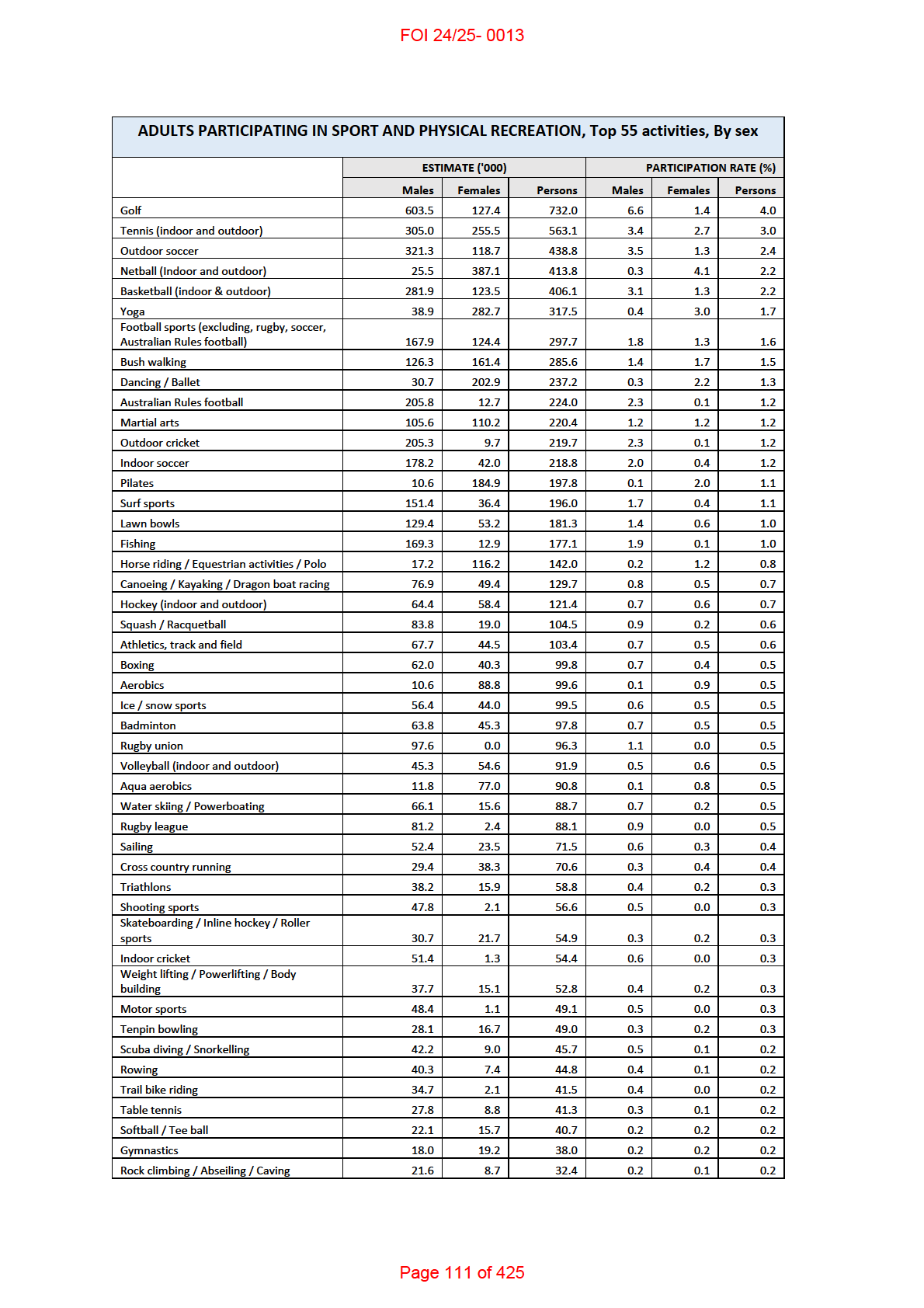

Overview ............................................................................................................................................. 7

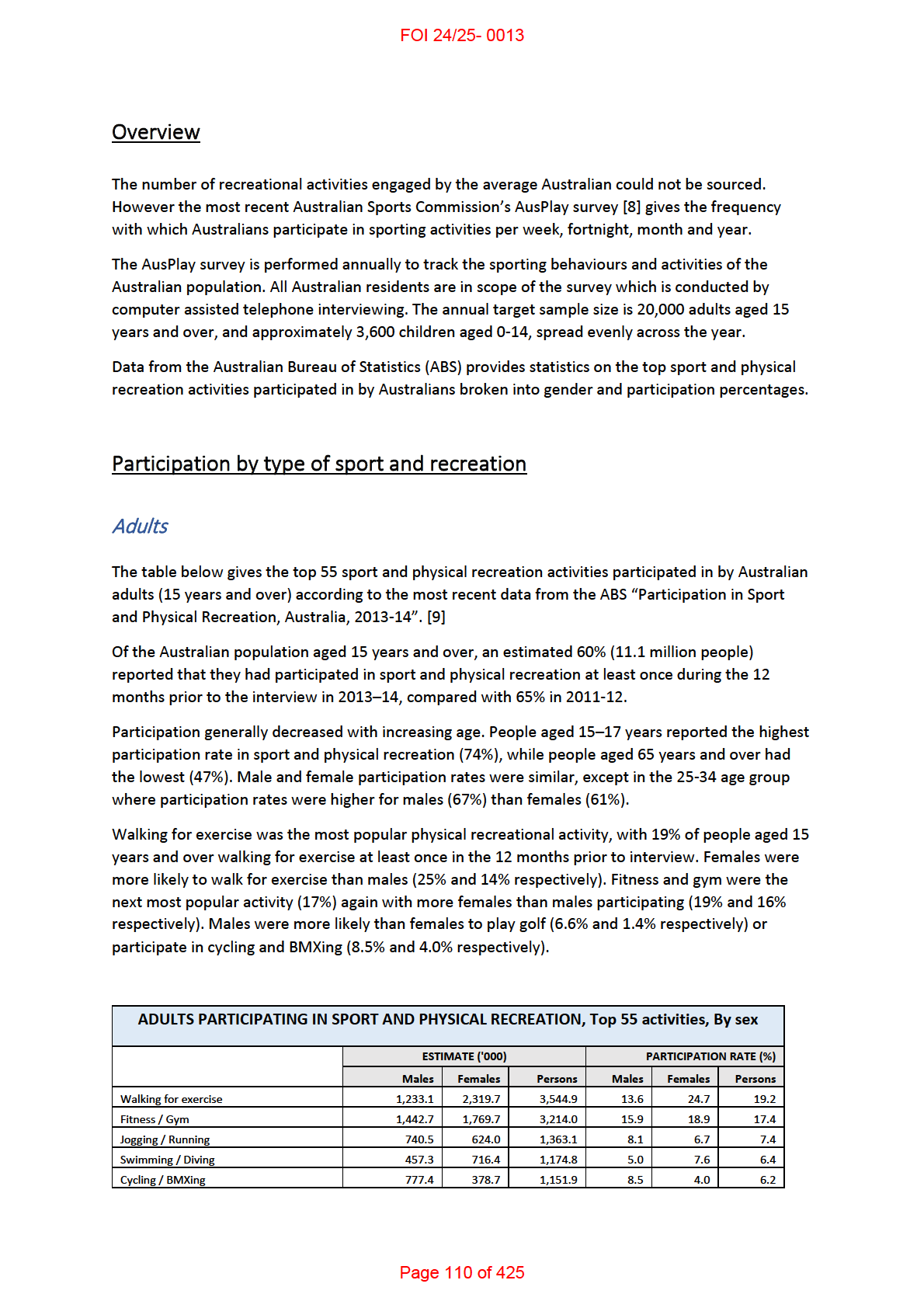

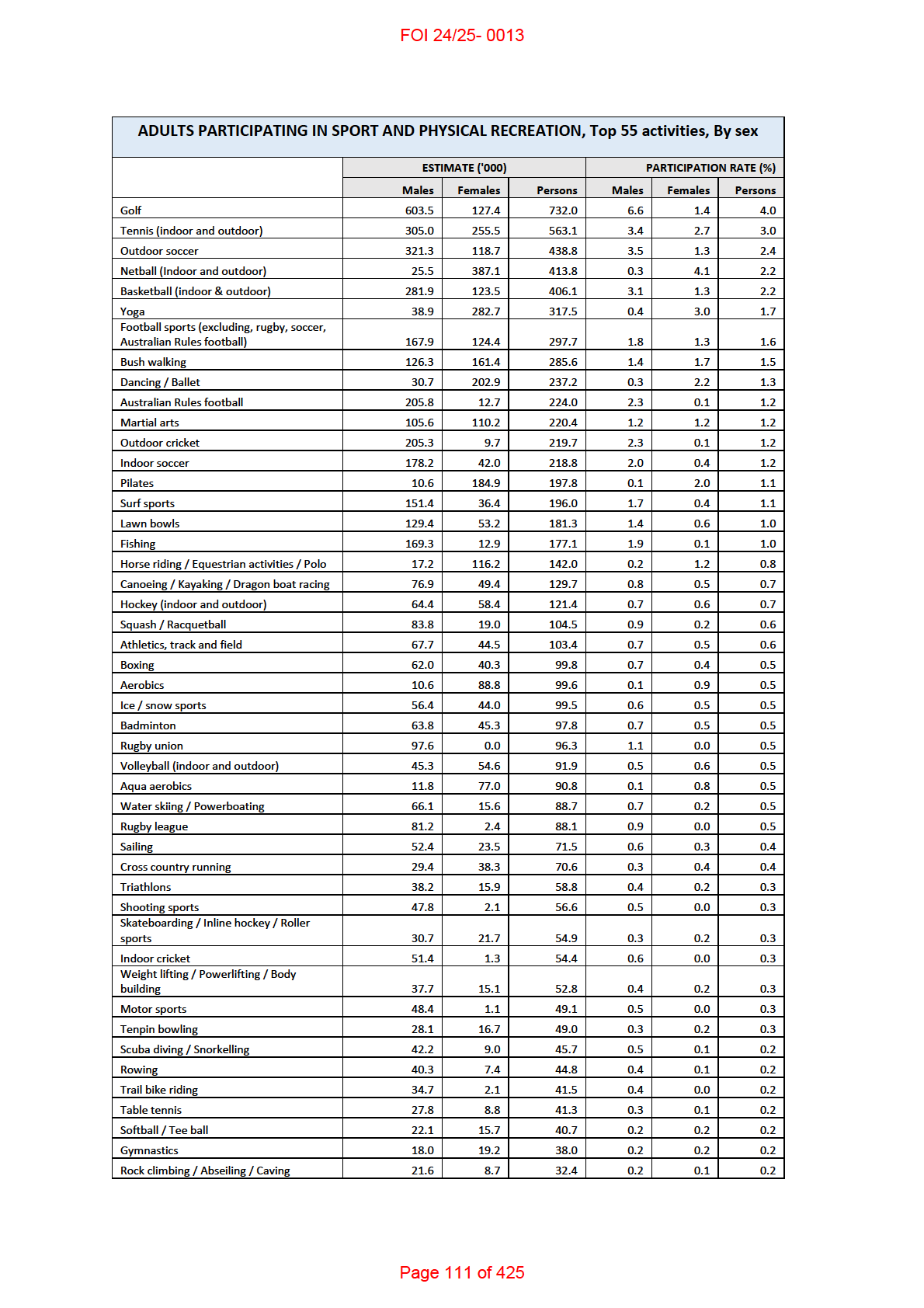

Participation by type of sport and recreation ..................................................................................... 7

Adults .............................................................................................................................................. 7

Page 104 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

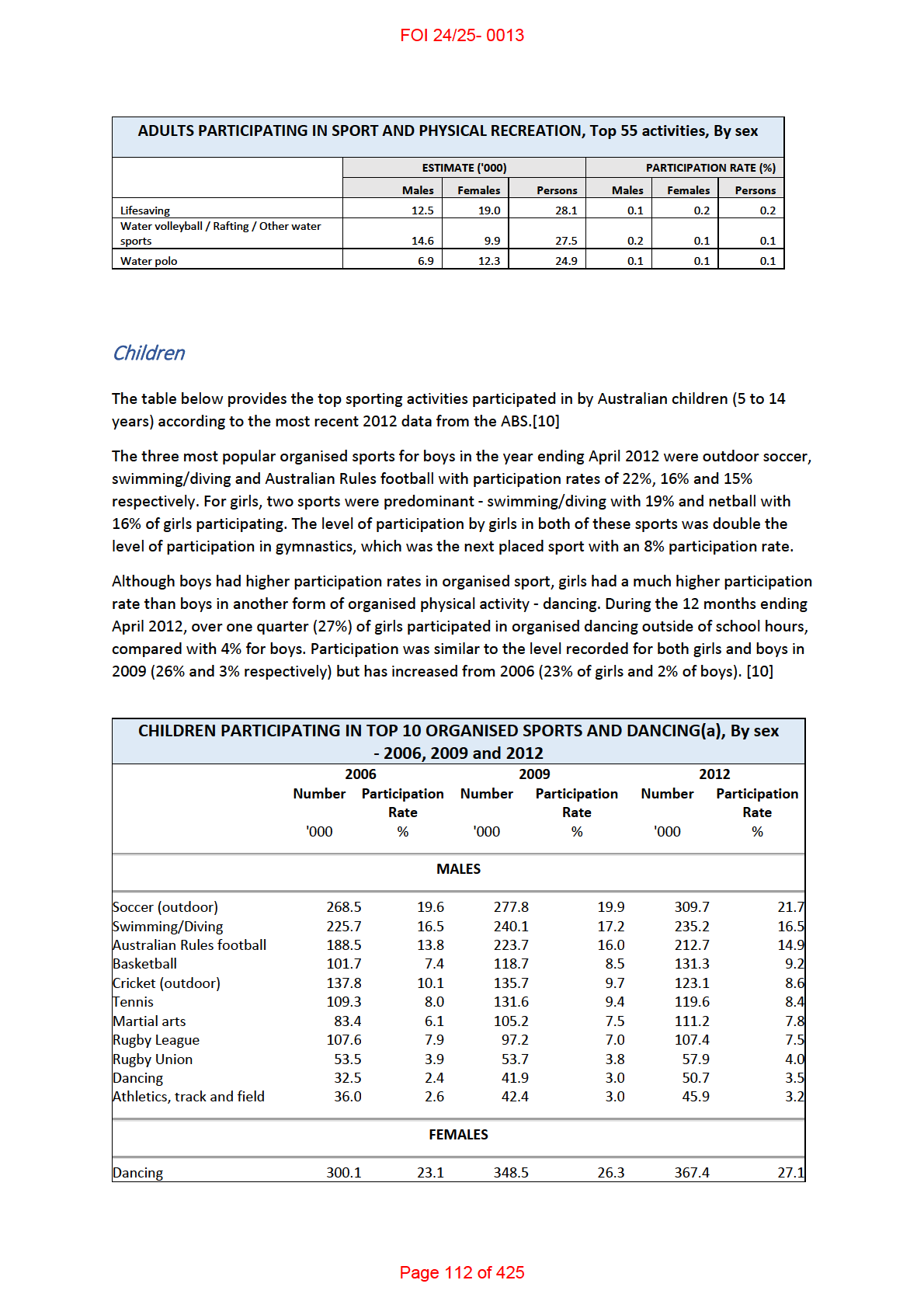

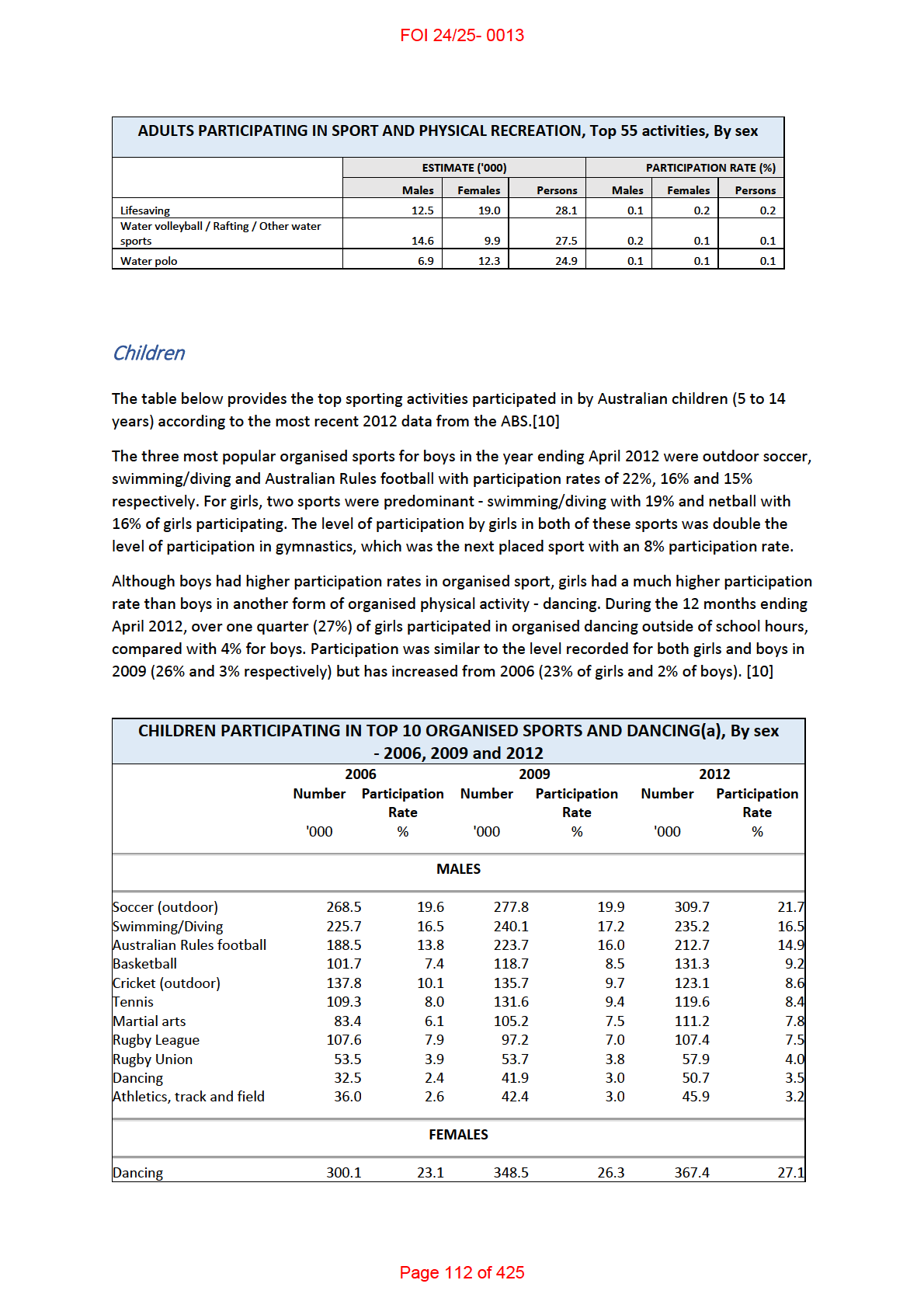

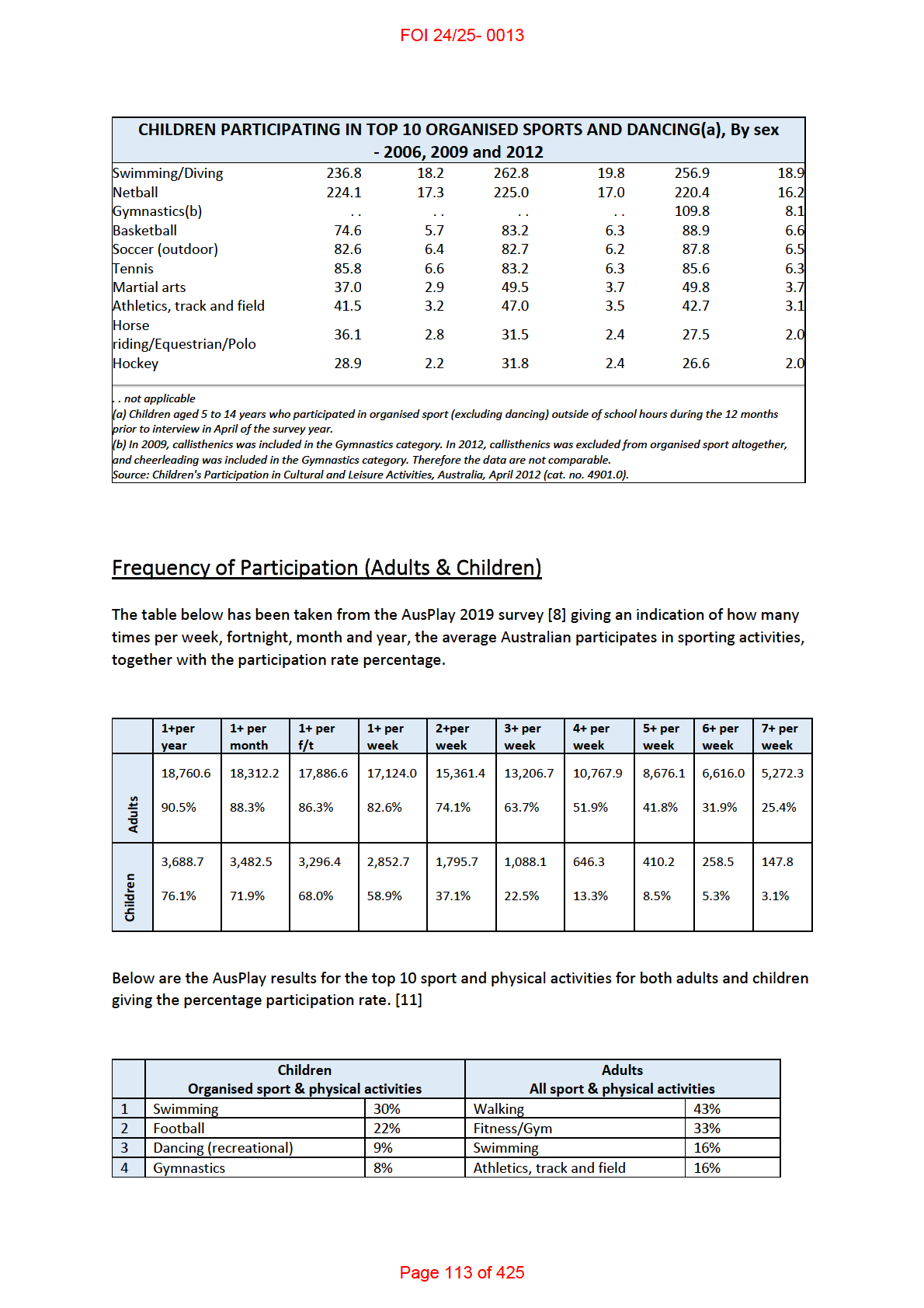

Children ........................................................................................................................................... 9

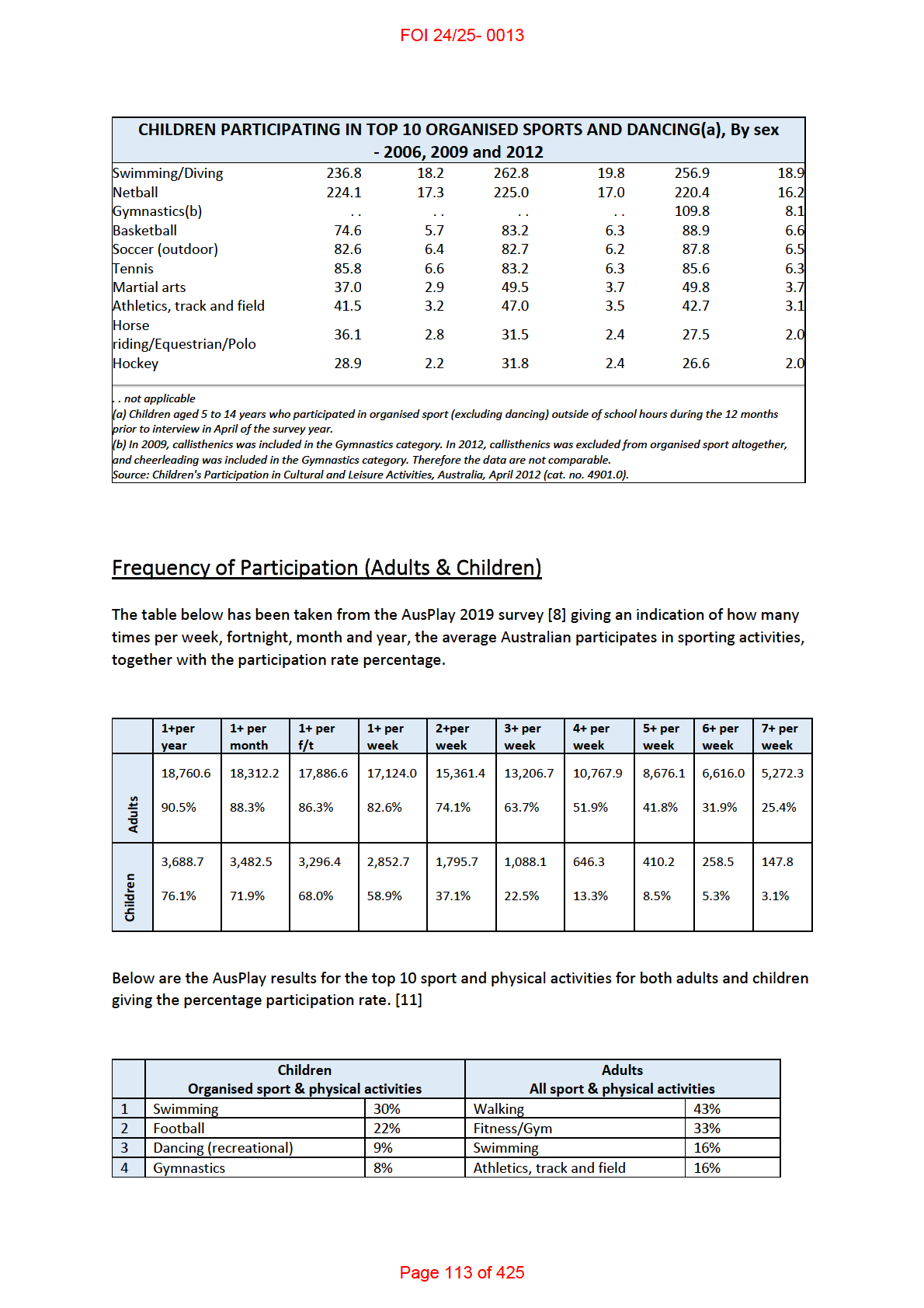

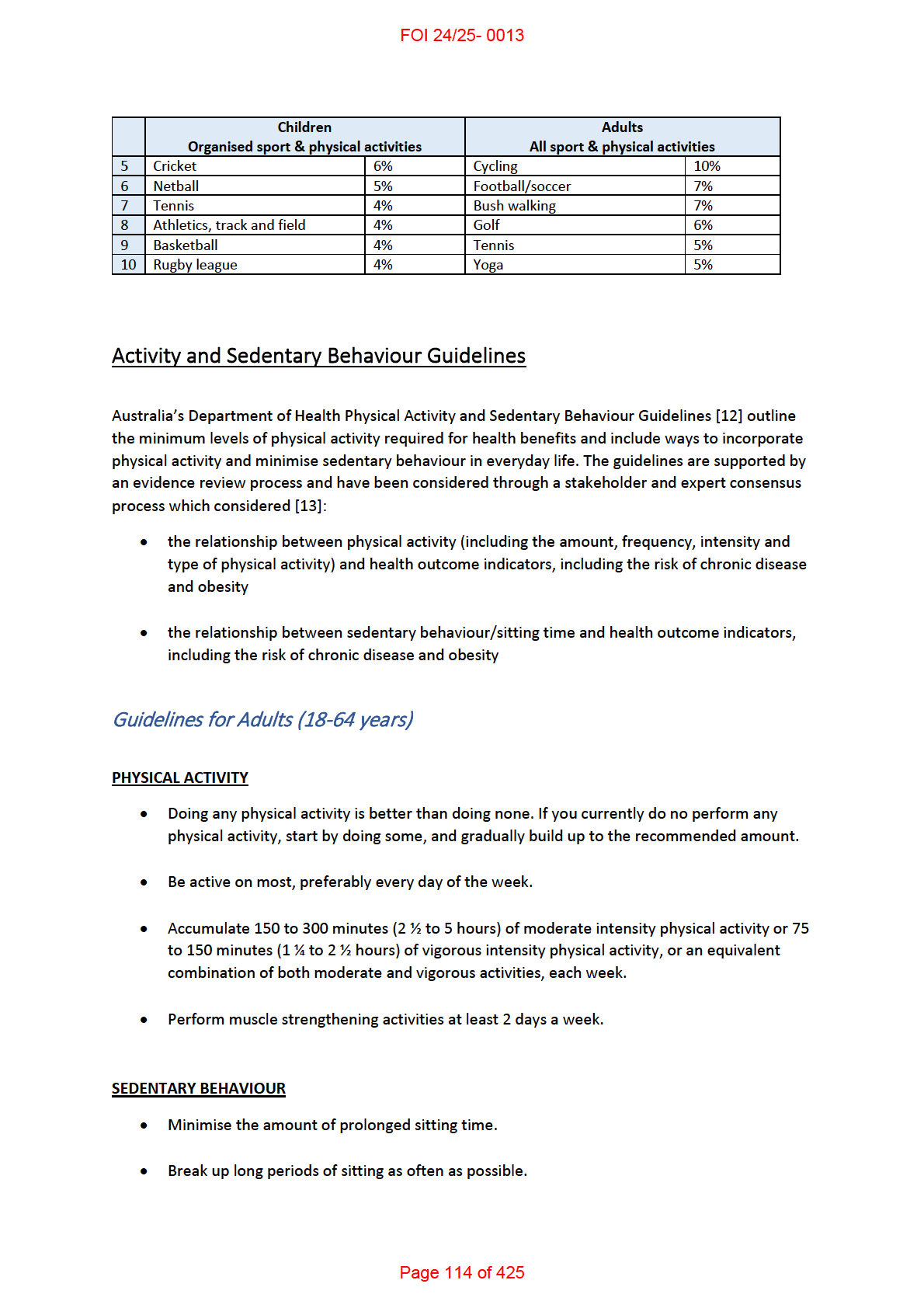

Frequency of Participation (Adults & Children) ................................................................................ 10

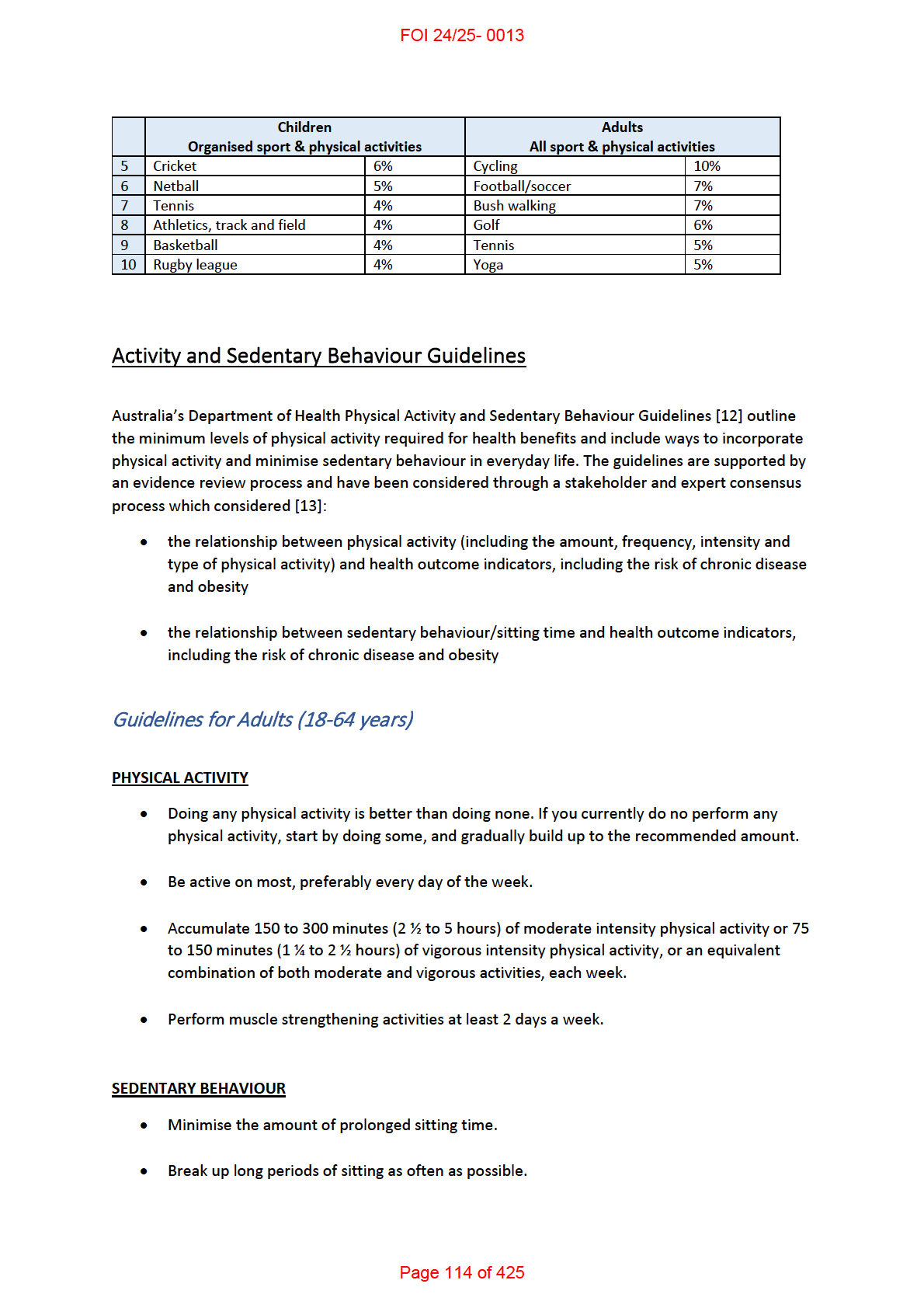

Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines ................................................................................... 11

Guidelines for Adults (18-64 years) .............................................................................................. 11

Guidelines for Children and Young people (5-7 years) ................................................................. 12

People with a disability (Types of recreational participation and barriers to participation) ................ 12

Overview ........................................................................................................................................... 12

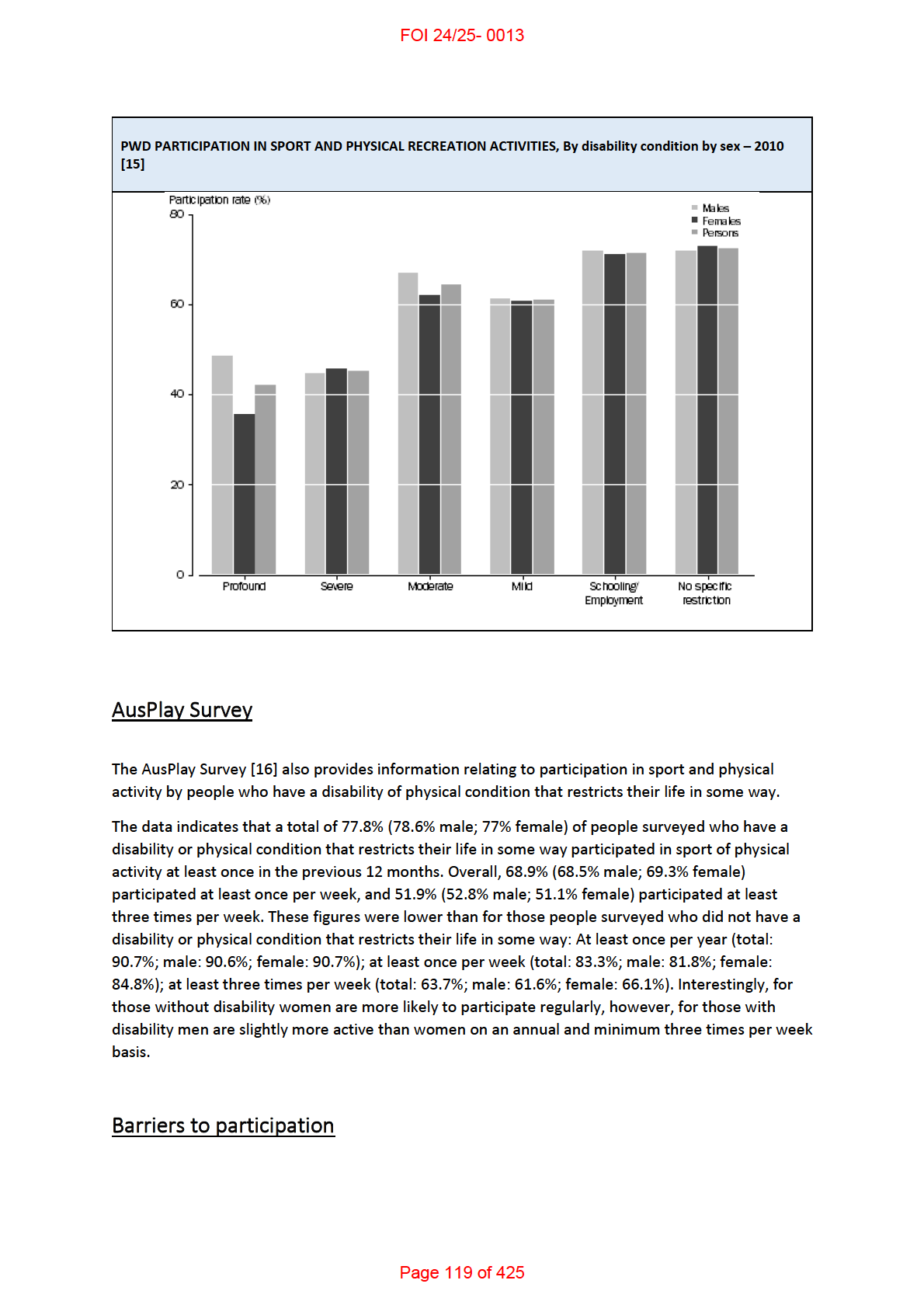

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Data ........................................................................................ 13

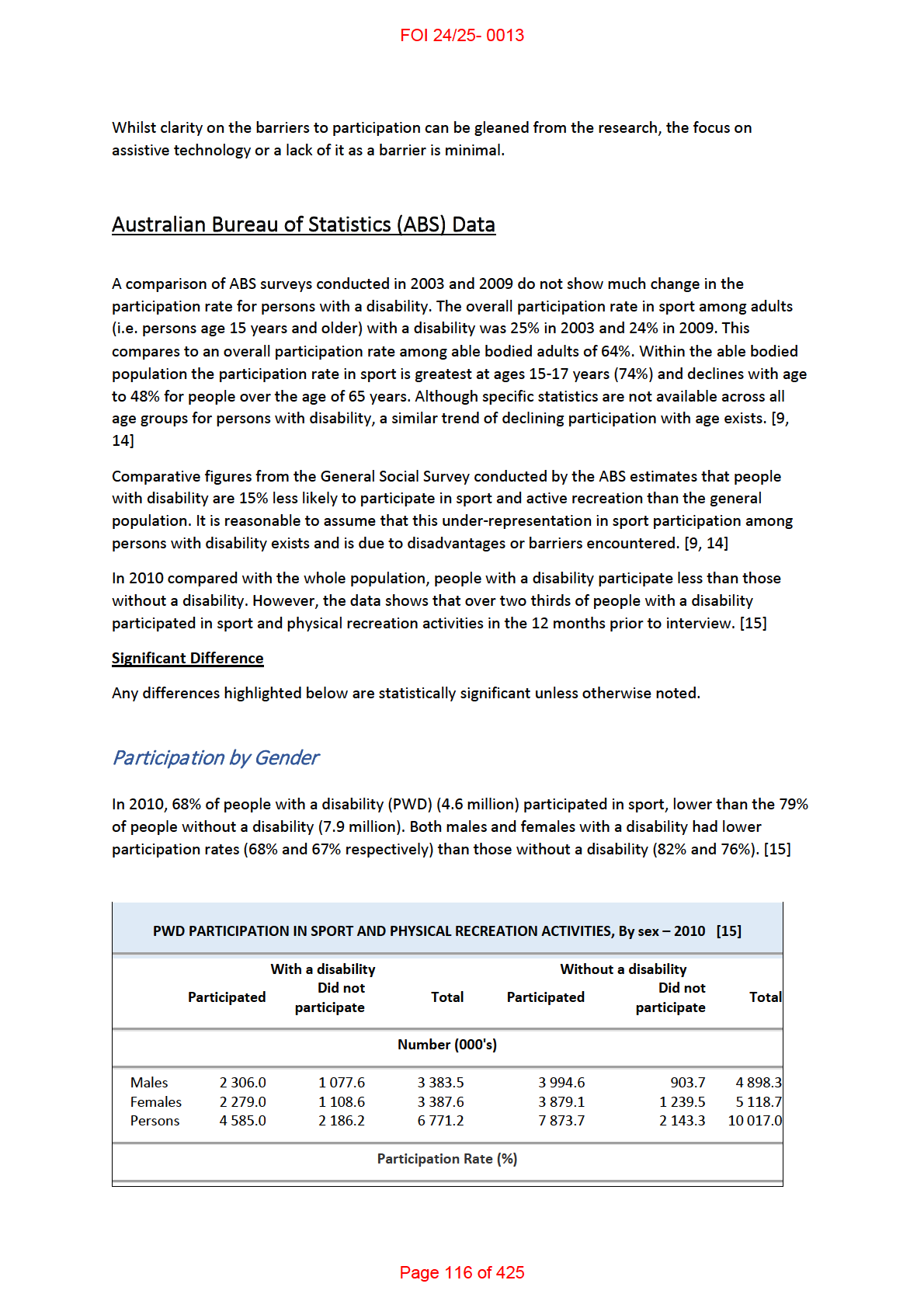

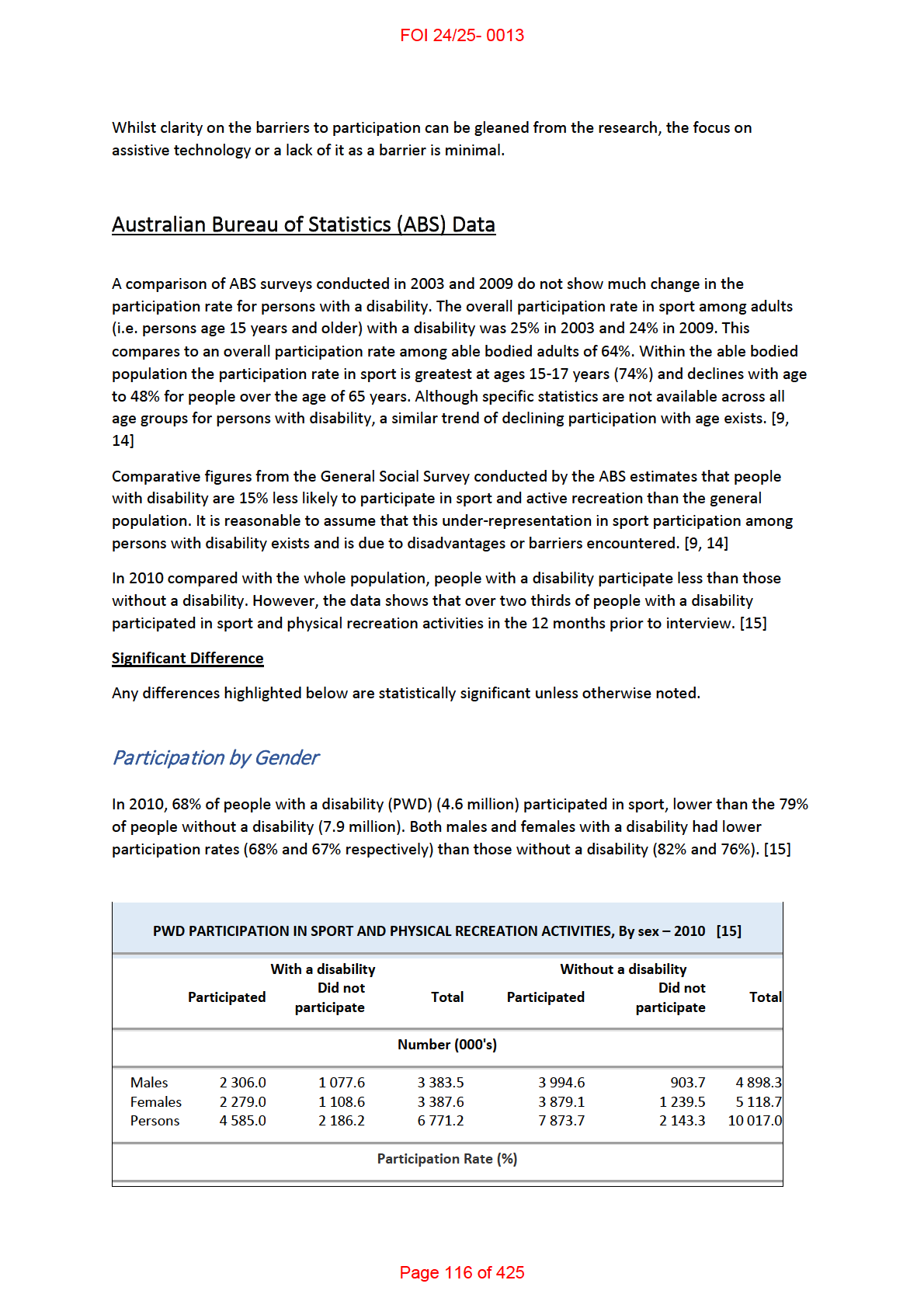

Participation by Gender ................................................................................................................ 13

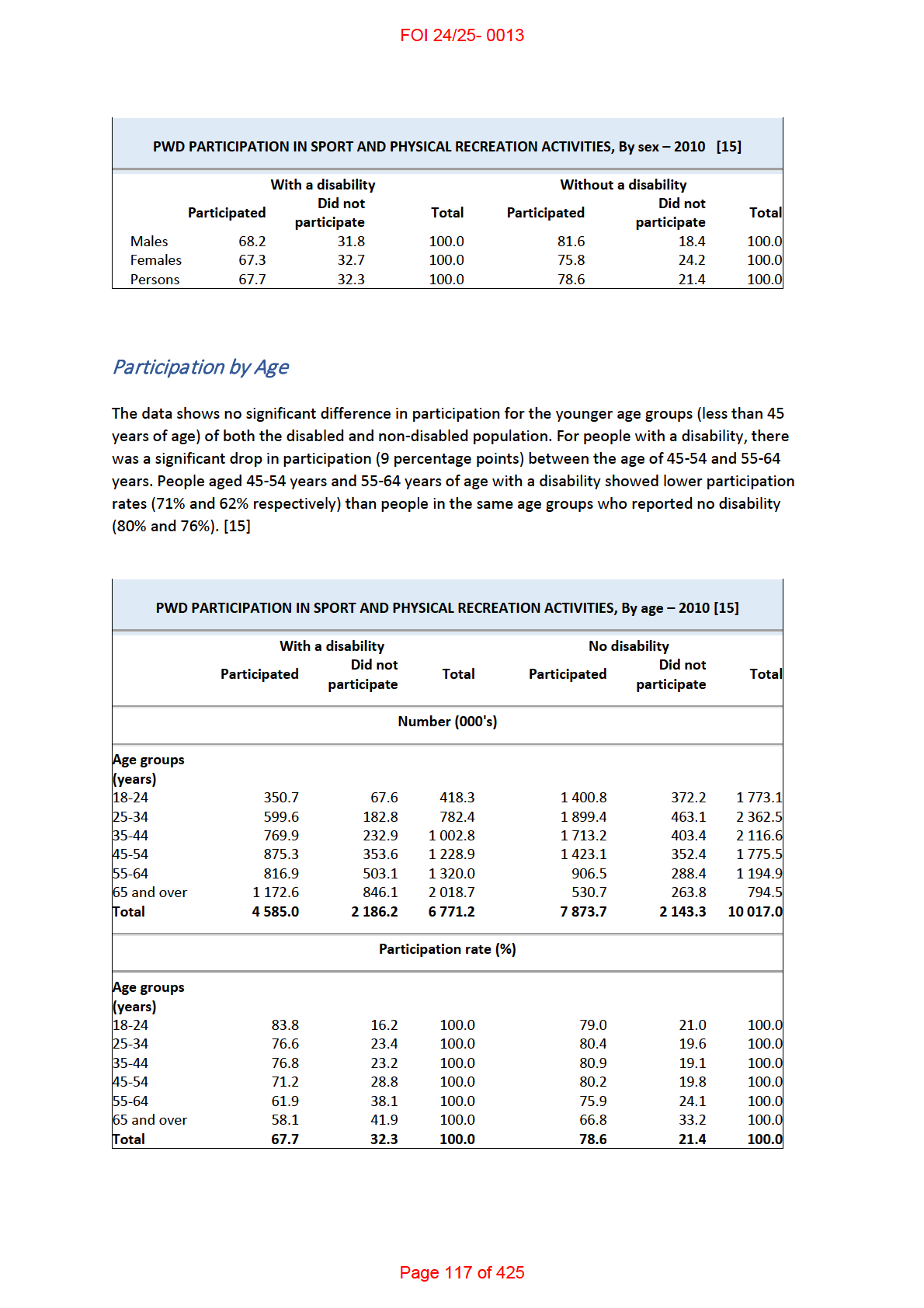

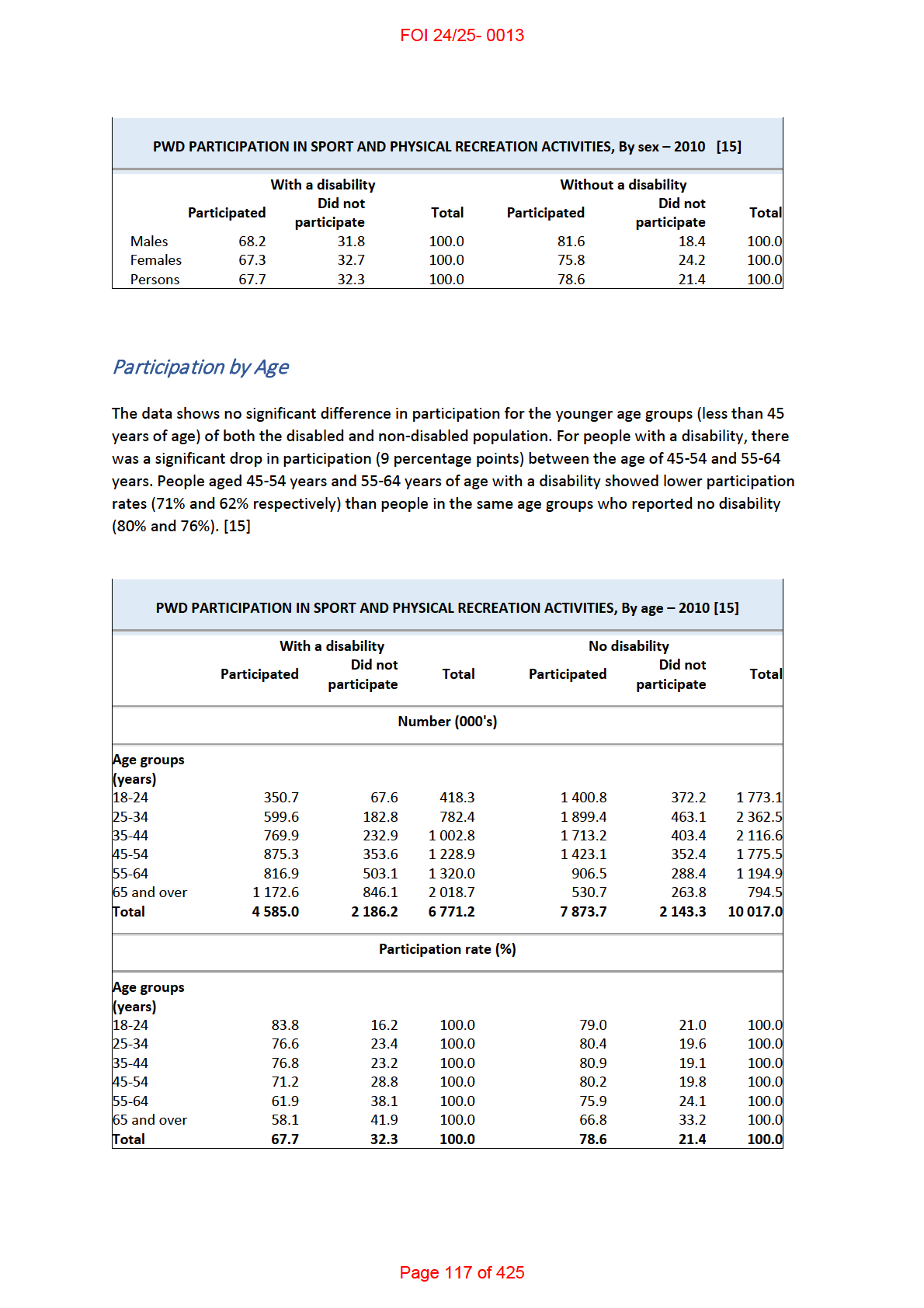

Participation by Age ...................................................................................................................... 14

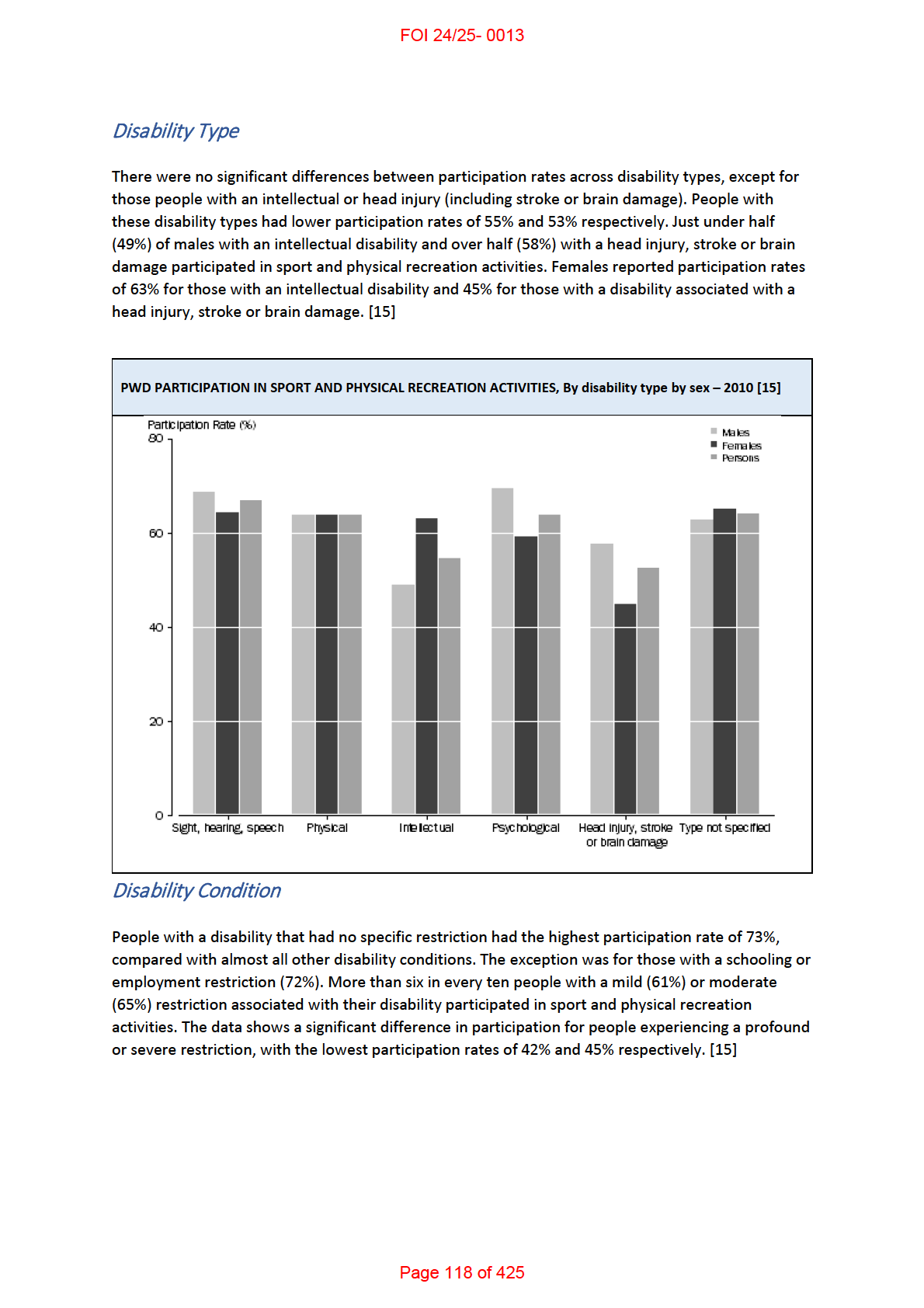

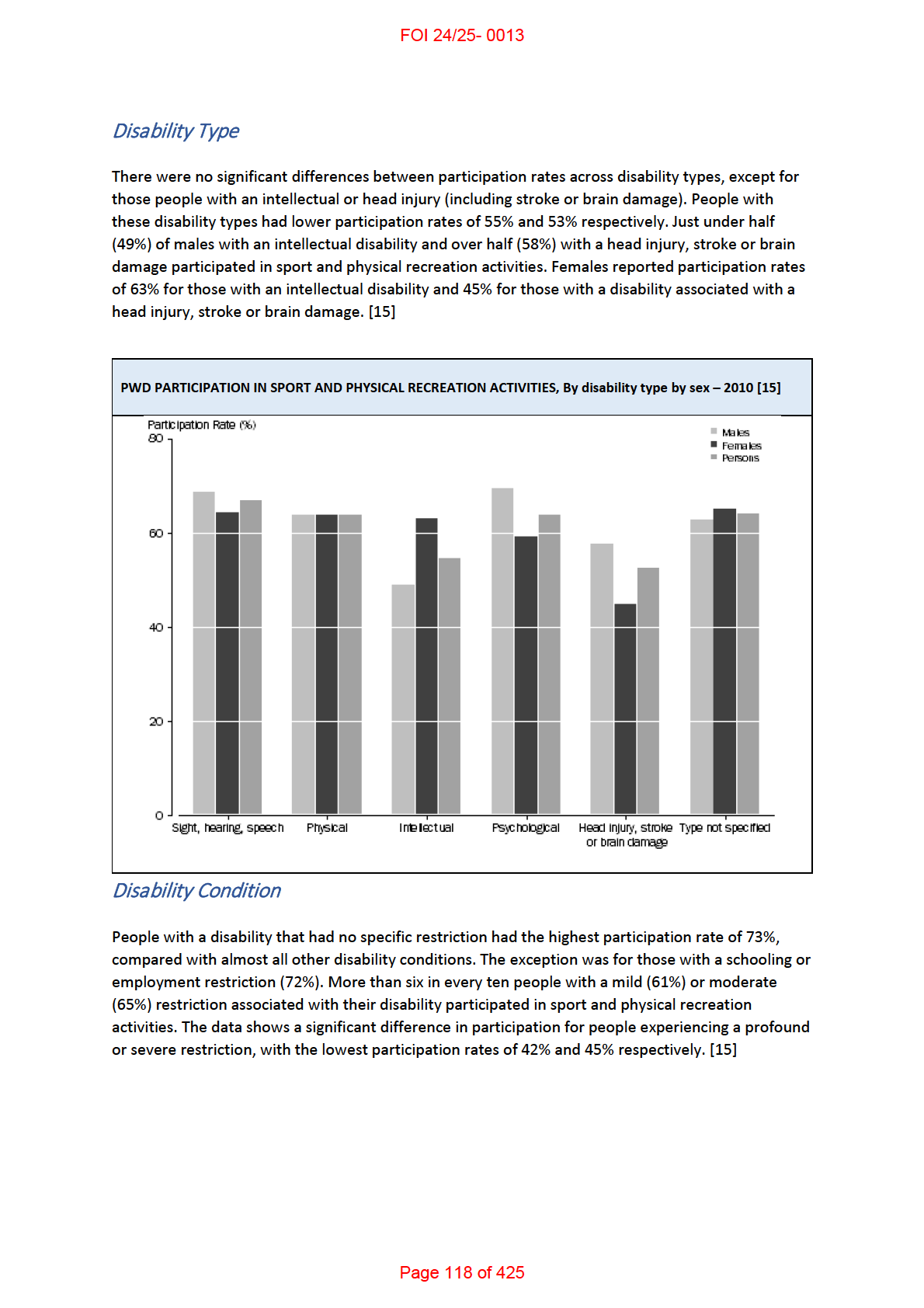

Disability Type ............................................................................................................................... 15

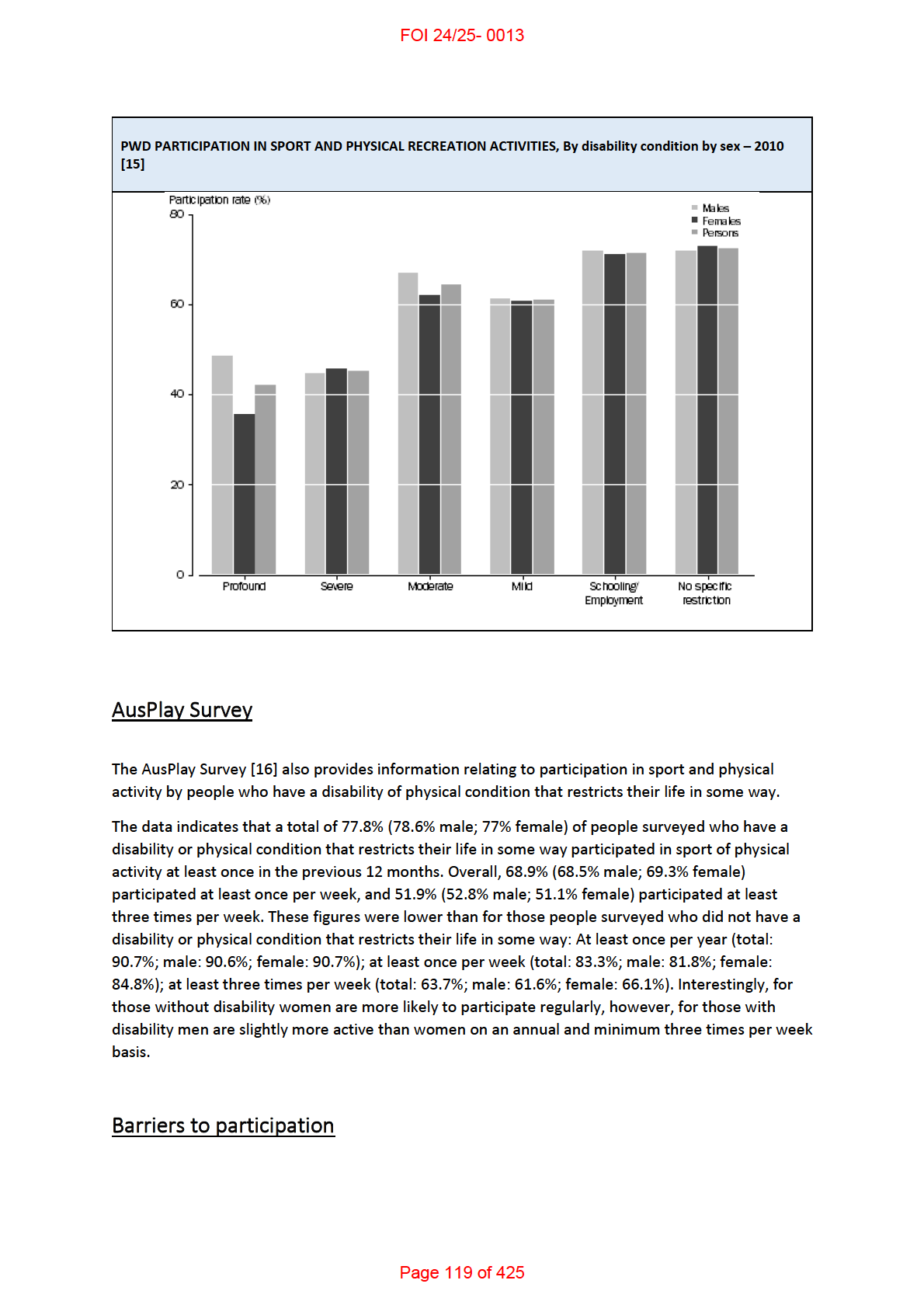

Disability Condition ....................................................................................................................... 15

AusPlay Survey .................................................................................................................................. 16

Barriers to participation .................................................................................................................... 16

Overview ....................................................................................................................................... 17

Barrier themes and sub themes in the research........................................................................... 17

References ............................................................................................................................................ 19

Summary

• Academic research investigating the benefits of solo recreational activities is limited. Studies

mainly focus on exercise and fitness within various cohorts (mainly older adults). The limited

research indicates that group based activities are more beneficial than solo activities.

• Statistical data on the number of recreational activities engaged by the average Australian

could not be sourced, however frequency of participation in sporting activities and the types

of activities could be.

o Australia’s Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines provides an

indication of broad time and frequency data of activity per week for adults and

children.

o Recent Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data shows that overall, two thirds of

people with a disability participated in sport and physical recreation activities in the

12 months prior to ABS interview.

• There is plentiful research available regarding participation in recreation and sport for

people with a disability. The majority of the research appears to be around the early 2000’s.

Page 105 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

However there are some relatively recent systematic reviews available. From these a general

overview of identified barriers can be gleaned. Research investigating barriers associated

with assistive technology is limited.

Benefits of solo recreational activities

Overview

There is a variety of popular internet and open source literature which asserts the pros and cons of

individual or group activities, however there is little academic research on the benefits of solo

recreational activities as opposed to participating in activities in a group environment. The research

available mainly focuses on exercise and fitness within various cohorts and more so in adults.

Of the

limited research on the subject there was a trend towards group based activities having greater

health benefits than solo activities, however, there was no consensus around preference for

individual versus group exercise across studies.

Adults and exercise

Three studies were sourced which suggested that exercise intervention for older adults be directed

at an individual level:

• A 1999 study examined preferences for exercising individual y with some instruction

compared to a class environment in 1,820 middle-aged and 1,485 older adults. The study

identified subgroups, 5 of middle-aged and 6 of older adults, whose preferences for

exercising on their own with some instruction ranged from 33–85%. Less educated women

under 56 years of age, healthy women 65–71, and older men reporting higher stress levels

were more likely to prefer classes. All other men and most women preferred exercising on

their own. Overall, 69% of middle-aged and 67% of older adults preferred to exercise on

their own with some instruction rather than in an exercise class. [1]

• A large-scale, cross-sectional survey, set out to explore personal, program based and

environmental barriers to physical activity among a U.S. population-derived sample of 2,912

women 40 years of age and older. Factors significantly associated with inactivity included

American Indian ethnicity, older age, less education, lack of energy, lack of hills in one's

neighbourhood, absence of enjoyable scenery, and infrequent observation of others

exercising in one's neighbourhood. For al ethnic subgroups, caregiving duties and lacking

energy to exercise ranked among the top 4 most frequently reported barriers.

Approximately 62% of respondents rated exercise on one's own with instruction as more

appealing than undertaking exercise in an instructor-led group, regardless of ethnicity or

current physical activity levels. The study suggested that the results underscore the

importance of a multifaceted approach to understanding physical activity determinants in

this understudied, high-risk population. [2]

• A survey by King, Taylor [3] focused on worksite exercise programs, and noted that while

worksite exercise programs offer a number of potential advantages with respect to

Page 106 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

increasing physical activity levels in American adults, typical participation rates remain

relatively low. The purpose of the study was to explore employee preferences and needs

related to physical activity programming in a major work setting in northern California. Male

and female employees reporting no regular aerobic activity over the previous two years,

more strongly endorsed a number of erroneous beliefs concerning exercise, reported less

support for engaging in exercise both at home and at work, and avoided even routine types

of activity to a greater extent than more active individuals. Current exercisers reported use

of a greater number and variety of motivational strategies as part of their exercise program

than past exercisers who were not currently active. Respondents, regardless of exercise

status and age, reported preferences for moderate-intensity activity occurring away from

the workplace which could be performed on one's own rather than in a group or class. [3]

In contrast, several studies have found that group based interventions are more beneficial. A large

scale questionnaire performed by Beauchamp, Carron [4] examined the exercise preferences of 947

adults for involvement in standard exercise classes populated by participants from various

categories across age groups. The results revealed that when faced with the prospect of exercising

with considerably older or younger exercisers, participants found such an exercise context to be

largely unappealing. However, in accordance with the basic tenets of self-categorization theory, the

results revealed that older and younger adults alike express a positive preference for exercising in

standard exercise classes comprised of similarly aged participants. Self-categorization is the process

used to place the self and others into different social categories based on underlying attributes (e.g.,

age, gender, race, education).

The study suggested that group related intervention strategies may indeed be attractive to older

exercisers. In summary:

• Older and younger adults alike reported a positive preference for exercising in standard

exercise classes comprised of others of a similar age.

• Participants reported that the prospect of exercising in standard exercise groups comprised

of exercisers dissimilar in age to themselves (older or younger) is largely unappealing.

• There were no significant differences across the age categories sampled in this study in their

preferences to exercise alone.

• Older adults did not show a greater preference to exercise alone as opposed to exercising in

age-matched group-based settings.

Furthermore, a 2016 cohort study [5] focused on whether the association of regular exercise to

subjective health status differs according to whether people exercise alone and/or with others,

adjusting for frequency of exercise. The study was based on the Japan Gerontological Evaluation

Study (JAGES) Cohort Study data. A total of 21,684 subjects aged 65 or older participated in the

study.

Page 107 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

Multivariable logistic regression models were used to examine the association between variables.

The adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for poor self-rated health were significantly lower for people who

exercised compared to non-exercisers.

Analysis of regular exercisers showed that the ORs for poor health were:

• 0.69 (95% confidence intervals: 0.60–0.79) for individuals exercising alone more often than

with others

• 0.74 (0.64–0.84) for people who were equal y likely to exercise alone as with others

• 0.57 (0.43–0.75) for individuals exercising with others more frequently than alone

• 0.79 (0.64–0.97) for individuals only exercising with others compared to individuals only

exercising alone

In summary the study suggested that:

• Although exercising alone and exercising with others both seem to have health benefits,

increased frequency of exercise with others has important health benefits regardless of the

total frequency of exercise.

Adults with chronic health conditions

A 2017 Australian randomised control trial (RCT) [6] looked at the effectiveness of gym-based

exercise versus home-based exercise with telephone fol ow-up amongst adults with chronic

conditions. The participants were recruited following a 6-week exercise program at a community

health service. One group of participants received a gym-based exercise program for 12 months

(gym group). The other group received a home-based exercise program for 12 months with

telephone fol ow-up for the first 10 weeks.

Participants allocated to the gym-based intervention were given a 12-month, individualised, exercise

program. An exercise physiologist from the community health service supervised this at the gym

from Monday to Friday for 2 hours per day. Participants were encouraged to attend during the times

the exercise physiologist attended the gym.

Participants allocated to the home-based intervention were also given a 12-month, individualised,

exercise program. Each participant was encouraged to complete a 1-hour exercise session, three

sessions per week, at home. The home-based exercise program was supervised via five telephone

calls over the first 10 weeks, approximately 25 to 30 minutes in duration. The total time in minutes

to complete the five phone calls for each participant was comparable to that spent supervising each

participant in the gym over a 12-month intervention period.

The study concluded that:

• Adults with a chronic disease who have recently completed a supervised exercise program

achieve similar outcomes and maintain similar exercise adherence a year later with either a

gym-based maintenance exercise program or a home-based maintenance exercise program

with telephone support.

• The gym-based program may improve mental health outcomes more, but the finding

requires further investigation.

Page 108 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

Adults with Psychological Distress

A 2017 thesis [7] investigated the effectiveness of group versus solo physical activity in the reduction

of psychological distress (including stress, depression and anxiety) and factors involved in

participation to promote greater engagement in physical activity.

The thesis found that group

physical activity may be associated with reduced psychological distress and be more beneficial in

protecting against psychological distress than solo physical activity. Three studies were carried out:

• The first study issued questionnaires to members of the general population and university

students. Inverse correlations were found between group physical activity and psychological

distress in both samples. However, a single positive correlation was found between anxiety

and solo physical activity in the student sample, which suggests that group physical activity

may be more effective in the reduction of psychological distress than solo physical activity.

Low active individuals appeared to prefer solo physical activity to group, which may be due

to lower perceived barriers. More active participants either preferred group activity or had

no preferences between group and solo activity, despite also perceiving greater barriers to

group than solo activity.

• The second study al ocated university students to a group versus solo jogging condition

intervention and found that psychological distress increased for those allocated to solo

jogging, but did not increase amongst those al ocated to group jogging, suggesting that

group physical activity may protect against university related distress. Those al ocated to

group jogging engaged in (non-significantly) more jogging and engaged in significantly more

moderately intensive physical activity throughout the intervention than those al ocated to

solo jogging.

• The final study compared group and solo physical activity using the Theory of Planned

Behaviour and structural equation modelling. The model explained more variance in group

physical activity than variance in solo physical activity. When the model was expanded, self-

efficacy made a significantly greater contribution to intention in the solo physical activity

model than it did in the group activity model, therefore promotion of group physical activity

may not be as dependent on self-efficacy as solo physical activity.

Recreational activities engaged by the average

Australian

Page 109 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

Guidelines for Children and Young people (5-7 years)

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

• Accumulating 60 minutes or more of moderate to vigorous physical activity per day involving

mainly aerobic activities.

• Several hours of a variety of light physical activities;

• Activities that are vigorous, as well as those that strengthen muscles and bones should be

incorporated at least 3 days per week.

• To achieve greater health benefits, replace sedentary time with additional moderate to

vigorous physical activity, while preserving sufficient sleep.

SEDENTARY BEHAVIOUR

• Break up long periods of sitting as often as possible.

• Limit sedentary recreational screen time to no more than 2 hours per day.

• When using screen-based electronic media, positive social interactions and experiences are

encouraged.

People with a disability (Types of recreational

participation and barriers to participation)

Overview

Data from the ABS provides participation rates for people with a disability, although not across all

age groups. This is a limiting factor as it has been suggested that participation declines with age. The

current data shows that overall, over two thirds of people with a disability participated in sport and

physical recreation activities. ABS data was also able to give some indication of participation by

gender, disability type and disability condition.

The AusPlay survey data was able to give an indication of frequency of participation by gender.

Academic research investigating the barriers to participation is plentiful although recent research is

limited. Five systematic reviews were sourced to give a general overview of the barriers to

participation categorised by Personal, Social, Environmental, and Policy & Program.

Page 115 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

Overview

Although research into the barriers to participation in recreation of people with a disability is

plentiful, the majority of the research appears to be around the early 2000’s. However, there are

some relatively recent systematic reviews available. This paper sourced five systematic reviews,

three focusing on adults and children and two focusing on children only. One review [17] combined

adults and children within its results, whilst the others separated age groups.

The research clearly identifies the overall barriers to participation, however, there is minimal work

which focuses on whether AT, or lack thereof it acts as a barrier.

Barrier themes and sub themes in the research

All reviews sourced broke down their findings into barrier categories, and although the categories

differ between the reviews, their content is common. For the purpose of this paper the fol owing

barriers categories will be used to accommodate the common barriers found in the reviews

(

Personal, Social, Environmental, and Policy & Program) and divided into Children, and Adults and

Children.

Following is a general overview of the barriers identified within the research sourced.

Personal Barriers

CHILDREN

• Lack of skills (physical and social) [18, 19]

• Lack of time [19, 20]

• Preference for activities other than physical activities [18]

• Fear and a lack of knowledge about exercise [18]

• Children with disability also disliked having to deal with negative perceptions of disability

(referred to as the "stigma of disability") or of attracting unwanted attention [18]

• Physical activities and sports are not fun [19]

• Lack of interest, motivation and enjoyment [19]

• Preference for sedentary behaviour [19]

• Increasing age (causes fear and lack of motivation) [19]

• Financial restrictions [19]

• Children and adolescents with different types of disabilities mentioned each disability itself

as a personal barrier [20]

• Unequal time distribution of the parents between the disabled child and their siblings [20]

CHILDREN AND ADULTS

• Psychological affect and emotion, attitudes/beliefs/perceived benefits and self-perceptions

[17]

• Body functions [17]

Page 120 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

• Negative mood, depression, anxieties, fears, and embarrassment related to activity [17]

• Health symptoms and conditions, pain, fatigue, energy, and strength [17]

• Lack of energy and fatigue with different types of disabilities [20]

• Employment status [17]

• knowledge about the benefits of physical activity and how to exercise [17]

• Financial costs [17]

Social Barriers

CHILDREN

• Parental actions (time constraints, travel, lack of knowledge) [18, 19]

• Behaviour or concerns (safety, child’s behaviours) [18, 19]

• A lack of friends to participate with or unsupportive peers and negative societal attitudes to

disability [18, 19]

• Parents of children with spina bifida reported that they believed recreation was more

important for children without disability [18]

• Mothers of school-aged children with Down syndrome reported their child’s interest in

physical activity waned as the gap between their motor skills and the motor skills of their

peers with typical development widened [18]

• Some children with disability chose not to participate in activity because they believed their

peers viewed them as helpless or the parents of their peers without disability were

unfriendly and had misconceptions about their ability [18]

CHILDREN AND ADULTS

• Support from family, friends, peers, health-care and other professionals for facilitating

physical activity [17]

• Other people’s negative attitudes [17]

Environmental Barriers

CHILDREN

• Inadequate, inaccessible or inconvenient facilities [18, 19]

• Lack of transport [18, 19]

• Almost 80% of parents of children with disability (mean age 7 years) reported that a lack of

facilities was a major barrier [18]

CHILDREN AND ADULTS

• Building/facility accessibility and location [17]

• Design, construction and building products and technology of buildings for public use [17]

• Lack of Equipment/ Accessibility of adaptive equipment [17, 21]

Page 121 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

• Suitability of climate [17]

• Lack of transportation [17, 20, 21]

• Financial costs [20, 21]

• Lack of information about sports [20]

• Lack of sports possibilities [20]

Policy & Program Barriers

CHILDREN

• Lack of appropriate physical activity programmes [18]

• Lack of staff capacity, negative staff attitudes towards working with children with disability

and cost [18, 19]

• Between 25% and 60% of parents in four studies identified a lack of appropriate

programmes or a deficiency in available programmes as a barrier [18]

• Forty per cent of children with disability also felt they had a lack of opportunities to be

physically active and 35% believed there was a lack of transition programmes from the

rehabilitation setting to a community setting or that there was a lack of ‘learn to exercise’

programmes [18]

• Some children were excluded from formal programmes because of specified rules and

regulations, for example, motorised wheelchairs were not allowed in a wheelchair basketball

competition [18]

CHILDREN AND ADULTS

• Knowledge of people within institutions/organisations, rehabilitation processes, building

design and construction [17]

• Education and training of professionals in the areas of accessibility and appropriate

interactions [21]

• Knowledge among health-care professionals and other service providers [17]

• Physical activity information, counselling, and encouragement from rehabilitation

professionals [17]

• Need for training of staff/professionals within the organisations [17]

• Restrictive policies and bureaucracy [17]

• Perceptions and attitudes of both professionals and nondisabled individuals toward

accessibility and persons with disabilities [21]

References

1.

Wilcox S, King A, Brassington G, Ahn D. Physical Activity Preferences of Middle-Aged and

Older Adults: A Community Analysis. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 1999;7(4):386-99.

2.

King AC, Castro C, Wilcox S, Eyler AA, Sallis JF, Brownson RC. Personal and Environmental

Factors Associated With Physical Inactivity Among Different Racial–Ethnic Groups of U.S. Middle-

Aged and Older-Aged Women. Health Psychology. 2000;19(4):354-64.

Page 122 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

3.

King AC, Taylor CB, Haskell WL, DeBusk RF. Identifying strategies for increasing employee

physical activity levels: findings from the Stanford/Lockheed Exercise Survey. Health Educ Q.

1990;17(3):269-85.

4.

Beauchamp MR, Carron AV, McCutcheon S, Harper O. Older adults’ preferences for

exercising alone versus in groups: Considering contextual congruence. Annals of behavioral

medicine. 2007;Vol.33(2):200-6.

5.

Satoru K, Tomoko T, Shigeru I, Yuko K, Ichiro K, Katsunori K. Exercising alone versus with

others and associations with subjective health status in older Japanese: The JAGES Cohort Study.

Scientific Reports. 2016;6(1).

6.

Jansons P, Robins L, O’brien L, Haines T. Gym-based exercise and home-based exercise with

telephone support have similar outcomes when used as maintenance programs in adults with

chronic health conditions: a randomised trial. Journal of physiotherapy. 2017;63(3):154-60.

7.

Port J. Group versus solo physical activity in the reduction of stress, anxiety and depression.

ProQuest Dissertations Publishing; 2017.

8.

Australian Sports Commission. AusPlay survey results January 2019 - December 2019 2020

[Available from: https://www.clearinghouseforsport.gov.au/research/ausplay/results.

9.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Participation in Sport and Physical Recreation, Australia 2014

[02/11/20]. Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-

communities/participation-sport-and-physical-recreation-australia/latest-release.

10.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Sports and Physical Recreation: A Statistical Overview,

Australia, 2012 2012 [10/11/20]. Available from:

https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Products/76DF25542EE96D12CA257AD9000E2685.

11.

Sport NGOo. Participation in sport and active recreation 2020 [Available from:

https://www.sport.nsw.gov.au/sectordevelopment/participation#:~:text=Children%E2%80%99s%20

participation%20in%20organised%20sport%20or%20physical%20activity,%20%20%2A%20%202%20

more%20rows%20.

12.

Australian Government | Department of Health. Australia's Physical Activity and Sedentary

Behaviour Guidelines and the Australian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines 2020 [Available from:

https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-pubhlth-strateg-phys-

act-guidelines#npa1864.

13.

Australian Government | Department of Health. Development of Evidence-based Physical

Activity Recommendations for Adults (18-64 years) 2013 [Available from:

https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/F01F92328EDADA5BCA257BF00

01E720D/$File/DEB-PAR-Adults-18-64years.pdf.

14.

Australian Sports Commission. Participation 2020 [Available from:

https://www.clearinghouseforsport.gov.au/kb/persons-with-disability-and-sport/participation-

statistics.

15.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Participation in Sport and Physical Recreation by People with

a Disability 2013 [11/11/20]. Available from:

https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Products/4156.0.55.001~July+2012~Main+Features~Par

ticipation+in+Sport+and+Physical+Recreation+by+People+with+a+Disability?OpenDocument.

16.

Australian Sports Commission. AusPlay survey results July 2016-June 2017 [Website]. 2017

[Available from: https://www.clearinghouseforsport.gov.au/research/ausplay/results.

17.

Martin Ginis KA, Ma JK, Latimer-Cheung AE, Rimmer JH. A systematic review of review

articles addressing factors related to physical activity participation among children and adults with

physical disabilities. Health Psychology Review. 2016;10:4, 478-494.

18.

Shields N, Synnot AJ, Barr M. Perceived barriers and facilitators to physical activity for

children with disability: a systematic review. British journal of sports medicine. 2012;46(14):989-97.

19.

Bloemen MAT, Backx FJG, Takken T, Wittink H, Benner J, Mol ema J, et al. Factors associated

with physical activity in children and adolescents with a physical disability: a systematic review.

2015. p. 137-48.

Page 123 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

20.

Jaarsma EA, Dijkstra PU, Geertzen JHB, Dekker R. Barriers to and facilitators of sports

participation for people with physical disabilities: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of

Medicine and Science [Internet]. 2014; 24(6):[871-81 pp.].

21.

Rimmer JH, Riley B, Wang E, Rauworth A, Jurkowski J. Physical activity participation among

persons with disabilities. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;26(5):419-25.

Page 124 of 425