FOI 24/25- 0013

DOCUMENT 32

Summary of evidence quality of 6 cooking skills

related articles

The content of this document is OFFICIAL.

Please note:

The research and literature reviews collated by our TAB Research Team are not to be shared

external to the Branch. These are for internal TAB use only and are intended to assist our

advisors with their reasonable and necessary decision-making.

Delegates have access to a wide variety of comprehensive guidance material. If Delegates

require further information on access or planning matters, they are to call the TAPS line for

advice.

The Research Team are unable to ensure that the information listed below provides an

accurate & up-to-date snapshot of these matters

Research question: Please evaluate the study quality of the following references provided

to TAB as support for a Thermomix for an individual with autism:

Nicollet, C., Zale, R., & Urbanowicz, A. (2016). Spectrum cooking. Evaluation of cooking classes

for young adults on the autism spectrum – executive summary.

Gustin, L., Funk, H. E., Reibolt, W., Parker, Em., Smith, N., & Blaine, R. (2020). Gaining

independence: cooking classes tailored for college students with autism (practice brief).

Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 33(4), 395-403.

Bal, V. H., Kim, S-H., Cheong, D., Lord, C. (2015). Daily living skills in individuals with autism

spectrum disorder from 2 to 21 years of age. Autism, 19(7), 774-784.

Goldschmidt, J., & Song, H-J. (2017). Development of cooking skills as nutrition intervention

for adults with autism and other developmental disabilities. Journal of the Academy of

Nutrition and Dietetics, 117(5), 671-679.

Smith, K. A., Ayres, K. A., Alexander, J., Ledford, J. R., Shepley, C., & Shepley, S. B. (2016).

Initiation and generalisation of self-instructional skills in adolescents with autism and

intellectual disability. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46, 1196-1209.

Ayres, K., & Cihak, D. (2010). Computer- and Video-based instruction of food-preparation

skills: acquisition, generalisation, and maintenance. Intellectual and Developmental

Disabilities, 48(3), 195-208.

Date: 23/2/2023

Requestor: Shannon s22(1)(a)(ii)

- irr

Endorsed by:

Page 345 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

Researcher: Stephanie s22(1)(a)(ii)

- irrelevant mate and Aaron s22(1)(a)(ii)

- irrelevant ma

Cleared by: Stephanie s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant mat

1. Contents

Summary of evidence quality of 6 cooking skil s related articles ................................................ 1

1.

Contents ....................................................................................................................... 2

2.

Summary ...................................................................................................................... 2

3.

Articles .......................................................................................................................... 2

2. Summary

Six articles are examined below. Five of the articles describe an intervention aiming to improve

cooking skil s of people with developmental disabilities. The other article is an observational

study examining predictors of daily living skills in people with autism. Five of the included

studies describe people with autism and three describe people with intellectual or other

developmental disabilities.

These studies provide low quality evidence that people with autism or intellectual disability can

be assisted to develop cooking skil s. The main limitations of the studies are high risk of bias,

low sample sizes, uncontrolled study designs and unsystematised review methods. No

randomised controlled trials or systematic reviews were included, which are considered the

highest quality of evidence due to a lower risk of bias.

None of the included studies discuss the Thermomix or any other thermal cookers available on

the market. In fact, while acknowledging the limitations of the articles included, they all support

the possibility of assisting people with autism or intellectual disability to learn traditional

cooking skil s.

3. Articles

Nicollet, C., Zale, R., & Urbanowicz, A. (2016). Spectrum cooking. Evaluation of cooking

classes for young adults on the autism spectrum – executive summary.

This study does not mention the Thermomix or any other thermal cookers available on the

market.

This reference is an executive summary of the research, even so the evidence quality is low:

only 4 individuals provided data about the cooking program and data was collected 12 months

after the program ceased which may introduce biased/distorted recol ections. There was no

control group as it related to feedback/lived-experience of a specific cooking class program.

Page 346 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

The research evaluated cooking classes for individuals with autism. The purpose of the

program was to practice cooking related skil s. Participants were assisted to practice skills

such as following recipes and kneading dough. The classes also provided an opportunity for

participants to try new foods, socialise and cooperate. There were four study participants

between the ages 18-22 years old (however the cooking classes involved 6 individuals).

Evaluation of the cooking classes was qualitative via structured interview with key questions.

This data was collected 12 months after the cooking class program finished. The research did

not discuss appliances used in the cooking program and whether study participants found

cooking appliances beneficial.

One of the feedback comments regarding the cooking program related to sensory

considerations, “…be mindful of the person’s needs, when it comes to Asperger’s they may not

like loud noises around you know, banging pots and everything, the smells might be too much

or something like that.”

Note: The following passage is taken from the Thermomix website acknowledging the volume:

How loud is the Thermomix ®? – Vorwerk International Help Center (2018)

The Thermomix ® works very quietly in almost all situations. As with all motorized

kitchen appliances, the Thermomix® may get noisier for a short time when starting to

chop hard foods such as grains, ice, or frozen fruits. The device produces a similar level

of noise to a grain mil , but it reduces after just a few seconds.

If the Thermomix is to loud. As using the Thermomix® to chop big pieces of vegetables, the device may start to

vibrate and produce a loud noise. If that happens, consider

cutting the vegetables

into smaller pieces that may fit between the cutting knife of the device.

Assure that

the device lays stable on an even surface and that

there is nothing under the

device like a power cord.

Considering the finishing sound of the device that informs you that the step is finished,

you may set up the volume of that sound in the device settings.

Gustin, L., Funk, H. E., Reibolt, W., Parker, Em., Smith, N., & Blaine, R. (2020). Gaining

independence: cooking classes tailored for col ege students with autism (practice

brief). Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 33(4), 395-403.

This study does not mention the Thermomix or any other thermal cookers available on the

market.

Evidence quality is low: it is a pre-test post-test design without a control group, the participant

number is small, the outcome measures were based on a questionnaire completed by the

participants which is vulnerable to bias.

The article reviews the effectiveness of a six week cooking course designed to teach cooking

skil s to college students with autism. The cooking program was part of a broader ‘Learning

Independence for Empowerment (LIFE) Project’ for students with disabilities. The paper states

that recipes in the cooking class were intended to teach basic skil s without becoming

Page 347 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

overwhelming for the students, such as knife skil s, baking, cooking on a stove top and using a

blender.

The literature review conducted by the authors acknowledged the link between autism traits

and feeding behaviour that may impact health and daily living skil s. Out of 16 cooking class

participants, full data-sets (pre- and post-tests) were collected from 11; study participants were

aged between 19-26 years old. The outcomes for the research were to determine if the

cooking classes increased cooking confidence, increased frequency of cooking at home, and

increased wil ingness to try new foods. It was found the students increased their home cooking

by an average of one meal per week, confidence in cooking increased, and acceptance of new

foods increased. The research does not describe how much of each specific cooking skil was

practiced and if one cooking method was preferred by participants over another. The research

mentions appliances such as stove and blender bit does not describe whether or how often

participants used appliances.

Bal, V. H., Kim, S-H., Cheong, D., Lord, C. (2015). Daily living skills in individuals with

autism spectrum disorder from 2 to 21 years of age. Autism, 19(7), 774-784.

This study does not mention the Thermomix or any other thermal cookers available on the

market.

Evidence quality is low-to-moderate due to the study design and potential lack of

generalisability. This study is a longitudinal observational study with no control group. While

the study starts with a good sized sample, attrition over time reduced the representativeness of

the group and therefore limits generalisability.

The study purpose was to investigate predictors of attainment of daily living skil s for

individuals with autism. Daily living skills were measured by the Vinelands scale for adaptive

functioning and was recorded at regular intervals (2, 3, 5, 9, 10, 13, 18 and 21 years old). This

data was used to predict the trajectory of daily living skil s for individuals with autism. Food

preparation skil s were assessed as part of the Vineland interview, though this aspect of daily

living skills received only minimal focus as part of the study.

Goldschmidt, J., & Song, H-J. (2017). Development of cooking skil s as nutrition

intervention for adults with autism and other developmental disabilities. Journal of the

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 117(5), 671-679.

This study does not mention the Thermomix or any other thermal cookers available on the

market.

Evidence quality is low due to study design and risk of bias. This study is a narrative literature

review and opinion piece.

The authors argue that cooking skil s can change a person’s relationship with food as well as

contribute to improved nutritional status. The article is a promotion of a program called Active

Engagement, which is aims to increase generalised cooking skil s and independence in the

kitchen for adults with autism. In the first stage of the program, participants were required to

Page 348 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

prepare salads by learning learn how to chop, cut, grate and peel. Once participants

demonstrated these skil s, they could progress to the next stage of using small, low risk, low

appliances and eventually larger appliances. This article only focuses on the first salad-making

stage of the program and does not detail study participants’ experience with using cooking

appliances.

Smith, K. A., Ayres, K. A., Alexander, J., Ledford, J. R., Shepley, C., & Shepley, S. B.

(2016). Initiation and generalisation of self-instructional skil s in adolescents with

autism and intel ectual disability. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46,

1196-1209.

This study does not mention the Thermomix or any other thermal cookers available on the

market.

Evidence quality is low due to study design. This is a pre-test/post-test study with no control

group and a small sample size of just 4 participants.

The study investigated whether video material can facilitate self-instructional learning for

adolescents with autism and intellectual disability. The content of the videos included kitchen,

office and other household skil s. Kitchen processes included putting popcorn in the

microwave, brushing zucchini with olive oil, and making lemonade.

Note: Although this research did not reference Thermomix or thermal cookers,

some

Thermomix (TM6) guided-cooking recipes now have video instructions which it could be

argued is a similar scenario to this research of teaching an individual to self-instruct.

Ayres, K., & Cihak, D. (2010). Computer- and Video-based instruction of food-

preparation skil s: acquisition, generalisation, and maintenance. Intel ectual and

Developmental Disabilities, 48(3), 195-208.

This study does not mention the Thermomix or any other thermal cookers available on the

market.

Evidence quality is low due to study design and age of paper. This is a pre-test/post-test study

with no control group and a small sample size of just 3 participants. The paper was published

13 years ago, which may affect the relevance of the technology-based interventions described.

This study evaluated the effect of computer-based video instruction on learning life skil s, such

as making a sandwich, microwaving soup or setting a table. Computer-based video instruction

was found to facilitate skil acquisition in the immediate term, however skil s were shown to

have declined at the 6- and 12-week assessments. On repeating the training, the skil was

reacquired.

Note: Although this research did not reference Thermomix or thermal cookers,

some

Thermomix (TM6) guided-cooking recipes now have video instructions which it could be

argued is a similar scenario to this research of teaching an individual to self-instruct.

Page 349 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

DOCUMENT 34

Transcranial magnetic stimulation for the

treatment of psychosocial conditions

The content of this document is OFFICIAL.

Please note:

The research and literature reviews collated by our TAB Research Team are not to be shared

external to the Branch. These are for internal TAB use only and are intended to assist our

advisors with their reasonable and necessary decision-making.

Delegates have access to a wide variety of comprehensive guidance material. If Delegates

require further information on access or planning matters, they are to call the TAPS line for

advice. The Research Team are unable to ensure that the information listed below provides an

accurate & up-to-date snapshot of these matters

Research question: What is the efficacy of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for adults

with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, Bipolar Disorder and/or Depression? Is there evidence

of impact on functional outcomes such as social and economic participation?

Date: 23/06/2023

Requestor: Jil ian s22(1)(a)(ii)

- irrelevant mater

Endorsed by: Katrin s22(1)(a)(ii)

- irreleva

Researcher: Aaron s22(1)(a)(ii)

- irrelevant ma

Cleared by: Stephanie s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant mat

1. Contents

Transcranial magnetic stimulation for the treatment of psychosocial conditions ........................ 1

1.

Contents ....................................................................................................................... 1

2.

Summary ...................................................................................................................... 2

3.

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation ................................................................................ 2

4.

Guidelines ..................................................................................................................... 3

5.

Major Depressive Disorder ........................................................................................... 4

6.

Bipolar disorder ............................................................................................................. 5

7.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder ................................................................................... 5

8.

References ................................................................................................................... 6

Page 370 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

2. Summary

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) is a type of non-invasive brain stimulation. There is a

substantial body of literature relating to use of repetitive TMS (rTMS) to treat many psychiatric

and neurological disorders. This paper focusses on Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), bipolar

disorder and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD).

Most clinical practice guidelines and systematic reviews agree that rTMS is an effective

treatment for symptoms of depression, especially treatment resistant Major Depressive

Disoder (MDD). There is stil some debate regarding treatment protocols and ef ect sizes.

While there is evidence that rTMS can be effective for bipolar disorder and OCD, it is more

tentative than in the case of MDD. The treatment may be offered in these cases where other

treatments have not been successful. There is wide agreement in the research that

heterogeneity of treatment protocols and small sample sizes in primary studies make it difficult

to draw more definite conclusions.

Evidence of improvements in functional outcomes for MDD, bipolar and OCD is minimal. Some

evidence exists around cognitive function. There is some evidence that rTMS can improve

cognitive function in healthy people as well as people with psychosocial conditions. However,

more evidence is required to establish this. No experimental evidence relating to efficacy of

rTMS to improve social or economic participation was found.

3. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

TMS is a type of non-invasive brain stimulation, which is a variety of neuromodulation or

neurostimulation. rTMS is generally safe and well-tolerated by patients and patients are

conscious during treatment. TMS involves the application of a wire coil to the patient’s head

which sends a pulsed magnetic field through the skull into the brain to alter brain function

(RANZCP, 2018a; RANZCP, 2018b; Hyde et al, 2022; Moses et al, 2023).

Single-pulse or paired-pulse TMS involves delivering one or two pulses to the patient’s brain

and is used primarily for exploratory or diagnostic purposes. Repetitive TMS is used for

therapeutic purposes and involves delivering recurring pulses to a specific brain region to

induce changes in brain activity. (Mann & Malhi, 2023; Klomjai et al, 2015).

Most research has focussed on rTMS for the treatment of depression but there is a substantial

literature base describing its use for other psychiatric disorders, neurological and

neurodevelopmental disorders, movement disorders, epilepsy, chronic pain and tinnitus (Tikka

et al, 2023; Mann & Malhi, 2023; Moses et al, 2023; Hyde et al, 2022; Lefaucher et al, 2020).

Protocols for rTMS can vary by:

• length or number of sessions frequency during a treatment block

• frequency, intensity, duration, or pattern of stimulus

• brain region targeted

Page 371 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

• coil-type or other device parameters

• additional or simultaneous treatments (Gutierrez et al, 2022; Klomjai et al, 2015).

Recognised varieties of rTMS include:

• theta-burst stimulation (TBS) –uses multiple bursts of high frequency stimulation

over a shorter session (Voigt et al, 2021)

• accelerated TMS (aTMS) – treatment sessions are scheduled multiple times per day

over a shorter overall treatment period (Somnez et al, 2019)

• deep TMS (dTMS) –uses a specialised coil to deliver pulses to deeper brain regions

(Gutierrez et al, 2022)

• priming TMS (pTMS) – a sub-threshold stimulus is delivered with the intention of

making the brain region more receptive to subsequent treatment (Lee et al, 2021).

4. Guidelines

Professional Practice Guidelines from the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of

Psychiatrists (RANZCP) supports the use of rTMS for depression, especially treatment

resistant depression and as a treatment of auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia (RANZCP,

2018a; RANZCP, 2018b).

Further evidence has emerged since the publication of the RANZCP guidelines. 2020 clinical

guidelines from a European team of clinicians notes definite efficacy of rTMS for depression

and probable efficacy for its use in treating PTSD, auditory hallucinations and negative

symptoms of schizophrenia. These guidelines note only possible efficacy for treatment of OCD

(Lefaucher et al, 2020).

A clinical practice guideline jointly published by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and

U.S. Department of Defense recommends TMS for treatment resistant MDD, but notes only

weak evidence in its favour (McQuaid et al, 2022).

Recent clinical guidelines from the Indian Psychiatric Society offer a strong recommendation

for the use of high frequency rTMS to treat acute episodes of depression. They offer moderate

or low strength recommendations for the use of rTMS to treat bipolar disorder, generalised

anxiety disorder, OCD, post-traumatic stress disorder, negative symptoms of schizophrenia,

nicotine use disorder, Alzheimer’s disease, insomnia, migraine, fibromyalgia and tinnitus

(Tikka et al, 2023).

Page 372 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

5. Major Depressive Disorder

Clinical practice guidelines and systematic reviews generally support TMS as a safe and

effective treatment for MDD. Evidence is strongest for the efficacy of high frequency rTMS on

acute depressive episodes (Tikka et al, 2023; Hyde et al, 2022; Lefaucher et al, 2020) and

treatment resistant depression (McQuaid et al, 2022; RANZCP, 2018b).

Brini et al (2022) reviewed 29 systematic reviews including 15 meta-analyses of TMS efficacy

for patients with MDD. They found authors of all studies agreed that TMS is effective for

reducing depressive symptoms of MDD. However, the authors conclude that TMS may be less

efficacious and less well tolerated than current literature suggests. After reviewing meta-

analyses, Brini et al found that the effect sizes were generally smaller than reported. They also

report that systematic reviews included in the study are mostly of very low quality and show

high risk of bias. Primary studies included in the reviews also show a high level of

heterogeneity in treatment protocols.

There is evidence of improved cognitive function after TMS in people with MDD, including

executive function, set-shifting ability, visual scanning, and psychomotor speed (Xu et al 2023;

Torres et al, 2023; Tateishi et al, 2022; Struckman et al, 2021; Schaffer et al, 2020; Martin et

al, 2017). Begeman et al (2020) found only small improvements in working memory and

attention. Tikka et al (2023) note that if a patient’s depressive symptoms respond to TMS, it is

more likely they wil see improvements in executive function as well.

Very few studies report on other functional outcomes of TMS treatments. A Canadian health

technology assessment offers some qualitative evidence that rTMS treatment improves

patient’s quality of life:

When it came to the nature of the improvement, participants often described the lifting of

a weight off their shoulders and the disappearance of negative thoughts. Often activities

of daily living were easier to do and could be done with greater energy. Some

participants mentioned a change in sleep pattern or greater appetite (Ontario Health,

2021, p.119)

The same report conducted a systematic review of 68 studies and found only one that reported

functional outcomes (Taylor et al, 2018). Another government funded Canadian review

identified Taylor et al (2018) as the only study reporting functional outcomes (Pohar & Farah,

2019). This RCT assessed efficacy of rTMS on 32 people with MMD. The Work and Social

Adjustment Scale (WSAS) and the Global Assessment of Function (GAF) were used as

secondary outcome measures. The study found no significant effect on either WSAS or GAF

scores after rTMS treatment (Taylor et al, 2018).

One large observational study of 257 people with treatment resistant MDD found a significant

improvement in function following rTMS treatment using the Clinical Global Impressions survey

(CGI-S). The effect was maintained at 3, 6, 9 and 12 month follow ups (Denner et al, 2014).

Page 373 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

6. Bipolar disorder

Mutz (2023) and Tikka et al (2023) note evidence that TMS is effective in treating bipolar

disorder using high frequency stimulation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. However,

numerous other studies find no significant effect compared to sham controls. Researchers

conclude that further research is needed to determine if TMS is effective in treating bipolar

(Mutz, 2023; Hyde et al, 2022; Elsayed et al, 2022; Hett & Marhawa, 2020; Gold et al, 2019).

Mutz et al (2023) report evidence from 2 studies indicating improvement in cognitive function

after TMS. An RCT assessing 52 people with bipolar disorder found improve across all

cognitive measures compared to sham control. A pilot study assessing 16 people with bipolar

disorder found improvements in verbal learning but no other cognitive functions. However,

more studies reviewed found no significant effect (Mutz et al, 2023; Hett & Marhawa, 2020).

No other information on functional outcomes was found.

7. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Recent systematic reviews note general positive results from studies investigating effects of

TMS on symptoms of OCD, especially low frequency stimulation of the dorsolateral prefrontal

cortex or supplementary motor area. However, reviewers also uniformly cite small sample

sizes, inconsistent results and heterogeneity of treatment protocols as factors reducing

confidence in any positive recommendations (Tikka et al, 2023; Hyde et al, 2022; Fitzimmons

et al, 2022; Pellegrini et al, 2022; Yu et al, 2022; Liang et al, 2021; Lefaucher et al, 2020;

Rapinesi et al, 2019). Liang et al (2021) observe that despite evidence of efficacy, research

into the effect of TMS on OCD stil requires adequately sized and controlled studies.

Rapinesi et al suggest rTMS may be a suitable treatment for patients who do not respond to

pharmacological treatment. This is echoed in the 2017 OCD clinical practice guidelines from

the Indian Psychiatric Society, which suggests TMS only after multiple unsuccessful

medication trials (Janardhan Reddy et al, 2017). In contrast, Pellegrini et al (2022) find that

rTMS is most effective in patients not resistant to medication or who have had only one

unsuccessful medication trial. They therefore recommend TMS earlier rather than later in the

treatment pathway.

Fitzimmons et al (2022) and Yu et al (2022) note large and significant improvements in CGI-S

after rTMS, indicating likelihood of some functional improvement in patients. No other

information on functional outcomes was found.

Page 374 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

8. References

Begemann, M. J., Brand, B. A., Ćurčić-Blake, B., Aleman, A., & Sommer, I. E. (2020). Efficacy

of non-invasive brain stimulation on cognitive functioning in brain disorders: a meta-

analysis.

Psychological medicine,

50(15), 2465–2486.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720003670

Dunner, D. L., Aaronson, S. T., Sackeim, H. A., Janicak, P. G., Carpenter, L. L., Boyadjis, T.,

Brock, D. G., Bonneh-Barkay, D., Cook, I. A., Lanocha, K., Solvason, H. B., &

Demitrack, M. A. (2014). A multisite, naturalistic, observational study of transcranial

magnetic stimulation for patients with pharmacoresistant major depressive disorder:

durability of benefit over a 1-year follow-up period.

The Journal of clinical psychiatry,

75(12), 1394–1401. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13m08977

Elsayed, O. H., Ercis, M., Pahwa, M., & Singh, B. (2022). Treatment-Resistant Bipolar

Depression: Therapeutic Trends, Challenges and Future Directions.

Neuropsychiatric

disease and treatment, 18, 2927–2943. https:/ doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S273503

Fitzsimmons, S. M. D. D., van der Werf, Y. D., van Campen, A. D., Arns, M., Sack, A. T.,

Hoogendoorn, A. W., other members of the TETRO Consortium, & van den Heuvel, O.

A. (2022). Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for obsessive-compulsive

disorder: A systematic review and pairwise/network meta-analysis.

Journal of affective

disorders, 302, 302–312. https:/ doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.01.048

Hett, D., & Marwaha, S. (2020). Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in the Treatment

of Bipolar Disorder.

Therapeutic advances in psychopharmacology, 10,

2045125320973790. https://doi.org/10.1177/2045125320973790

Hyde, J., Carr, H., Kel ey, N., Seneviratne, R., Reed, C., Parlatini, V., Garner, M., Solmi, M.,

Rosson, S., Cortese, S., & Brandt, V. (2022). Efficacy of neurostimulation across mental

disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis of 208 randomized controlled trials.

Molecular psychiatry,

27(6), 2709–2719. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01524-8

Gold, A. K., Ornelas, A. C., Ciril o, P., Caldieraro, M. A., Nardi, A. E., Nierenberg, A. A., &

Kinrys, G. (2019). Clinical applications of transcranial magnetic stimulation in bipolar

disorder.

Brain and behavior,

9(10), e01419. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1419

Gutierrez, M. I., Poblete-Naredo, I., Mercado-Gutierrez, J. A., Toledo-Peral, C. L., Quinzaños-

Fresnedo, J., Yanez-Suarez, O., & Gutierrez-Martinez, J. (2022). Devices and

Technology in Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation: A Systematic Review.

Brain sciences,

12(9), 1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12091218

Janardhan Reddy, Y. C., Sundar, A. S., Narayanaswamy, J. C., & Math, S. B. (2017). Clinical

practice guidelines for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder.

Indian journal of psychiatry,

59(Suppl 1), S74–S90. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.196976

Page 375 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

Klomjai, W., Katz, R., & Lackmy-Vallée, A. (2015). Basic principles of transcranial magnetic

stimulation (TMS) and repetitive TMS (rTMS).

Annals of physical and rehabilitation

medicine,

58(4), 208–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2015.05.005

Lee, J. C., Corlier, J., Wilson, A. C., Tadayonnejad, R., Marder, K. G., Ngo, D., Krantz, D. E.,

Wilke, S. A., Levit , J. G., Ginder, N. D., & Leuchter, A. F. (2021). Subthreshold

stimulation intensity is associated with greater clinical efficacy of intermittent theta-burst

stimulation priming for Major Depressive Disorder.

Brain stimulation,

14(4), 1015–1021.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2021.06.008

Lefaucheur, J. P., Aleman, A., Baeken, C., Benninger, D. H., Brunelin, J., Di Lazzaro, V.,

Filipović, S. R., Grefkes, C., Hasan, A., Hummel, F. C., Jääskeläinen, S. K., Langguth,

B., Leocani, L., Londero, A., Nardone, R., Nguyen, J. P., Nyffeler, T., Oliveira-Maia, A.

J., Oliviero, A., Padberg, F., … Ziemann, U. (2020). Evidence-based guidelines on the

therapeutic use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS): An update (2014-

2018).

Clinical neurophysiology: official journal of the International Federation of Clinical

Neurophysiology,

131(2), 474–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2019.11.002

Liang, K., Li, H., Bu, X., Li, X., Cao, L., Liu, J., Gao, Y., Li, B., Qiu, C., Bao, W., Zhang, S., Hu,

X., Xing, H., Gong, Q., & Huang, X. (2021). Ef icacy and tolerability of repetitive

transcranial magnetic stimulation for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder in

adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis.

Translational psychiatry,

11(1),

332. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01453-0

Mann, S. K., & Malhi, N. K. (2023). Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. In

StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

Martin, DM, McClintock, SM, Forster, J, Lo, TY, Loo, CK. (2017). Cognitive enhancing effects

of rTMS administered to the prefrontal cortex in patients with depression: A systematic

review and meta-analysis of individual task effects.

Depression and Anxiety. 34: 1029–

1039. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22658

McQuaid, J. R., Buelt, A., Capaldi, V., Ful er, M., Issa, F., Lang, A. E., Hoge, C., Oslin, D. W.,

Sall, J., Wiechers, I. R., & Wil iams, S. (2022). The Management of Major Depressive

Disorder: Synopsis of the 2022 U.S. Department of Veterans Af airs and U.S.

Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline.

Annals of internal medicine,

175(10), 1440–1451. https://doi.org/10.7326/M22-1603

Moses, T. E. H., Gray, E., Mischel, N., & Greenwald, M. K. (2023). Effects of neuromodulation

on cognitive and emotional responses to psychosocial stressors in healthy humans.

Neurobiology of stress, 22, 100515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2023.100515

Mutz J. (2023). Brain stimulation treatment for bipolar disorder.

Bipolar disorders,

25(1), 9–24.

https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.13283

Ontario Health (Quality) (2021). Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for People With

Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Health Technology Assessment.

Ontario health

Page 376 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

technology assessment series,

21(4), 1–232.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/34055112/

Pel egrini, L., Garg, K., Enara, A., Gottlieb, D. S., Wel sted, D., Albert, U., Laws, K. R., &

Fineberg, N. A. (2022). Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (r-TMS) and

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-resistance in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A

meta-analysis and clinical implications.

Comprehensive psychiatry,

118, 152339.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2022.152339

Pohar, R., & Farrah, K. (2019). Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Patients with

Depression: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness, Cost-Effectiveness and Guidelines – An

Update. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545105/

Janardhan Reddy, Y. C., Sundar, A. S., Narayanaswamy, J. C., & Math, S. B. (2017). Clinical

practice guidelines for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder.

Indian journal of psychiatry,

59(Suppl 1), S74–S90. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.196976

Rapinesi, C., Kotzalidis, G. D., Ferracuti, S., Sani, G., Girardi, P., & Del Casale, A. (2019).

Brain Stimulation in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD): A Systematic Review.

Current neuropharmacology,

17(8), 787–807.

https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X17666190409142555

Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. (2018a). Position Statement –

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. https://www.ranzcp.org/clinical-guidelines-

publications/clinical-guidelines-publications-library/repetitive-transcranial-magnetic-

stimulation

Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. (2018b). Professional Practice

Guideline – Administration of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation.

https://tmsact.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/PPG16-Administration-of-repetitive-

transcranial-magnetic-stimulation-rTMS-2.pdf

Schaffer, D. R., Okhravi, H. R., & Neumann, S. A. (2021). Low-Frequency Transcranial

Magnetic Stimulation (LF-TMS) in Treating Depression in Patients With Impaired

Cognitive Functioning.

Archives of clinical neuropsychology : the official journal of the

National Academy of Neuropsychologists,

36(5), 801–814.

https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acaa095

Sonmez, A. I., Camsari, D. D., Nandakumar, A. L., Voort, J. L. V., Kung, S., Lewis, C. P., &

Croarkin, P. E. (2019). Accelerated TMS for Depression: A systematic review and meta-

analysis.

Psychiatry research,

273, 770–781.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.041

Struckmann, W., Persson, J., Gingnell, M., Weigl, W., Wass, C., & Bodén, R. (2021).

Unchanged Cognitive Performance and Concurrent Prefrontal Blood Oxygenation After

Page 377 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

Accelerated Intermittent Theta-Burst Stimulation in Depression: A Sham-Controlled

Study.

Frontiers in psychiatry, 12, 659571. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.659571

Tateishi, H., Mizoguchi, Y., & Monji, A. (2022). Is the Therapeutic Mechanism of Repetitive

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Cognitive Dysfunctions of Depression Related to

the Neuroinflammatory Processes in Depression?.

Frontiers in psychiatry, 13, 834425.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.834425

Tikka, S. K., Siddiqui, M. A., Garg, S., Pattojoshi, A., & Gautam, M. (2023). Clinical Practice

Guidelines for the Therapeutic Use of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in

Neuropsychiatric Disorders.

Indian journal of psychiatry,

65(2), 270–288.

https://doi.org/10.4103/indianjpsychiatry.indianjpsychiatry 492 22

Torres, I. J., Ge, R., McGirr, A., Vila-Rodriguez, F., Ahn, S., Basivireddy, J., Walji, N., Frangou,

S., Lam, R. W., & Yatham, L. N. (2023). Effects of intermittent theta-burst transcranial

magnetic stimulation on cognition and hippocampal volumes in bipolar depression.

Dialogues in clinical neuroscience,

25(1), 24–32.

https://doi.org/10.1080/19585969.2023.2186189

Voigt, J.D., Leuchter, A.F. & Carpenter, L.L. (2021). Theta burst stimulation for the acute

treatment of major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Translational Psychiatry,

11, 330. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01441-4

Xu, M., Nikolin, S., Samaratunga, N. et al. Cognitive Effects Following Of line High-Frequency

Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (HF-rTMS) in Healthy Populations: A

Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. (2023) Neuropsychology Review.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-023-09580-9

Yu, L., Li, Y., Yan, J., Wen, F., Wang, F., Liu, J., Cui, Y., & Li, Y. (2022). Transcranial Magnetic

Stimulation for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Tic Disorder: A Quick Review.

Journal of integrative neuroscience,

21(6), 172. https:/ doi.org/10.31083/j.jin2106172

Page 378 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

DOCUMENT 35

Evaluation of CANS, ABAS-3 and LSP-16 outcome

measures

The content of this document is OFFICIAL.

Please note:

The research and literature reviews collated by our TAB Research Team are not to be shared

external to the Branch. These are for internal TAB use only and are intended to assist our

advisors with their reasonable and necessary decision-making.

Delegates have access to a wide variety of comprehensive guidance material. If Delegates

require further information on access or planning matters, they are to call the TAPS line for

advice.

The Research Team are unable to ensure that the information listed below provides an

accurate & up-to-date snapshot of these matters

Research question: For each functional outcome measure (CANS; ABAS-3; LSP-16):

• What is the intended population?

• What populations is the measure reliable and valid for?

• How can the measure be used to maximise utility in prediction of care needs?

• What are the limitations?

• What are the risks and benefits of using the measure:

- as a stand alone tool?

- as part of a more comprehensive assessment?

- by a therapist who is unfamiliar with the client?

Date: 23/1/24

Requestor: Sarah s22(1)(a)(ii)

- irrelev

Endorsed by: Shannon s22(1)(a)(ii)

- irrelev

Researcher: Aaron s22(1)(a)(ii)

- irrelevant ma

Cleared by: Aaron s22(1)(a)(ii)

- irrelevant ma

Page 379 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

1. Contents

Evaluation of CANS, ABAS-3 and LSP-16 outcome measures ................................................. 1

1.

Contents ....................................................................................................................... 2

2.

Summary ...................................................................................................................... 2

3.

Care and Needs Scale .................................................................................................. 3

4.

Adaptive Behavior Assessment System, 3rd Edition ..................................................... 3

5.

Abbreviated Life Skil s Profile (LSP-16) ........................................................................ 4

6.

Summary of outcome measure features ....................................................................... 6

7.

References ................................................................................................................... 9

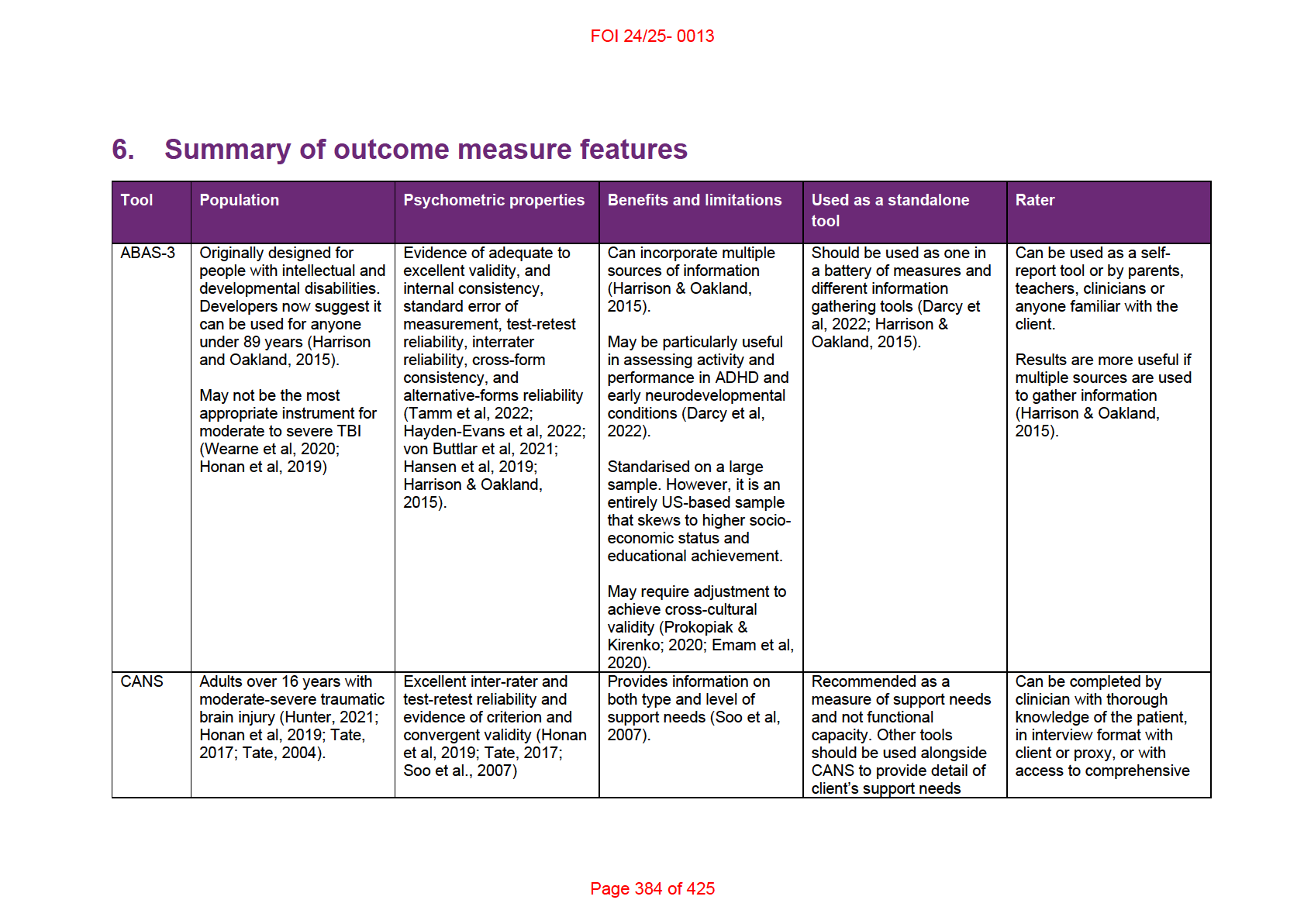

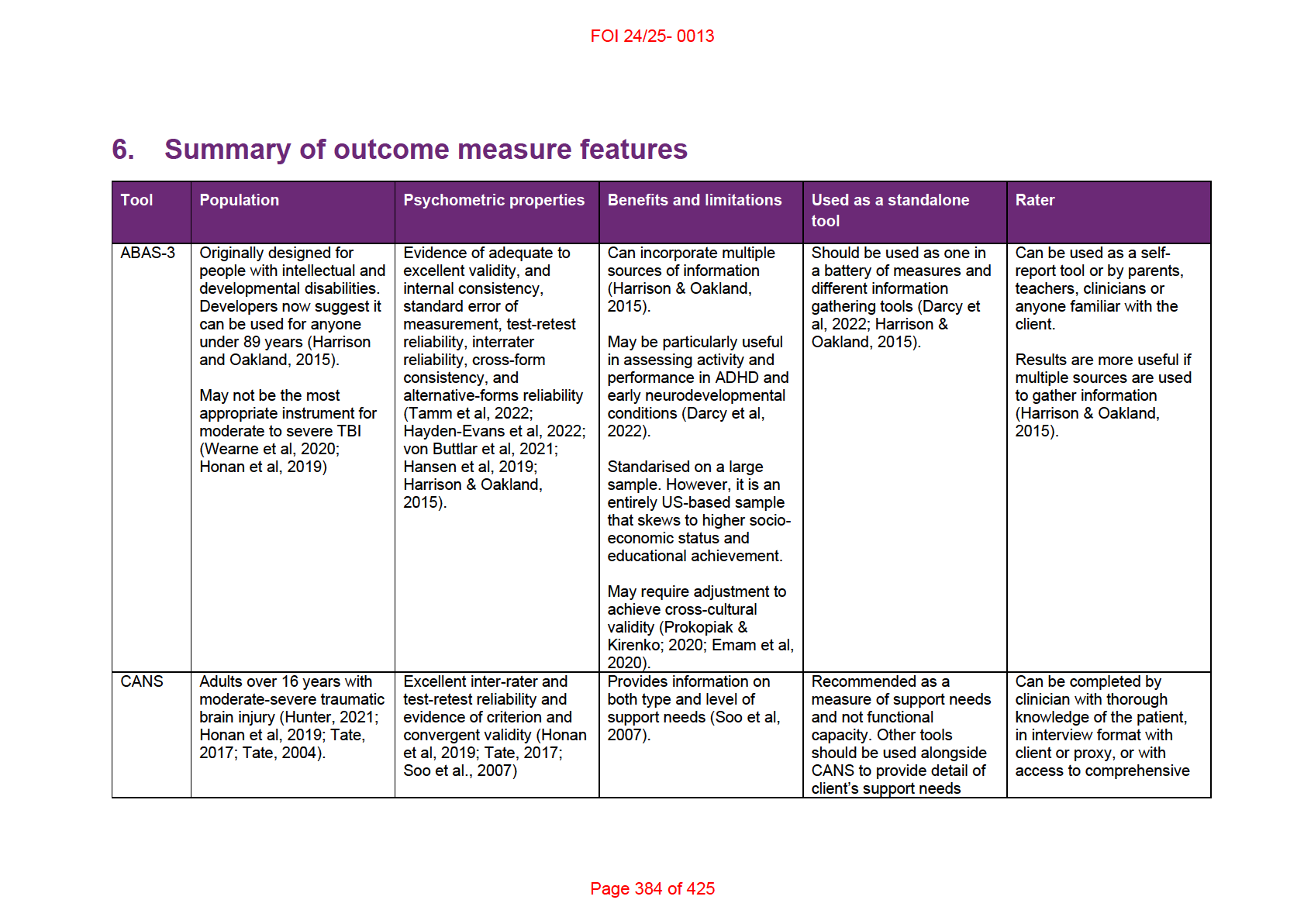

2. Summary

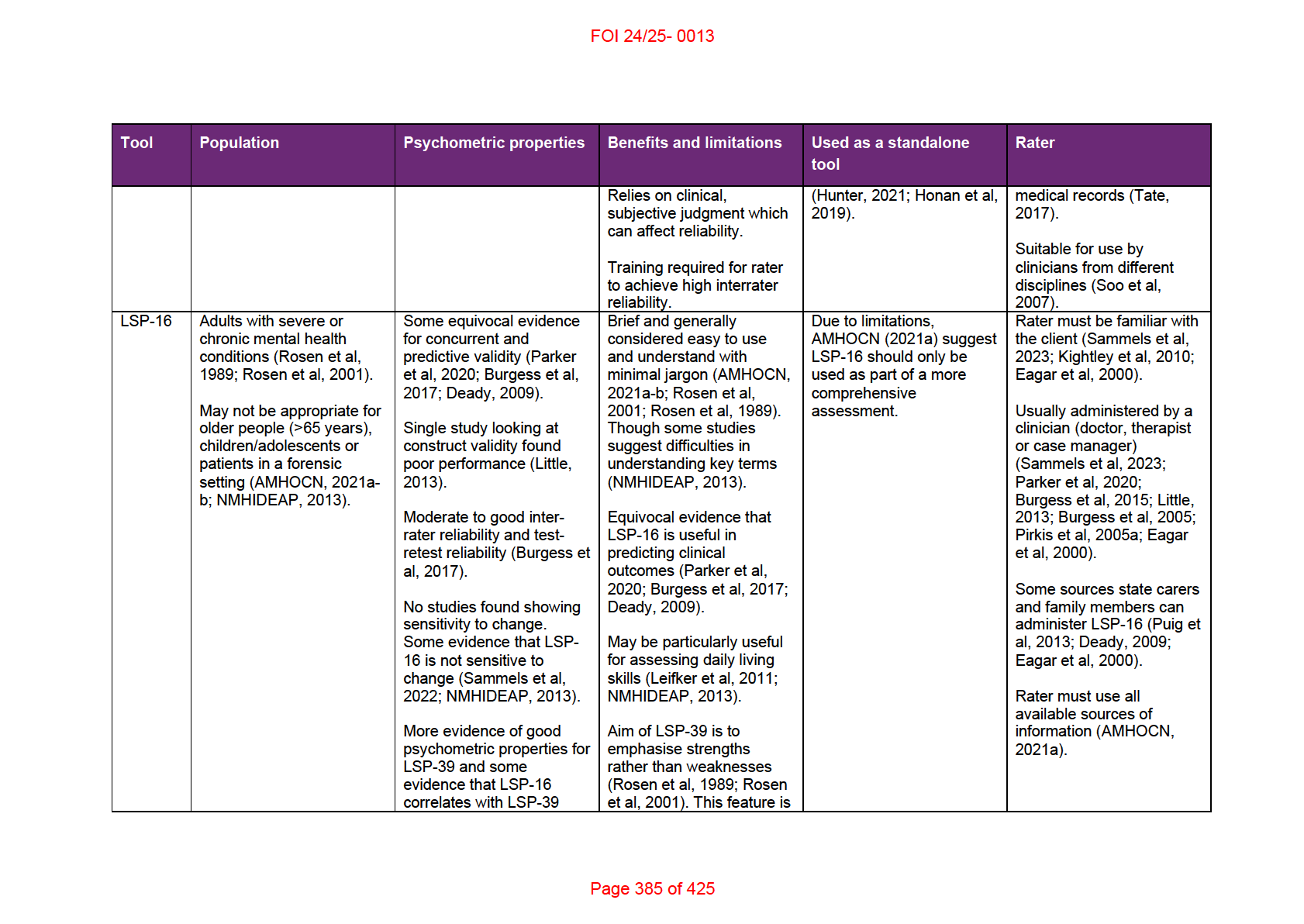

This paper examines the scope, psychometric properties and other features of three

commonly used outcome measures: Care and Needs Scale (CANS), Adaptive Behavior

Assessment System, 3rd Edition (ABAS-3) and Abbreviated Life Skil s Profile (LSP-16).

The outcome measures vary from narrow to general in scope. CANS is intended to assess

support needs for people over 16 years with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. LSP-16

is designed for adults with severe or chronic mental health conditions. ABAS-3 is more general

and developers suggest it can be used to assess adaptive behaviours for anyone under 89

years.

None of the three outcome measures are intended to be a standalone tool. It is intended that

all three are used in combination with other measures, assessments and information gathering

methods to generate a fuller picture of a person’s functional capacity or support needs.

The source of the information used to completed the assessments varies. ABAS-3 can be

completed by parents, teachers, co-workers, friends or clinicians familiar with the client and it

is recommended that information is collected from multiple sources. LSP-16 is usually

completed by a clinician but preference should be given to the treating professional or support

person with the greatest understanding of the client’s situation. CANS is completed by a

clinician but familiarity may be gained through an informal interview with the client or their

carer/proxy, or by sufficiently detailed medical records.

Results are further summarised in 6. Summary of outcome measure features.

Page 380 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

3. Care and Needs Scale

CANS was developed to assess support needs for people over 16 years with moderate to

severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) (Honan et al, 2019; Tate, 2017; Soo et al, 2007). A version

for younger people (PCANS) was also developed (Tate et al, 2014; Soo et al, 2010). CANS

can be completed in an interview format with the client or proxy or by a clinician with sufficient

knowledge of the client (Tate, 2017). The manual also notes:

the CANS can be completed on the basis of information derived from the patient’s

medical record, scales of disability and so forth. In situations where the clinician has

knowledge of the patient/client and direct interview is not required, the CANS wil only

take a few minutes to complete. Interview format with an informant generally takes

somewhat longer (10-15 mins)." (Tate, 2017, p.11)

Few studies have examined the psychometric properties of the CANS. The only studies found

were authored by the developers. Existing evidence indicates excellent inter-rater and test-

retest reliability as well as adequate convergent and criterion validity (Tate, 2017; Soo et al,

2007; Tate, 2004).

There are some sources of potential bias which may impact reliability. For example, Honan et

al (2019) note that the assessment depends on subjective judgement of the clinician and that

training is required in order to achieve high levels of inter-rater reliability. Further, the manual

states that it is not advised to separate out the support needs that may be due to conditions

other than TBI, such as support needs due to health conditions or aging (Tate, 2017).

However, this may impact reliability given that CANS has only been validated for TBI

populations and not general or other clinical cohorts.

4. Adaptive Behavior Assessment System, 3rd Edition

ABAS-3 was originally designed for people with intellectual and developmental conditions. It

has been standardised on a large scale and developers now suggest it can be used for

anyone under the age of 89 years, including:

persons who exhibit the effects of trauma, display attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

(ADHD), disruptive behaviors, anxiety disorders, mood disorders, neurocognitive

impairments, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), developmental delays and disorders,

eating disorders, health impairment, language disorders, learning disabilities and

disorders, neurobehavioral and neurodevelopmental disorders, motor impairment,

physical disabilities, personality disorders, psychotic and thought disorders, sensory

impairments, sleep disorders, substance-related disorders, or traumatic brain injury

(Harrison & Oakland, 2015, p.57).

Most evidence of psychometric properties of ABAS-3 comes from studies conducted by the

tool’s developers (Hayden-Evans et al, 2022). There is evidence of excellent internal

consistency, test-retest reliability and adequate to excellent inter-rater reliability and alternate-

Page 381 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

forms reliability. There is evidence of excellent content, construct and criterion validity

(Hayden-Evans et al, 2022; Harrison & Oakland, 2015.

Validity studies targeted at specific populations were conducted for autism, intellectual

disability, and ADHD. In addition, validity studies were conducted for the second edition

(ABAS-II) for people with:

developmental delay, low birth weight, perinatal respiratory distress, chromosomal

abnormalities, fetal alcohol syndrome and prenatal drug exposure, Down syndrome,

motor and physical disorders, expressive and receptive language disorders, behavioural

and emotional issues, learning disabilities, and hearing impairments; adults with

Alzheimer's and unspecified neuro-psychological disorders (Harrison & Oakland, 2015,

p.127).

The developers argue that ABAS-II is sufficiently similar to ABAS-3 for the previous version’s

evidence to stand in favour of the current version (Harrison & Oakland, 2015). However, there

are some notable differences. For example, ABAS-3 scores are generally higher than ABAS-II

scores (von Buttlar et al, 2021; Harrison & Oakland, 2015).

Some limitations were described in the literature. Despite evidence of good psychometric

properties, Hayden-Evans et al (2022) note that ABAS-3 does not have very good coverage

against the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) codes

deemed most relevant to children with autism. Further, while efforts were made to ensure

ABAS-3 was comprehensive, it should not be relied on as the sole instrument of assessment.

Clinicians should also look to other data such as “information derived from concurrent or

former assessments; detailed interviews and history taking; developmental, school, or work

records; and direct observations" (Harrison & Oakland, 2015, p.7).

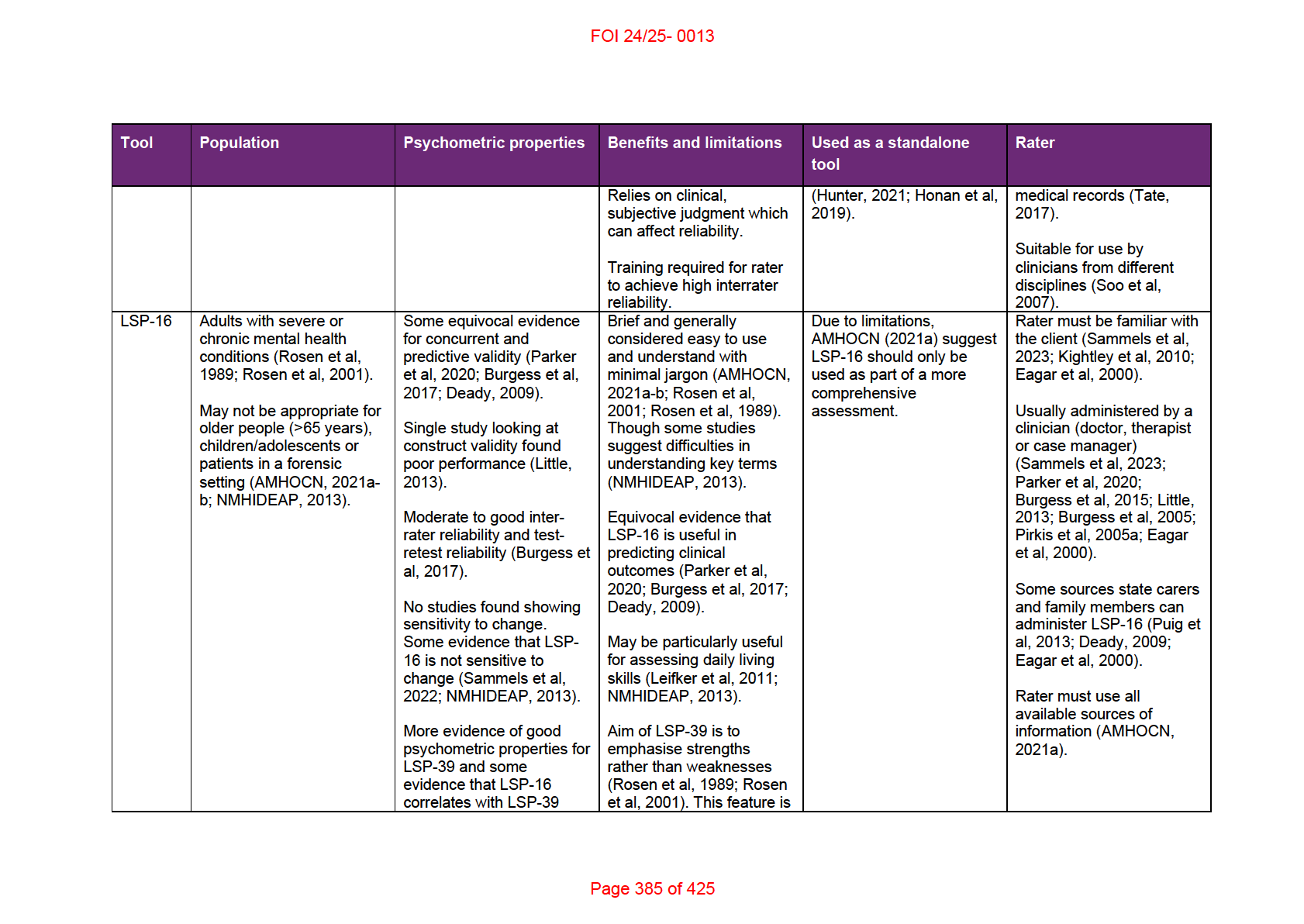

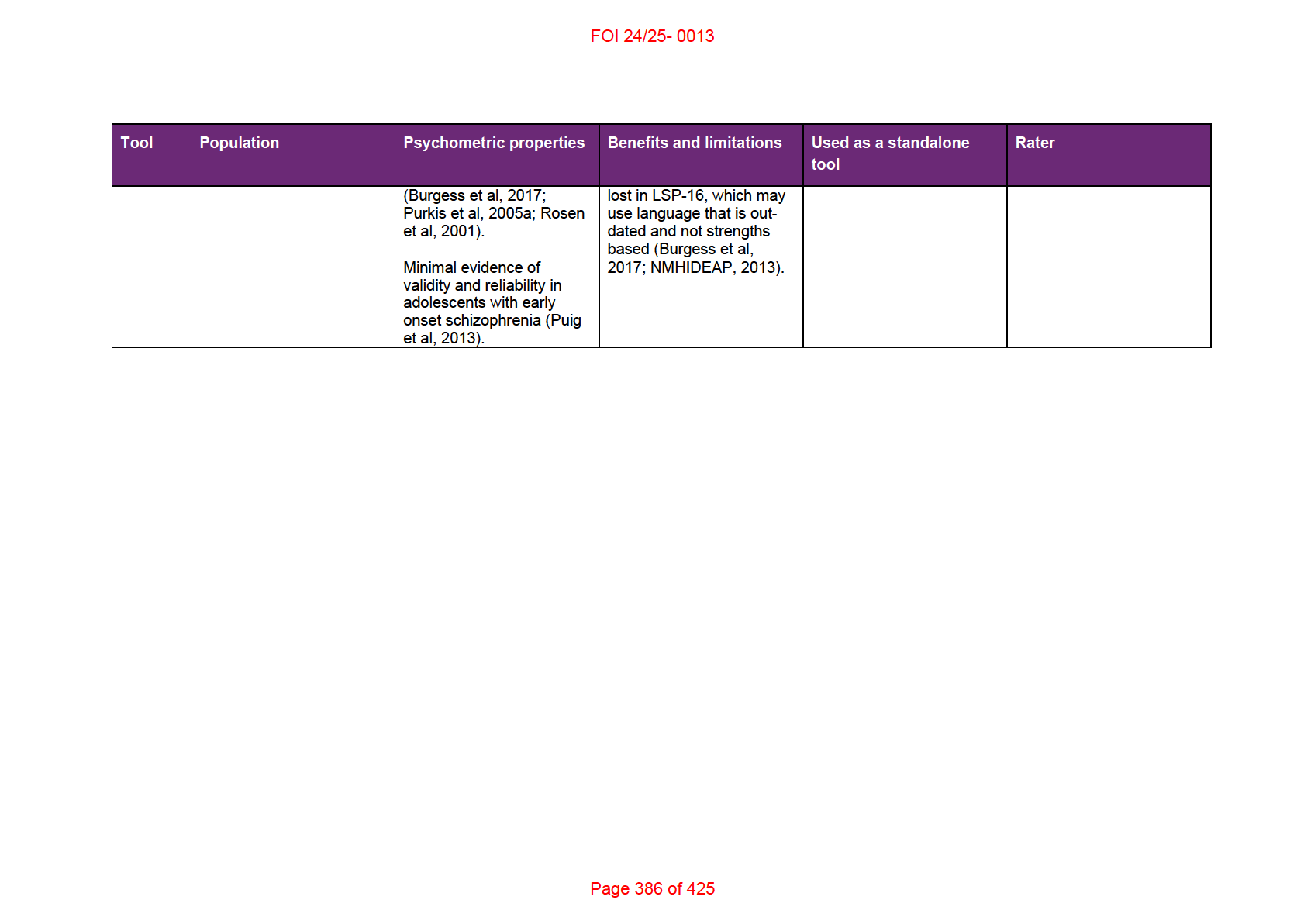

5. Abbreviated Life Skil s Profile

LSP-16 is a measure of community functioning and disability for people with severe or chronic

mental health conditions (Little, 2013; Kightley et al, 2010; Pirkis et al, 2005a; Rosen et al,

2001). It was developed for Australian public mental health services to reduce the rating

burden on clinicians (NMHIDEAP, 2013; Little, 2013; Pirkis et al, 2005a). As part of the

National Outcome Casemix Collection (NOCC), LSP-16 is now required to be used at certain

points in the treatment cycle for adults receiving specialised public sector mental health

services across Australia (AMHOCN, 2021a; Little, 2013; Rosen et al, 2001).

It is a shortened form of the 39 item Life Skills Profile (LSP-39). Rosen et al (1989) developed

the original LSP-39 to assess the daily functioning of people with schizophrenia and it has

since been applied generally for people with mental health or psychiatric conditions (Burgess

et al, 2017; Deady et al, 2005; Pirkis et al, 2005a). The developers note that only a few of the

items in the Communication subscale of LSP-39 related directly to features specific to

schizophrenia (Rosen et al, 1989). The Communication subscale was removed in the

development of LSP-16 (Deady et al, 2005; Rosen et al, 2001).

Page 382 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

Few studies have investigated the psychometric properties of LSP-16. There is equivocal

evidence of concurrent and predictive validity. It was shown to correlate with Health of the

Nation Outcome Scale and LSP-39 but not with the Behaviour and Symptom Identification

Scale (Burgess et al, 2017). There is some evidence that LSP-16 can predict clinical outcomes

such as hospital admission and length of stay, though other studies were not able to find

significant correlations (Parker et al, 2020; Burgess et al, 2017; Deady, 2009). There is

evidence of poor construct validity (Little, 2013). Studies have found moderate to good inter-

rater reliability and test-retest reliability (Burgess et al, 2017). Some studies suggest potential

problems for LSP-16’s sensitivity to change but no study has investigated this directly

(Sammels et al, 2022; NMHIDEAP, 2013).

More research has been conducted on the psychometric properties of LSP-39. The longer

version has been shown to be a valid and reliable measure for people with schizophrenia and

severe mental health issues. There is evidence that LSP-39 has moderately good content,

construct, concurrent and predictive validity, adequate inter-rater reliability, high test-retest

reliability and good sensitivity to change (Burgess et al, 2017; Deady, 2009; Pirkis et al,

2005a).

Some argue that evidence for LSP-39 can be used to support the validity and reliability of LSP-

16 as all 16 items of the abbreviated form are included in the longer version (Pirkis et al,

2005a; Rosen et al, 2001). And LSP-16 has been shown to correlate with LSP-39 (Burgess et

al, 2017; Rosen et al, 2001). However, there are some important differences between the two

forms. For example, LSP-39 is a strengths-based scale with higher scores indicating greater

functioning in a particular task, whereas LSP-16 is an impairment-based scale with higher

scores indicating greater impairment (Pirkis et al, 2005a; Rosen et al, 2001).

Several limitations of LSP-16 have been identified. A review of the NOOC in 2013

recommended removing the LSP-16 from the collection due to its reported limitations. Despite

the measure being mandatory, the 3-month period between reviews meant that it was not

administered to most service users, who are in community rehabilitation settings for less than

3 months. While its use in capturing some information around daily living skil s in adults was

seen as useful, it was found to be inappropriate for children and adolescents, older people and

those in a forensic setting. In addition:

Issues were noted in relation to particular items, including domains that are not

captured, the glossary and the language of the measure. Participants consistently raised

concerns regarding items 10, 11 and 16, which they thought required clarification in the

glossary. Some participants suggested that the tool does not capture fluctuations in

functioning between reviews, which they thought was of particular clinical relevance.

The language was felt to be outdated, not strengths based and not supporting the

recovery agenda.. Participants suggested that there were more useful types of

information to collect, including capturing aspects of social inclusion (NMHIDEAP, 2013,

p.130).

Page 383 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

7. References

Australian Mental Health Outcomes and Classification Network. (2021a).

National Outcomes

and Casemix Collection (NOCC) basic training manual: adult services 2nd Edition.

https://www.amhocn.org/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/731019/Adult-Basic-NOCC-

Training-Manual.pdf

Australian Mental Health Outcomes and Classification Network. (2021b).

National Outcomes

and Casemix Collection (NOCC) basic training manual: child and adolescent services.

https://www.amhocn.org/ data/assets/pdf file/0019/731026/Child-Adolescent-Basic-

NOCC-Training-Manual.pdf

Australian Mental Health Outcomes and Classification Network. (2021c).

Rater and clinical

utility training manual: Adult. Rev. ed. Sydney: Australian Mental Health Outcomes and

Classification Network.

https://www.amhocn.org/ data/assets/pdf file/0004/694030/Adult Rater Clinical Utilit

y Training Manual 100523.pdf

Australian Mental Health Outcomes and Classification Network. (2021d). Rater and clinical

utility training manual: Child and adolescent. Rev. ed. Sydney: Australian Mental Health

Outcomes and Classification Network.

https://www.amhocn.org/ data/assets/pdf file/0009/694467/CA Rater-and-Clinical-

Utility-Manual-100523.pdf

Burgess, P. M., Harris, M. G., Coombs, T., & Pirkis, J. E. (2017). A systematic review of

clinician-rated instruments to assess adults' levels of functioning in specialised public

sector mental health services.

The Australian and New Zealand journal of psychiatry,

51(4), 338–354. https:/ doi.org/10.1177/0004867416688098

Burgess, P., Pirkis, J., & Coombs, T. (2015). Routine outcome measurement in Australia.

International review of psychiatry,

27(4), 264–275.

https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2014.977234

Burgess, P., Coombs, T., Clarke, A., Dickson, R., & Pirkis, J. (2012). Achievements in mental

health outcome measurement in Australia: Reflections on progress made by the

Australian Mental Health Outcomes and Classification Network (AMHOCN).

International journal of mental health systems,

6(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-

4458-6-4

D'Arcy, E., Wal ace, K., Chamberlain, A., Evans, K., Milbourn, B., Bölte, S., Whitehouse, A. J.,

& Girdler, S. (2022). Content validation of common measures of functioning for young

children against the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health and

Code and Core Sets relevant to neurodevelopmental conditions.

Autism : the

international journal of research and practice,

26(4), 928–939.

https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613211036809

Page 387 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

Deady, M. (2009).

A review of screening, assessment and outcome measures for drug and

alcohol settings. Drug and Alcohol and Mental Health Information Management Project.

Sydney: NSW Department of Health.

https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/18266/1/NADA A Review of Screening%2C Assess

ment and Outcome Measures for Drug and Alcohol Settings.pdf

Eagar K, Buckingham B, Coombs T, Trauer T, Graham C, Eagar L & Callaly T. (2000).

Outcome Measurement in Adult Area Mental Health Services: Implementation

Resource Manual. Department of Human Services Victoria.

https://www.vgls.vic.gov.au/client/en_AU/search/asset/1160101/0

Emam, M. M., Al-Sulaimani, H., Omara, E., & Al-Nabhany, R. (2019). Assessment of adaptive

behaviour in children with intellectual disability in Oman: an examination of ABAS-3

factor structure and validation in the Arab context.

International journal of

developmental disabilities,

66(4), 317–326.

https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2019.1587939

Hansen, L. (2019). A Concurrent validity study of the Missouri Adaptive Ability Scale and the

Adaptive Behavior Assessment System, Third Edition — Teacher Form. Murray State

Theses and Dissertations. 149. https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/etd/149

Harrison, P. L., & Oakland, T. (2015). ABAS-3. Torrance: Western Psychological Services.

Hayden-Evans, M., Milbourn, B., D’Arcy, E., Chamberlain, A., Afsharnejad, B., Evans, K., ... &

Girdler, S. (2022). An evaluation of the overal utility of measures of functioning suitable

for school-aged children on the autism spectrum: A scoping review.

International

Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health,

19(21), 14114.

Honan, C. A., McDonald, S., Tate, R., Ownsworth, T., Togher, L., Fleming, J., Anderson, V.,

Morgan, A., Catroppa, C., Douglas, J., Francis, H., Wearne, T., Sigmundsdottir, L., &

Ponsford, J. (2019). Outcome instruments in moderate-to-severe adult traumatic brain

injury: recommendations for use in psychosocial research.

Neuropsychological

rehabilitation,

29(6), 896–916. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2017.1339616

Hunter, S. (2021).

Occupational Therapy Australia response to question taken on notice at

public hearing in Melbourne on 23 April 2021. Occupational Therapy Australia.

https://everyaustraliancounts.com.au/wp-content/uploads/QoN 03 IA.pdf

Kightley, M., Einfeld, S., & Hancock, N. (2010). Routine outcome measurement in mental

health: feasibility for examining effectiveness of an NGO.

Australasian psychiatry :

bulletin of Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists,

18(2), 167–169.

https://doi.org/10.3109/10398560903473660

Leifker, F. R., Patterson, T. L., Heaton, R. K., & Harvey, P. D. (2011). Validating measures of

real-world outcome: the results of the VALERO expert survey and RAND panel.

Schizophrenia bulletin,

37(2), 334–343. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbp044

Page 388 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

Little J. (2013). Multilevel confirmatory ordinal factor analysis of the Life Skil s Profile-16.

Psychological assessment,

25(3), 810–825. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032574

National Mental Health Information Development Expert Advisory Panel. (2013).

Mental Health

National Outcomes and Casemix Collection: NOCC Strategic Directions 2014 – 2024.

Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra. https:/ www.amhocn.org/training-and-service-

development/special-projects/nocc-strategic-directions-2014-2024

Parker, S., Arnautovska, U., Siskind, D., Dark, F., McKeon, G., Korman, N., & Harris, M.

(2020). Community-care unit model of residential mental health rehabilitation services in

Queensland, Australia: Predicting outcomes of consumers 1-year post discharge.

Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 29, E109.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796020000207

Pirkis, J., Burgess, P., Kirk, P., Dodson, S., & Coombs, T. (2005a).

Review of standardised

measures used in the National Outcomes and Casemix Collection (NOCC). New South

Wales Institute of Psychiatry. http:/ hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30073558

Pirkis, J., Burgess, P., Coombs, T., Clarke, A., Jones-Ellis, D., & Dickson, R. (2005b). Routine

measurement of outcomes in Australia's public sector mental health services.

Australia

and New Zealand health policy,

2(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-8462-2-8

Prokopiak, A. & Kirenko, J. (2020). ABAS-3 – an instrument for assessing adaptive skil s in

people with an intellectual disability.

Hrvatska revija za rehabilitacijska istraživanja,

56(2), 154-168. https://doi.org/10.31299/hrri.56.2.9

Puig, O., Penadés, R., Baeza, I., De la Serna, E., Sánchez-Gistau, V., Lázaro, L., Bernardo,

M., & Castro-Fornieles, J. (2013). Assessment of real-world daily-living skills in early-

onset schizophrenia trough the Life Skil s Profile scale.

Schizophrenia research,

145(1-

3), 95–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2012.12.026

Rosen, A., Hadzi-Pavlovic, D., & Parker, G. (1989). The life skil s profile: a measure assessing

function and disability in schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia bulletin,

15(2), 325–337.

https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/15.2.325

Rosen, A., Trauer, T., Hadzi-Pavlovic, D., & Parker, G. (2001). Development of a brief form of

the Life Skil s Profile: the LSP-20.

The Australian and New Zealand journal of

psychiatry,

35(5), 677–683. https://doi.org/10.1080/0004867010060518

Sammells, E., Logan, A., & Sheppard, L. (2023). Participant Outcomes and Facilitator

Experiences Following a Community Living Skil s Program for Adult Mental Health

Consumers.

Community mental health journal,

59(3), 428–438.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-022-01020-x

Soo, C., Tate, R. L., Anderson, V., & Waugh, M.-C. (2010). Assessing care and support needs

for children with acquired brain injury: Normative data for the Paediatric Care and

Needs Scale (PCANS).

Brain Impairment,

11(2), 183–196.

https://doi.org/10.1375/brim.11.2.183

Page 389 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

Soo, C., Tate, R., Hopman, K., Forman, M., Secheny, T., Aird, V., Browne, S., & Coulston, C.

(2007). Reliability of the care and needs scale for assessing support needs after

traumatic brain injury.

The Journal of head trauma rehabilitation,

22(5), 288–295.

https://doi.org/10.1097/01.HTR.0000290973.01872.4c

Tate, R.L. (2017).

Manual for the Care and Needs Scale (CANS). Unpublished manuscript.

John Walsh Centre for Rehabilitation Research, University of Sydney. Updated version

2. https:/ www.sydney.edu.au/content/dam/corporate/documents/faculty-of-medicine-

and-health/research/centres-institutes-groups/Care-and-needs-scale-manual.pdf

Tate, R. L. (2004). Assessing support needs for people with traumatic brain injury: the care

and needs scale (CANS),

Brain Injury,

18(5), 445-460,

https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050310001641183

Tamm, L., Day, H. A., & Duncan, A. (2022). Comparison of Adaptive Functioning Measures in

Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder Without Intellectual Disability.

Journal of

autism and developmental disorders,

52(3), 1247–1256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-

021-05013-9

von Buttlar, A. M., Zabel, T. A., Pritchard, A. E., & Cannon, A. D. (2021). Concordance of the

Adaptive Behavior Assessment System, second and third editions.

Journal of

intellectual disability research : JIDR,

65(3), 283–295. https:/ doi.org/10.1111/jir.12810

Wearne, T., Anderson, V., Catroppa, C., Morgan, A., Ponsford, J., Tate, R., Ownsworth, T.,

Togher, L., Fleming, J., Douglas, J., Docking, K., Sigmundsdottir, L., Francis, H.,

Honan, C., & McDonald, S. (2020). Psychosocial functioning following moderate-to-

severe pediatric traumatic brain injury: recommended outcome instruments for research

and remediation studies.

Neuropsychological rehabilitation,

30(5), 973–987.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2018.1531768

Page 390 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

DOCUMENT 36

Thermoregulation and air conditioning

The content of this document is OFFICIAL.

Please note:

The research and literature reviews collated by our TAB Research Team are not to be shared

external to the Branch. These are for internal TAB use only and are intended to assist our

advisors with their reasonable and necessary decision-making.

Delegates have access to a wide variety of comprehensive guidance material. If Delegates

require further information on access or planning matters, they are to call the TAPS line for

advice.

The Research Team are unable to ensure that the information listed below provides an

accurate & up-to-date snapshot of these matters

Research question: What medical conditions or disabilities involve an impairment in thermoregulation?

What cooling systems are available for use in Australia?

Is air conditioning effective in managing symptoms of thermoregulation impairment

compared to other cooling systems?

Date: 8/2/2024

Requestor: Helen s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant material

Endorsed by: Melinda s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant ma

Researcher: Aaron s22(1)(a)(ii)

- irrelevant ma

Cleared by: Stephanie s22(1)(a)(ii) - irrelevant mat

Page 391 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

1. Contents

Thermoregulation and air conditioning ....................................................................................... 1

1.

Contents ....................................................................................................................... 2

2.

Summary ...................................................................................................................... 3

3.

Human thermoregulation .............................................................................................. 4

3.1 Thermoeffectors ........................................................................................................ 4

4.

Conditions resulting in thermoregulation impairment .................................................... 5

4.1 Spinal cord injury ....................................................................................................... 7

4.2 Acquired brain injury .................................................................................................. 7

4.3 Parkinson’s Disease .................................................................................................. 8

4.4 Multiple Sclerosis ....................................................................................................... 8

4.5 Peripheral neuropathy ............................................................................................... 9

4.6 Psychosocial conditions ............................................................................................. 9

4.7 Epilepsy and seizure disorders ................................................................................ 10

4.8 Autism ...................................................................................................................... 10

4.9 Motor neurone disease / Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis............................................ 11

4.10 Huntington’s disease ............................................................................................ 11

4.11 Severe burns ........................................................................................................ 12

5.

Management of thermoregulation impairment ............................................................ 12

5.1 Air conditioning compared to other cooling strategies ............................................. 13

6.

Air conditioning and other cooling systems ................................................................. 14

6.1 Cooling garments .................................................................................................... 14

6.2 Fans ......................................................................................................................... 15

6.3 Evaporative cooling ................................................................................................. 15

6.4 Air conditioning (refrigerated cooling) ...................................................................... 15

7.

Air conditioning use in Australia .................................................................................. 17

8.

References ................................................................................................................. 19

Page 392 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

2. Summary

Note: This paper is a substantial revision of a research paper originally completed in October

2019 and reviewed in February 2024.

Thermoregulation impairment can result from a wide range of health conditions and

disabilities. The human thermoregulatory system involves perceptual, physiological and

behavioural components. A condition may result in a thermoregulatory impairment if it affects

the peripheral or central nervous systems, or if the condition impacts strength, mobility, motor

control, cognition or emotional regulation.

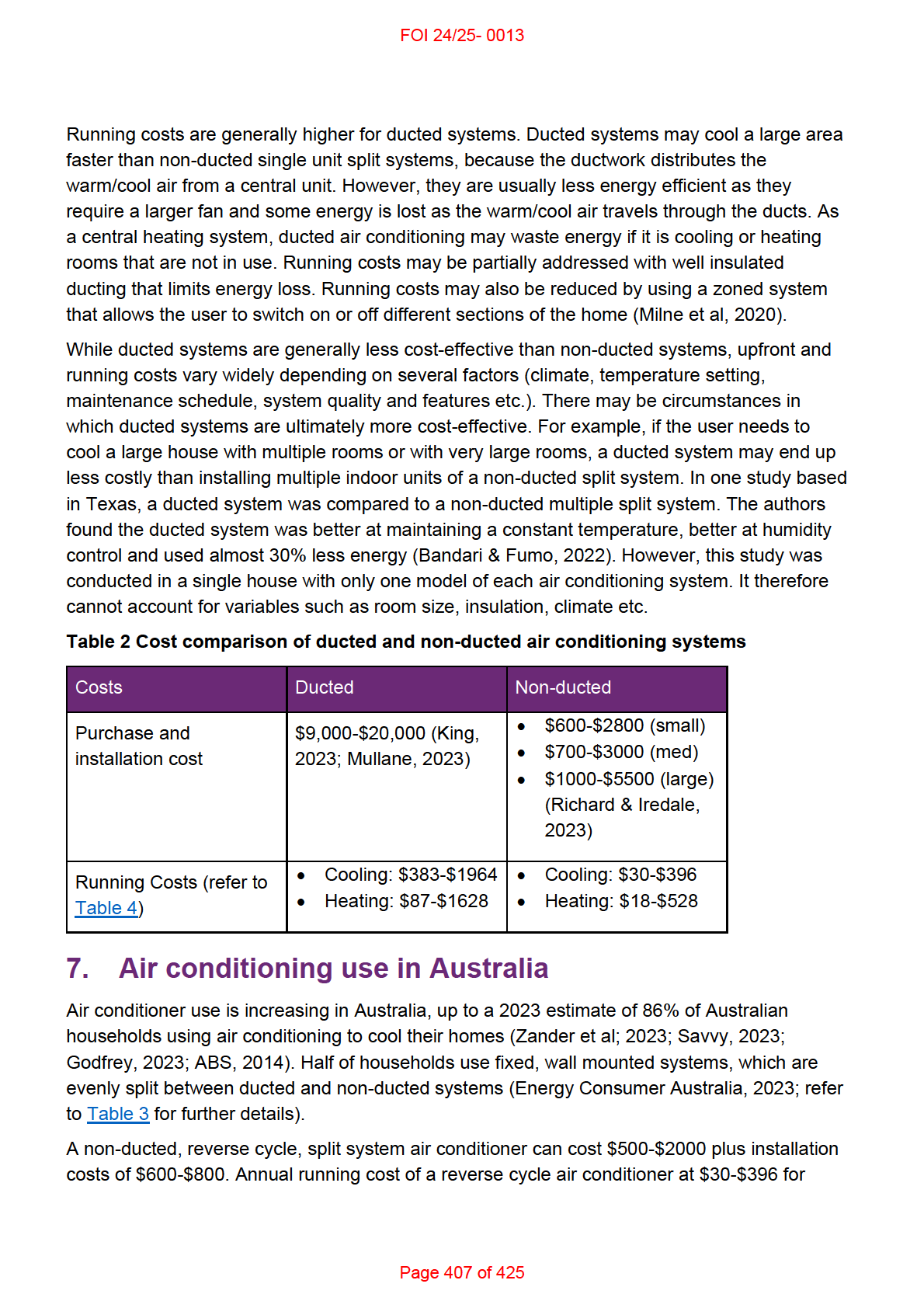

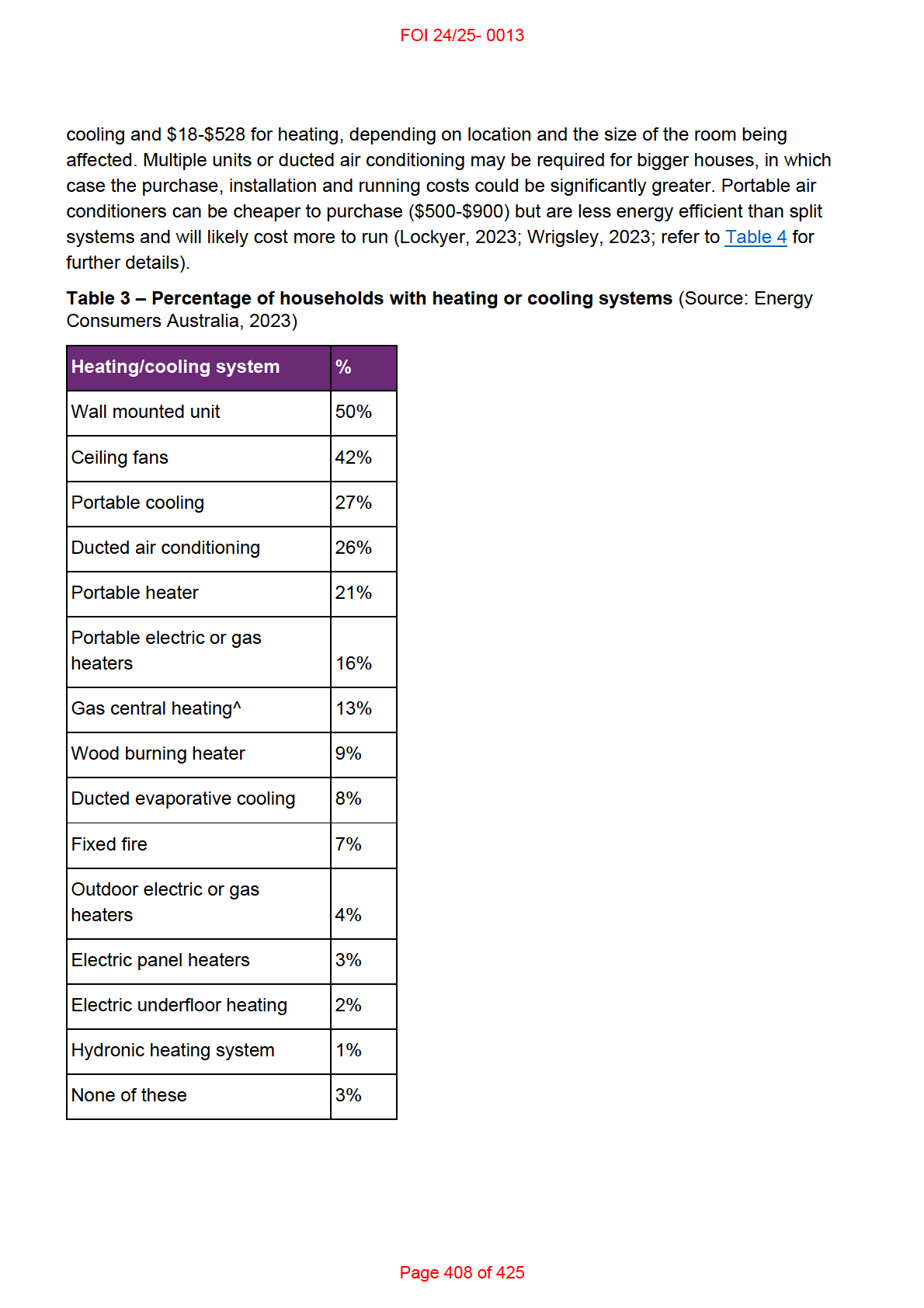

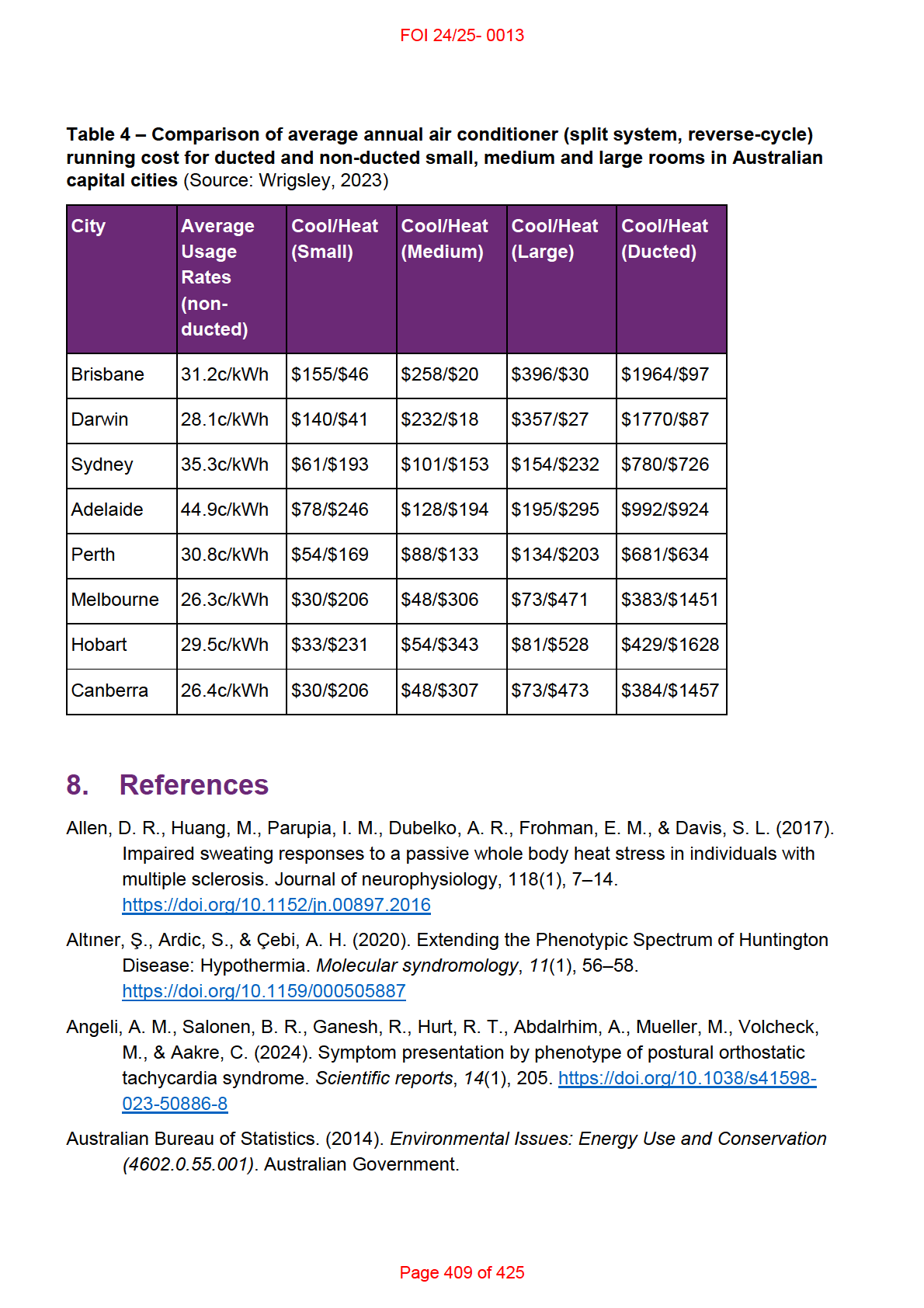

The main types of cooling systems found in Australian homes are fans, evaporative and

refrigerative air conditioners. Refrigerative air conditions, including reverse cycle air

conditioners, are the most common type of air conditioner used in Australia. The cost-

effectiveness of cooling systems depends on several factors including climate, location, energy

prices, architectural features of the home, device running time, temperature set-point and other

lifestyle factors.

There is evidence for the benefits of air conditioner use in the general population to manage

the effects of heat, especially in very hot and dry climates. However, there is very little

evidence comparing air conditioning with other cooling devices or strategies and very little

experimental evidence showing the circumstances in which air conditioning might contribute to

managing the symptoms of thermoregulation impairment.

Despite this, public health messaging and recommendations from researchers and clinicians

are consistent. They suggest that simple behavioural strategies and easily accessible cooling

devices have a role in managing the symptoms of thermoregulation impairment. Behavioural

strategies include:

• understanding personal heat tolerance and preferences

• staying inside during the hotter times of day

• planning outdoor or strenuous activities for cooler times of day

• wearing loose or light clothing

• wearing wet clothes or wraps

• taking regular breaks from activity

• consuming cold foods and drinks

• taking cold baths or showers.

Recommended equipment or devices include:

• space coolers (including evaporative coolers and air conditioning)

• electric fans

• cooling garments.

Page 393 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

3. Human thermoregulation

Humans are homeothermic animals, which means that human body temperature is maintained

at a nearly constant level largely, but not entirely, independent of the environment. Core

human body temperature is maintained at around 37°C (+/- 0.5°C), while peripheral body

temperature may vary more widely (Romanovsky, 2018; Cheshire, 2016).

When the core body temperature is too low, this is called hypothermia. When the core body

temperature is too high, this is called hyperthermia. Some sources refer to hypo and

hyperthermia as any variation outside the normal range of core body temperature.

(Romanovsky, 2018). Other sources define states more specifically as below 35°C for

hypothermia and above 40°C for hyperthermia (Cheshire, 2016).

Slight changes outside the accepted range can be controlled with physiological or behavioural

responses. Extreme changes to core body temperature may lead to significant injury or death

(Osila et al, 2023; Cheshire, 2016). Age can affect the ability to regulate body temperature due

to both physiological changes (such as changes in metabolism or the cardiovascular system)

and behavioural changes (spending more time at home, reduced activity), which is why older

people are more susceptible to complications from environmental extremes (Osila et al, 2023;

Bennetts et al, 2020).

Thermoregulation is the process of maintaining body temperature by balancing heat

generation and heat loss. Temperature variations are picked up by thermoreceptors on the

skin or inside the body. These receptors alert the thermoregulatory centre located in the

hypothalamus to enact thermoeffectors, physiological or behavioural responses that regulate

body temperature.

3.1 Thermoeffectors

Physiological thermoeffectors are involuntary body processes that help to control heat loss or

heat generation. They include:

• skin vasodilation or vasoconstriction

• sweating

• shivering

• piloerection

• panting.

Behavioural thermoeffectors are voluntary or instinctual complex behaviours. They include

behaviours such as changing posture, drinking water, adding or removing clothing, turning on

a fan or air conditioning etc (Osila et al, 2023; Romanovsky, 2018).

Thermoeffectors aid in heat loss, conservation or generation by affecting one or more of the

four processes of heat exchange: conduction, convection, radiation, and evaporation (Osila et

al, 2023; Romanovsky, 2018; Cheshire, 2016).

Page 394 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

Conduction

Conduction occurs when heat is transferred from one object to another object in direct contact.

Materials with high conductivity are more able to draw heat away from the body. For example,

water has a high conductivity and so submersion in water is a good way to draw heat from the

body (Osila et al, 2023; Romanovsky, 2018).

Convection

Convection occurs when a body is submerged in a gas or liquid. Movement of the fluid

replaces layers of fluid closer to the body with fluid further from the body. The layers of fluid

closer to the body have a temperature closer to the temperature of the skin, while the more

distant fluid has a temperature closer to the ambient temperature. Convection therefore

intensifies conduction. If the environment is hotter, the body is exposed to hotter material and

so heats up faster. If the environment is colder, the body is exposed to colder material and so

cools down faster. For example, a ceiling fan cools by convection by increasing movement of

air on the skin, removing warmer air closer to the body and replacing it with cooler air further

from body (Osila et al, 2023; Romanovsky, 2018).

Radiation

All materials emit and absorb heat via radiation in the form of electromagnetic waves. The

human body loses approximately 60% of its heat via radiation. Unlike conduction or

convection, radiation does not require contact with a medium. For example, solar radiation can

warm the earth despite passing through colder layers of earth’s atmosphere (Osila et al, 2023;

Connor, 2022; Romanovsky, 2018; Cheshire, 2016).

Evaporation

Liquid requires energy in the form of heat to evaporate. The heat required is drawn from the

environment or from the liquid itself and transferred from the liquid to the gas. For example,

animals make use of evaporative cooling in the form of sweating and panting (Osila et al,

2023; Romanovsky, 2018; Lohner, 2017). Evaporation accounts for about 22-30% of heat lost

from the body (Osila et al, 2023; Cheshire, 2016). Evaporation is the most efficient form of

heat loss in the human body, though it can be less effective in more humid environments and

does consume large amounts of water. Evaporation is the only form of heat transfer that also

works when the ambient temperature is higher than the temperature of the skin (Romanovsky,

2018).

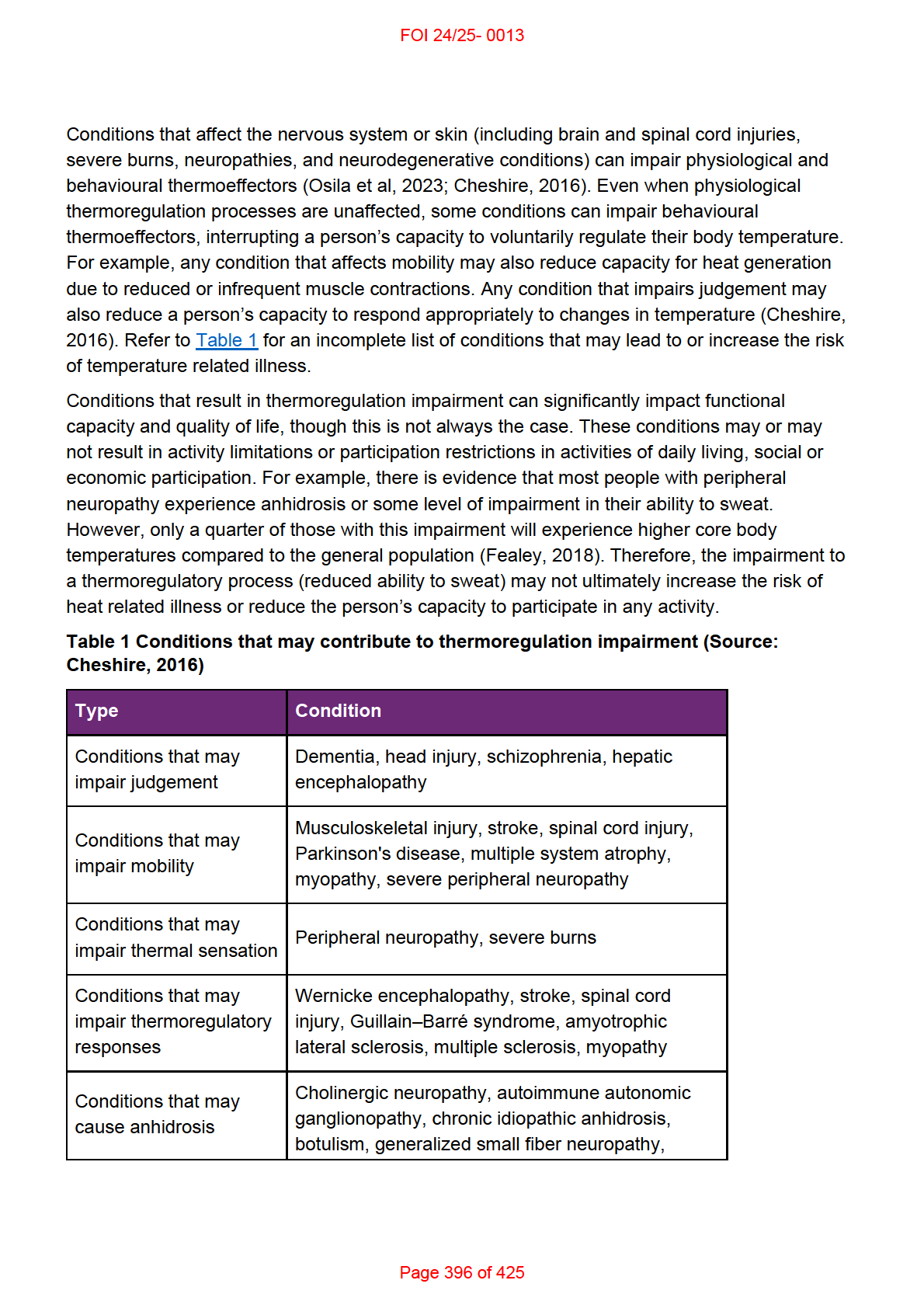

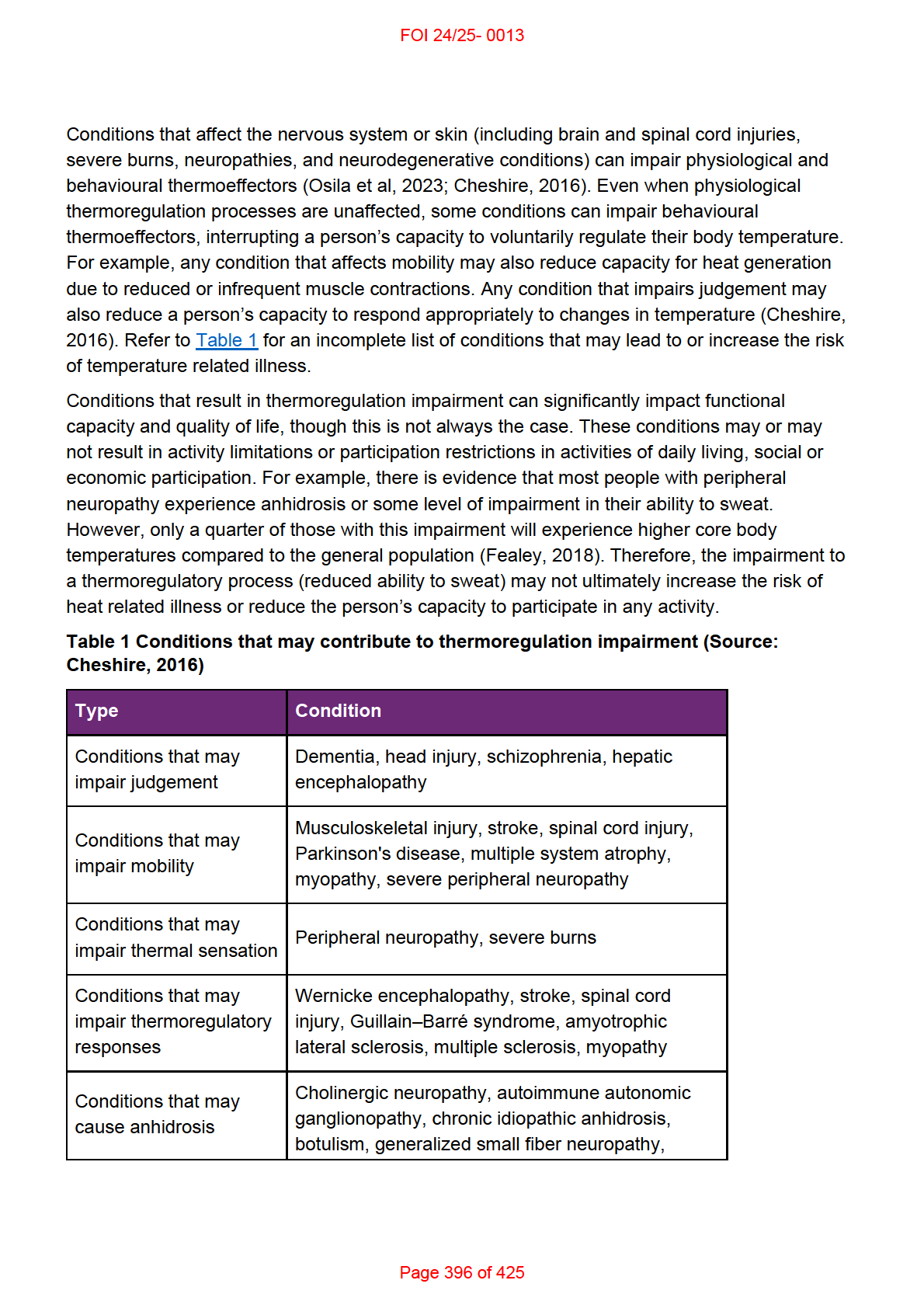

4. Conditions resulting in thermoregulation impairment

Some conditions can impair our thermoregulatory processes and therefore increase the risk of

temperature related health problems. The sections below describe some, though not all,

conditions for which there is evidence of thermoregulatory impairment. For most conditions,

whether thermoregulation impairment occurs, or whether the impairment is substantial and

results in activity limitations or participation restrictions, will vary for individuals.

Page 395 of 425

FOI 24/25- 0013

Sjögren syndrome, multiple system atrophy,

Fabry's disease, bilateral cervical sympathectomy

Conditions that may

Status epilepticus, neuroleptic malignant

increase thermogenesis syndrome, malignant hyperthermia

Other conditions that

Hypoglycemia, Diabetic ketoacidosis,

may lead to

Hypothyroidism, Adrenal failure, Hypopituitarism,

thermoregulatory

Renal failure, Shock, Sepsis, Anorexia nervosa,

impairment

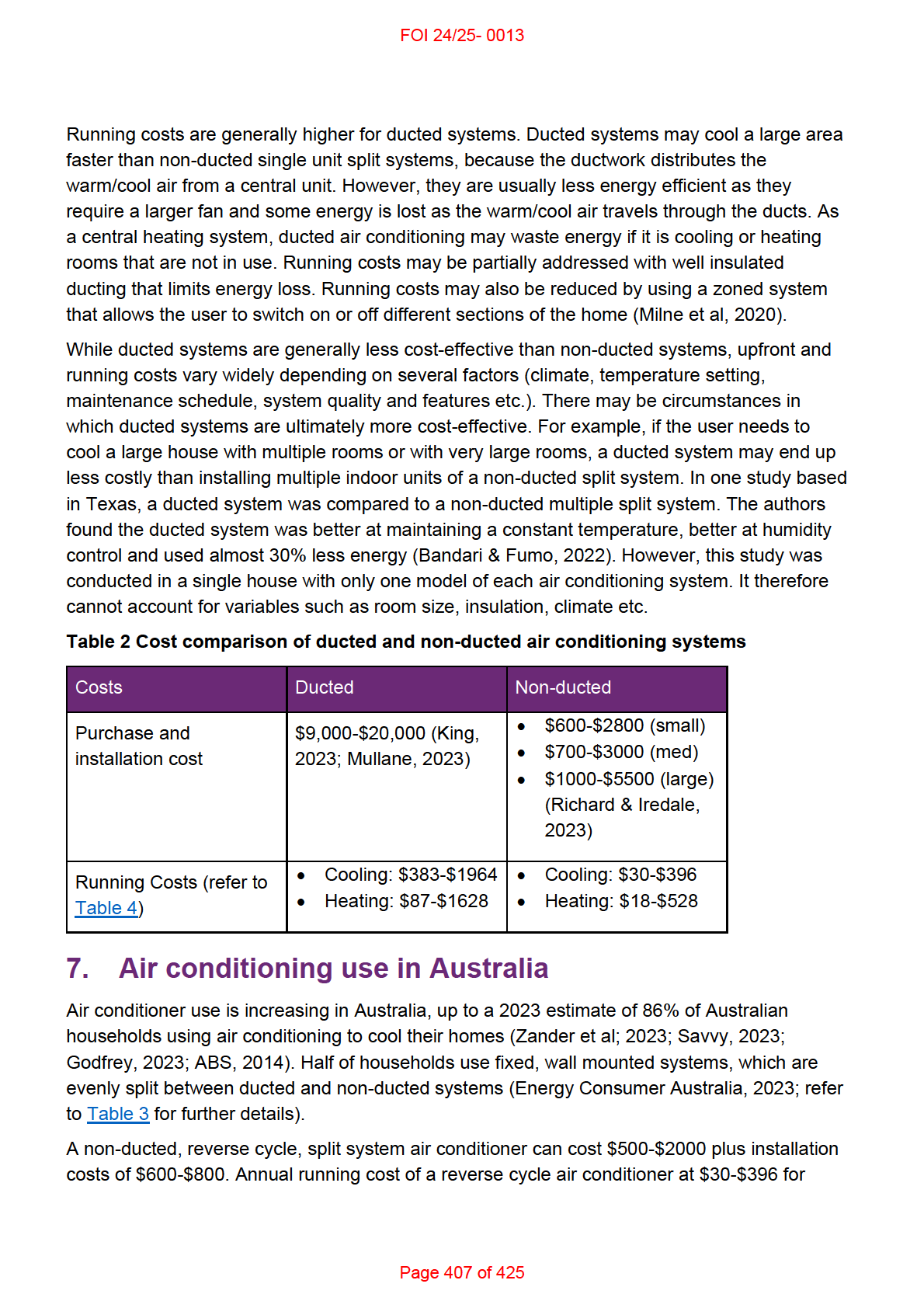

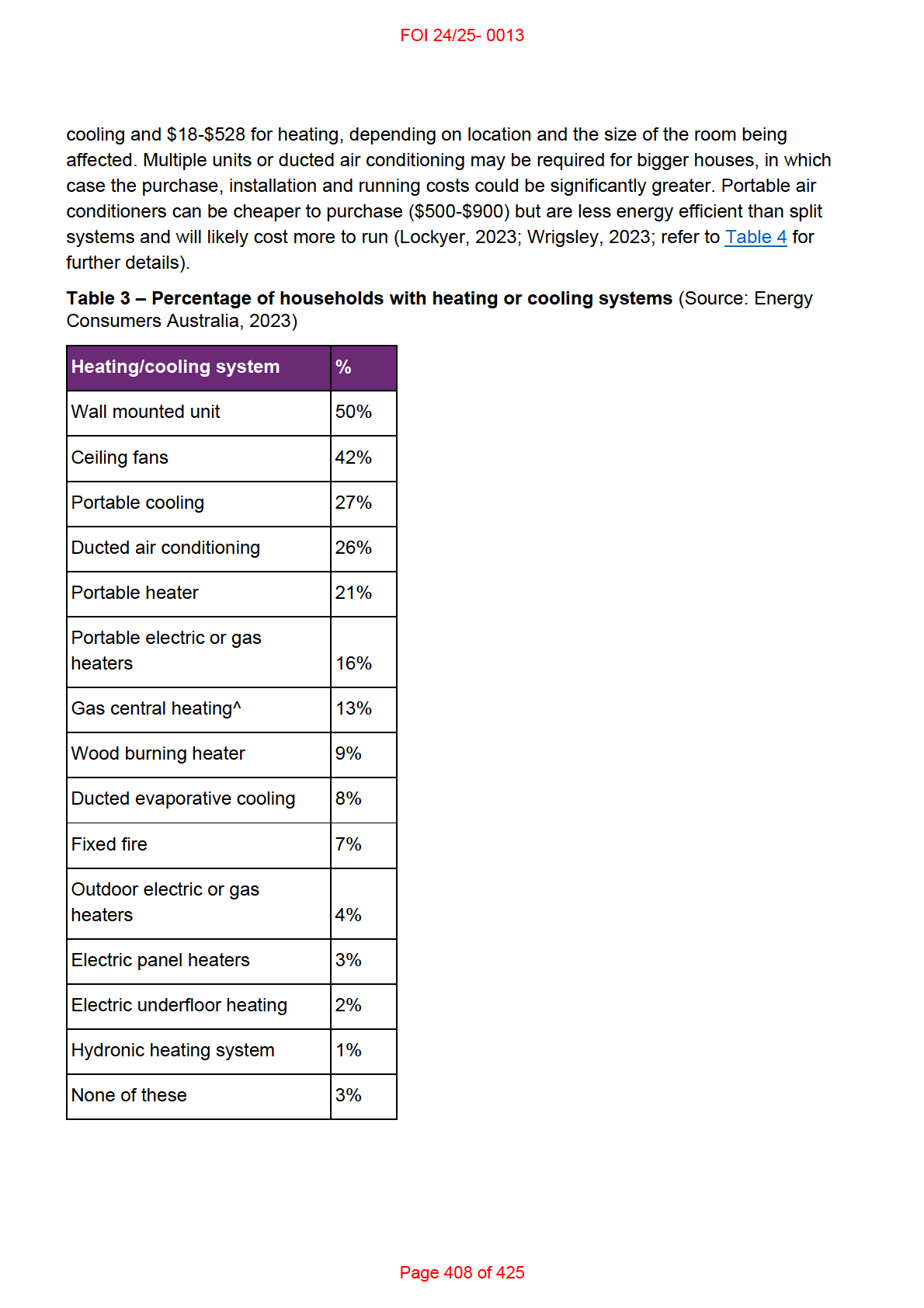

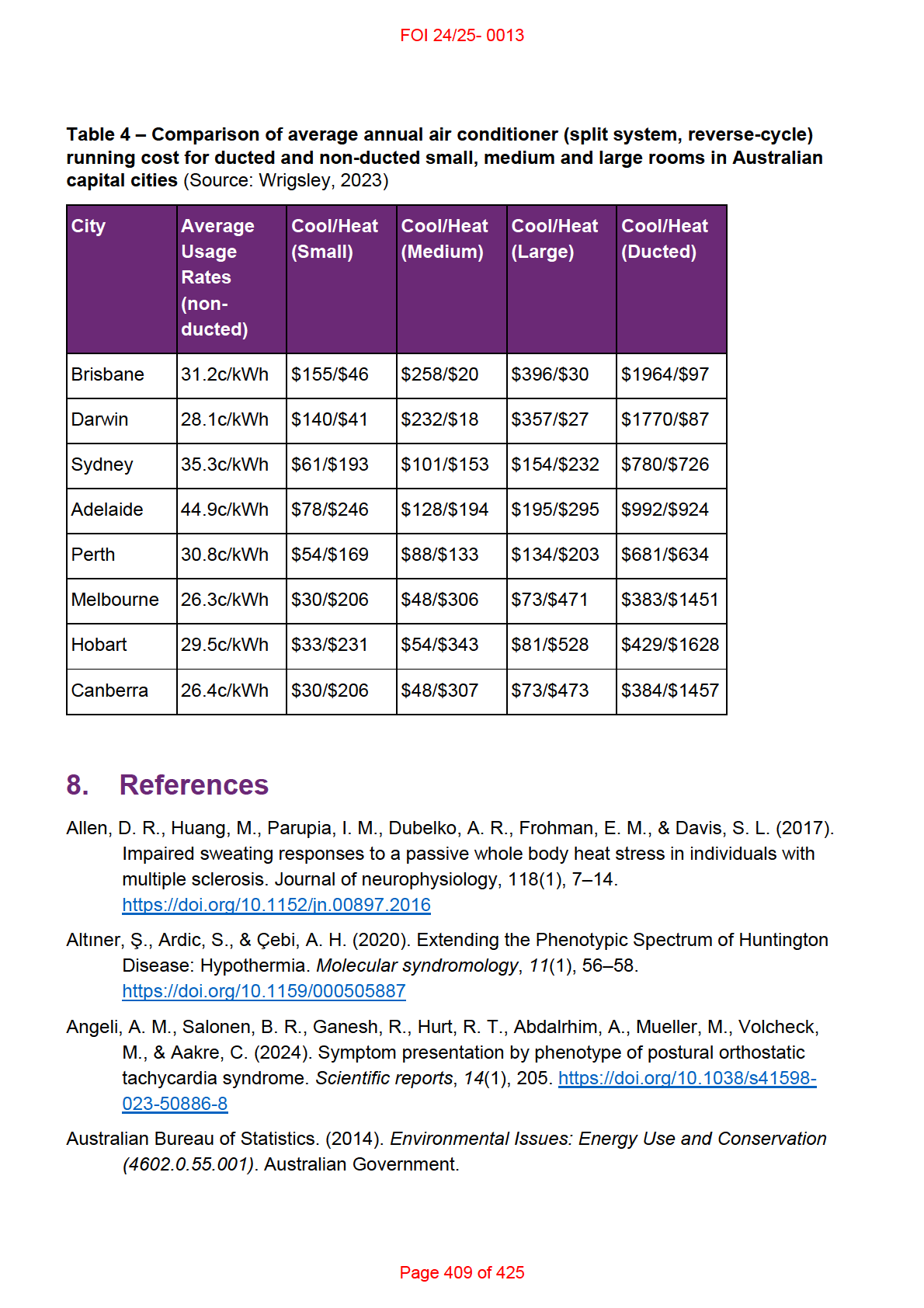

Thyrotoxicosis, Pheochromocytoma