FOI 24/25- 0013

DOCUMENT 25

Home automation as an everyday living cost

The content of this document is OFFICIAL.

Please note:

The research and literature reviews collated by our TAB Research Team are not to be

shared external to the Branch. These are for internal TAB use only and are intended to

assist our advisors with their reasonable and necessary decision-making.

Delegates have access to a wide variety of comprehensive guidance material. If

Delegates require further information on access or planning matters, they are to call the

TAPS line for advice.

The Research Team are unable to ensure that the information listed below provides an

accurate & up-to-date snapshot of these matters

Research question: How common is home automation/”smart homes” in Australia?

What is the typical ‘scope of works’ for a standard ‘smart home’ vs disability-specific home

automation features?

What is the typical cost or price range to setup a ‘smart home’?

Are existing homes able to accommodate home automation without needing to upgrade

electrical features (e.g. switchboard, wiring)?

Is there a significant dif erence in outcomes between low cost solutions (e.g. Google Home)

and high cost solutions (e.g. Control 4)?

What is the current evidence base regarding home automation and people with disability? Is

there evidence home automation is linked to increased independence, or other positive

outcomes (e.g. improved quality of life, wellbeing)? Are there any best practice guidelines?

What is the Agency’s risk appetite for home automation requests? Do mitigation strategies

need to be put in place (e.g. TAB mandatory referral for requests above $20,000)?

Date: 09/05/2022

Requestor: Claire s22(1)(a)(ii)

- irrele

Endorsed by (EL1 or above): Sandi s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant material

Researcher: Aaron s22(1)(a)(ii)

- irrelevant ma

Cleared by: Stephanie s22(1)(a)(ii)

- irrelevant mate

Page 278 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

1. Contents

Home automation as an everyday living cost ............................................................................. 1

1.

Contents ....................................................................................................................... 2

2.

Summary ...................................................................................................................... 2

3.

What is home automation? ........................................................................................... 3

4.

Home automation in Australia ....................................................................................... 4

5.

Home automation as a disability support ...................................................................... 4

5.1 Benefits ...................................................................................................................... 5

6.

Risk ............................................................................................................................... 7

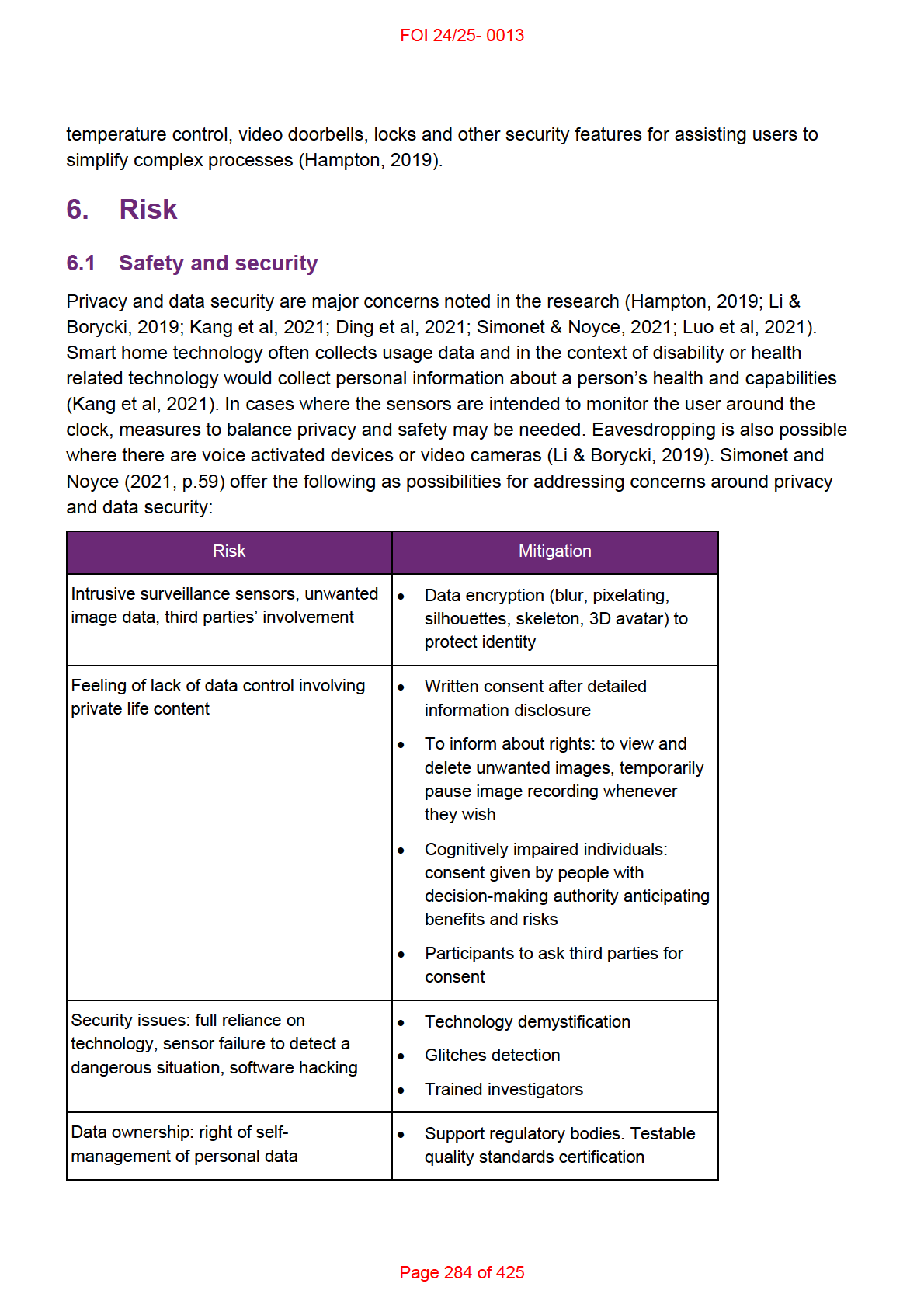

6.1 Safety and security .................................................................................................... 7

6.2 Cost effectiveness ..................................................................................................... 8

7.

References ................................................................................................................. 10

8.

Version control ............................................................................................................ 12

2. Summary

Smart home technology is growing in popularity in Australia. Most people having at least one

smart home device in their home. While common, only certain types of automations (eg.

entertainment) are ubiquitous in Australian homes. Whether a particular home automation

support is more likely an everyday living cost wil depend on the type and function of the

technology.

With the technology growing and changing, there is inconsistent and outdated information

online. Much of the research is still in very early stages and so the evidence base is minimal.

There is more research focussing on maintaining independence of older people compared to

other disability cohorts.

There is a body of research focussed on using sensors and the Internet of Things (IoT) in the

home to monitor and assess people at risk of various harms (for example, trips or falls, burns

when cooking etc.). Although home automations are often integrated with IoT, this paper will

only discuss IoT technology when it relates to automating processes in the home. Similarly,

there is a strong research focus on use of robotics to automate processes in the home (for

example, a robot vacuum to clean the floor). There may not be distinct boundaries between

home automations and robotics, but this paper will focus on the automation of processes

related to structure or fixtures of the house and environment (for example, automated lights,

doors or heating/cooling systems).

Page 279 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

From the available information it appears that for most common home automations, off-the-

shelf control units like Google Home, Apple Home kit or Amazon dot may be sufficient with

installation of automated appliances or fixtures. If these mainstream options are not accessible

for a user, or if they require a more customised solution, then specialised home automation

systems may be required.

Currently, we do not have accurate information about how often home automations are funded

and what the average costs that quotes are implemented for. Without this information we

cannot accurately determine financial risk to the scheme.

3. What is home automation?

Anything that moves or turns on and off can be automated. In a house, this can include lights,

electricity outlets, doors, windows, drawers, blinds, locks, showers, baths, sinks, toilets, air-

conditioning, ceiling fans, platform or stair lifts, cameras, intercoms, alarms or other security

features, watering or reticulation systems. Any home appliance can be automated including

TVs, sound systems, vacuums, fridges, kettles and coffee makers etc.

Home automations, sometimes called domotics, can be linked or integrated via home internet

or wireless technology and operated via phones, tablets, computers or dedicated control

interfaces, allowing users to control structural or environmental features of their home. A home

in which automation is integrated with the Internet of Things is often called a smart home (Choi

et al, 2021; Katre & Rojatkar, 2017). The Internet of Things refers to a network of computing

devices which can communicate with each other via a system of sensors (Choi et al, 2021).

For example, a bedroom light turns on when the bedroom door is opened thanks to a sensor in

the door, or a wearable temperature sensor can send information to an air-conditioner to

regulate the room temperature. This is an example of an automated system with a passive

input. It’s called passive because the user does not have to intentionally turn the light on, it is

turned on by doing another activity the user would have done anyway (opening the door). This

contrasts with active input, in which the user speaks or operates controls on a tablet or phone

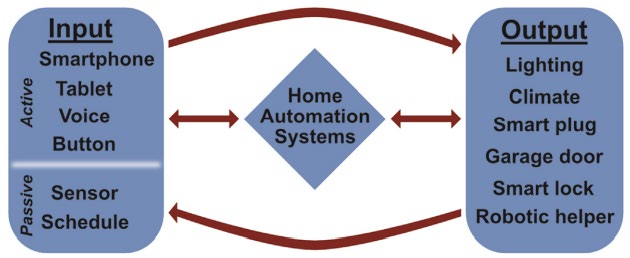

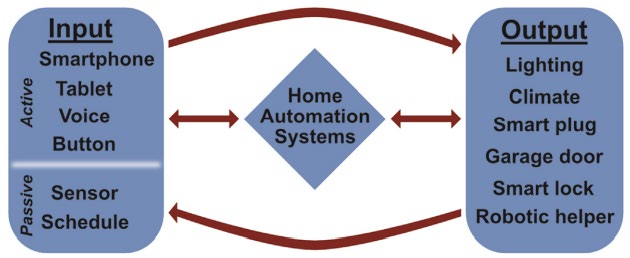

(Hampton, 2019). Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between inputs and outputs in a home

automation system.

Figure 1: Home automation systems. Source: Hampton, 2019.

Page 280 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

4. Home automation in Australia

There is little reliable data on the prevalence of home automations in Australian households.

The information that is available was gathered for commercial purposes and may have

inherent bias. Data from the Statista Global Consumer survey of 2049 people found 85% had

some smart home device in their house. Entertainment devices are the most common (79%),

followed by:

• devices for monitoring and automating electricity and lighting (30%)

• safety and security (29%)

• smart appliances (26%)

• smart speakers with virtual assistant (22%)

• energy management (22%) (Statista 2022).

A 2022 Savvy survey of 1000 people found 48% aged over 55 have at least one smart home

device and 41% have 5-10 devices. 58% of people 18-44 have at least one smart home device

in their home (Chavda, 2022). Due to barriers accessing the ful datasets or reports for these

surveys, the definitions of ‘smart device’ or ‘smart home device’ are not clear. They may

include devices as common as Bluetooth speakers or motion sensor lights. Also, information

substantiating the representativeness of the survey group is not available.

5. Home automation as a disability support

There is no standard home automation scope of works in either a mainstream or disability

support context. However, based on a review of 20 TAB advice requests from 2021/2022,

common automation requests include:

• doors and locks

• windows and blinds

• lighting (ceiling lights or lamps)

• heating/cooling (air-conditioner, ceiling fans)

• intercom / video doorbell

• entertainment (TV, sound systems).

In a mainstream context, the goals of home automation include safety and security, comfort,

convenience and energy efficiency (Statista, 2022). Features designed for comfort or

convenience in a mainstream context can have significant implications for independent living

for people who live with a disability (Hampton, 2019). A 2021 survey of allied health

practitioners found commercially available home automation technology has been used to

assist people with traumatic brain injury, spinal cord injury, cerebral palsy, amyotrophic lateral

sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, stroke, dementia, Alzheimer’s, mild cognitive impairments, autism,

Page 281 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

Parkinson’s disease, low vision or blindness, and Down syndrome (Ding et al, 2021). Home

automation can be useful to:

• remove physical barriers to the use of fixtures or appliances

For example, the automation of doors, windows, and blinds can be used to change the

usual physical input (pushing, lifting, reaching, pulling) which a user might have difficulty

with to a different input within the user’s ability (speaking a voice command, using a

touch screen).

• prompt a user to complete daily activities

For example, a user might require prompting to brush their teeth in the morning, so they

install a sensor on the bedroom door which triggers a voice prompt when the user first

leaves their bedroom in the morning.

• simplify complex process

For example, if a user has difficulty remembering everything they need to do to secure

their house when they leave, multiple processes (lock doors, close windows and blinds,

turn off all lights and appliances), could be activated via a single input (press a single

button on their smartphone).

5.1 Benefits

Research focussing on the use of home automation in a disability, health or ageing context is

only a smal portion of the research literature on home automation (Li et al, 2022; Choi et al,

2021). Despite this, healthcare was one of the first applications of smart home research

represented in the literature. This body of research looks at technology for monitoring health of

patients, improving service delivery and promoting ageing in place.

Much of the literature on the effectiveness of home automation or Smart home technology

focusses on home care for older people (Lee & Kim, 2020; Tural et al, 2021; Astasio-Picado et

al, 2022). This literature has shown that smart home technology including sensors, automated

lighting, locks and fire detection devices can reduce hospitalisation among older adults,

improve feelings of safety and security and promote ageing in place. However, since the focus

is on older people, the results may not generalise across disability cohorts.

Research into the use of home automation in a disability context is still developing. As late as

2008, a Cochrane review found no randomised controlled trials, quasi‐experimental studies,

controlled before and after studies or interrupted time series analyses looking into home

automation as a treatment for people with physical disability, cognitive impairment or learning

disability. Noting that these technologies are in use, the authors recognise that technology

often finds its way into the healthcare industry “without comprehensive evaluation of the health

impact or a true understanding of the added value of ICT to health services” (Martin et al,

Page 282 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

2008, p.5). Research also often develops slower than technology, so that by the time research

is completed, a technology may be obsolete (TAC, n.d).

The evidence base is still minimal though preliminary studies show a positive effect of home

automation. A 2021 review into the use of home automation and smart home technology for

people with Parkinson’s found benefit in improving autonomy and safety, but this is primarily

using sensors and data-collection to inform health care providers of risks (Simonet & Noyce,

2021). Two pilot studies into the use of home automation found improvements in social

adaptation, activities of daily living and quality of life for people with Parkinson’s disease

(Latella et al, 2021) and improvements in social and cognitive functioning and autonomy in

people with chronic stroke (Maggio et al, 2020). However, both pilot studies measure use of

home automation in short sessions rather than as a ubiquitous living environment.

Victoria’s Transport Accident Commission has funded a research project looking at smart

home technology for supporting memory, planning and organisation. The research is

scheduled to be completed in 2022 (TAC, n.d.).

Removing physical barriers. There is some evidence on the usability and accessibility of

control systems for operating common home automations (Masina et al, 2020; Conado et al,

2022). For example, Masina et al (2020) found accessibility issues in the use of voice

assistants (Siri, Alexa, Cortana etc) for people with cognitive and linguistic impairments. I have

found no evidence relating to the effectiveness of common home automations to remove

physical barriers. This may be due to the early stages of the evidence base or the typical

heterogeneity of new technologies. It may also relate to the fact that home automations

straight-forwardly allow people to perform these basic activities (turn lights on and off, open

doors and windows) provided the controls are accessible.

Prompting. A 2015 study into prompting technology found an effective prompting system:

can improve the efficacy of cognitive interventions, minimize the necessity for human

assistance, and allow users to feel more independent. Research has shown that

prompting technologies can enhance medication adherence, improve the use of

external compensatory strategies, reduce caregiver burden, and increase functional

independence in those with cognitive impairment (Robertson et al, 2015, p.9).

The authors note prompting is most ef ective during points of transition (when finishing or

starting a different activity) and less effective when the prompt occurs at a specific time of day

regardless of what the user is doing (for example, a reminder set for 8:30am every day). Smart

home technology can facilitate prompting triggered by certain activities (leaving or entering a

room, getting out of bed, turning an appliance on or off) and so may be more targeted than

simple time-of-day prompts.

Simplifying complex processes. In a 2019 introduction to home automation, Hampton

suggested there was no significant evidence base for the effectiveness of home automation for

people with disability. However, he does acknowledge the usefulness of automated lights,

Page 283 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

Other risks relate to networking and remote operation of basic household processes. If a

device is connected to a user’s Wi-Fi and there is a network failure this may cause be safety

issues such as the inability to open or unlock doors. This might be mitigated by systems which

connect via Bluetooth or Z-Wave and do not depend on Wi-Fi network. If a smart home system

is hacked, all the automated systems may be vulnerable to remote operation. This may be

mitigated by appropriate digital security measures. In addition, remote operation of doors and

locks raises concerns of restrictive practice. This risk could be mitigated by limiting number of

users with access to the systems and identifying if a behaviour support plan involving

restrictive practice is required.

6.2 Cost effectiveness

I have not found any research on the cost effectiveness of home automations compared to

personal assistance. There is a suggestion in the literature that home automation can increase

independence and reduce carer burden, but this is not quantified into reduced hours of

support. In theory, a person who only requires monitoring over the day could reduce the

amount of on-site care they require. However, for both on and off-site care, reduced hours

would depend on the support arrangement in place. There is some evidence that a person

only requiring prompting to complete daily activities could rely less on personal assistants and

therefore reduce care hours (5.1 Benefits). However, I have not seen any evidence showing

that home automations designed for prompting do reduce support hours.

As such, we cannot say that home automations have a track record of reducing support hours

and we cannot say in general that home automations are likely to be value for money.

Individual requests for funding may be able to demonstrate a likely reduction in support hours

or some comparable benefit that would make the request value for money. For example, if a

participant can sometimes navigate the community independently and an automated door will

enable them to enter or exit their home independently, then the request may increase their

independence to an extent that funding would be justified, even if it does not reduce support

hours.

There is inconsistent information available when comparing mainstream smart home hubs

(Google Home, Amazon Dot, Samsung SmartThings, Apple HomeKit etc) with more

specialised control units (C-Bus, Crestron, Mobotix, Control 4). This may be due to the

commercial nature of the reviews and the rapid progress of the technology. Most online

reviews compare mainstream hubs with each other or specialised control units with each

other, but do not compare mainstream with specialised.

Specialised units require more set-up and are more costly but allow for greater customisation.

Mainstream hubs are cheaper, fulfill most basic automation needs but their interface is less

customisable and may be less accessible. I have not found a home automation technology

designed specifically for people with disabilities, though with some specification both

mainstream hubs and specialised units can accommodate some accessibility measures. The

most cost-ef ective system will depend on the needs of the individual.

Page 285 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

For example, Apple Home is a free app which works with various accessories. It advertises the

ability to automate or work with air conditioners, air purifiers, bridges, cameras, doorbells, fans,

garage doors, humidifiers, lights, locks, power points, receivers, routers, security, sensors,

speakers, sprinklers, switches, taps, thermostats, TVs, and windows. It is compatible with

hundreds of products of various brands (Apple Home).

Google Home setups are currently selling for $99 and can automate several processes

independently (email, phone, entertain systems) and can link to additional modules (for

example, Samsung’s SmartThings) to:

lock and unlock doors, regulate air-con settings, open and close windows blinds, water

plants, start robotic vacuum cleaners, and arm and disarm alarm systems, [operate]

plug and power outlet, motion sensor, security camera, Honeywell thermostat, garage

door opener, washing machine, door bell and garden irrigation controller (Noda, 2018,

p.675).

Mainstream smart home hubs are inexpensive but require compatibility with devices or fixtures

in the home. This can involve buying new appliances or separately automating household

processes, which can sometimes involve substantial costs.

An additional consideration is re-wiring of a home. Mainstream accessories (lights and

appliances) and accessories or systems that run on batteries will often not need re-wiring.

Many home automation systems or devices need neutral wires and so some older homes may

require re-wiring. Some people choose to install deep junction boxes, wiring closets or higher

grade ethernet cables (Fritz, 2021; SmartHome, n.d., Tholen, 2021).

6.2.1 Reducing financial risk

When a request for home automation is determined to be reasonable and necessary a plan

developer includes the line item:

Environmental Control (ECU)/ Safety-Related Products 05_241303121_0123_1_2.

This is a quotable item in the Assistive Technology category with a benchmark of $17,474. The

line item for repair and maintenance is:

Repairs and Maintenance - Communication Cognitive or ECU AT

05_502200312_0124_1_2

and has a notional value of $500. Home automations are not a mandatory referral to TAB and

do not have any mandatory referral rules associated with them.

We do not currently have data on how frequently this line item is included in the plan and

whether the benchmark represents to average cost quotes are implemented for. However, this

information may be obtained from the Office of the Scheme Actuary. Without this information

we don’t have a good idea of the financial risk associated with these requests and we don’t

know if further risk mitigation strategies are required.

Page 286 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

However, without an idea of scale, some concerns and strategies are stil apparent. It is also

possible home automations are being included in plans without the line item or with a different

line item, contributing to the lack of clarity about how often this support is being funded. There

could be a few reasons for this. Home automations are funded through the Assistive

Technology category, though they sometimes blur the line between AT and Home

Modifications, requiring rewiring efforts or installation of built-in features like doors and

cabinetry. Plan developers may be looking to fund the support through the Home Modifications

budget. Environmental control unit is a technical term which may not be widely known. This

term may or may not be used in the request, assessment or quote and may not signal to the

plan developer to include the correct line item.

Either changing the name of the line-item to include a reference to home automation or

publicising the current line item and what it’s for could reduce the potential for home

automation funding being included via a different route.

Some risk reduction measures are introduced for supports costing above $15,000 such as a

full assessments and quotes. Risk of supports being funded that are not value for money could

be further reduced by creating a mandatory TAB referral rule (eg. mandatory referral to home

automations over $20,000).

Further support for decision makers might include adding a home automation example to the

Would We Fund It guide or adding a home automation advice request to the TAB digest.

7. References

Astasio-Picado, Á., Cobos-Moreno, P., Gómez-Martín, B., Verdú-Garcés, L., & Zabala-Baños,

M. (2022). Efficacy of Interventions Based on the Use of Information and

Communication Technologies for the Promotion of Active Aging.

International journal of

environmental research and public health,

19(3), 1534.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031534

Condado, P. A., Lobo, F. G., & Carita, T. (2022). Towards Richer Assisted Living

Environments.

SN computer science,

3(1), 96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-021-

00983-0

Chavda, S. (2022).

Smart home technology adoption rises with more Australians over 60

buying tech devices. Savvy. Retrieve May 6 2022, from

https://www.savvy.com.au/smart-home-technology-adoption-rises-with-more-

australians-over-60-buying-tech-devices/

Choi W, Kim J, Lee S, Park E. (2021) Smart home and internet of things: A bibliometric study.

Journal of Cleaner Production. 301, 126908

Ding, D., Morris, L., Messina, K., & Fairman, A. (2021). Providing mainstream smart home

technology as assistive technology for persons with disabilities: a qualitative study with

Page 287 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

professionals.

Disability and rehabilitation. Assistive technology, 1–8. Advance online

publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2021.1998673

Fritz, R. (2021). How to wire your New House for home automation. Lifewire. Retrieved May 6,

2022, from https://www.lifewire.com/preparing-new-house-for-home-automation-817661

Hampton S. (2019). Internet-Connected Technology in the Home for Adaptive Living.

Physical

medicine and rehabilitation clinics of North America,

30(2), 451–457.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2018.12.004

Katre S and Sojatkar D. (2017). Home automation: past, present and future.

International

Research Journal of Engineering and Technology,

4(10), 343-346.

Kang, H. J., Han, J., & Kwon, G. H. (2021). Determining the Intellectual Structure and

Academic Trends of Smart Home Health Care Research: Coword and Topic Analyses.

Journal of medical Internet research,

23(1), e19625. https://doi.org/10.2196/19625

Latella, D., Maggio, M. G., Maresca, G., Andaloro, A., Anchesi, S., Pajno, V., De Luca, R., Di

Lorenzo, G., Manuli, A., & Calabrò, R. S. (2021). Effects of domotics on cognitive, social

and personal functioning in patients with Parkinson's disease: A pilot study.

Assistive

technology : the official journal of RESNA, 1–6. Advance online publication.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.2020.1846095

Lee LN and Kim MJ (2020) A Critical Review of Smart Residential Environments for Older

Adults With a Focus on Pleasurable Experience.

Front. Psychol. 10:3080. doi:

10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03080

Li, C. Z., & Borycki, E. M. (2019). Smart Homes for Healthcare.

Studies in health technology

and informatics,

257, 283–287.

Li, W., Yigitcanlar, T., Liu, A., & Erol, I. (2022). Mapping two decades of smart home research:

A systematic scientometric analysis.

Technological Forecasting and Social Change,

179(121676), 121676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121676

Luo, H., Liu, X., & Wang, P. (2021). Safety risk analysis of Home Automation products.

Journal

of Physics. Conference Series,

1986(1), 012103. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-

6596/1986/1/012103

Maggio, M. G., Maresca, G., Russo, M., Stagnitti, M. C., Anchesi, S., Casella, C., Zichitella, C.,

Manuli, A., De Cola, M. C., De Luca, R., & Calabrò, R. S. (2020). Effects of domotics on

cognitive, social and personal functioning in patients with chronic stroke: A pilot study.

Disability and health journal,

13(1), 100838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2019.100838

Martin S, Kelly G, Kernohan WG, McCreight B, Nugent C. Smart home technologies for health

and social care support. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 4. Art.

No.: CD006412. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006412.pub2.

Masina, F., Orso, V., Pluchino, P., Dainese, G., Volpato, S., Nelini, C., Mapelli, D., Spagnolli,

A., & Gamberini, L. (2020). Investigating the Accessibility of Voice Assistants With

Page 288 of 425