FOI 24/25- 0013

DOCUMENT 21

Research – Dialectical Behavioural Therapy

The AAB have requested further information Dialectical Behavioural Therapy

(DBT).

The Applicant is a 23yo female with Asperger’s Syndrome, ASD and/or

Dissociative Identity Disorder.

In preparation for hearing of the matter, the AAB have requested a high level

review of DBT, in particular in application and effectiveness. They would also like

information to assist in determining whether DBT constitutes a treatment for

mental health and who would be responsible for funding treatment under

APTOS.

Further to above, please provide information on the treatment DBT, e.g. :

• What is DBT?

Brief

• What is the evidence base for DBT?

• What is the effectiveness of DBT?

• What is the general application of DBT?

• What conditions is DBT recommended for? (Particularly interested

in any application/ evidence for Asperger’s Syndrome, ASD and/or

Dissociative Identity Disorder)

• Is DBT a recommended for mental health conditions?

• What funding options are available for treatment of DBT? E.g.

under Health or Mental Health services

• Please provide a list of possible experts in DBT in Australia.

Date

23/06/21

Requester(s)

Michelle s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant material - Senior Technical Advisor (TAB/AAT)

Researcher

Jane s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelev - Research Team Leader (TAB)

Cleared

Please note:

The research and literature reviews col ated by our TAB Research Team are not to be shared external to the Branch. These

are for internal TAB use only and are intended to assist our advisors with their reasonable and necessary decision-making.

Delegates have access to a wide variety of comprehensive guidance material. If Delegates require further information on

access or planning matters they are to call the TAPS line for advice.

Page 202 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

The Research Team are unable to ensure that the information listed below provides an accurate & up-to-date snapshot of

these matters.

The contents of this document are OFFICIAL

1 Contents

2 Summary ......................................................................................................................................... 2

3 What is dialectical behavioural therapy? ........................................................................................ 3

4 Evidence base and effectiveness of dialectical behaviour therapy ................................................ 3

4.1

Other conditions where evidence of effectiveness exists ...................................................... 4

4.2

Dialectical behaviour therapy for the treatment of dissociative identity disorder ................ 4

4.3

Dialectical behaviour therapy for the treatment of autism spectrum disorder ..................... 5

5 What is the general application of DBT? ........................................................................................ 5

6 Available funding options ............................................................................................................... 7

6.1

Public services ......................................................................................................................... 7

6.2

Private services ....................................................................................................................... 7

7 Please provide a list of possible experts in DBT in Australia........................................................... 7

8 References ...................................................................................................................................... 9

2 Summary

• Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT) is the gold standard psychological treatment for

borderline personality disorder (BPD).

• The use of DBT has been suggested as an effective treatment option for the

treatment of Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID). Although no randomised controlled

trials exist, expert consensus and empirical research have found that DBT can be

adapted without significant changes to treat DID given the many similarities to BPD

such as self-harm, suicidal behaviour, emotion dysregulation, identity disturbance,

and dissociation.

• There are no studies to suggest DBT is useful for autism spectrum disorders.

• DBT can be funded through public and private mental health clinics.

• Treatment consists of one on one sessions, group skills training and telephone

coaching sessions.

Page 203 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

3 What is dialectical behavioural therapy?

DBT is a type of psychotherapy/talk therapy and a form of cognitive behavioural therapy

(CBT). It was originally designed to treat the problems of chronically suicidal individuals with

BPD. People with this BPD feel intense, uncontrol able emotions, have

troubled relationships and have a disturbed sense of self.

The approach is cal ed "dialectical" because it involves the interaction of two conflicting

ideas, which are that improving the symptoms of BPD involves both acceptance and change

[1].

It is designed to help people change unhelpful ways of thinking and behaving while also

accepting who they are. It helps patients learn to manage emotions by letting them

recognise, experience and accept themselves. DBT can also help patients understand why

they might harm themselves, so they are more likely to change their harmful behaviour.

DBT usual y includes [2]:

• individual sessions with a therapist

• skills training in groups

• telephone coaching sessions with a therapist if you are experiencing a crisis

DBT therapists often work in teams and help each other, so they can provide the best

treatment possible.

A typical course of DBT involves weekly individual therapy sessions (approximately 1 hour),

a weekly group skills training session (approximately 1.5–2.5 hours), and a therapist

consultation team meeting (approximately 1–2 hours) [2].

4 Evidence base and effectiveness of dialectical

behaviour therapy

DBT is currently the gold standard treatment for borderline personality disorder (BPD) and

an effective treatment for associated problems such as repeated self-harming, attempting

suicide, alcohol or drug problems, eat disorders, unstable relationships, depression, feelings

of hopelessness and post-traumatic stress disorder in this population [3]. It has been shown

to reduce the need for medical care and medications by as much as 90% [1].

A Cochrane Review which assessed the beneficial and harmful effects of psychological

therapies for people with BPD was conducted in 2020 [4]. Twenty-four randomised

Page 204 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

control ed trials (RCTs) were included that investigated DBT or modified DBT related

treatments.

Compared to treatment as usual (TAU), which includes various forms of psychotherapy,

DBT:

• Reduced BPD symptom severity, self-harm, anger, impulsivity, dissociation and

psychotic-like symptom and improved psychosocial functioning at end of treatment.

o These treatment effects are small to moderate in size, however, the evidence

was graded as low which means there is some uncertainty around the results.

• Did not reduce suicide related outcomes, affective instability, interpersonal

problems, depression or chronic feelings of emptiness compared to TAU.

No adverse effects were found.

Earlier systematic reviews and meta-analyses have come to similar conclusions in relation to

DBT for stabilising self-destructive behaviour, reducing suicide attempts and self-injurious

behaviours in people diagnosed with BPD [5-7].

4.1

Other conditions where evidence of effectiveness exists

• Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [8, 9]

• Substance abuse and addiction disorders [10, 11]

• Depression [12, 13]

• Eating disorders [14]

4.2

Dialectical behaviour therapy for the treatment of dissociative identity

disorder

Dissociative identity disorder (DID) is a complex post-traumatic disorder which is highly

comorbid with BPD. About two-thirds of people with BPD meet the criteria for a dissociative

disorder, and display features of BPD such as a high degree of suicidality [15-17].

There are no published randomized control ed trials investigating treatments for DID [15].

Empirical data and expert consensus developed by the International Society for the Study of

Trauma and Dissociation suggests that carefully staged trauma-focused psychotherapy can

result in a significant reduction in DID symptomology [18-20].

It has been argued by Foote and Van Orden [15] that DBT can be usefully adapted without

significant changes to treat DID given the many similarities to BPD such as self-harm, suicidal

behaviour, emotion dysregulation, identity disturbance, and dissociation [15].

Page 205 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

4.3

Dialectical behaviour therapy for the treatment of autism spectrum

disorder

Simular to DID, autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has overlapping traits with BPD such as

emotional dysregulation, self-harm and social difficulties [21].

Adapting DBT for the treatment of ASD has been suggested by various authors [22, 23].

However, only one non-randomised trial could be located that investigates DBT for ASD

[24]. This included delivering radically open dialectical behaviour therapy (RO DBT) which

has been developed as an adapted form of DBT to directly target over control. The study

showed the intervention was effective, with a medium effect size of 0.53 for improvement

in global distress. Participants with a diagnosis of ASD who completed the therapy had

significantly better outcomes than completing participants without an ASD diagnosis.

A study into the effect of DBT in ASD patients with suicidality and/ or self-destructive

behaviour is currently underway, however, no results have been published [25].

As of 2013,

Asperger’s is now considered part of the autism spectrum and is no longer

diagnosed as a separate condition [26].

5 What is the general application of DBT?

DBT is composed of four elements that the individual and therapist usual y work on over a

year or more [1, 27]:

• Individual DBT therapy, which uses techniques like cognitive restructure and

exposure to change behaviour and improve quality of life.

• Group therapy, which uses skil s training to teach patients how to respond wel to

difficult problems or situations.

• Phone calls, which focus on applying learned skil s to life outside of therapy.

• Weekly consultation meetings among the DBT therapists, which offer a means of

support for the therapists and to ensure they are fol owing the DBT treatment

model.

Some of the strategies and techniques that are used in DBT include:

Core Mindfulness

Page 206 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

One important benefit of DBT is the development of mindfulness skil s [28]. Mindfulness

helps to focus on the present or “live in the moment.” Mindfulness skil s help you slow

down and focus on using healthy coping skil s when you are in the midst of emotional pain.

The strategy can also help you stay calm and avoid engaging in automatic negative thought

patterns and impulsive behaviour [27, 28].

Distress Tolerance

Distress tolerance skills help patients to accept oneself and their current situation. There are

four techniques for handling a crisis [27]:

• Distraction

• Improving the moment

• Self-soothing

• Thinking of the pros and cons of not tolerating distress

Distress tolerance techniques help prepare patients for intense emotions and empower

them to cope with a more positive long-term outlook [1].

Interpersonal Effectiveness

Interpersonal effectiveness, at its most basic, refers to the ability to interact with others

[27]. It helps patients to become more assertive in a relationship (for example, expressing

your needs and be able to say "no") while stil keeping a relationship positive and healthy.

Principles include learning to listen and communicate more effectively, deal with

chal enging people, and respect yourself and others [27, 29].

Emotion Regulation

Emotion regulation lets an individual navigate powerful feelings in a more effective way. The

skills learnt will help to identify, name, and change emotions [30].

When an individual is able to recognize and cope with intense negative emotions (for

example, anger), it reduces emotional vulnerability and helps to enable more positive

emotional experiences.

Over the course of treatment, individuals will learn [1, 27]:

•

Acceptance and change: Learn strategies to accept and tolerate life circumstances,

emotions, and yourself. Develop skills that can help you make positive changes in

your behaviours and interactions with others.

•

Behavioural: Learn to analyse problems or destructive behaviour patterns and

replace them with more healthy and effective ones.

•

Cognitive: Focus on changing thoughts, beliefs, behaviours, and actions that are not

effective or helpful.

Page 207 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

•

Collaboration: Learn to communicate effectively and work together as a team

(therapist, group therapist, and psychiatrist).

•

Skill sets: Learn new skills to enhance your capabilities.

•

Support: Be encouraged to recognize your positive strengths and attributes and

develop and use them.

6 Available funding options

In most Australian states, DBT programs can be accessed through both the public and

private mental health system [31, 32].

6.1 Public services

Public DBT programs are free to people living in the catchment area of a hospital that offers

a program. A case manager, mental health professional or GP can assist with referral

options.

Depending on the hospital, there may be a waiting time to access the program. Some DBT

programs run continuously across the year, while others operate on a more specific

schedule.

6.2 Private services

Private DBT programs require payment. Prices will vary depending on the specific service

chosen. If you have private health insurance, check that it covers psychiatric admissions.

To join a private DBT program, a psychiatrist from the specific hospital or clinic can provide a

referral.

7 Please provide a list of possible experts in DBT in

Australia

Dr Amanda Johnson (Clinical Psychologist)

Dr Johnson have been trained at Monash University and in the United States at the

University of Denver. Her doctoral thesis evaluated a standard DBT program in a community

health setting over a three year period. She has been involved in the development of several

DBT programs in the public and private sectors in Victoria and providing specialist DBT

supervision, consultation and training.

Email xxxx@xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx.xxx.xx

Ph 03 9530 9777

Dr. Julie King (Clinical Psychologist)

Page 208 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

Dr Julie King is a clinical psychologist who offers a range of psychological services. Her

doctorate examined the experience of intel ectual giftedness as asynchrony. She has worked

with the development of youth and antidepressant protocols in general practice. With a

passion for increasing resiliency and coping, Julie is intensively trained in DBT for Borderline

Personality Disorder.

Mob: 0414 432 623

Email: xxxxxxxxxx@xxxxx.xxx

Dr. Lillian Nejad (Clinical Psychologist)

Lillian Nejad, PhD, is a registered and endorsed clinical psychologist with over 20 years of

experience in the assessment and treatment of adults with mild to severe psychological

issues and disorders. She has applied her extensive knowledge and experience in a variety of

settings as a Monash University Lecturer and Clinical Supervisor, as a Senior Psychologist in

public mental health settings, in private practice, and within community and corporate

organisations.

Contact can be made through her website. https://www.drlilliannejad.com/letstalk

Dr. Peter King (Mental Health Nurse; Individual Psychotherapist)

Peter provides education and program development in specialty areas that include

Borderline Personality Disorder, Dialectical Behaviour Therapy, Crisis Intervention,

Psychiatric Emergencies, Somatic Trauma Therapy and Mindfulness-based approaches in

mental health care. Peter has specialist training in CBT, DBT, Somatic Trauma Therapy,

Mindfulness and his Ph.D. explores treatments for individuals with Borderline Personality

Disorder and clinicians’ training needs

xxxxx@xxxx.xxx

Australian DBT Institute: 07 56473438

Page 209 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

8 References

1.

May JM, Richardi TM, Barth KS. Dialectical behavior therapy as treatment for borderline

personality disorder. Mental Health Clinician [Internet]. 2016; 6(2):[62-7 pp.]. Available from:

https://doi.org/10.9740/mhc.2016.03.62.

2.

Chapman AL. Dialectical behavior therapy: current indications and unique elements.

Psychiatry (Edgmont) [Internet]. 2006; 3(9):[62-8 pp.]. Available from:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2963469/.

3.

Lieb K, Stoffers J. AS14-01 - Comparative Efficacy of Evidence Based Psychotherapies in the

Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. European Psychiatry [Internet]. 2012; 27(S1):[1- pp.].

Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/article/as1401-comparative-efficacy-of-evidence-

based-psychotherapies-in-the-treatment-of-borderline-personality-

disorder/F16CED8DCA3E936794AF740F9BD33125.

4.

Storebø OJ, Stoffers-Winterling JM, Völ m BA, Kongerslev MT, Mattivi JT, Jørgensen MS, et

al. Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database of

Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2020; (5). Available from:

https://doi.org//10.1002/14651858.CD012955.pub2.

5.

Panos PT, Jackson JW, Hasan O, Panos A. Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review Assessing the

Efficacy of Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT). Research on Social Work Practice [Internet]. 2013

2014/03/01; 24(2):[213-23 pp.]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731513503047.

6.

Kliem S, Kröger C, Kosfelder J. Dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality

disorder: A meta-analysis using mixed-effects modeling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical

Psychology [Internet]. 2010; 78(6):[936-51 pp.]. Available from: 10.1037/a0021015.

7.

DeCou CR, Comtois KA, Landes SJ. Dialectical Behavior Therapy Is Effective for the Treatment

of Suicidal Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. Behavior Therapy [Internet]. 2019 2019/01/01/; 50(1):[60-72

pp.]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pi /S0005789418300492.

8.

Harned MS, Korslund KE, Linehan MM. A pilot randomized controlled trial of Dialectical

Behavior Therapy with and without the Dialectical Behavior Therapy Prolonged Exposure protocol

for suicidal and self-injuring women with borderline personality disorder and PTSD. Behaviour

Research and Therapy [Internet]. 2014 2014/04/01/; 55:[7-17 pp.]. Available from:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0005796714000151.

9.

Bohus M, Kleindienst N, Hahn C, Mül er-Engelmann M, Ludäscher P, Steil R, et al. Dialectical

Behavior Therapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (DBT-PTSD) Compared With Cognitive Processing

Therapy (CPT) in Complex Presentations of PTSD in Women Survivors of Childhood Abuse: A

Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry [Internet]. 2020; 77(12):[1235-45 pp.]. Available from:

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.2148.

10.

van den Bosch LMC, Verheul R, Schippers GM, van den Brink W. Dialectical Behavior Therapy

of borderline patients with and without substance use problems: Implementation and long-term

effects. Addictive Behaviors [Internet]. 2002 2002/11/01/; 27(6):[911-23 pp.]. Available from:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306460302002939.

11.

Linehan MM, Dimeff LA, Reynolds SK, Comtois KA, Welch SS, Heagerty P, et al. Dialectical

behavior therapy versus comprehensive validation therapy plus 12-step for the treatment of opioid

dependent women meeting criteria for borderline personality disorder. Drug and Alcohol

Dependence [Internet]. 2002 2002/06/01/; 67(1):[13-26 pp.]. Available from:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S037687160200011X.

Page 210 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

12.

Lynch TR, Morse JQ, Mendelson T, Robins CJ. Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Depressed

Older Adults: A Randomized Pilot Study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry [Internet].

2003 2003/01/01/; 11(1):[33-45 pp.]. Available from:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S106474811261238X.

13.

Lynch TR. Treatment of elderly depression with personality disorder comorbidity using

dialectical behavior therapy. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice [Internet]. 2000 2000/09/01/;

7(4):[468-77 pp.]. Available from:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1077722900800589.

14.

Telch CF, Agras, W. S., & Linehan, M. M. Dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating

disorder2001; 69:[1061-5 pp.]. Available from: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2001-05666-020.

15.

Foote B, Van Orden K. Adapting Dialectical Behavior Therapy for the Treatment of

Dissociative Identity Disorder. American Journal of Psychotherapy [Internet]. 2016 //; 70(4):[343-64

pp.]. Available from:

https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/afap/ajp/2016/00000070/00000004/art00001.

16.

Ross CA, Ferrell L, Schroeder E. Co-Occurrence of Dissociative Identity Disorder and

Borderline Personality Disorder. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation [Internet]. 2014 2014/01/01;

15(1):[79-90 pp.]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2013.834861.

17.

Ross CA. A Proposed Trial of Dialectical Behavior Therapy and Trauma Model Therapy.

Psychological Reports [Internet]. 2005 2005/06/01; 96(3_suppl):[901-11 pp.]. Available from:

https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.96.3c.901-911.

18.

Brand BL, Loewenstein RJ, Spiegel D. Dispelling Myths About Dissociative Identity Disorder

Treatment: An Empirically Based Approach. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes

[Internet]. 2014 2014/06/01; 77(2):[169-89 pp.]. Available from:

https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2014.77.2.169.

19.

Brand BL, Classen CC, McNary SW, Zaveri P. A Review of Dissociative Disorders Treatment

Studies. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease [Internet]. 2009; 197(9). Available from:

https://journals.lww.com/jonmd/Fulltext/2009/09000/A Review of Dissociative Disorders Treatm

ent.2.aspx.

20.

International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation. Guidelines for treating

dissociative identity disorder in adults, third revision. J Trauma Dissociation [Internet]. 2011;

12(2):[115-87 pp.].

21.

Dudas RB, Lovejoy C, Cassidy S, Allison C, Smith P, Baron-Cohen S. The overlap between

autistic spectrum conditions and borderline personality disorder. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2017;

12(9):[e0184447 p.]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184447.

22.

Hartmann K, Urbano M, Manser K, Okwara L. Modified Dialectical Behavior Therapy to

Improve Emotion Regulation in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Available from:

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kathrin-

Hartmann/publication/317049395 In Autism Spectrum Disorders Modified Dialectical Behavior

Therapy to Improve Emotion Regulation in Autism Spectrum Disorders/links/59230d200f7e9b9

97945b670/In-Autism-Spectrum-Disorders-Modified-Dialectical-Behavior-Therapy-to-Improve-

Emotion-Regulation-in-Autism-Spectrum-Disorders.pdf.

23.

Shkedy G, Shkedy D, Sandoval-Norton AH. Treating self-injurious behaviors in autism

spectrum disorder. Cogent Psychology [Internet]. 2019 2019/01/01; 6(1):[1682766 p.]. Available

from: https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2019.1682766.

24.

Cornwall PL, Simpson S, Gibbs C, Morfee V. Evaluation of radically open dialectical behaviour

therapy in an adult community mental health team: effectiveness in people with autism spectrum

disorders. BJPsych Bul etin [Internet]. 2021; 45(3):[146-53 pp.]. Available from:

https://www.cambridge.org/core/article/evaluation-of-radically-open-dialectical-behaviour-therapy-

in-an-adult-community-mental-health-team-effectiveness-in-people-with-autism-spectrum-

disorders/2BC4B0CF8DDBFCDCFD2CD9089545B4D8.

Page 211 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

25.

Huntjens A, van den Bosch LMCW, Sizoo B, Kerkhof A, Huibers MJH, van der Gaag M. The

effect of dialectical behaviour therapy in autism spectrum patients with suicidality and/ or self-

destructive behaviour (DIASS): study protocol for a multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMC

Psychiatry [Internet]. 2020 2020/03/17; 20(1):[127 p.]. Available from:

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02531-1.

26.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders

(DSM-5®): American Psychiatric Pub; 2013.

27.

Schimelpfening N. What Is Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)? 2021 [Available from:

https://www.verywellmind.com/dialectical-behavior-therapy-1067402.

28.

Feliu-Soler A, Pascual JC, Borràs X, Portella MJ, Martín-Blanco A, Armario A, et al. Effects of

Dialectical Behaviour Therapy-Mindfulness Training on Emotional Reactivity in Borderline Personality

Disorder: Preliminary Results. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy [Internet]. 2014 2014/07/01;

21(4):[363-70 pp.]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1837.

29.

Lenz AS, Del Conte G, Hollenbaugh KM, Callendar K. Emotional Regulation and Interpersonal

Effectiveness as Mechanisms of Change for Treatment Outcomes Within a DBT Program for

Adolescents. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation [Internet]. 2016 2016/12/01; 7(2):[73-85

pp.]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/2150137816642439.

30.

Goodman M, Carpenter D, Tang CY, Goldstein KE, Avedon J, Fernandez N, et al. Dialectical

behavior therapy alters emotion regulation and amygdala activity in patients with borderline

personality disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research [Internet]. 2014 2014/10/01/; 57:[108-16 pp.].

Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022395614001952.

31.

SANE Australia. Fact Sheet: Dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) 2017 [Available from:

https://www.sane.org/information-stories/facts-and-guides/dialectical-behaviour-therapy-dbt.

32.

Australian Borderline Personality Foundation Limited. How to access treatment ND

[Available from: https://bpdfoundation.org.au/how-to-access-treatment.php.

Page 212 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

DOCUMENT 22

1. Research – Exposure Therapy for PTSD

Exposure Therapy - Data on its efficacy in treating PTSD. Is it the

optimal treatment? Comparative data on the efficacy of other evidence

Brief

based treatments for PTSD, specifically trauma-focussed cognitive

behavioural therapy (CBT) and eye movement desensitisation and

reprocessing (EMDR).

Date

16/08/21

Requester(s) Jenni s22(1)(a)(ii)

- irreleva - Senior Technical Advisor (TAB/AAT)

Researcher

Maddie s22(1)(a)(ii) (

- irrele

and

Aaron s22(1)(a)(ii)

)

- irrelevant m

Cleared

Please note:

The research and literature reviews col ated by our TAB Research Team are not to be shared external to the

Branch. These are for internal TAB use only and are intended to assist our advisors with their reasonable and

necessary decision-making.

Delegates have access to a wide variety of comprehensive guidance material. If Delegates require further

information on access or planning matters they are to call the TAPS line for advice.

The Research Team are unable to ensure that the information listed below provides an accurate & up-to-date

snapshot of these matters.

The content of this document is OFFICIAL.

1 Contents

2 Summary ....................................................................................................................... 2

3 What is Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)? .......................................................... 2

4 Clinical Presentation ...................................................................................................... 3

5 Therapeutic treatment options ........................................................................................ 4

5.1

Exposure ................................................................................................................ 4

6 Efficacy of PTSD therapies ............................................................................................ 4

7 References .................................................................................................................... 5

Page 213 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

2 Summary

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a mental health condition that can develop in

response to exposure to an event that threatens or is perceived to threaten a person’s life or

safety [1, 13]. This can include a serious accident, natural disaster or sexual assault.

People with PTSD can have intense intrusive thoughts such as flashbacks or distressing

dreams related to their traumatic experience lasting for months or years. PTSD is associated

with significant impacts to functioning and quality of life.

Trauma Focused Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (TF-CBT) is well-establish as an acute

treatment for PTSD. Several variants of TF-CBT are strongly recommended treatment

options. These include prolonged exposure therapy, cognitive therapy, cognitive processing

therapy and Eye Movement Desensitisation Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy.

Prolonged Exposure therapy or variants of TF-CBT that have a component of exposure are

preferred on slight weight of evidence for long term symptom reduction. Prolonged Exposure

therapy has been shown to be a highly effective method for reducing PTSD symptoms in

both the short-term and long-term.

3 What is Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder?

PTSD is a mental health condition that can develop in response to exposure to an event that

threatens or is perceived to threaten a person’s life or safety [1, 13].

PTSD can present in different ways but often involves intense intrusive thoughts and feelings

related to the traumatic experience. This can include vivid flashbacks, distressing dreams, or

repeated involuntary memories of the trauma. People with PTSD often avoid people, places

or situations which remind them of the traumatic event. PTSD also results in alterations to

cognition and mood such as memory loss or a persistent negative emotional state. It can

also cause other symptoms such as irritable behaviour, hypervigilance and issues with

concentration [1].

Symptoms usually appear within the first 3 months from exposure to trauma, however a

person may not experience symptoms until years after the traumatic event occurred.

Duration of the symptoms varies, with half of adults recovering within 3 months of developing

symptoms, but some experiencing symptoms for more than 50 years. The severity of

symptoms can vary over time. Many people experience more symptoms during stressful

periods or when they are exposed to reminders of their trauma [1].

PTSD is associated with significant impacts to functioning and quality of life. It can affect

relationships with friends and family, performance at work and can result in a reduction in

engagement in activities a person previously found rewarding [2].

PTSD has an estimated lifetime prevalence of 1.3% - 12.2% depending on social

background and country of residence [3]. Higher rates of PTSD have been documented

among women, younger people, and people who are socially disadvantaged [4]. People in

occupations that are more likely to expose them to traumatic events (for example,

emergency services, healthcare works and military personnel) are more likely to develop

PTSD [3, 5].

More than 50% of people with PTSD also have other mental health disorders, most

commonly depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, or substance use disorders [6].

Page 214 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

4 Clinical Presentation

The first characteristic of PTSD is that the person has witnessed or experienced a major

traumatic event [1]. This includes:

• directly experiencing the traumatic event(s)

• witnessing the traumatic event(s) in person

• learning about the traumatic event(s) which occurred to a close family member or

friend

• experiencing repeated exposure to details of traumatic event(s) (for example police

officers repeatedly exposed to details of child abuse).

Secondly, the person will have symptoms from each of the four PTSD symptom categories,

with the symptoms lasting for at least one month [1].

1.

Intrusion: at least one of the following symptoms

• Intrusive distressing memories

• Recurrent distressing dreams

• Flashbacks of the traumatic event

• Intense or prolonged psychological distress at exposure to reminders of the

trauma

• Physiological reactions to cues resembling an aspect of the traumatic event

2.

Avoidance: at least one of the following symptoms

• Avoiding places, people, objects and situations that may trigger distressing

memories

• Avoiding remembering or thinking about the traumatic event

3.

Alterations in cognition and mood: at least two of the following symptoms

• Inability to remember important aspects of the traumatic event

• Persistent negative thoughts about themselves or the world

• Distorted thoughts about the cause or consequences of the traumatic event

• Persistent negative emotional state

• Loss of interest in activities

• Persistent inability to experience positive emotions

• Feeling detached or estranged from other people

4.

Alterations in arousal and reactivity: at least two of the following symptoms

• Irritable behaviour and angry outbursts

• Reckless/self-destructive behaviour

• Hypervigilance

• Exaggerated startle response

• Issues with concentration

• Sleep disturbance

Individuals with PTSD can exhibit any combination of these symptoms.

Symptoms usually appear within the first 3 months from exposure to trauma, however a

person may not experience these symptoms until years after the traumatic event occurred.

Page 215 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

5 Therapeutic treatment options

TF-CBT is the generally recommended therapeutic treatment option for PTSD [4, 10].

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is a broad category of therapies used to treat mental

health disorders based on principles of learning and cognition. For people with PTSD, TF-

CBT is commonly used, which specifically addresses the impact of a traumatic event.

There are several variants of TF-CBT. However, there is a lack of consensus about what

therapies count as components or variants. TF-CBT can include development of coping

strategies, prolonged exposure therapy, narrative exposure therapy, cognitive processing

therapy, cognitive restructuring and EMDR [4, 7, 8, 14]. There is considerable overlap

between dif erent variants of cognitive behavioural therapy and they may be used together

[14]. While the variants of TF-CBT are often treated separately for research purposes, “they

all essentially comprise emotional processing of the traumatic memory and integration of

new corrective information” [4].

5.1

Use of exposure in TF-CBT Exposure is a therapeutic technique used in varieties of cognitive behavioural therapy. It is

used for many different mental health disorders, including PTSD. Prolonged exposure

therapy is a form of cognitive behavioural therapy which requires the patient to repeatedly

confront distressing stimuli associated with their trauma under the guidance of a mental

health professional, with the aim of extinguishing the conditioned emotional response to the

traumatic stimuli [7]. This can include exposure through imagination, by describing to the

patient scenes or mental imagery related to the traumatic event, or exposure to real-life

stimuli associated with the traumatic event. Prolonged exposure therapy is typically

conducted once or twice per week for 8-12 weeks in 60-90 minute sessions [7]. Some trials

show effectiveness of the treatment at 40-60 minute sessions or even 10-20 minute sessions

[4].

Other forms of TF-CBT such as Cognitive Processing Therapy and Cognitive Therapy focus

more on changing problematic beliefs and cognitive patterns [10].

Narrative exposure therapy is based on exposure therapy and testimony therapy. It involves

the

patient developing a chronological narrative of their entire life under the guidance of a

mental health professional with a focus on retelling their traumatic experience(s). Narrative

exposure therapy is tailored to experiences of war and torture [7].

There is some reason to also treat EMDR as a variant of exposure therapy [15], though it is

also often treated separately [7]. EDMR is a treatment for a variety of mental health

disorders including PTSD. In EDMR a patient is encouraged to momentarily think about their

trauma while the practitioner stimulates eye movements with the aim of desensitising the

patient to their trauma. In EDMR the patient may not have to return to the traumatic

experience for prolonged periods of time [9].

6 Efficacy of PTSD therapies

TF-CBT is well-establish as an acute treatment for PTSD. There is also evidence of long

term efficacy of TF-CBT. However, there is no unequivocal evidence for the preference of

any particular variant of TF-CBT as a frontline treatment option. Klein et al. find that

Page 216 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

exposure therapies have considerably larger effect sizes in the long term [10]. They

conclude:

Exposure-focused therapies, with the principal ingredient often being imaginal

exposure, demonstrated the most robust continued improvement following treatment,

yet it is meaningful that al of the broad range of trauma-focused treatments included

in the meta-analysis produced lasting gains. [10 §4]

Prolonged Exposure Therapy, Cognitive Therapy, and Cognitive Processing Therapy are all

strongly recommended by the Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of

Acute Stress Disorder, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Complex PTSD [8] and by the

American Psychological Association [16]. EMDR is strongly recommended by the Australian

Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Acute Stress Disorder, Posttraumatic Stress

Disorder and Complex PTSD [8] and conditionally recommended by the American

Psychological Association [16]. Exposure is a recommended component in most treatment

guidelines [4, 8, 16].

A meta-analysis of psychological treatments for adults with PTSD from 64 randomised

control trials determined that prolonged exposure therapy had the highest strength of

evidence for reducing PTSD symptoms [7]. The high efficacy of prolonged exposure therapy

has also been supported by further meta-analyses, with exposure-based treatments showing

stronger long-term improvement in PTSD symptoms relative to TF-CBT without exposure

[10].

There is stronger evidence supporting the efficacy of prolonged exposure therapy than

narrative exposure therapy [7]. Narrative exposure therapy is generally only recommended

for adults whose trauma is related to genocide, civil conflict, political detention, or

displacement [8].

Narrative exposure therapy and CBT-mixed therapies (therapies that used many

components of CBT) were found to have moderate evidence for reducing PTSD symptoms

[7].

A 2015 meta-analysis found then current research into EMDR to have low strength of

evidence for reducing PTSD symptoms but moderate strength of evidence for loss of PTSD

diagnosis and improving depression symptoms [7]. A 2018 meta-analysis found efficacy of

EMDR at the acute stage does not significantly differ from other variants of TF-CBT [10].

Despite the evidence supporting prolonged exposure therapy, there has been some

question as to whether exposure therapy in isolation is an ef ective treatment for PTSD.

Some argue that exposure therapy alone does not address all of the symptoms of PTSD and

should be used alongside other treatments [11]. Additionally, practitioners often fear high

drop-out rates due to the distressing nature of exposure-based therapies, however evidence

suggests that the drop-out rate for exposure therapies are no dif erent from other therapies

used to treat PTSD [12].

7 References

1.

American Psychiatric Association. Post raumatic Stress Disorder. In: Diagnostic and

statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition. Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric

Association. 2013. p. 271-280.

Page 217 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

2.

Forbes D, Nickerson A, Bryant RA, Creamer M, Silove D, McFarlane AC, Van Hooff

M, Phelps A, Felmingham KL, Malhi GS, Steel Z. The impact of post-traumatic stress disorder

symptomatology on quality of life: the sentinel experience of anger, hypervigilance and

restricted affect. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2019 Apr;53(4):336-49.

3.

Shalev A, Liberzon I, Marmar C. Post-traumatic stress disorder. New England Journal

of Medicine. 2017 Jun 22;376(25):2459-69.

4.

Bryant RA. Post‐traumatic stress disorder: a state‐of‐the‐art review of evidence and

challenges. World Psychiatry. 2019 Oct;18(3):259-69.

5.

Lee W, Lee YR, Yoon JH, Lee HJ, Kang MY. Occupational post-traumatic stress

disorder: an updated systematic review. BMC public health. 2020 Dec;20:1-2.

6.

Rytwinski NK, Scur MD, Feeny NC, Youngstrom EA. The co‐occurrence of major

depressive disorder among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta‐analysis.

Journal of traumatic stress. 2013 Jun;26(3):299-309.

7.

Cusack K, Jonas DE, Forneris CA, Wines C, Sonis J, Middleton JC, Feltner C,

Brownley KA, Olmsted KR, Greenblatt A, Weil A. Psychological treatments for adults with

posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical psychology

review. 2016 Feb 1;43:128-41.

8.

Phoenix Australia. Treatment Recommendations. In: Australian Guidelines for the

Prevention and Treatment of Acute Stress Disorder, Post raumatic Stress Disorder and

Complex PTSD [Internet]. Carlton (VIC ;2020 Jul.) Available from: Chapter-6.-Treatment-

recommendations.pdf (phoenixaustralia.org)

9.

De Haan KL, Lee CW, Fassbinder E, Van Es SM, Menninga S, Meewisse ML,

Rijkeboer M, Kousemaker M, Arntz A. Imagery rescripting and eye movement desensitisation

and reprocessing as treatment for adults with post-traumatic stress disorder from childhood

trauma: randomised clinical trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2020 Nov; 217(5):609-15.

10. Kline AC, Cooper AA, Rytwinksi NK, Feeny NC. Long-term efficacy of psychotherapy

for posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clinical

psychology review. 2018 Feb 1;59:30-40.

11. Markowitz S, Fanselow M. Exposure therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: factors

of limited success and possible alternative treatment. Brain sciences. 2020 Mar;10(3):167.

12. Paintain E, Cassidy S. First‐line therapy for post‐traumatic stress disorder: A

systematic review of cognitive behavioural therapy and psychodynamic approaches.

Counselling and psychotherapy research. 2018 Sep;18(3):237-50.

13.

Australian Government Australian Institute of Health and Welfare,

Australia's Health:

Glossary, [website], https:/ www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/australias-health/australias-health-

snapshots/glossary, (accessed 31 August 2021).

14.

Institute of Medicine 2008. Evidence and Conclusions: Psychotherapy. In, Treatment

of Post raumatic Stress Disorder: An Assessment of the Evidence. Washington, DC: The

National Academies Press.

Page 218 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

15.

Society of Clinical Psychology,

American Psychological Association Division 12,

[website], https://div12.org/treatment/eye-movement-desensitization-and-reprocessing-for-

post-traumatic-stress-disorder, (accessed 31 August 2021).

16.

American Psychological Association, Clinical Practice Guideline for the treatment of

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, [website], https://www.apa.org/ptsd-

guideline/treatments/index, (accessed 31 August 2021).

Page 219 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

DOCUMENT 23

Ratios of support

The content of this document is OFFICIAL.

Please note:

The research and literature reviews collated by our TAB Research Team are not to be

shared external to the Branch. These are for internal TAB use only and are intended to

assist our advisors with their reasonable and necessary decision-making.

Delegates have access to a wide variety of comprehensive guidance material. If

Delegates require further information on access or planning matters they are to call the

TAPS line for advice.

The Research Team are unable to ensure that the information listed below provides an

accurate & up-to-date snapshot of these matters.

Research question: Is there research (national and international) available that can inform

best practice in applying Ratios of Support to participant care in group programs and

supported employment? Are there guidelines available in other insurance type schemes

(national and international)?

Date: 14/12/2021

Requestor: Tiffany s22(1)(a)(ii)

- irre

Request endorsed by (EL1): Jane s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelev

Cleared by: Illya s22(1)(a)(ii) - irreleva

1. Contents

Ratios of support ........................................................................................................................ 1

1.

Contents ....................................................................................................................... 1

2.

Summary ...................................................................................................................... 2

3.

Assessment Tools ......................................................................................................... 2

4.

Guidelines ..................................................................................................................... 5

5.

Factors that can influence ratios of support .................................................................. 6

5.1 Manual Handling ........................................................................................................ 7

5.2 Behaviours of concern ............................................................................................... 8

6.

Social service analogues .............................................................................................. 8

7.

Appendix – Correspondence ........................................................................................ 9

Page 220 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

7.1

............................ 11

s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant material

7.2

............................ 11

7.3

............................ 12

7.4

............................ 13

7.5

............................ 16

7.6

............................ 17

7.7 NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission researchers ......................................... 17

8.

References ................................................................................................................. 19

9.

Version control ............................................................................................................ 21

2. Summary

Occupational Therapists (OT) use clinical judgement in determining ratios of support required

by clients for employment, community and social activities. OTs appeal to a wide variety of

considerations covering personal, environmental and institutional factors. No guidelines have

been developed by any organisation that offer clear guidance or rules for determining ratios of

support. Different assessment tools are used to inform clinical decision making depending on

the individual circumstances of the person requiring support.

3. Assessment Tools

Members of Occupational Therapy Australia (OTA) advised that the types of assessments they

use to assist with determining support ratios varies between participants. OTs employ their

clinical reasoning in determining which assessment tool wil provide the best information.

Some tools and strategies that were mentioned include:

• informal interview and history taking

• observing and analysing skil s of formal and informal supports

• Overt Behaviour Scale

• manual handling plans

• observing rosters and scheduling

• Care and Needs Scale

• Community Integration Questionnaire s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant material.

Previous research completed by the TAB Research Team in March 2021 identifies one

systematic review noting that only two assessment tools have been used for both

individualised support planning and resource allocation. They are the

Support Intensity Scale

Page 221 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

(SIS) and the

Instrument for the Classification and Assessment of Support Needs (I-

CAN) [1,2,3,4]. These two scales are the most widely researched support needs assessment

scales [2]. Both are in use in Australia [2,5]. I-CANS is based on the World Health

Organisation’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health. SIS uses the

American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities functioning model [2].

The SIS records frequency, duration and type of support required for specific activities. The

assessor rates activities according to the following scales:

FREQUENCY – How frequently is support needed for this activity?

0 = none or less than monthly

1 = at least once a month, but not once a week

2 = at least once a week, but not once a day

3 = at least once a day, but not once an hour

4 = hourly or more frequently

DAILY SUPPORT TIME – On a typical day when support in this area is needed, how

much time should be devoted?

0 = none

1 = less than 30 minutes

2 = 30 minutes to less than 2 hours

3 = 2 hours to less than 4 hours

4 = 4 hours or more

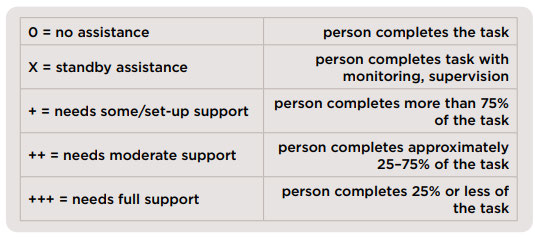

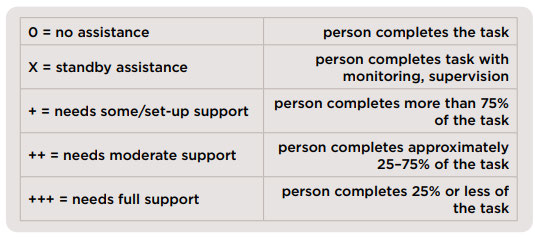

TYPES OF SUPPORT: What kind of support should be provided?

0 = none

1 = monitoring

2 = verbal/gestural prompting

3 = partial physical assistance

4 = full physical assistance [6].

The I-CAN records frequency and type of support required on a scale of 0 – 5 to then calculate

intensity of supports required:

FREQUENCY – how often support is needed

5 = Continuously

4 = Frequently

3 = Daily

Page 222 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

2 = Weekly

1 = Occasionally

0 = Never

TYPE – how much support is needed

5 = Pervasive

4 = Extensive

3 = Moderate

2 = Minor

1 = Managed

0 = Independent

COMBINED SUPPORT INTENSITY – sum of

Frequency and

Type scores

10 = Continuous / Pervasive

8 = Frequent/ Extensive

6 = Daily / Moderate

4 = Weekly / Minor

2 = Occasionally / Managed

0 = No support [7].

Paying particular attention to the

Type scores in both assessment scales, a suitably qualified

clinician may be able to interpret these scores in such a way as to suggest ratios of support or

at least suggest something about possible ratios of support. For example, a person with a SIS

Type score of 1 or 2 (monitoring, verbal/gestural prompting) for community access or

employment activities may thrive with a higher ratio environment compared to a person with a

SIS score of 4 (full physical assistance). Similarly, a person with an I-CAN

Type score of 1 or 2

(managed, minor) may benefit from group social activities with a shared support worker while a

person with a score of 4 or 5 (extensive, pervasive) may require direct individual support at a

1:1 or 2:1 ratio. However, the assessment tools do not specifically recommend ratios of

support and any conclusions about ratios would be significantly based on clinician’s expertise

or judgement.

It is also worth noting that these assessment tools do not determine support needs but are

based on the assessor’s observations of support needs. Both tools record support needs

based on the assessor’s understanding and then quantify and aggregate scores to indicate

overall support needs. In that sense, the contribution of these assessment tools to determining

ratios of support may be limited.

Page 223 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

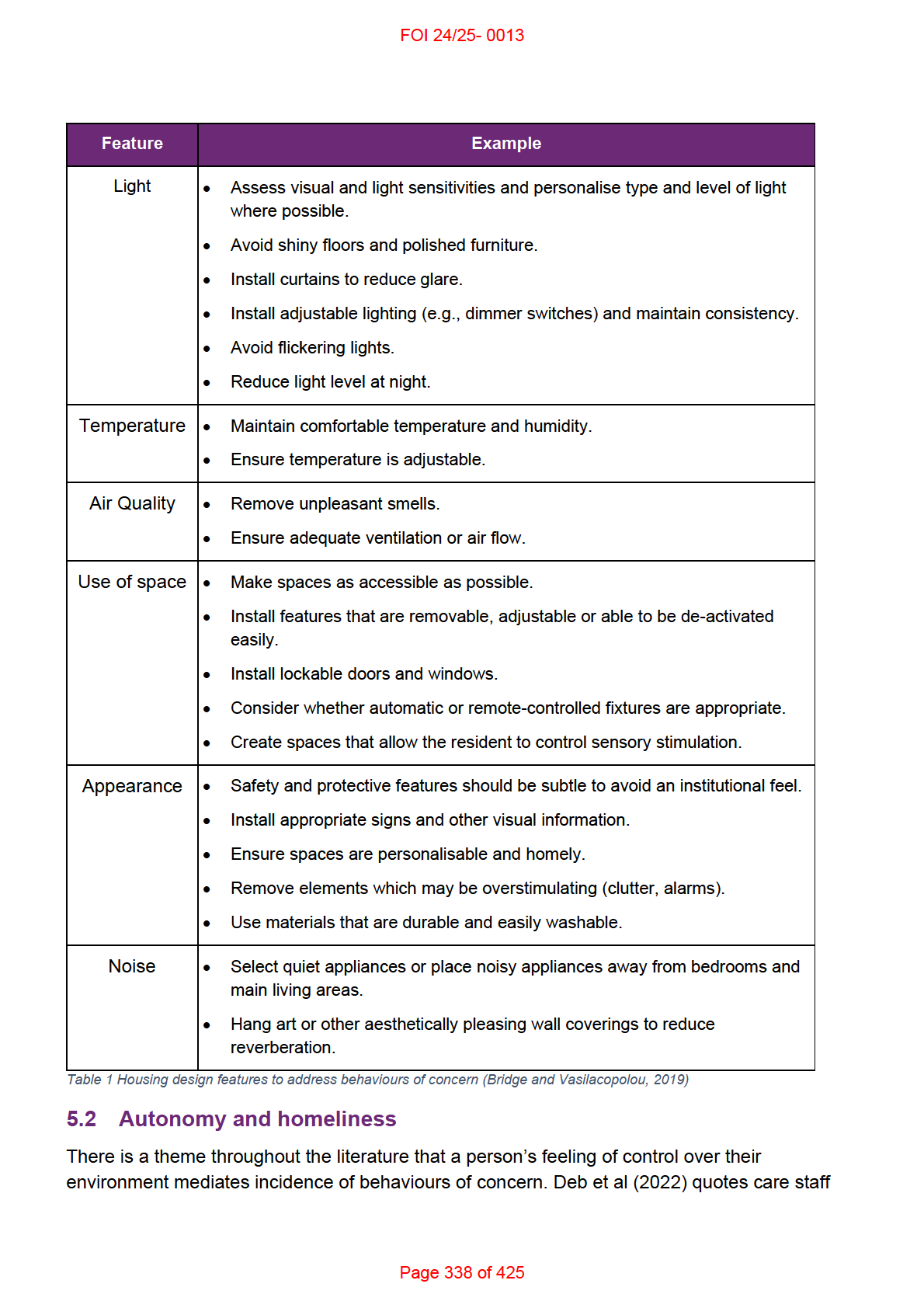

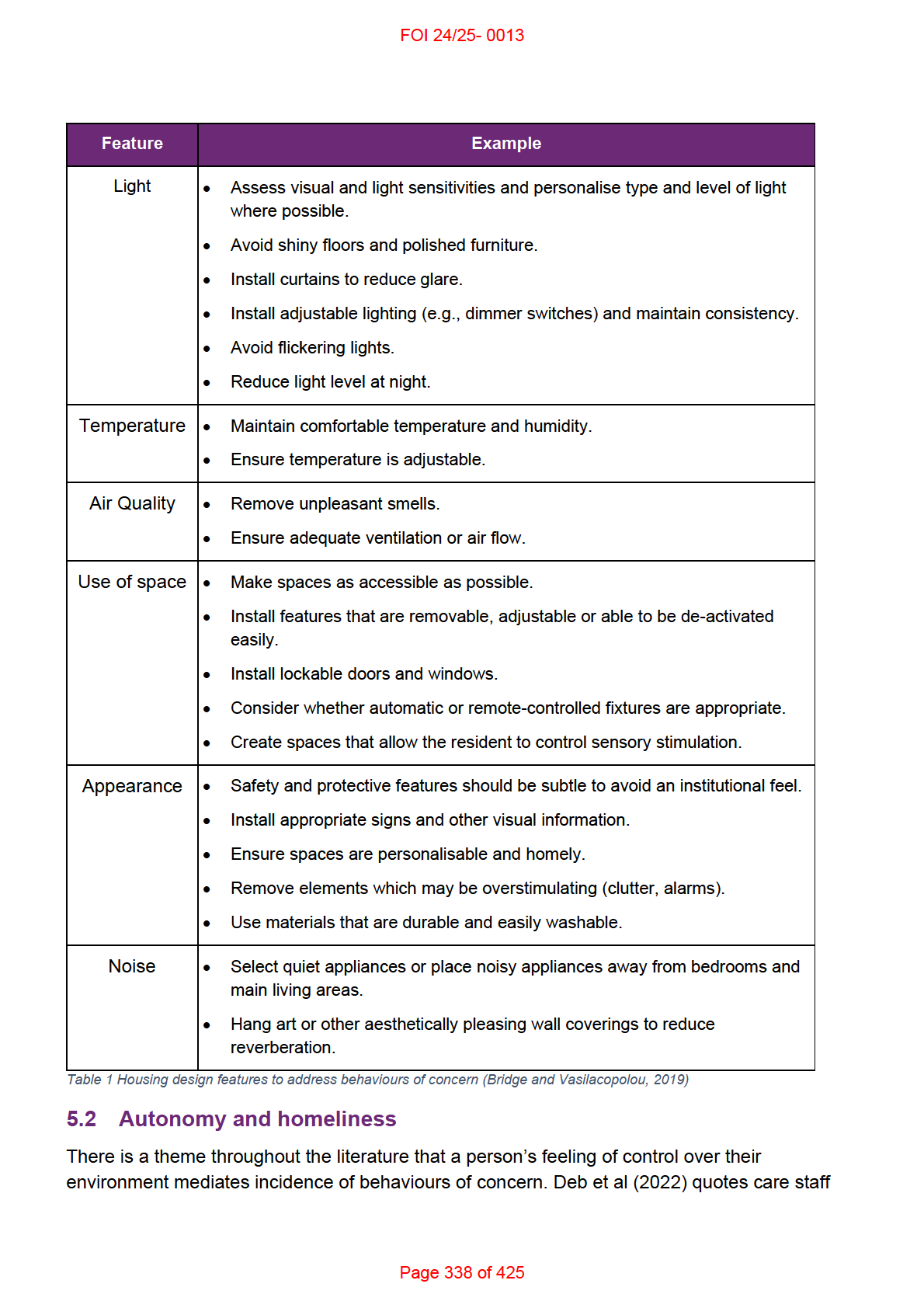

4. Guidelines

Previous research completed by the TAB Research Team in March 2021 states that there are

no available professional or governmental guidelines that can be used to support determining

personal care hours required for a range of tasks, disabilities and severity levels [1].

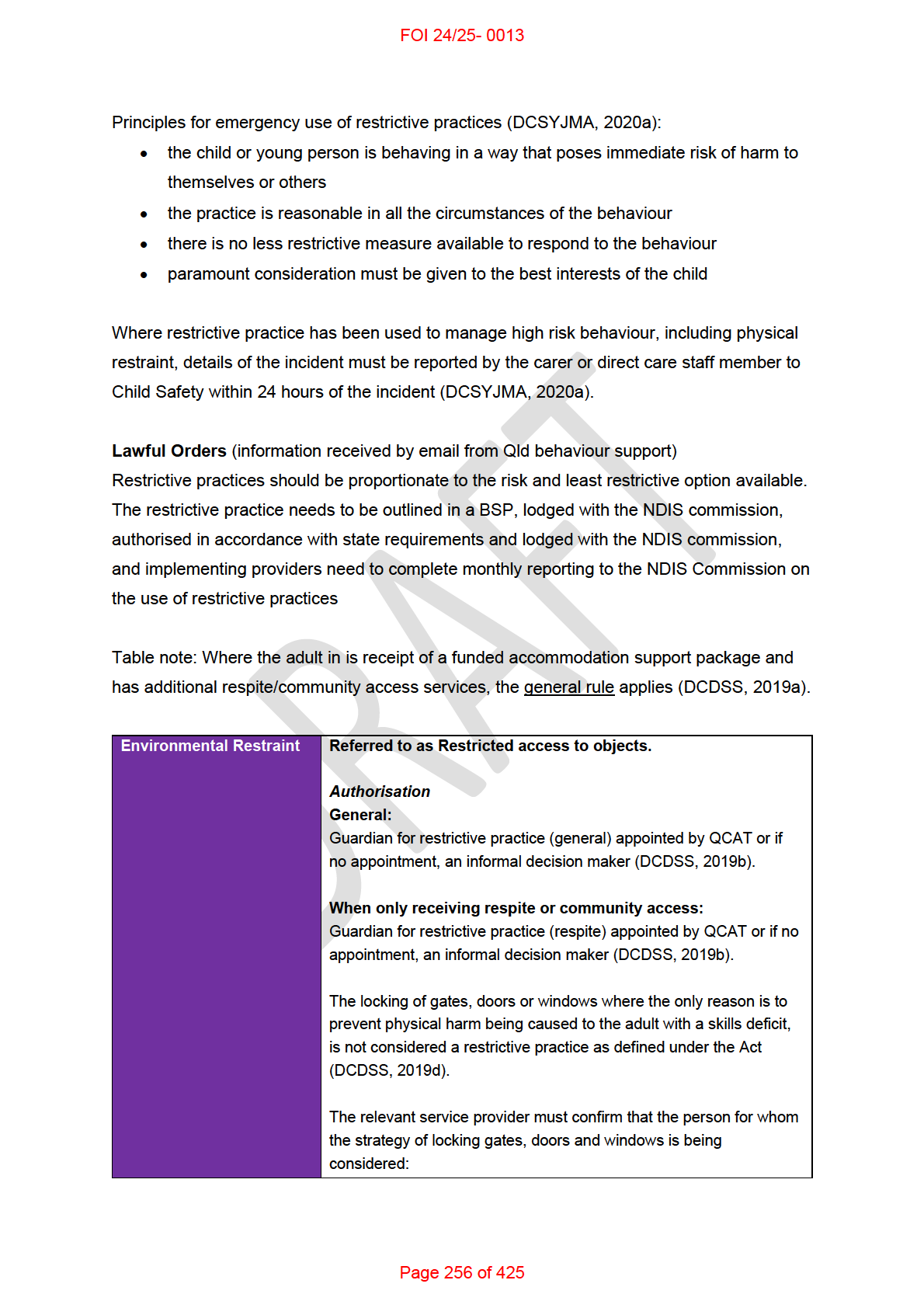

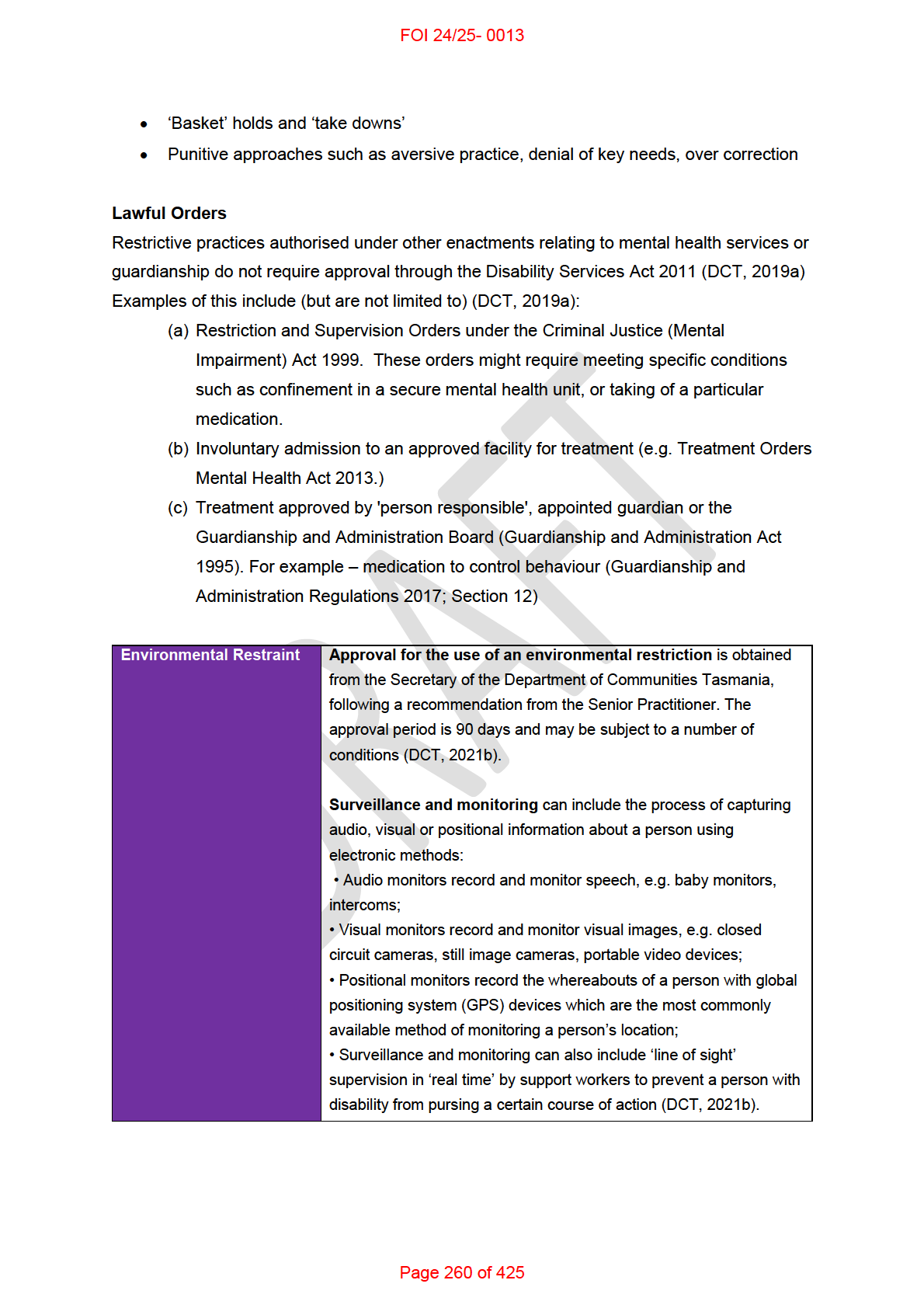

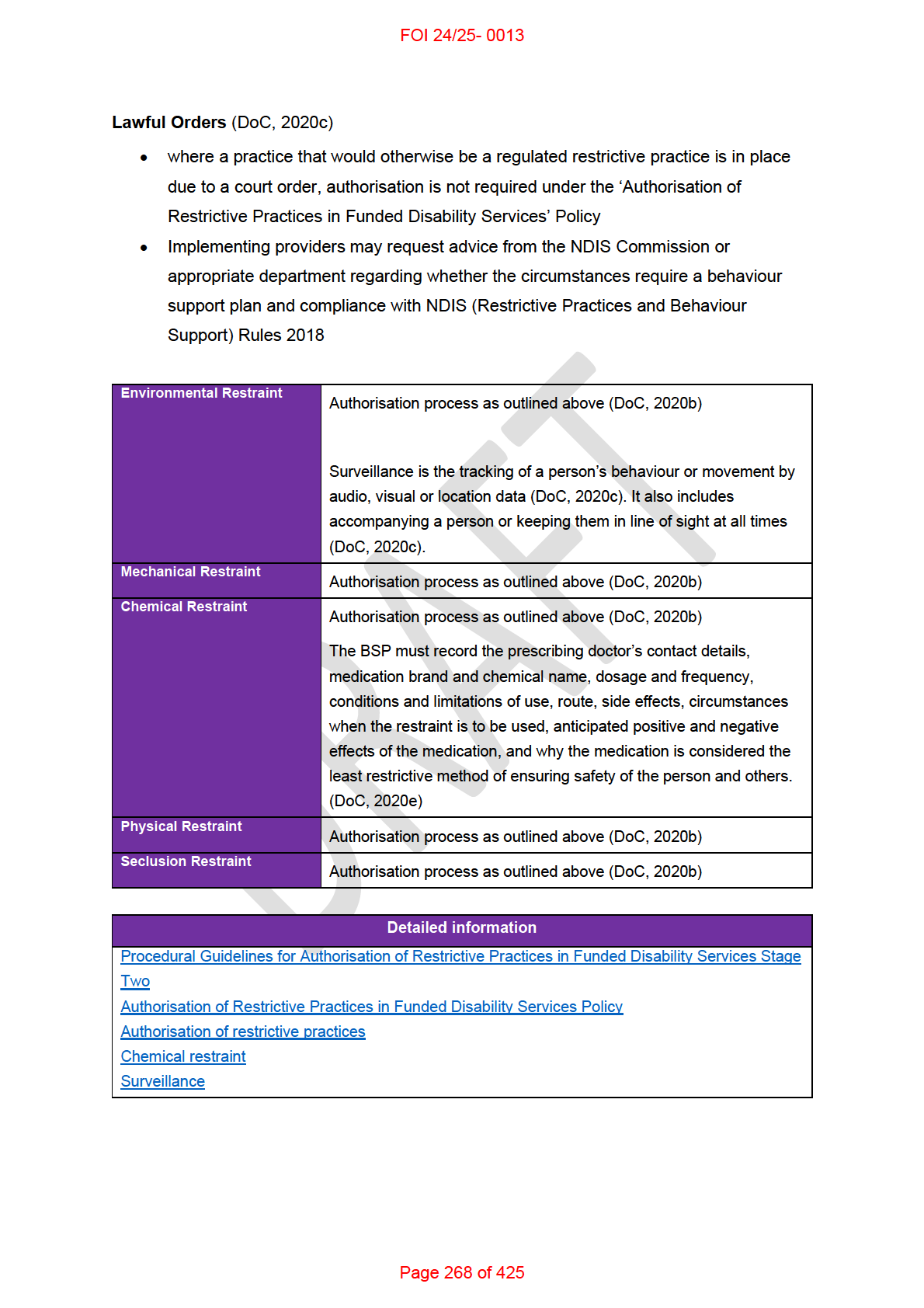

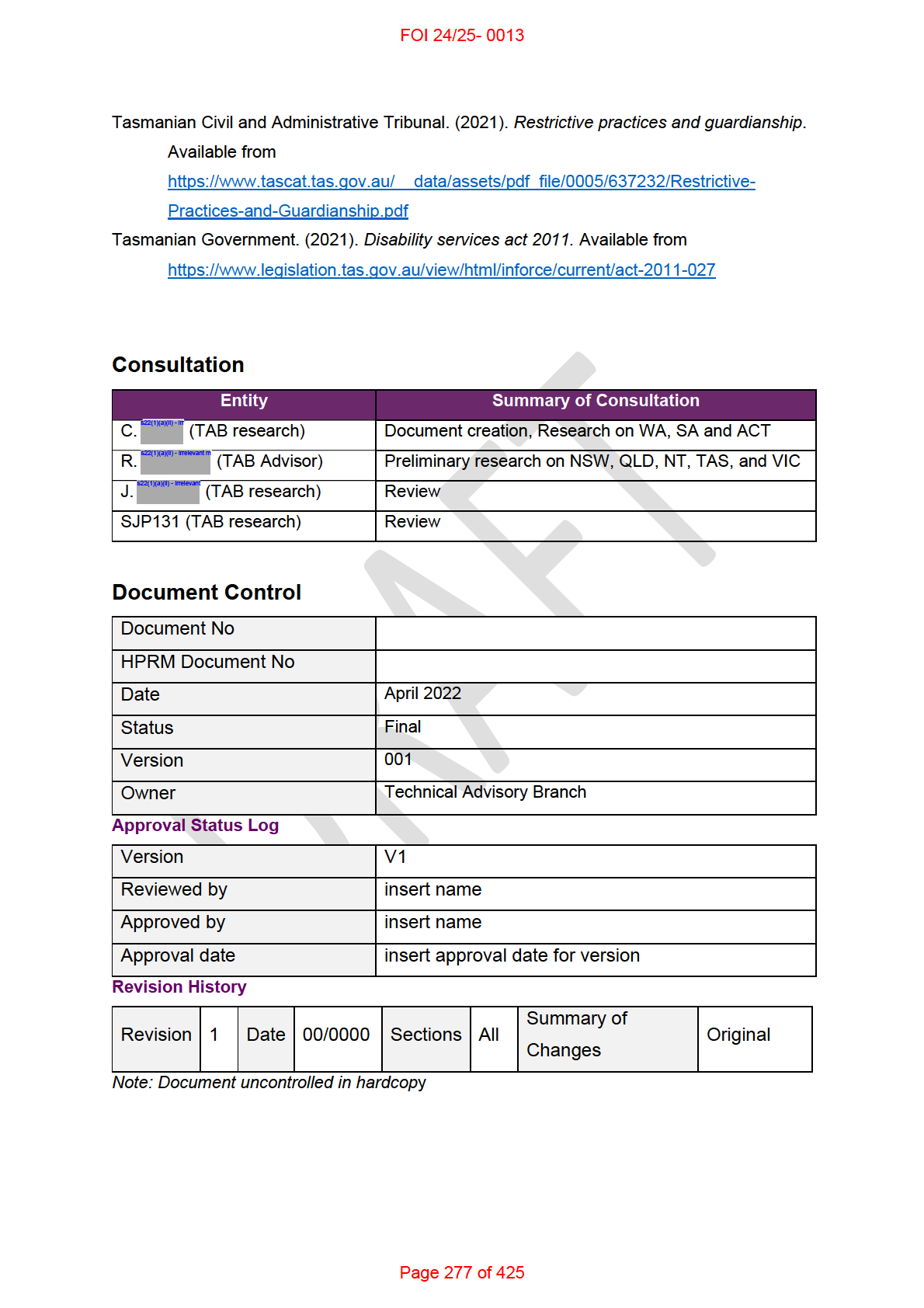

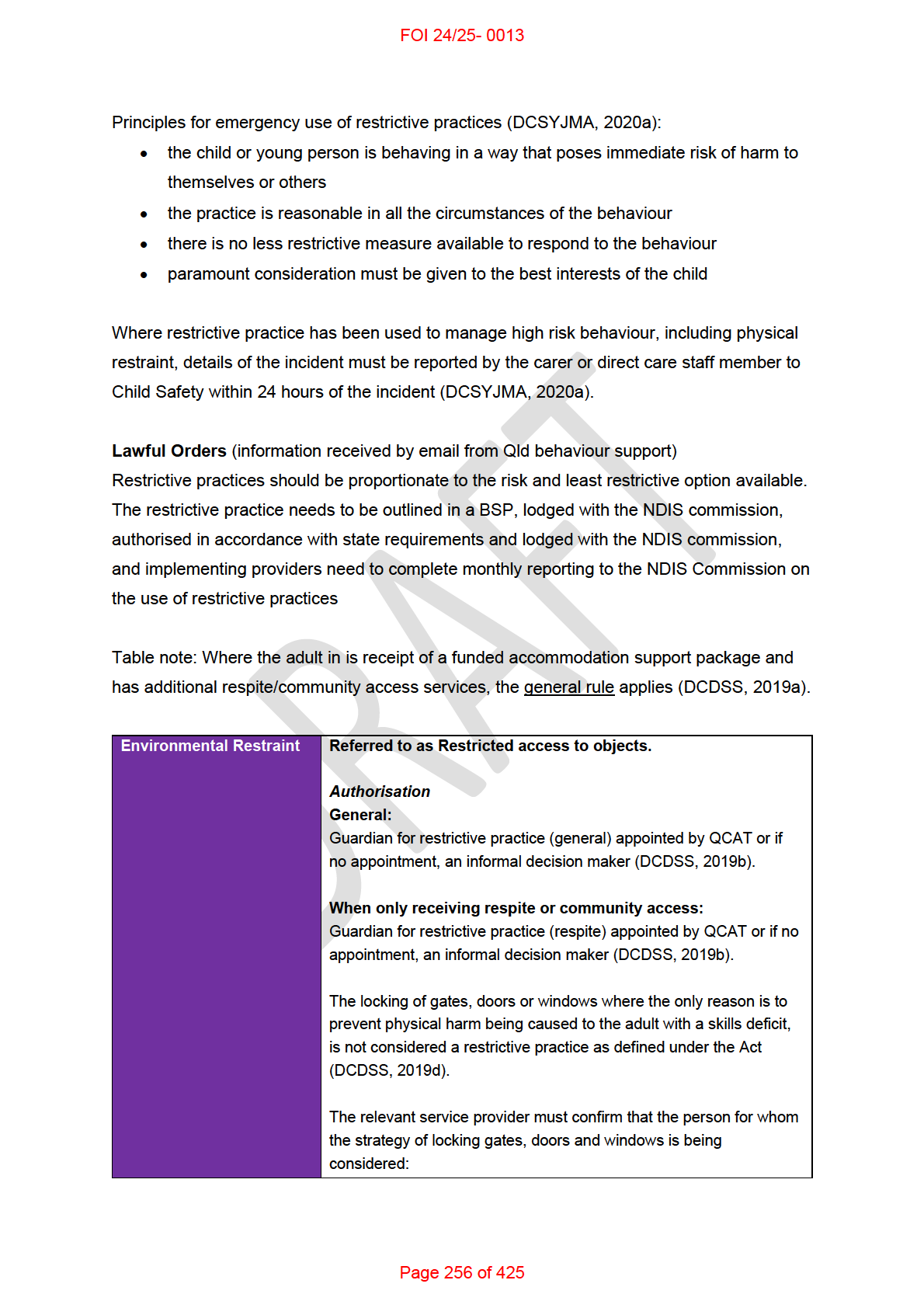

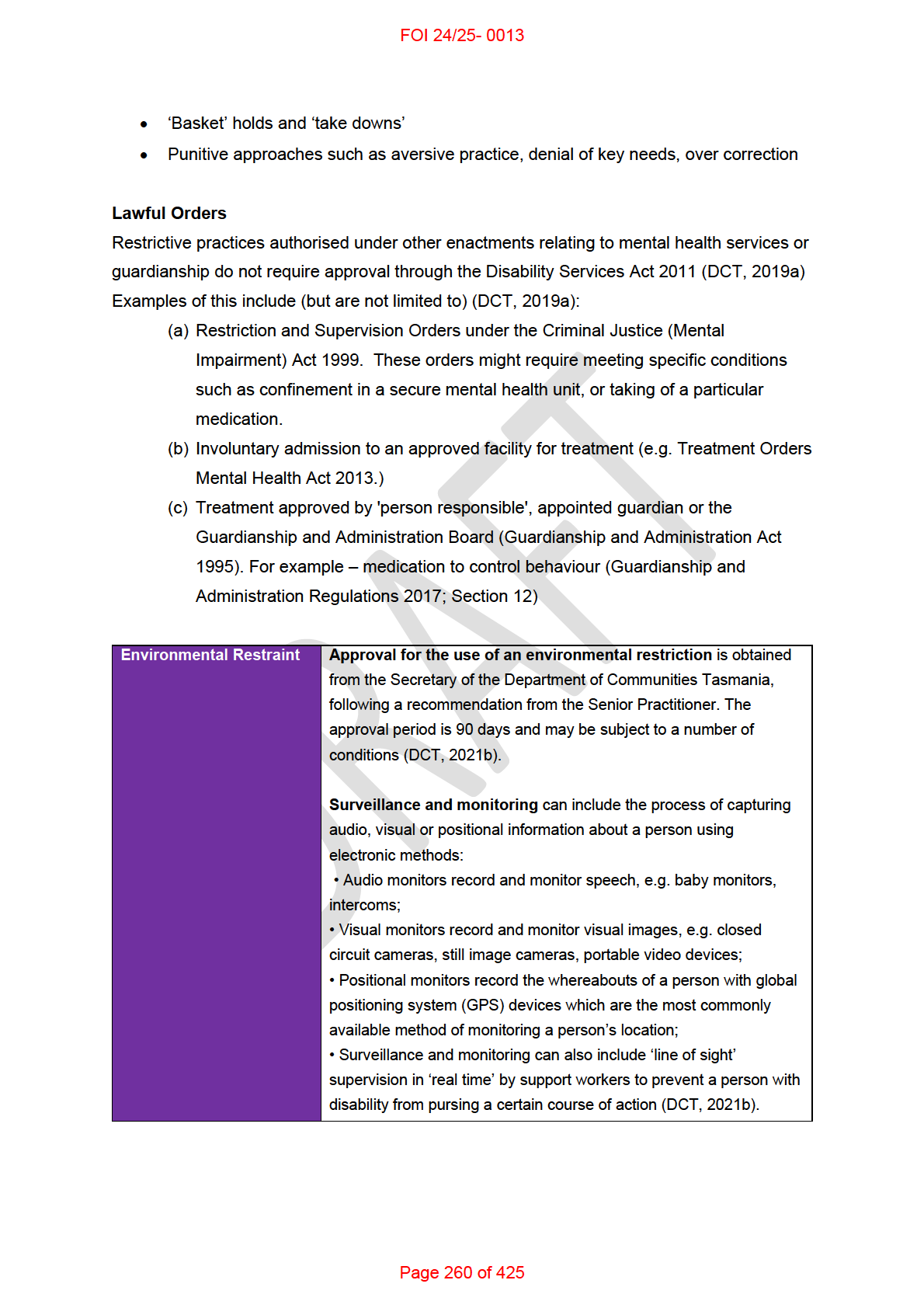

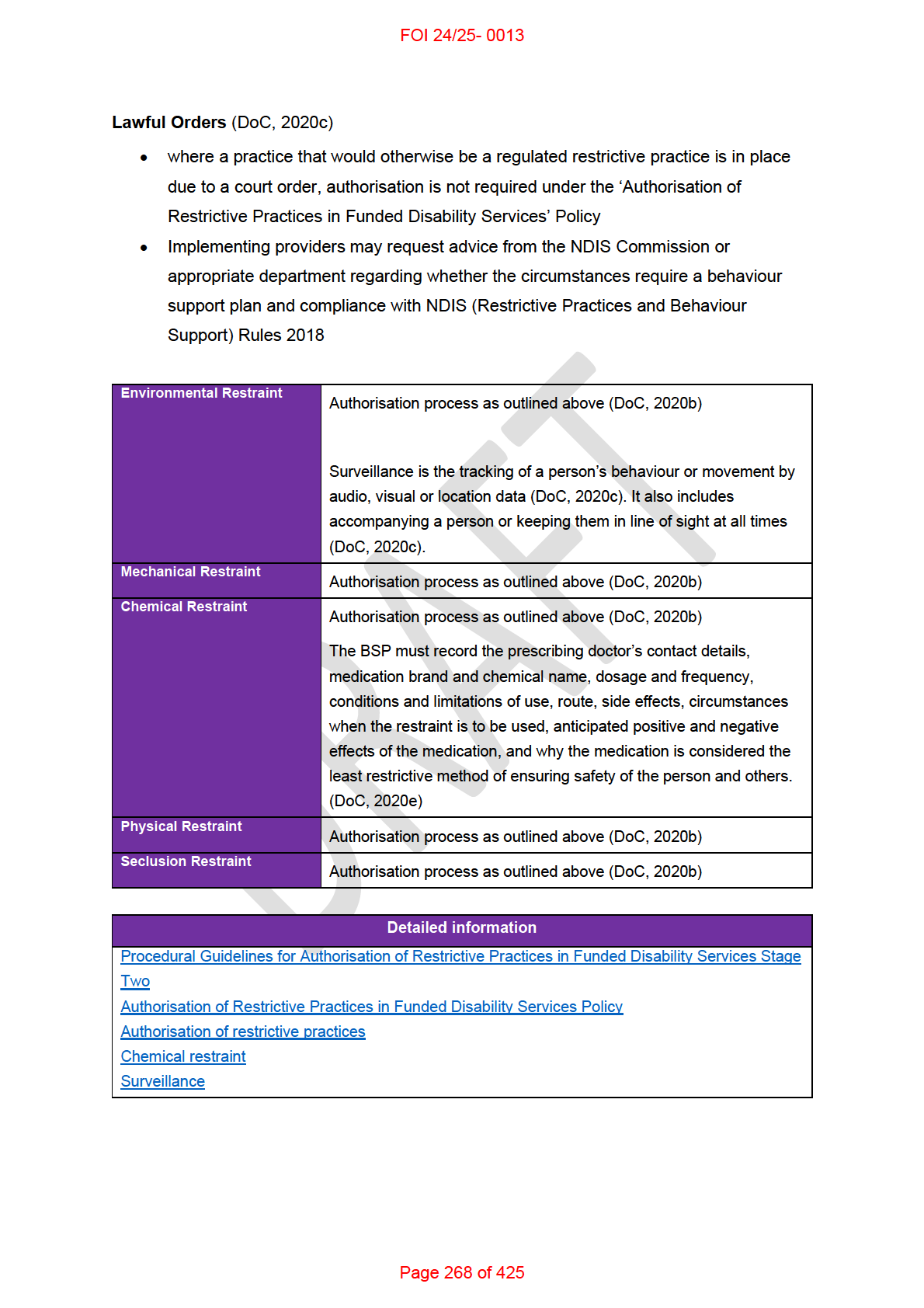

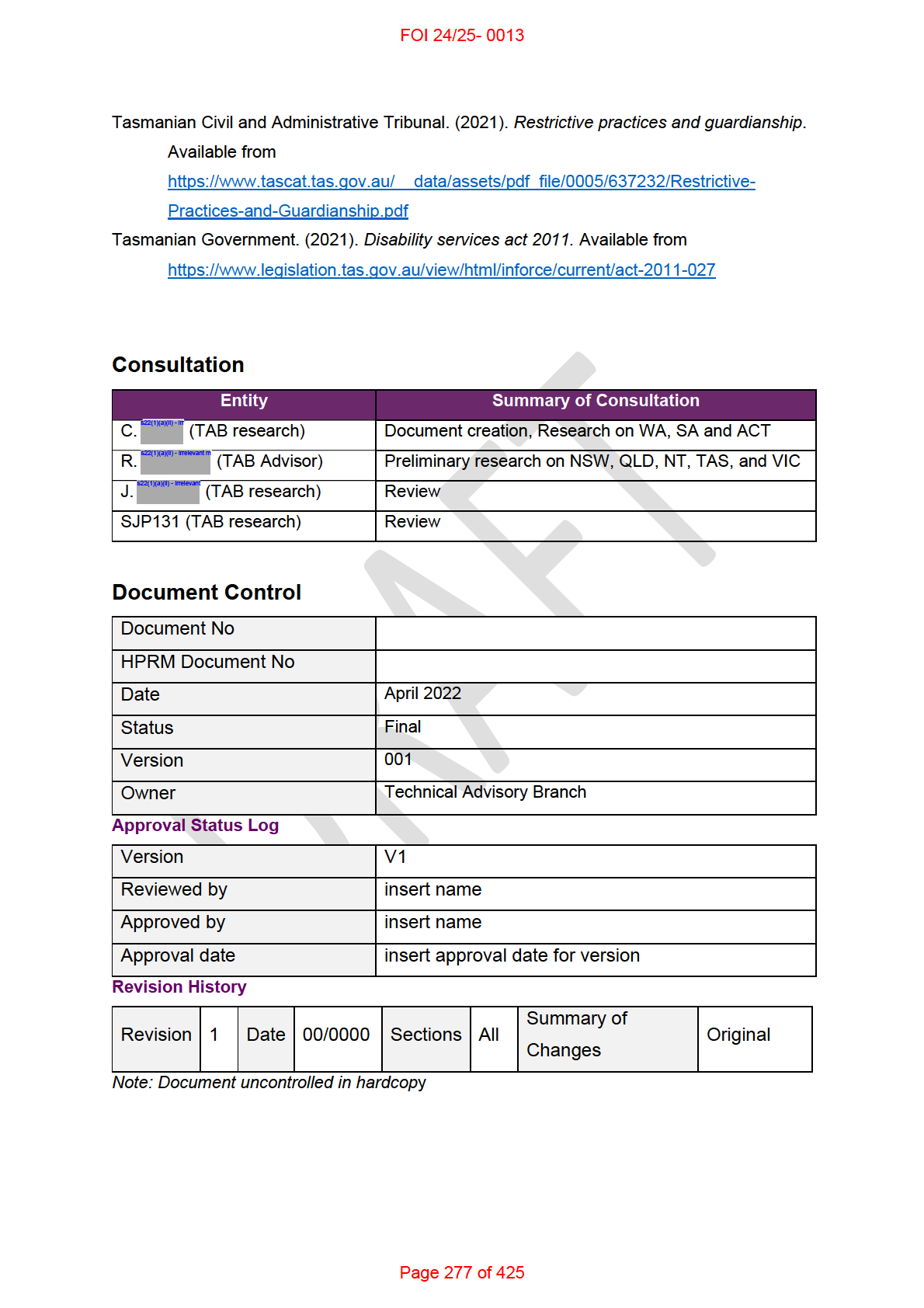

ICARE NSW has produced guidance relevant to people with Spinal Cord Injury. This

document estimates support needs for different levels of spinal cord injury. Considerable

clinical judgement is required to determine appropriate support hours. Ratios of support are

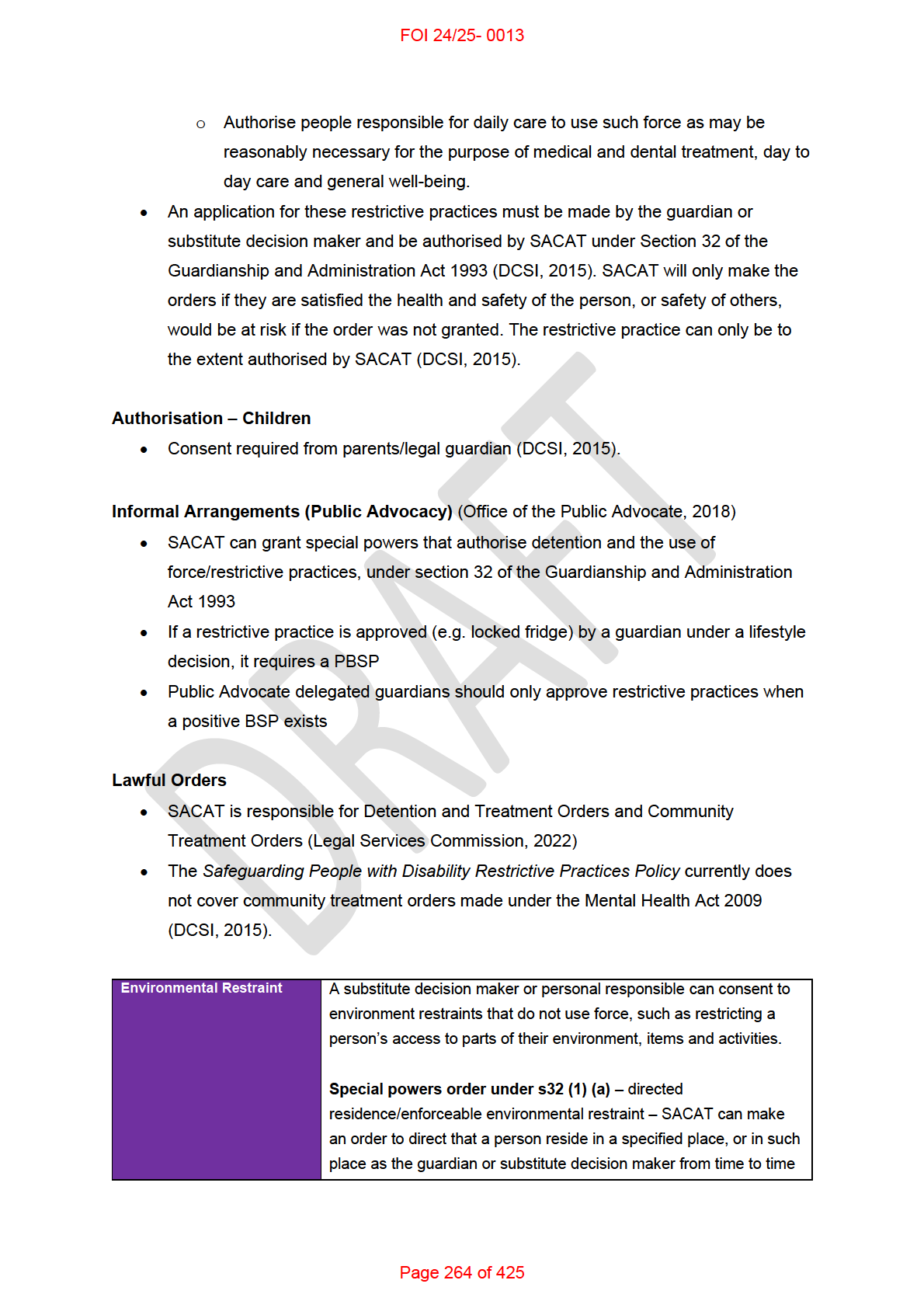

not explicitly mentioned. However, the estimates do appeal to the following scale:

[8]

As reasoned in 3. Assessment Tools, it may be possible to interpret this scale as implying

something about support ratios, however this would need to be done carefully and with

individual clinical justification.

I have not found any professional or governmental guidelines that could assist with

determining appropriate ratios of support for community access or group social activities. I

reached out to 13 professional Occupational Therapy organisations. I received replies from 6.

All 6 of the groups (s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant material

) confirmed that there were no overall guidelines and

that determination of support ratios occurs at a local or individual level [7. Appendix –

Correspondence].

Members of the s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant material reference group have advised:

Guidelines could be useful. However, information must be triangulated including

person’s own statement of performance, with observation, other clinical and care

information, client environment, and other relevant contextual factors. Any

inconsistencies need to be sorted out. Each client’s social and community participation

levels are different. What is reasonable and ordinary for their age, relationships, skil set

and social needs should be considered [s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant material].

s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant material , the Professional Practice Advisor from s22(1)(a)(ii) - i, als o referred me to a member of

their NDIS Reference group for further advice. s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant material, OT and founder/director of

s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant material , is in the process of developing and trialling a support measure aimed

Page 224 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

at informing NDIS planning decisions.

Discussions regarding this project are pending

s22(1)(a)(ii)

].

5. Factors that can influence ratios of support

s22(1)(a)(ii) - i me mbers advised the following factors can influence decisions about determining support

ratio:

• level of risk to self, others and property damage

• past incident reports

• manual handling risk plans

• self-report around comfort, confidence

• cognition

• safety risks

• vulnerability within the community

• public transport confidence/ability/ability to be trained

• level of supervision required

• maximum benefit – do they participate/benefit with number of people around

• compatibility with others, e.g. issues participating with other genders precluding

group ratios

• opportunities/abilities to learn from others and form natural relationships

• unpredictable or ad hoc support needs such as behavioural support or toileting

support [s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant material].

Relevant considerations can include personal, environmental and institutional factors.

Personal factors can include:

• goals and lifestyle

• physical features of the person (height, weight etc.)

• functional capacity of the person (e.g. capacity to assist with transfers or to self-

mobilise)

• the behaviour and personality of the person (e.g. presence of behaviours of concern,

how well they get on with the staff)

• the person’s capacity to engage in social activities (need for prompting, active

inclusion etc.)

• need for assistive technology / availability of assistive technology

Page 225 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

Environmental factors can include:

• risk of the activity (e.g. swimming, operating tools/equipment)

• complexity of the activity (e.g. complex employment tasks, navigating crowded

event)

• duration of the activity (e.g. travel time, short trip to the shops, day trip out of town)

• risk in the environment (e.g. beach, busy urban streets, crowded events)

Institutional factors can include:

• consideration of the needs of all individuals in a group

• manual handling policy of the organisation

• availability of assistive technology, accessible vehicles etc.

• availability of trained staff

• other staffing needs (e.g. scheduled breaks, support for staff with a disability)

• legislative requirements, codes of practice, professional guidelines

This list is not exhaustive. The complexity and interdisciplinarity of determining support ratios

may provide a clue as to why there is very little research directly focussing on the topic.

5.1 Manual Handling

Safe Work Australia and state-based work safety organisations have codes of practice relating

to manual handling tasks [9,10,11]. The Safe Work Australia

Code of Practice for Hazardous

Manual Tasks suggests that, to maximise worker safety, transfer equipment should be

preferred to team handling. In other words, where possible a single person should assist a

patient or client using suitable assistive technology rather than two or more people assisting a

patient or client manual y. There are of course exceptions for equipment that is designed to be

operated by two people [9]. A 2011 Work Safe Victoria guideline suggests that two people may

be required to operate an electric hoist where the patient or client is not able to assist [10]. A

2006 manual handling guideline from the NSW Department of Ageing, Disability and Home

Care (now the Department of Community and Justice) states that clients with uncontrolled

movement may require two carers for personal care tasks. The guideline also recommends the

development of a Client Manual Handling plan for risk management and support planning [12].

Phil ips, Mellson and Richards emphasise the importance of individual risk assessments rather

than just assuming that one or two carers are appropriate for transfers [13]. Thornton observes

that two carers are often required for floor hoists, while a single carer is required for ceiling

hoists. The latter is safer and generally more cost effective [14]. Determining whether 1:1 or

2:1 is required for transfers depends on the suitability of available equipment with implications

for funding of ceiling hoists or floor hoists.

Page 226 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

5.2 Behaviours of concern

Behaviours of concern are a frequent reason for requesting higher staff ratios. I could not find

any research directly investigating the relationship between staff ratios and behaviours of

concern. A 2021 Cochrane review completed by researchers at the NDIS Quality and

Safeguard Commission investigated organisational interventions for reducing use of restrictive

practices. They listed 11 potential interventions but did not explicitly consider staffing numbers

or staff-client ratios as a factor in use of restrictive practices [15]. Correspondence with the

author of this review suggested other potential sources (refer to s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant material

). A 2009 report from the Victorian government

summarises the relationship between staffing levels and restrictive practices:

Staffing factors have been identified as critical, though there is a lack of consensus in

the literature as to how best to determine optimum staffing numbers. Higher staffing

ratios have been suggested as a means of enabling early intervention and prevention of

escalation. However, the availability of higher levels of staff have also been associated

with a greater likelihood of staff using physical interventions, if for no other reason than

they have the person power available to do so. Similarly, while lower staffing ratios

make it practically more difficult to use restraint, lower staffing levels can also contribute

to staff feeling anxious and consequently more likely to deploy restrictive practices

earlier than they might otherwise do so had they the support (reassurance and security)

of other staff close by who could offer assistance if required. Further research into these

issues is necessary [16].

Relating specifically to staff-client ratios, the report refers to a study in which the researchers

found higher staff to patient ratios resulted in increased use of restrictive practice when the

staff in question were nursing assistants. However, there was a decreased use of restrictive

practices when the staff in question were registered nurses [16]. This finding could not be

corroborated as the reference appears to be incorrect, however it does coincide with other

research that suggests training has a greater effect than staff numbers. Singh et al found that

training staff with mindfulness techniques reduced staff interventions for aggression and this

was true at low, moderate and high staff-client ratios [17].

6. Social service analogues

I looked into the literature related to ratios of support in aged care and childcare. Unfortunately,

the literature did not add much to the considerations already raised above.

There is inconsistent evidence that ratios of support affect children’s learning and

developments in early learning environments. A 2016 study by Iluz, Adi-Japha and Klein found

some association between ratios of support and positive peer interactions [18]. A later

systematic review found “child-staff ratios for pre-school aged children classrooms have small,

if any, associations with concurrent or subsequent child outcomes” [19]. Though ultimately the

standard of evidence in the reviewed papers was low.

Page 227 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

In the context of aged care, a study by Baker et al found that abuse is more likely to occur in

situations where there is not sufficient staff to complete all the work [20]. A study by Karimi-

Shahanjarini et al found that insufficient staff in a hospital setting leads to lack of organisation

and ‘ad hoc’ shifting of tasks [21]. In both these cases, it is not clear what counts as

‘insufficient staff’. While the findings might be relevant to determining the importance of proper

ratios, they do not support planning for what those ratios might be.

7. Appendix – Correspondence

I sent an initial inquiry to 13 professional occupational therapy organisations via email on 30th

September 2021 (refer to table below). With minor variations for individual organisations, the

message read:

I am completing some research for the National Disability Insurance Agency, the

organisation that administers Australia’s National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS).

The NDIS provides support to eligible people with intellectual, physical, sensory,

cognitive and psychosocial disability.

I am currently compiling existing research on how occupational therapists determine

ratios of support for community access and group social activities. I am interested in

how this is achieved internationally.

It is common practice for Occupational Therapists to recommend support ratios required

by their clients. For example, while one person may require 2:1 direct assistance for

certain tasks, another person might thrive with 1:7 supervision for the same task. My

questions are:

• What considerations go into determining the appropriate ratio of individual support

(i.e. 1:1 or 2:1)?

• What considerations go into determining a safe and effective ratio of group support

(i.e. 1:3 versus 1:7)?

I’m hoping you might be able to provide some information on how your members

determine the appropriate ratio of support. If possible can you please provide any:

• recommendations you make to your members regarding ratios of support

• best practice guidelines you may have developed or refer to in order to determine

appropriate ratios of support

• existing research you appeal to in making recommendations / developing guidelines

for ratios of support

• contacts you believe may be able to assist with my inquiry.

Thank you very much for your time and all the best

Page 228 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant material

Page 231 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant material

Page 232 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant material

Page 233 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant material

Page 234 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant material

Page 235 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant material

Page 236 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant material

Page 237 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant material

8. References

[1] s22(1)(a)(ii)

J.

- irrelevant m

Resource to Assist with Determining Personal Care Hours. TAB Research Team

paper 2021.

[2] Verdugo MA, Aguayo V, Arias VB, García-Domínguez L. A systematic review of the

assessment of support needs in people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Int J

Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(24):9494.

[3] Giné C, Font J, Guàrdia-Olmos J, Balcells-Balcells A, Valls J, Carbó-Carreté M. Using the

SIS to better align the funding of residential services to assessed support needs. Res Dev

Disabil. 2014;35(5):1144–51.

[4] Arnold SRC, Riches VC, Stancliffe RJ. I-CAN: the classification and prediction of support

needs. J Appl Res Intel ect Disabil. 2014;27(2):97–111.

[5] International SIS Use [Internet]. American Association on Intellectual and Developmental

Disabilities. [cited 2021 Oct 6]. Available from: https://www.aaidd.org/sis/international.

[6] Profile Form. Supports Intensity Scale [Internet]. American Association on Intellectual and

Developmental Disabilities. [cited 2021 Oct 6]. Available from:

https://www.aaidd.org/docs/default-source/sis-docs/sis form do not copy.pdf?sfvrsn=2.

[7] I-CAN [Internet]. Centre for Disability Studies. [cited 2021 Oct 6]. Available from:

https://www.i-can.org.au/.

[8] Lukersmith S (ed.) ICARE (Insurance and Care NSW). Guidance on the support needs for

adults with spinal cord injury. 2017. Sydney, Australia.

[9] Code of Practice for Hazardous Manual Tasks [Internet]. Safe Work Australia. [cited 2021

Oct 6]. Available from:

https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/system/files/documents/1905/model-cop-hazardous-

manual-tasks.pdf.

[10] A health and safety solution – assisting people who have fallen [Internet].

WorkSafeVictoria. [cited 2021 Oct 6]. Available from:

https://content.api.worksafe.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2018-06/ISBN-A-health-and-safety-

solution-assisting-people-who-have-fallen-2011-05.pdf.

[11] Code of Practice for Hazardous Manual Tasks [Internet]. Safe Work NSW. [cited 2021 Oct

6]. Available from:

https://www.safework.nsw.gov.au/ data/assets/pdf file/0020/50078/Hazardous-manual-

tasks-COP.pdf.

Page 238 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

[12] Best Practice Guidelines for Manual Handling [Internet]. Department of Ageing, Disability

and Home Care. [cited 2021 Oct 6]. Available from:

http://disabilitysafe.org.au/sites/default/files/DADHC Best Practice Guidelines MH.pdf.

[13] Phil ips J, Mellson J and Richardson N. It takes two? exploring the manual handling myth.

2014. University of Salford. Available from: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/43619/.

[14] Thornton S. An ergonomics approach to managing transfers from two handed to single

handed care [Thesis]. Loughborough University. [cited 2021 Oct 6]. Available from:

https://iosh.com/media/4403/sarah-thornton.pdf.

[15] Iffland M, Xu J, Gil ies D. Organisational interventions for decreasing the use of restrictive

practices with children or adults who have an intellectual or developmental disability. Cochrane

Libr [Internet]. 2021; Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd013840.

[16] McVilly K. Physical restraint in disability services: Current practices, contemporary

concerns, and future directions [Report]. State Government of Victoria 2009.

[17] Singh NN, Lancioni GE, Winton ASW, Curtis WJ, Wahler RG, Sabaawi M, et al. Mindful

staff increase learning and reduce aggression in adults with developmental disabilities. Res

Dev Disabil [Internet]. 2006;27(5):545–58. Available from:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2005.07.002.

[18] Iluz R, Adi-Japha E, Klein PS. Identifying child–staff ratios that promote peer skil s in

childcare. Early Educ Dev [Internet]. 2016;27(7):1077–98. Available from:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2016.1175240.

[19] Perlman M, Fletcher B, Falenchuk O, Brunsek A, McMullen E, Shah PS. Child-staff ratios

in early childhood education and care settings and child outcomes: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. PLoS One [Internet]. 2017;12(1):e0170256. Available from:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170256.

[20] Baker PRA, Francis DP, Hairi NN, Othman S, Choo WY. Interventions for preventing

abuse in the elderly. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]; 2016(8):CD010321. Available

from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010321.pub2.

[21] Karimi-Shahanjarini A, Shakibazadeh E, Rashidian A, Hajimiri K, Glenton C, Noyes J, et

al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of doctor-nurse substitution strategies in

primary care: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet].

2019;4:CD010412. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010412.pub2.

Page 239 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

DOCUMENT 25

Home automation as an everyday living cost

The content of this document is OFFICIAL.

Please note:

The research and literature reviews collated by our TAB Research Team are not to be

shared external to the Branch. These are for internal TAB use only and are intended to

assist our advisors with their reasonable and necessary decision-making.

Delegates have access to a wide variety of comprehensive guidance material. If

Delegates require further information on access or planning matters, they are to call the

TAPS line for advice.

The Research Team are unable to ensure that the information listed below provides an

accurate & up-to-date snapshot of these matters

Research question: How common is home automation/”smart homes” in Australia?

What is the typical ‘scope of works’ for a standard ‘smart home’ vs disability-specific home

automation features?

What is the typical cost or price range to setup a ‘smart home’?

Are existing homes able to accommodate home automation without needing to upgrade

electrical features (e.g. switchboard, wiring)?

Is there a significant dif erence in outcomes between low cost solutions (e.g. Google Home)

and high cost solutions (e.g. Control 4)?

What is the current evidence base regarding home automation and people with disability? Is

there evidence home automation is linked to increased independence, or other positive

outcomes (e.g. improved quality of life, wellbeing)? Are there any best practice guidelines?

What is the Agency’s risk appetite for home automation requests? Do mitigation strategies

need to be put in place (e.g. TAB mandatory referral for requests above $20,000)?

Date: 09/05/2022

Requestor: Claire s22(1)(a)(ii)

- irrele

Endorsed by (EL1 or above): Sandi s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant material

Researcher: Aaron s22(1)(a)(ii)

- irrelevant ma

Cleared by: Stephanie s22(1)(a)(ii)

- irrelevant mate

Page 278 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

1. Contents

Home automation as an everyday living cost ............................................................................. 1

1.

Contents ....................................................................................................................... 2

2.

Summary ...................................................................................................................... 2

3.

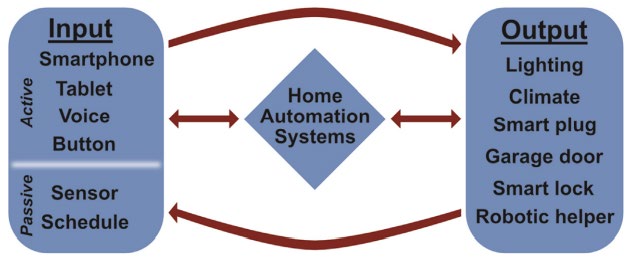

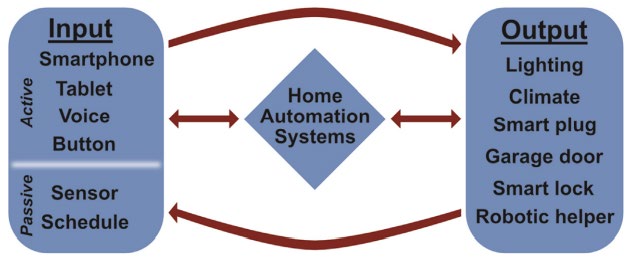

What is home automation? ........................................................................................... 3

4.

Home automation in Australia ....................................................................................... 4

5.

Home automation as a disability support ...................................................................... 4

5.1 Benefits ...................................................................................................................... 5

6.

Risk ............................................................................................................................... 7

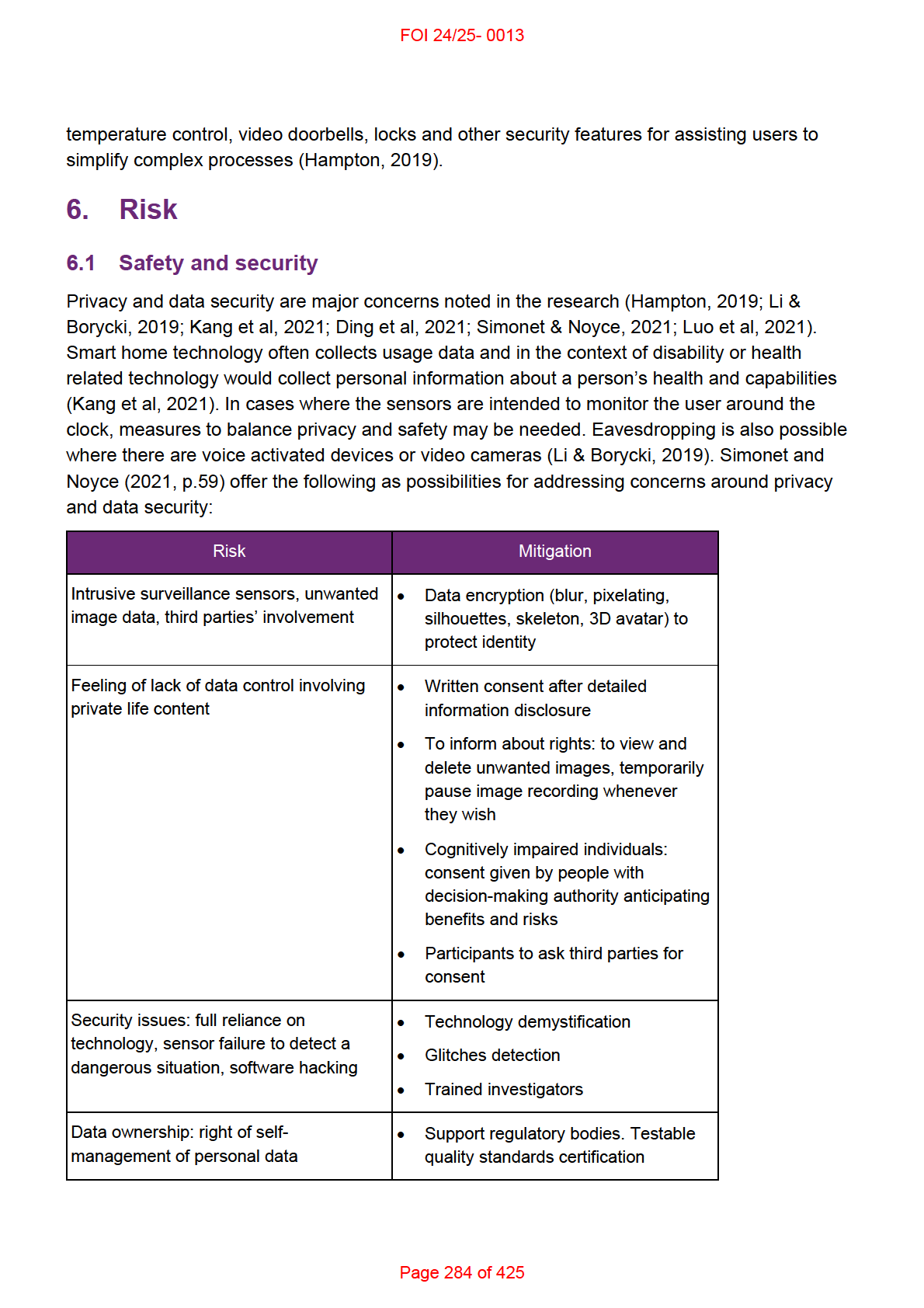

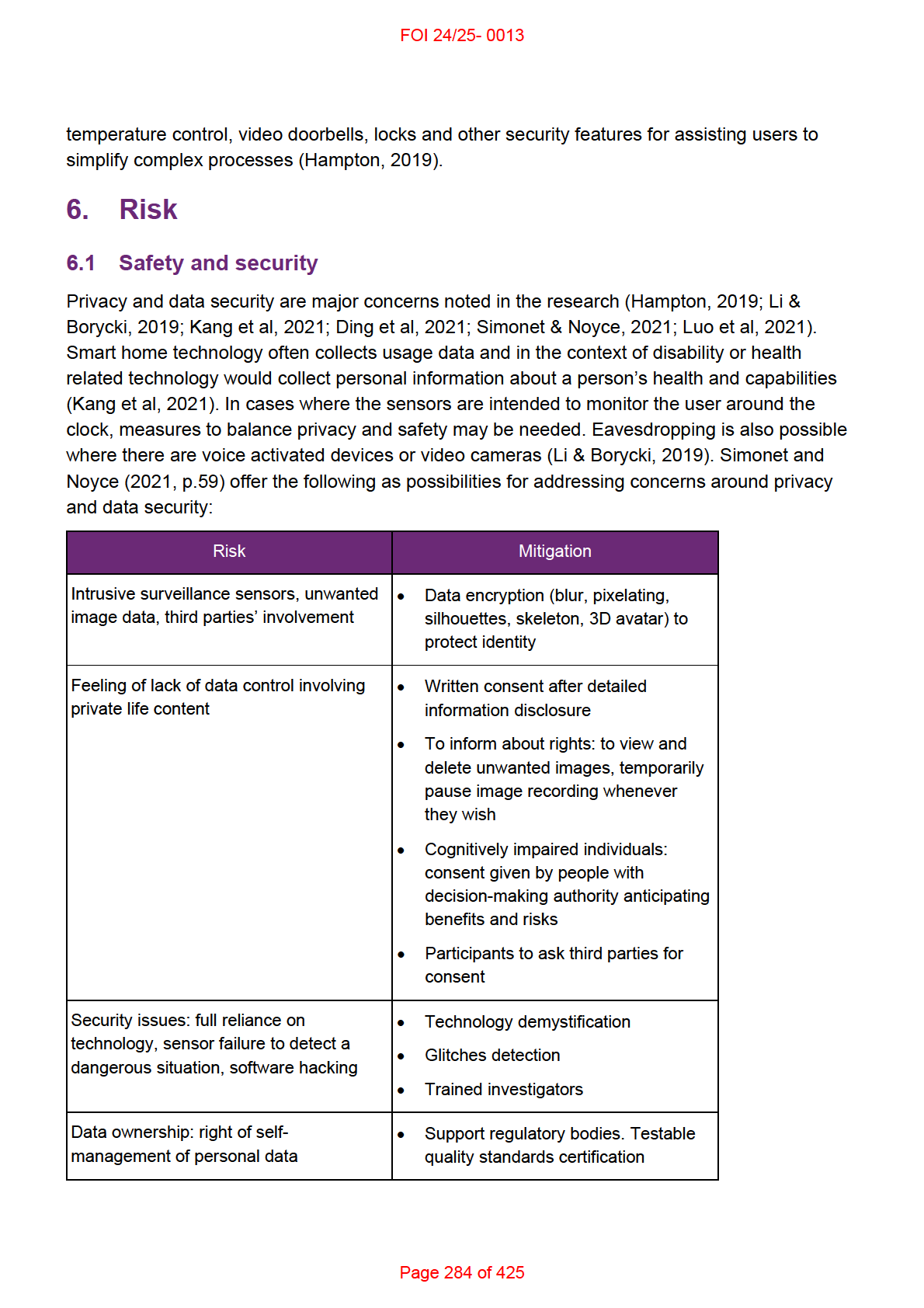

6.1 Safety and security .................................................................................................... 7

6.2 Cost effectiveness ..................................................................................................... 8

7.

References ................................................................................................................. 10

8.

Version control ............................................................................................................ 12

2. Summary

Smart home technology is growing in popularity in Australia. Most people having at least one

smart home device in their home. While common, only certain types of automations (eg.

entertainment) are ubiquitous in Australian homes. Whether a particular home automation

support is more likely an everyday living cost wil depend on the type and function of the

technology.

With the technology growing and changing, there is inconsistent and outdated information

online. Much of the research is still in very early stages and so the evidence base is minimal.

There is more research focussing on maintaining independence of older people compared to

other disability cohorts.

There is a body of research focussed on using sensors and the Internet of Things (IoT) in the

home to monitor and assess people at risk of various harms (for example, trips or falls, burns

when cooking etc.). Although home automations are often integrated with IoT, this paper will