FOI 5155 - Document 1

s47G

response to MSAC CA 1530

Purified human alpha1-proteinase inhibitor

1. “Minimum clinically important differences for the primary outcome in the core randomised

controlled trials (RCTs), i.e. Computed tomography (CT)-measured lung density, are not established

in the literature…” [MSAC CA 1530, p1]

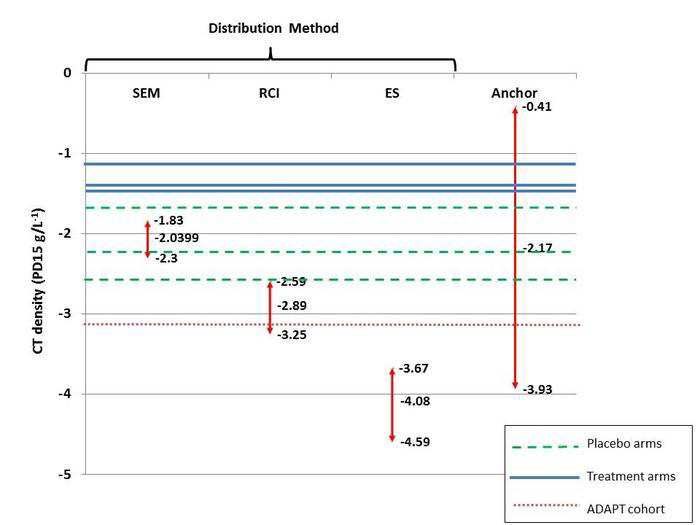

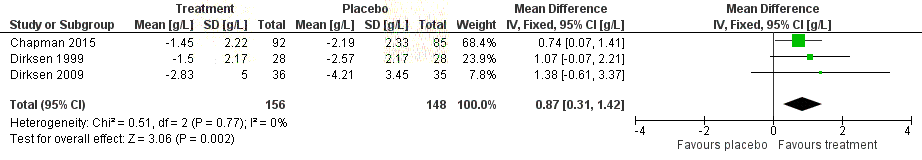

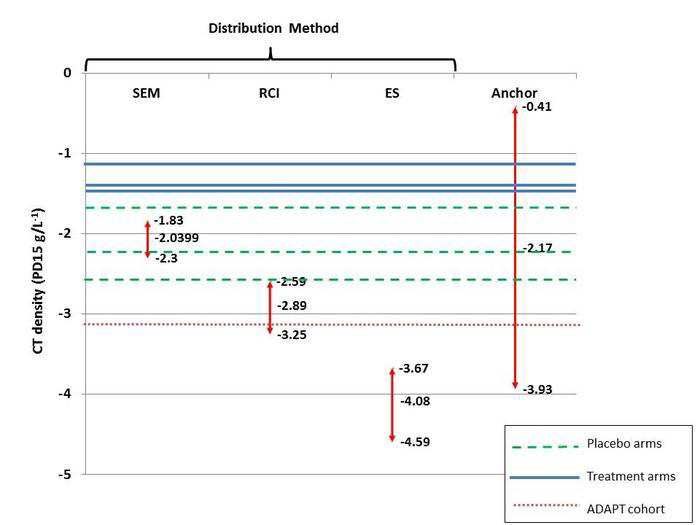

Lung CT densitometry changes have proven to be the most sensitive marker of disease progression in

patients with A1PI deficiency and COPD as compared to pulmonary function tests or quality of life

assessments (Dirksen 2009, Chapman 2015). However, in absence of an established minimum

clinically important difference (MCID) for lung density decline rates, the results seen in the RAPID and

EXACTLE trials may be difficult to interpret. To help address this issue, a group of renowned A1PI

researchers in Birmingham, UK are currently working to establish the MCID based on the CT density

outcomes from the placebo-controlled trials (Dirksen 1999, Dirksen 2009, Chapman 2015). The

researchers recently proposed an MCID of -2.89 g/L (95% CI: -2.59, -3.25) at the American Thoracic

Society conference held in May 2018 (Crossley et al 2018).

the

Based on the annual preservation of lung tissue (0.74 g/L/year) demonstrated in the RAPID trial in

favor of A1PI therapy, the proposed MCID would be achieved within 3.9 years as compared to an

under

(CTH) Care.

untreated patient. As the treatment effect was robust and largely consistent between the RAPID and

RAPID OLE trials in the Early Start patients who received 4-years of weekly infusions, a patient

continuously treated with A1PI 60 mg/kg each week can reasonably expect to maintain a reduced rate

1982 Aged

of lung density decline well beyond the point at which the proposed MCID has been reached,

released

demonstrating a worthwhile clinical improvement in this rare and often fatal disease.

Act and

2. “No significant differences were observed between A1PI and placebo for the remaining

been

effectiveness outcomes.” [MSAC CA 1530, p1]

has

Health

Demonstrating clinical efficacy in A1PI deficiency leading to COPD is challenging. It requires

of

quantitative documentation of lung function changes in a chronic and slowly progressive process that

Information

may take decades to manifest clinically (Wewers and Crystal 2013). Despite showing a significant

of

effect on lung density, the RAPID study did not show any statistical signal of efficacy in the secondary

endpoints.

document

There are several possible reasons for this: First, and importantly, the study was powered to detect

Department

the treatment effect on lung density measures, not changes in pulmonary function tests, diffusion

This Freedom

capacity of carbon monoxide (DLco), Incremental Shuttle Walking Test (ISWT), or St. George’s

the

Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) scores. The sample size and trial duration reflect those necessary

to demonstrate an effect to slow the annual lung density rates, whereas it has been shown that

by

significantly more patients followed for periods longer than 2 years would be required to investigate

benefits of A1PI therapy in the secondary endpoints. Furthermore, those estimates are based on the

use of placebo which would be considered unethical for the treatment of A1PI deficiency. Secondly,

the sensitivity of the clinical endpoints to detect change is much lower compared to CT lung density;

EXACTLE, the second largest study in A1PI deficiency, established CT scans and DLco as the most

sensitive measures.

s47G

COMMERCIAL-IN-CONFIDENCE

1

Page 1 of 3

FOI 5155 - Document 1

s47G

response to MSAC CA 1530

Purified human alpha1-proteinase inhibitor

3. “A1PI meets three of the four criteria warranting rule of rescue. It is unclear whether the proposed

service provides worthwhile clinical improvement.” [MSAC CA 1530, p146]

s45

The recent work by Crossley et al to describe

the MCID for CT density decline provides further clinical context for the results seen in the RAPID trial,

and further demonstrates that A1PI offers worthwhile clinical improvement when evaluated across

the appropriate time horizon, noting that A1PI deficiency is a chronic and slowly progressive disease.

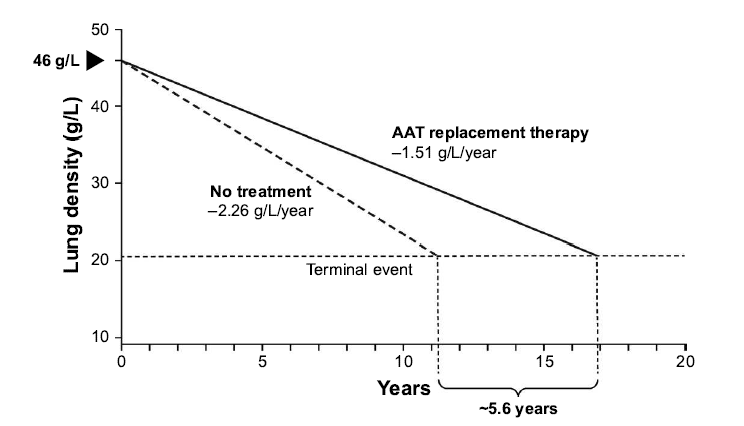

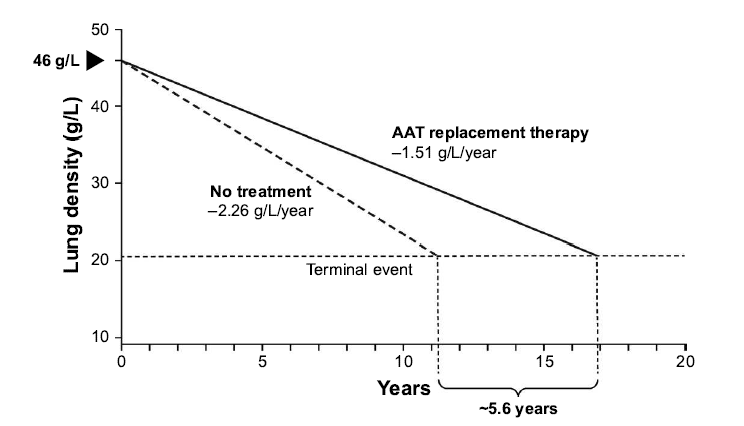

Furthermore, evidence from a post hoc analysis of the RAPID programme suggests a mortality benefit

following A1PI therapy. During the RAPID programme, the time required for progressive emphysema

to develop into respiratory crisis was used to simulate the life-years gained as a result of A1PI therapy.

the

Respiratory crisis was defined as death, lung transplant or a crippling respiratory condition. Seven

patients withdrew with an average terminal lung density of 20 g/L. Using the average baseline lung

density for all patients (46 g/L) and the rate of decline in lung density in A1PI versus placebo-treated

under Care.

patients, the projected time to terminal lung density was 16.9 years for those receiving A1PI therapy,

(CTH)

compared with 11.3 years in the placebo group (Figure 1). This indicates a gain in life-years of 5.6 years

with A1PI therapy (McElvaney et al 2017). Although conducted in a small sample size, these data are

1982 Aged

supported by results from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute observational study showing

released

that patients receiving A1PI therapy had a greater survival than those not receiving treatment (Alpha-

Act and

1-Antitrypsin Deficiency Registry Study Group, 1998).

been

Figure 1

Extrapolation of the effect of A1PI replacement therapy on the predicted time to

reach terminal respiratory function in RAPID-RCT.

has

Health

Information

of

of

document

This Freedom

Department

the

by

Source: Chapman et al 2018

International Journal of COPD 18(13): 419-432

No comments on the economic evaluation or financial implications are provided in this response as

Section C, D, E were redacted from the report provided to s47G

due to the commercial in

confidence nature of the material.

s47G

COMMERCIAL-IN-CONFIDENCE

2

Page 2 of 3

FOI 5155 - Document 1

s47G

response to MSAC CA 1530

Purified human alpha1-proteinase inhibitor

REFERENCES

Alpha-1-Antitrypsin Deficiency Registry Study Group (1998). Survival and FEV1 decline in individuals

with severe deficiency of alpha1-antitrypsin. The Alpha-1-Antitrypsin Deficiency Registry

Study Group,

Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 158(1), pp. 49-59.

Chapman, K., Burdon, J., Piitulainen, E., Sandhaus, R., Seersholm, N., Stocks, J., Stoel, B., Huang, L.,

Yao, Z., Edelman, J. & McElvaney, N. (2015). Intravenous augmentation treatment and lung

density in severe Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (RAPID): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-

controlled trial,

Lancet 386(9991), pp. 360-368

Chapman, K. R., Chorostowska-Wynimko, J., Rembert Koczulla, A., Ferrarotti, I., & McElvaney, N. G.

(2018). Alpha 1 antitrypsin to treat lung disease in alpha 1 antitrypsin deficiency: recent

the

developments and clinical implications.

Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 13: 419–432.

Crossley, D., Subramanian, D., Stockley, R. A., & Turner, A., M. (2018). Proposal and validation of a

under

minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for annual pulmonary CT density decline.

(CTH) Care.

American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 197:A3905

Dirksen, A., Dijkman, J. H., Madsen, F., Stoel, B., Hutchison, D. C., Ulrik, C. S., Skovgaard, L.T., Kok-

1982 Aged

Jensen, A.,Rudolphus, A., Seersholm, N., Vrooman, H. A., Reiber, J. H., Hansen, N.C.,

released

Heckscher, T., Viskum, K. & Stolk, J. (1999). A randomized clinical trial of alpha(1)-antitrypsin

Act and

augmentation therapy,

Am J Respir Crit Care Med 160 (5 Pt 1), pp. 1468-1472.

been

Dirksen, A., Piitulainen, E., Parr, D.G., Deng, C., Wencker, M., Shaker, S.B. & Stockley, R.A. (2009).

Exploring the role of CT densitometry: a randomised study of augmentation therapy in alpha1-

has

Health

antitrypsin deficiency.

Eur Respir J 33(6), pp. 1345-1353.

Information

of

McElvaney, N.G., Burdon, J., Holmes, M., Glanville, A., Wark, P. A., Thompson, P. J., Hernandez, P.,

of

Chlumsky, J., Teschler, H., Ficker, J. H., Seersholm, N., Altraja, A., Makitaro, R., Chorostowska-

Wynimko, J., Sanak, M., Stoicescu, P. I., Piitulainen, E., Vit, O., Wencker, M., Tortorici, M. A.,

Fries, M., Edelman, J. M & Ch

document apman, K. R. (2017). Long-term efficacy and safety of alpha1

proteinase inhibitor treatment for emphysema caused by severe alpha1 antitrypsin

Department

deficiency: an open-label extension trial (RAPID-OLE), Lancet Respir Med, 5(1), pp. 51-60.

This Freedom

the

Wewers, M. D., & Crystal, R. G. (2013). Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Augmentation Therapy. COPD: Journal of

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 10(S1): 64-67

by

s47G

COMMERCIAL-IN-CONFIDENCE

3

Page 3 of 3

FOI 5155 - Document 1.1

12

45678

9

4

5

7

656

595

!"

#

$""

!%

&!%'()

&(

*+

,-

+.

/&0

1-

+.

&

/#

2

3

45

/0

6*)

7#

!8%'

295

:

0

$%

;

<!

=!%9%

!%

=%

#

6>?@?ABC

BDE

FBC

G

EBHG

?D

?I

B

G

DG

JBC

4C

G

DG

KBC

C

L

J@?>H

BDH

7G

I

IM>MDKM

N4

7O

I

?>

DDPBC

6PC

J?DB>L

4

7MDAG

HL

7MKC

G

DM

;Q

=#

!""5

(+)

;Q

$8R#

%

%*)

SQ

/Q

$

!T5

(U)

/Q

&Q

8#

%#

1V

+/;/

!W

)

X%

9#

"

(

4!"Y

5

"

6

#

%<)

6

#

%<)

X%

'

Z

%<'!)

*S!(5

;#

R(

4!"Y

5

)

;#

R()

X%

'

Z

%<'!)

U28%<

[

%9"

<

!%

X%

)

\8%

]5

^R

4!"Y)

6

#

%<)

X%

'

Z

%<'!)

1/;/

!W

)

\8%

]5

^R

4!"Y

5

)

6

#

%<)

X%

'

Z

%<'!Qthe

4?>>MA@?DEG

D_

BPH

`?>a

A

MJBG

C

8

EG

BDBb

K>?AAC

MLcdD`Ab

DMH

S

!%5

-

=!Y8

'

!!<#

Y(

3

=:

'%"

!

#

(

"

R%

8"'

"

Y#

#

(

!8

!

under

"8#

%

"9#

5

S%'!

"'

Y5

R!

=!%

#

!5'

#

5

"

3

S=":

!W

/5

Y

!%

/

(CTH) 8<%

Care. !%

#

Y(

3

//:

!

""""

5

!#

!%

!W

5

8%<

'%"

(

'5

%Q

/%

&=[

;

W

!#

=

'%"

(

e!85

'

Y#

!9

'

!#

5

#

(

!W

'%"

(

%<"

%(

Y#

9

"

9

%<

8%#

%

5

%

5

Y

Q

#

#

e!

#

!<%

"'

!'"

W

!#

Y#

!Y!"

%<

%

&=[

;V

%5

(

1982 %!#%

Aged ''"#R8!%

!'Q

f

!

'

#

%

%'

95

'

%

&=[

;

W

!#

=

'%"

(

released '5%%Y%"e//;

8"

%<

R!

#

!<%

"'

!'"Q

"

e!85

'

5

#

W

(

W

!W

Act //)%

and '!#!'%W(!"

Y

%

"

e

"

<%

W

%

'5

%

e!

(

%'

%

#

9%

!%Q

&

!'"-

g!#

'

"

#

R8

!%

!')

been

"

8'

"

e#

"!8<

#

Y!#

'

%

%'

"

%'#

'

'9

!%

!W

=

'%"

(

3

"

"8#

'

R(

+.

#

%

5

!

%

V

;+.

<

2:

R"5

%

%'

e

%%85

%<Q

"

e#

%

8"'

!

has

Health

5

85

&=[

;

8"

%<

U

9#

!%"

!W

'

"

#

R8

!%

!'-

"

%'#

'

#

#

!#

!W

of

"8#

%

3

$]&:

)

#

5

R5

%<

%'h

3

S=[

:

)

%'

W

"

^

3

]$:

Q

g!#

%!#

Information

!')

%(

YY#

"

#

Y!#

'

%%85

=

'%"

(

%<

e

#

5

9

%<

%

g]i+

"

of

"8#

'

%

5

"

e

!8

hY!"8#

!

%

%

#

9%

!%

3

Y5

R!

#

":

e#

#

9

e'Q

&=[

;

e"

%

95

'

'

8"

%<

6

#

%<

//

!!#

Q

%

"

e!

'

#

9'

e!

!#

!#

=

"%"

Y5

8"

5

"

#

g]

document i+"8#%"!9#5"#(#"e#'%W'Q

/%%85

"5

!Y

g]i+

3

5

":

e"

5

85

'

%'

!Y#

'

e

#

"Y

9

%%85

=

'%"

(

Department

%<

%'

!Y#

This 'R(5%##<#""!%%5(""QS"85"-g<8#!%58"#"&=[;

Freedom

%'

#

!%W

'%

%

#

95

"Q

!%W

'%

%

#

95

"

W

#

!

%!#

!'

%!Y""'

the

!"

!W

$]&

%'

S=[

Q

7

9%

Y#

!Y!"'

&=[

;

"!85

'

!#

<

%

W

#

!

9#

(

!W

!'")

"

#

"!%R5

by !Y#!Y!"&=[;W!#='%"("0*Qj,<2"""''5

"

W

#

!

#

'

"

#

R8

!%

!'")

%'

"

5

e

%

!%W

'%

%

#

95

"

!W

%!#

!'Q

=!%5

8"

!%-

Y#

!Y!"'

&=[

;

W

!#

=

'%"

(

%

Y

%

"

e

//;

"

0

*Q

j,<

2Q

i5

8"

%

h""

!W

"

%

Y

%

"

8%'#

"8#

9

5%

e!85

'

%'

#

Y

'

'%"

(

'5

%)

e

(

R

!%

%'

!%

W

!#

//

8<%

!%

#

Y(Q

Page 1 of 2

FOI 5155 - Document 1.1

the

under

(CTH) Care.

Aged

released 1982

Act and

been

has

Health

12

3

5637

8

597

2

3

6

2

3

2

7

157

2

93

Information

of

! "#$%&'()

'*+,

-*&.

/

0!

0!"$$,1112

"!

3

450"6

2

47

806

09!

":!

/

5

of

document

This Freedom

Department

the

by

Page 2 of 2

FOI 5155 - Document 2

14 September 2018

s47G

response to MSAC Contracted Assessment 1530

Overall, the need for treatment of patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (AATD), as well as the

clinical evidence for augmentation therapy with alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor (A1PI), is well summarised

in the Assessment Report.

With respect to the findings, s47G notes that the Assessment Report concluded that for the outcome

of computed tomography (CT)-lung density, a statistically significant treatment effect was observed.

Given that the aim of treatment with A1PI is to slow the rate of decline in lung function, improve quality

of life and extend the patient’s life-expectancy, this is a critically important finding. Indeed, the

Assessment Report concurred with s47G submission that there is evidence supporting a correlation

between CT-lung density decline, mortality and functional outcomes. While s47G acknowledges the

uncertainty around the magnitude of the benefit, large randomised clinical trials are required to provide

more accurate estimates. Due to the rarity of AATD, this is no longer ethically possible with the

availability of A1PI therapies that are bioequivalent (i.e. Prolastin-C and Zemaira). Nonetheless, based

on the totality of the clinical evidence, it is reasonable to expect that treatment with A

the 1PI will slow rate

of decline in lung function, improve quality of life and survival in Australian clinical practice.

With interest, s47G notes the Consumer Impact Statement from the foundation for patients with

under

AATD which highlights its intention to establish an Australian register for patients to better understand

(CTH) Care.

the epidemiology of the disease if the A1PI therapies are funded through the NBA. In addition to the

other consumer impact statements regarding the need for therapies with a demonstrated clinical

benefit in AATD, s47G welcomes the thorough consideration of the Rule of Rescue in the Assessment

1982 Aged

Report including the acknowledgements that there is currently no treatment for patients with AATD, as

well as the small number of patients that suffer from this severely de

released bilitating disease that is associated

with significant reduction in survival.

Act and

s47G

been

has

Health

Information

of

of

document

This Freedom

Department

the

by

Page 1 of 1

FOI 5155 - Document 3

s47F

s47F

s47F

s47F

s47F

s47G

the

under

(CTH) Care.

Aged

released 1982

Act and

been

s47G

s47G

has

Health

Information

of

s47G

of

s47G document

This Freedom

Department

the

s47F

by

s47F

s47F

s47F

s47G

Page 7 of 12

FOI 5155 - Document 3

s47F

s47F

s47F

s47G

s45

s45

s47F

the

s47G

under

s47G(CTH) Care.

Aged

released 1982

s47F

Act and

been

s47G

has

Health

Information

of

of

document

s47F

This Freedom

Department

s47F

the

s47F

s47F

by

s47F

s47G

s47G

Page 9 of 12

FOI 5155 - Document 3

s47G

s47G

s47F

s47F

s47F

s47F

the

under

(CTH) Care.

Aged

released 1982

Act and

been

s47G

s47G

has

Health

Information

of

of

document

This Freedom

Department

the

by

Page 10 of 12

FOI 5155 - Document 3

s47G

s47G

s47G

the

under

s47G

(CTH) Care.

Aged

released 1982

Act and

been

s47G

has

Health

Information

of

of

s47G

s47G

document

s47G

This Freedom

Department

the

by

s47G

s47G

Page 11 of 12

FOI 5155 - Document 3

s47G

the

under

(CTH) Care.

s47G

Aged

released 1982

Act and

s47G

been

has

Health

Information

of

of

document

This Freedom

Department

the

by

s45,

s47G

s47G

s45, s47G

s45,

s45, s47G

s47G

s45, s47G

s47G

s47G

Page 12 of 12

FOI 5155 - Document 3.1

the

under

(CTH) Care.

Aged

released 1982

Act and

been

has

Health

Information

of

of

document

This Freedom

Department

the

by

Page 1 of 48

FOI 5155 - Document 3.1

the

under

(CTH) Care.

Aged

released 1982

Act and

been

has

Health

Information

of

of

document

This Freedom

Department

the

by

Page 2 of 48

FOI 5155 - Document 3.1

the

under

(CTH) Care.

Aged

released 1982

Act and

been

has

Health

Information

of

of

document

This Freedom

Department

the

by

Page 3 of 48

FOI 5155 - Document 3.1

the

under

(CTH) Care.

Aged

released 1982

Act and

been

has

Health

Information

of

of

document

This Freedom

Department

the

by

Page 4 of 48

FOI 5155 - Document 3.1

the

under

(CTH) Care.

Aged

released 1982

Act and

been

has

Health

Information

of

of

document

This Freedom

Department

the

by

Page 5 of 48

FOI 5155 - Document 3.1

the

under

(CTH) Care.

Aged

released 1982

Act and

been

has

Health

Information

of

of

document

This Freedom

Department

the

by

Page 6 of 48

FOI 5155 - Document 3.1

the

under

(CTH) Care.

Aged

released 1982

Act and

been

has

Health

Information

of

of

document

This Freedom

Department

the

by

Page 7 of 48

FOI 5155 - Document 3.1

the

under

(CTH) Care.

Aged

released 1982

Act and

been

has

Health

Information

of

of

document

This Freedom

Department

the

by

Page 8 of 48

FOI 5155 - Document 3.1

the

under

(CTH) Care.

Aged

released 1982

Act and

been

has

Health

Information

of

of

document

This Freedom

Department

the

by

Page 9 of 48

FOI 5155 - Document 3.1

the

under

(CTH) Care.

Aged

released 1982

Act and

been

has

Health

Information

of

of

document

This Freedom

Department

the

by

Page 10 of 48

FOI 5155 - Document 3.1

the

under

(CTH) Care.

Aged

released 1982

Act and

been

has

Health

Information

of

of

document

This Freedom

Department

the

by

Page 11 of 48

FOI 5155 - Document 3.1

the

under

(CTH) Care.

Aged

released 1982

Act and

been

has

Health

Information

of

of

document

This Freedom

Department

the

by

Page 12 of 48

FOI 5155 - Document 4

Purified human

alpha1-proteinase

inhibitor for the

treatment of alpha1-

proteinase inhibit

the

or

deficiency, leading

to chronic

under

(CTH) Care.

obstructive

pulmonary disease

1982 Aged

released

Act and

been

has

Health

Au

of

gust 2018

Information

of

document

MSAC application no. 1530

This Freedom

Department

the

Assessment report

by

Page 1 of 218

FOI 5155 - Document 4

© National Blood Authority 2018

Internet site http://www.msac.gov.au/

This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only

(retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any

use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, al other rights are reserved. Requests and inquiries

concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to Commonwealth Copyright Administration,

Attorney-General's Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton ACT 2600 or posted at

http://www.ag.gov.au/.

Electronic copies of the report can be obtained from the Medical Service Advisory Committee’s Internet site at

http://www.msac.gov.au/

the

Enquiries about the content of the report should be emailed to xxx@xxxxxx.xxx.xx.

The technical information in this document is used by the Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC) to

inform its deliberations. MSAC is an independent committee that has been established to provide advice to

under

the Minister for Health on the strength of evidence available on new and existing medical technologies and

(CTH) Care.

procedures in terms of their safety, effectiveness and cost effectiveness. This advice wil help to inform

government decisions about which medical services should attract funding under Medicare.

1982 Aged

MSAC’s advice does not necessarily reflect the views of al individuals who participated in the MSAC

released

evaluation.

Act and

This report was prepared by Research and Evaluation, i

been ncorporating ASERNIP-S of the Royal Australasian

Col ege of Surgeons, and eSys Development Pty Limited. The report was commissioned by the Australian

Government Department of Health.

has

Health

of

The suggested citation for this document is:

Information

of

Vreugdenburg TD, Scarfe AJ, Ma N, Jacobsen JH, McLeod R, Tivey D (2018). Purified human alpha1-proteinase

inhibitor for the treatment of alpha1-proteinase inhibitor deficiency, leading to chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease. MSAC Application 1530, Assessm

document ent Report. Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, ACT.

This Freedom

Department

the

by

Alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor augmentation – MSAC CA 1530

ii

Page 2 of 218

FOI 5155 - Document 4

CONTENTS

Contents

............................................................................................................................. iii

Tables ....................................................................................................................................... v

Boxes ....................................................................................................................................... x

Figures .................................................................................................................................... xi

List of terms ........................................................................................................................... xiii

Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 1

Alignment with agreed PICO Confirmation .............................................................................

the

2

Proposed medical service ........................................................................................................ 2

Proposal for public funding ..................................................................................................... 2

under Care.

Population ...............................................................................................................................

(CTH)

2

Comparator details .................................................................................................................. 2

Clinical management algorithm(s) ..........................................................................................

1982 Aged

3

released

Clinical claim ............................................................................................................................ 3

Act and

Approach taken to the evidence assessment .......................................................................... 3

been

Characteristics of the evidence base ....................................................................................... 3

Results ..................................................................................................................................... 3

has

Health

Translation issues .................................................................................................................... 6

Information

of

Economic evaluation ............................................................................................................... 6

of

Estimated extent of use and financial implications ................................................................. 8

Consumer impact summary .................................................................................................... 9

document

Other relevant considerations ................................................................................................. 9

Department

Section A

Cont

This

ext ................................................................................................................ 10

Freedom

A.1. Items in the ag

the reed PICO Confirmation .................................................................... 10

A.2. Propose

by d medical service ......................................................................................... 10

A.3. Proposal for public funding ....................................................................................... 13

A.4. Proposed population ................................................................................................. 13

A.5. Comparator details ................................................................................................... 16

A.6. Clinical management algorithm ................................................................................ 17

A.7. Key differences in the delivery of the proposed medical service and the

main comparator ................................................................................................................... 20

A.8. Clinical claim.............................................................................................................. 20

Alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor augmentation – MSAC CA 1530

iii

Page 3 of 218

FOI 5155 - Document 4

A.9. Summary of the PICO ................................................................................................ 20

A.10. Consumer impact statement .................................................................................... 21

Section B

Clinical evaluation ................................................................................................ 23

B.1. Literature sources and search strategies .................................................................... 23

B.2. Results of literature search ......................................................................................... 23

B.3. Risk of bias assessment ............................................................................................... 29

B.4. Characteristics of the evidence base........................................................................... 36

B.5. Outcome measures and analysis ................................................................................. 38

Primary effectiveness outcomes ........................................................................................... 38

the

Secondary effectiveness outcomes ....................................................................................... 44

B.6. Results of the systematic literature review ................................................................ 48

Is it safe? ................................................................................................................................ 48

under

(CTH) Care.

Is it effective (RCT evidence)? ............................................................................................... 60

B.7. Extended assessment of harms ................................................................................... 70

1982 Aged

B.8. Interpretation of the clinical evidence ........................................................................ 71

released

Section C

Translation Issues ................................................................................................

Act

. 74

and

C.1. Overview ..................................................................................................................... 74

been

C.2. Applicability translation issues .................................................................................... 74

Health

C.3. Selection of utility value issu

has es ................................................................................... 79

of

C.4. Extrapolation translation issues .................................................................................. 90

Information

C.5 Relationship of each pre-modelling study to the economic evaluation .................... 96

of

Section D

Economic Evaluation ............................................................................................. 98

document

D.1. Overview ................................................................................................................... 98

D.2. Populations and settings ........................................................................................... 99

This Freedom

Department

D.3. Structure and rationale of the economic evaluation .............................................. 101

the

D.4. Inputs to the economic evaluation ......................................................................... 120

by

D.5. Results of the Economic Evaluation ........................................................................ 126

D.6. Sensitivity analyses ................................................................................................. 129

Section E

Financial Implications ......................................................................................... 135

E.1. Justification of the selection of sources of data........................................................ 135

E.1. Costs to the NBA of the proposed therapy over five years....................................... 141

E.2. Changes in use and cost of other medical services ................................................... 141

E.3. Overall financial implications .................................................................................... 142

Alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor augmentation – MSAC CA 1530

iv

Page 4 of 218

FOI 5155 - Document 4

E.4. Identification, estimation and reduction of uncertainty ........................................... 142

Section F

Other relevant considerations ............................................................................. 144

Access considerations .......................................................................................................... 144

Dosing considerations ......................................................................................................... 145

Ethical considerations: Rule of rescue ................................................................................. 146

Appendix A Clinical Experts and Assessment Group ............................................................... 147

Clinical experts consulted during the preparation of this report ........................................ 147

Assessment group ............................................................................................................... 147

Appendix B Search strategies ................................................................................................ 148

the

Appendix C Studies included in the Systematic Review .......................................................... 153

Appendix D Evidence Profile Tables ....................................................................................... 170

under

Appendix E

Care.

Excluded Studies ................................................................................................

(CTH)

. 190

References .......................................................................................................................... 193

Aged

released 1982

T

Act

ABLES

and

been

Table 1

Balance of clinical benefits and harms of A1PI relative to placebo as

measured by the critical patient-relevant outcomes in the key studies ................ 5

has

Health

Table 2

Summary of the economic evaluatio

of n ................................................................... 6

Information

Table 3

Incremental Cost Effectiveness Ratio (1,000-patient cohort) ................................ 7

of

Table 4

Drivers of the economic model .............................................................................. 8

document

Table 5

Total costs to the NBA associated with AT ............................................................. 9

Table 6

Approved augmentation therap

Department ies and their indications .................................... 12

This Freedom

Table 7

Studies evaluating the biocompatability of A1PI therapies ................................. 12

the

Table 8

Serum A1PI levels associated with normal and SZ or ZZ allele variations

by

known to increase the risk of emphysema (Hatipoglu and Stoller 2016) ............ 15

Table 9

Trials (and associated data) presented in the assessment report ....................... 25

Table 10 Details of clinical trials identified on Clinicaltrials.gov ......................................... 27

Table 11 Details of clinical trials identified on EU Clinical Trials Registry ........................... 28

Table 12 Details of clinical trials identified on WHO International Clinical Trials

Registry Platform .................................................................................................. 28

Alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor augmentation – MSAC CA 1530

v

Page 5 of 218

FOI 5155 - Document 4

Table 13 Patient flow in randomised controlled trials ........................................................ 32

Table 14 Key features of the included RCTs comparing A1PI augmentation

therapy with placebo ........................................................................................... 36

Table 15 Key features of the included studies assessing alpha-1 antitrypsin

augmentation for safety outcomes ...................................................................... 37

Table 16 Primary outcomes and statistical analyses of the randomised and non-

randomised controlled trials ................................................................................ 39

Table 17 Studies assessing correlation between CT lung density and function

markers in AATD patients ..................................................................................... 41

the

Table 18 Secondary outcomes and statistical analyses of the direct randomised

trials ...................................................................................................................... 44

Table 19 Results of death due to adverse events across the included randomised

under Care.

controlled trials and single-arm studies ...............................................................

(CTH)

49

Table 20 Results of severe adverse events across the included randomised

controlled trials and single-arm studies ...............................................................

1982 Aged

50

released

Table 21 Results of treatment-related adverse events across the included

Act and

randomised controlled trials and single-arm studies ........................................... 52

been

Table 22 Results of dyspnoea across the randomised controlled trials and single-

arm studies ........................................................................................................... 53

has

Health

Table 23 Results of discontinuation due to a

of dverse events across the included

Information

randomised controlled trials and single-arm studies ........................................... 55

of

Table 24 Hospitalisation due to adverse events across the included studies .................... 56

Table 25 Results of any ad

document verse events across the included randomised controlled

trials and single-arm studies ................................................................................ 57

This

Department

Table 26 Results of sever

Freedom e adverse events across the RCTs and non-controlled

trials treatin

the g with Zemaira and PROLASTIN-C .................................................... 59

by

Table 27 Results of mortality across the randomised controlled trials at 24

months ................................................................................................................. 60

Table 28 Results of mortality across the non-randomised controlled trials ....................... 61

Table 29 Results of exacerbations across the direct randomised controlled trials ............ 62

Table 30 Results of exacerbations across the non-randomised trials ............................... 62

Table 31 Results of hospitalisations across the direct randomised controlled trials ......... 63

Table 32 Results of quality of life across the direct randomised controlled trials† ............ 63

Alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor augmentation – MSAC CA 1530

vi

Page 6 of 218

FOI 5155 - Document 4

Table 33 Results of quality of life across the non-randomised controlled trials† ............... 64

Table 34 Results of shuttle walk distance (metres) in the direct randomised

controlled trial ...................................................................................................... 65

Table 35 Results of change in FEV1 (% predicted or mL) across the direct

randomised controlled trials† ............................................................................... 66

Table 36 Results of change in FEV1 (% predicted or mL) across the non-

randomised controlled trials ................................................................................ 67

Table 37 Results of CT-measured lung density (total lung capacity, g/L per year)

across the direct randomised controlled trials .................................................... 68

the

Table 38 Results of carbon monoxide diffusing capacity across the direct

randomised controlled trials ................................................................................ 69

Table 39 Results of carbon monoxide diffusing capacity across the non-

under Care.

randomised controlled trials ................................................................................

(CTH)

69

Table 40 Results of lung infections in non-randomised control ed trials ........................... 70

1982 Aged

Table 41 Results of hospitalisation days in non-randomised controlled trials .................. 70

released

Table 42 Balance of clinical benefits and harms of A

Act 1PI relativ

and e to placebo as

measured by the critical patient-relevant outcomes in the key studies .............. 73

been

Table 43 Outline of Section C issues being addressed ........................................................ 74

has

Health

Table 44 Comparison of the RAPID trial’s patient population and the proposed

of

listing (Chapman et al. 2015) ................................................................................ 76

Information

Table 45 Comparison of Di

of rksen and EXACTLE patient population and the

proposed listing .................................................................................................... 77

document

Table 46 Comparison of the UK registry patient population and the proposed

listing .................................................................................................................... 78

This Freedom

Department

Table 47 Search strategy for AATD utility literature review ............................................... 79

the

Table 48 Results of AATD utility literature review .............................................................. 80

by

Table 49 Studies identified outlining utilities for AATD and COPD states .......................... 80

Table 50 EQ-5D values stratified by FEV1% predicted, obtained from the UK

ADAPT registry ...................................................................................................... 81

Table 51 Selected EQ-5D values stratified by GOLD (FEV1%) states from Moayeri

et al. 2016 ............................................................................................................. 83

Table 52 Selected utility values from COPD models outlined by Hoogendoorn et

al. 2017 ................................................................................................................. 85

Alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor augmentation – MSAC CA 1530

vii

Page 7 of 218

FOI 5155 - Document 4

Table 53 Utilities for lung transplantation .......................................................................... 87

Table 54 Summary of utility inputs for the Section D cost-effectiveness mode ................ 89

Table 55 Goodness of fit and parameters for FEV 1 >50 survival models .......................... 93

Table 56 Goodness of fit and parameters for FEV 1 <50 no decline survival models......... 94

Table 57 Goodness of fit and parameters for FEV1 <50 slow decline survival

models .................................................................................................................. 95

Table 58 Goodness of fit and parameters for FEV 1 <50 rapid decline survival

models .................................................................................................................. 96

Table 59 Summary of results of pre-model ing studies and their uses in the

the

economic evaluation ............................................................................................ 96

Table 60 Comparison between eligibility criteria in the RAPID study and

circumstances of use ............................................................................................

under

99

(CTH) Care.

Table 61 Baseline disease severity – RAPID population; baseline disease severity

in the model ....................................................................................................... 100

1982 Aged

Table 62 Summary of the economic evaluation ............................................................... 101

released

Act and

Table 63 Search terms used .............................................................................................. 102

Table 64 Summary of the process used t

been o identify and select studies for the

economic evaluation .......................................................................................... 103

has

Health

Table 65 Economic models assessing A1PI deficiency treatment .................................... 103

Information

of

Table 66 Summary of COPD economic model progression and mortality

of

characteristics .................................................................................................... 109

Table 67 Summary of the process used to identify and select lung transplant

document

studies for the economic evaluation .................................................................. 110

Department

Table 68

This Economic evaluations of lung transplantation ................................................... 111

Freedom

the

Table 69 Economic model health states ........................................................................... 119

by

Table 70 Baseline patient and disease characteristics of the modelled patient

cohort ................................................................................................................. 120

Table 71 Health state transition probabilities – Years 1-4 ................................................ 121

Table 72 Health state transition probabilities – Years >4 years ....................................... 121

Table 73 Health state dispositions at month 24 and month 30 and associated

transition probabilities – patients with severe depression at baseline ............. 122

Alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor augmentation – MSAC CA 1530

viii

Page 8 of 218

FOI 5155 - Document 4

Table 74 Resources associated with AT and disease management costs by COPD

severity ............................................................................................................... 124

Table 75 Utility value used in the model .......................................................................... 126

Table 76 Health care costs by resource type for base-case analysis (1,000-person

cohort) ................................................................................................................ 126

Table 77 Average patient health outcomes by health state and by outcome

measure for trial analysis ................................................................................... 127

Table 78 Health outcomes by health state and by outcome measure for lifetime

analysis (Per patient) .......................................................................................... 128

the

Table 79 Incremental Cost Effectiveness Ratio (1,000-patient cohort) ............................ 128

Table 80 Sensitivity analysis for lifetime analysis ............................................................. 132

Table 81 Key drivers of the economic model ....................................................................

under

134

(CTH) Care.

Table 82 Summary of the key assumptions used in the financial impact

assessment ......................................................................................................... 136

1982 Aged

Table 83 Population eligible for augmentation therapy with A1PI in Australia ............... 138

released

Act and

Table 84 Uptake of augmentation therapy with A1PI in Australia ................................... 140

Table 85 Estimated AT vial usage in Australia,

been 2019-2023 ............................................... 141

Table 86 Estimated financial impact to the National Blood Authority; total

has

Health

augmentation therapy market ........................................................................... 141

Information

of

Table 87 Estimated financial impact to MBS from augmentation therapy listing ............ 142

of

Table 88 Estimated financial impact to government from augmentation therapy

listing .................................................................................................................. 142

document

Table 89 Net government cost sensitivity analysis ........................................................... 143

This

Department

Table 90 Studies evaluat

Freedom ing different doses of A1PI therapies ........................................ 145

the

Table 91 PubMed Search Strategy .................................................................................... 149

by

Table 92 Embase Search Strategy ..................................................................................... 150

Table 93 Cochrane Search Strategy .................................................................................. 150

Table 94 Clinicaltrials.gov Search Strategy ....................................................................... 150

Table 95 Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials Search Strategy ........................ 151

Table 96 EU Clinical Trials Registry Search Strategy ......................................................... 151

Table 97 WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Strategy ................ 151

Alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor augmentation – MSAC CA 1530

ix

Page 9 of 218

FOI 5155 - Document 4

Table 98 Current Controlled Trials MetaRegister Search Strategy ................................... 151

Table 99 Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry Search Strategy ....................... 152

Table 100 CEA Registry Search Strategy ............................................................................. 152

Table 101 Characteristics of randomised controlled trials included in the systematic

review to assess efficacy .................................................................................... 153

Table 102 Characteristics of RCT studies used in the systematic literature review to

assess safety ....................................................................................................... 156

Table 103 Characteristics of non-randomised controlled trials used in the systematic

literature review to assess efficacy .................................................................... 159

the

Table 104 Characteristics of single arm studies used in the systematic literature

review to assess safety ....................................................................................... 165

Table 105 Evidence profile table of effectivness outcomes for A1PI c

under ompared to

(CTH) Care.

placebo for patients with severe AATD and emphysema .................................. 170

Table 106 Evidence profile table of safety outcomes for A1PI compared to placebo

1982 Aged

for patients with severe AATD and emphysema ................................................ 174

released

Table 107 Modified quality appraisal of included c

Act ase serie

and s investigations

according to the IHE Quality Appraisal of Case Series Studies (Guo et al.

been

2016)................................................................................................................... 177

Health

Table 108 Risk of bias in non–ran

has domised studies comparing A1PI augmentation

therapy and best supportive care or

of placebo .................................................... 178

Information

Table 109 Safety outcomes reported in RCT studies .......................................................... 179

of

Table 110 Safety outcomes reported in single arm studies ............................................... 183

document

Department

BOXES This Freedom

the

Box 1

Criteria for identifying and selecting studies to determine the safety of

by

purified human A1PI for the treatment of A1PI deficiency, leading to

COPD ..................................................................................................................... 20

Box 2

Criteria for identifying and selecting studies to determine the

effectiveness of purified human A1PI for the treatment of A1PI

deficiency, leading to COPD ................................................................................. 21

Alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor augmentation – MSAC CA 1530

x

Page 10 of 218

FOI 5155 - Document 4

FIGURES

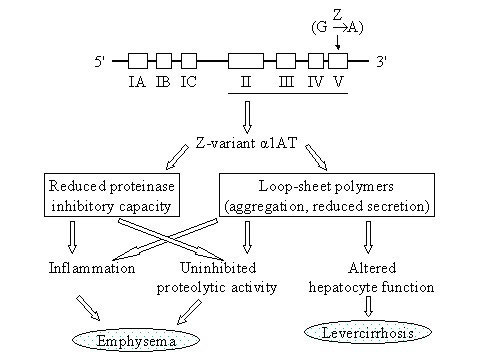

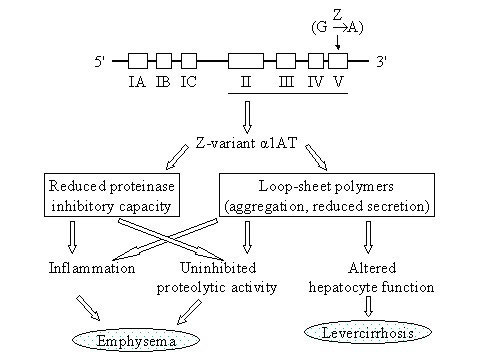

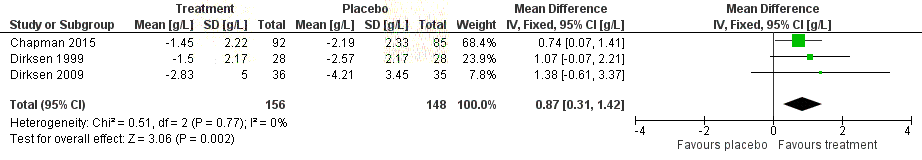

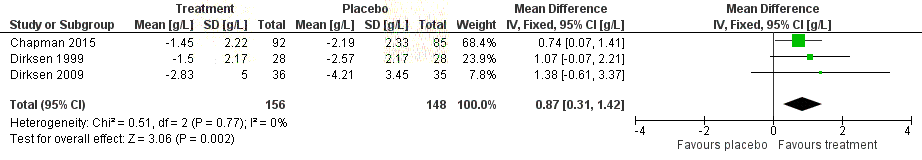

Figure 1

Simplified schematic of the pathway to lung and liver disease associated

with A1P1 deficiency (Fregonese and Stolk 2008) ............................................... 14

Figure 2

Current clinical management algorithm for patients with emphysema

and FEV1 <80% ..................................................................................................... 18

Figure 3

Proposed clinical management algorithm for patients with emphysema

and FEV1 <80% ..................................................................................................... 19

Figure 4

Summary of the process used to identify and select studies for the

assessment ........................................................................................................... 24

the

Figure 5

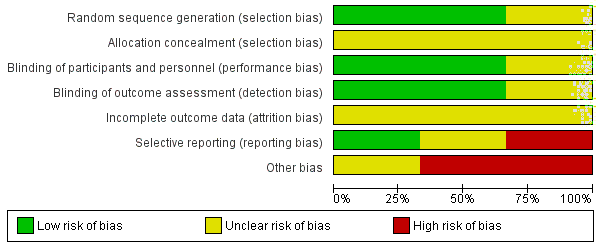

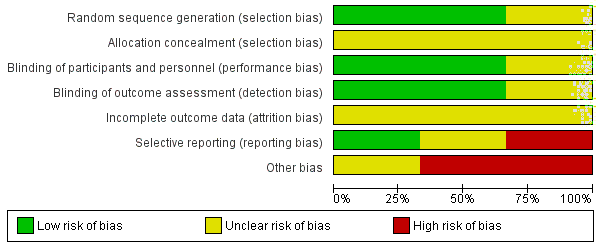

Summary of the overall risk of bias across the included studies ......................... 29

Figure 6

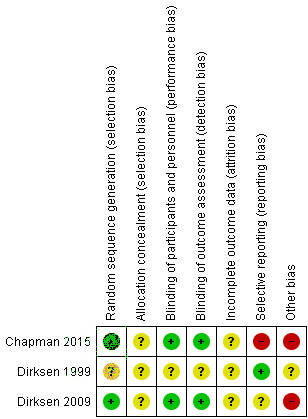

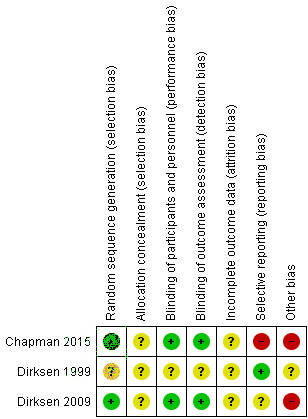

Risk of bias in the included randomised controlled trials .................................... 30

under Care.

Figure 7

Summary of risk of bias across the included non-randomised studie

(CTH) s ............... 34

Figure 8

Summary of risk of bias across the included single-arm studies ......................... 36

1982 Aged

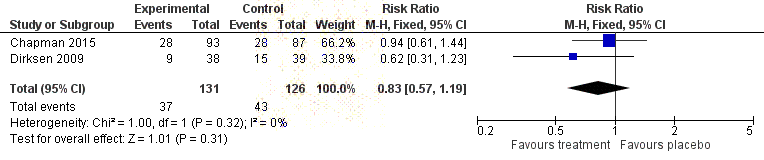

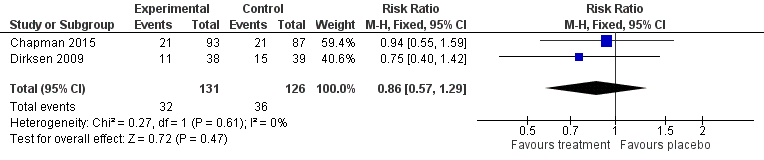

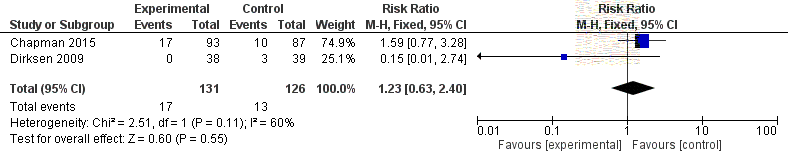

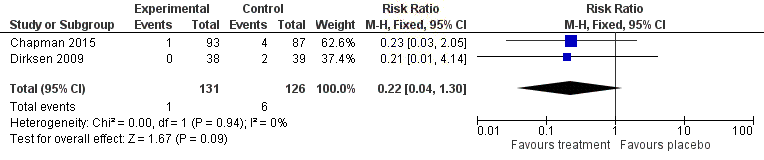

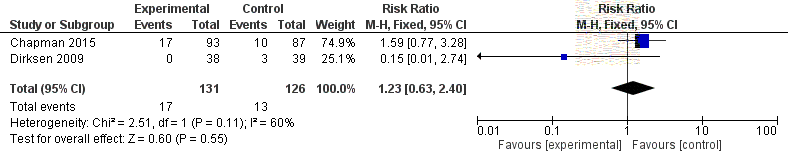

Figure 9

Forest plot indicating the pooled rate of severe adverse events for A1PI

released

compared to placebo ........................................................................................... 51

Act and

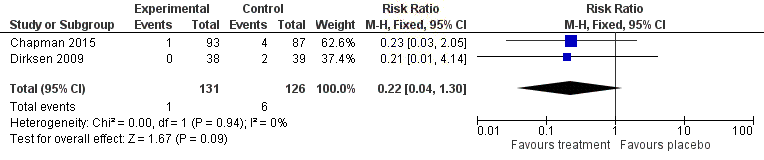

Figure 10 Forest plot indicating rate of death due to adverse events in A1PI

been

patients compared to placebo ............................................................................. 53

Figure 11 Forest plot indicating discontinuation due to

Health adverse events for A1PI

has

compared to placebo ...........................................................................................

of

55

Information

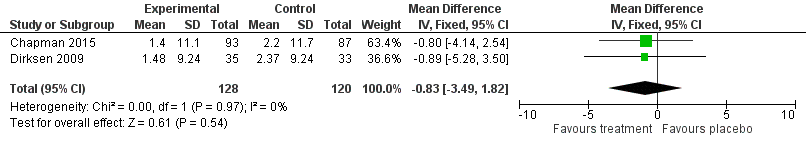

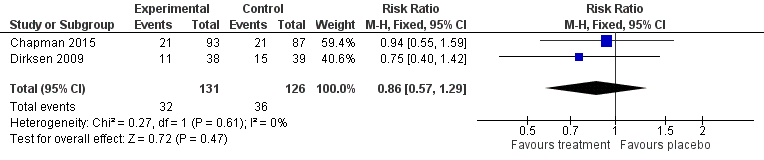

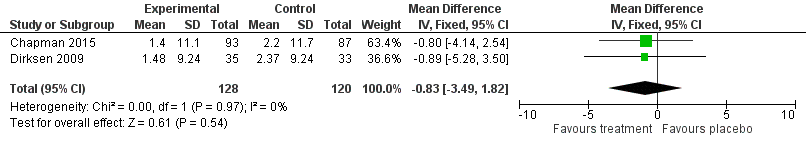

Figure 12 Forest plot indicating mean changes in St George’s Respiratory

of

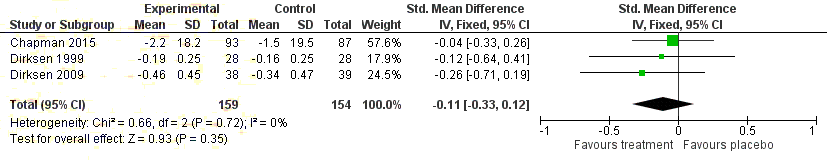

Questionnaire results for A1PI compared to placebo .......................................... 64

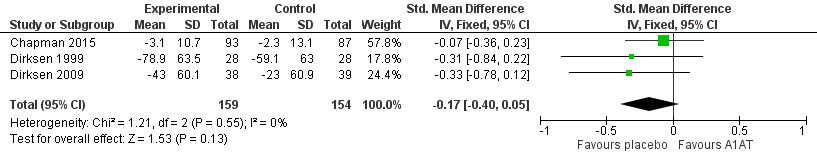

Figure 13 Forest plot indic

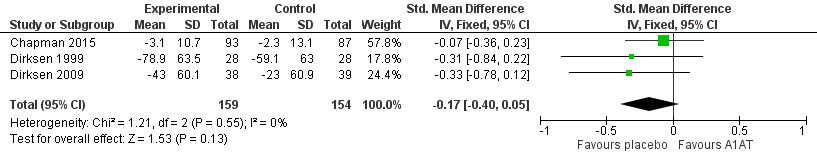

document ating standardised mean differnces in FEV1 for A1PI

compared to placebo ........................................................................................... 66

This

Department

Figure 14 Forest plot ind

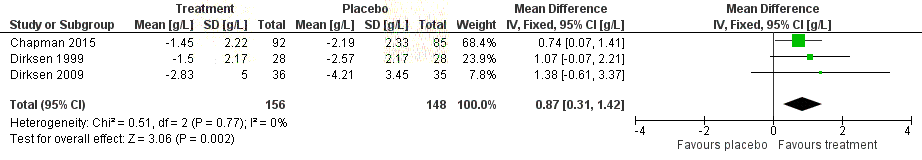

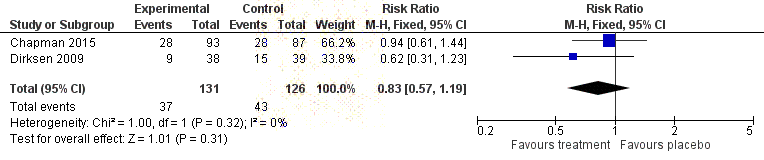

Freedom icating changes in CT-measured lung density (g/mL) in

A1PI comp

the ared to placebo measured at 24 to 30 months follow-up.

(Chapman 2015 and Dirksen 1999 reported an annualised rate, whereas

by

Dirksen 2009 reported the change from baseline at 24 months.) ....................... 68

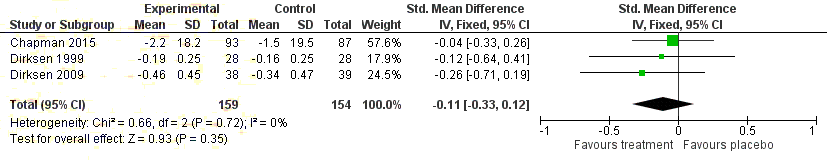

Figure 15 Forest plot indicating the standardised mean difference in carbon

monoxide diffusing capacity (DLCO) for A1PI compared to placebo ..................... 69

Figure 16 FEV1>50 survival models ...................................................................................... 92

Figure 17 FEV1 <50 no decline survival models ................................................................... 93

Figure 18 FEV1 <50 slow decline survival models ................................................................. 94

Figure 19 FEV1<50 rapid decline survival models ................................................................. 95

Alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor augmentation – MSAC CA 1530

xi

Page 11 of 218

FOI 5155 - Document 4

Figure 20 Decision tree for Augmentation Therapy ........................................................... 115

Figure 21 AT patient distribution between health states – based on RAPID data

and parametric modelling .................................................................................. 123

Figure 22 BSC patient distribution between health states – based on RAPID data

and parametric modelling .................................................................................. 123

Figure 23 Difference between AT and BSC patient distributions across health

states by year ..................................................................................................... 124

the

under

(CTH) Care.

Aged

released 1982

Act and

been

has

Health

Information

of

of

document

This Freedom

Department

the

by

Alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor augmentation – MSAC CA 1530

xii

Page 12 of 218

FOI 5155 - Document 4

LIST OF TERMS

Acronym/Abbreviation

Definition

A1PI

Alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor

AATD

Alpha-1 anti-trypsin deficiency

AT

Augmentation therapy

ARTG

Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods the

BOS

Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome

BODE

BMI, obstruction, dyspnoea, exercise cap

under acity

(CTH) Care.

BSC

Best supportive care

1982 Aged

COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

released

Act

CT

Computed tomography

and

been

DLCO

Diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide

Health

EQ-5D

Euro

has qol group 5 domain questionnaire

Information

of

FEV1

Forced expiratory volume in 1 second

of

FRC

Functional residual capacity

document

FVC

Forced vital capacity

This

Department

GOLD

Freedom Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease

the

ICER

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

by

IgA

Immunoglobulin A

IPD

Individual patient data

KCO

Diffusing coefficient for carbon monoxide

MBS

Medicare benefits schedule

MCIDs

Minimal clinically important differences

Alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor augmentation – MSAC CA 1530

xiii

Page 13 of 218

FOI 5155 - Document 4

MITT

Modified intention-to-treat

MSAC

Medical Services Advisory Committee

NBA

National Blood Authority

NPL

National Product List

PASC

PICO Advisory Sub-committee

PBAC

Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee

PD15

15th Percentile lung density

the

PI

Product information

under

PICO

Population, intervention, comparator, outcomes

(CTH) Care.

QALY

Quality-adjusted life year 1982 Aged

QoL

Quality of life released

Act and

RCT

Randomised control ed trials

been

SGRQ

St Georges Respiratory Questionnaire

has

Health

SMD

Standardised mean difference

Information

of

TGA

Therapeutic Goods Administration

of

TLC

Total lung capacity

document

This Freedom

Department

the

by

Alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor augmentation – MSAC CA 1530

xiv

Page 14 of 218

FOI 5155 - Document 4

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Main issues for MSAC consideration

• Minimum clinically important differences (MCIDs) for the primary outcome in the core

randomised controlled trials (RCTs), i.e. Computed tomography (CT)-measured lung density,

are not established in the literature. The best available evidence suggests a correlation

between CT-lung density decline and mortality and functional outcomes, however, it is

currently unclear whether, or to what extent, this translates to a clinically important impact

of augmentation therapy (AT) with Alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor (A1PI). No significant

differences were observed between A1PI and placebo for the remaining effectiveness

the

outcomes.

• Only a limited number of economic studies relating to AT cost effectiveness were identified

under

in the literature. Two American studies related resource use to expected life gain usin

Care.g USA

(CTH)

registry data. High incremental expected survival of 7+ years in non-smokers resulted in AT

appearing relatively cost effective. The RAPID trial was not powered to determine

1982 Aged

differences in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) or mortality, so uncertainty

released

surrounds the magnitude of this clinical benefit given available trial data.

Act and

• The model ing in this assessment generated a lifetime incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

been

(ICER) of s47(1)(b) per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) and a trial period ICER of s47(1)(b) .

It is evident that most benefits accrue after the RAPID trial period. The assumption about the

has

Health

price paid for the AT product is the key driver of model results. The base cost of AT assumes

of

a price per 1,000 ml of s47(1)

s47(1)

s47(1)

Information

(b)

. This varies from (b)

to (b)

per 1,000ml vial. The estimated

ICER varies considerably from s47(1)(b) to s47(1)(b) per QALY.

of

• The estimated NBA financial cost of AT listing is presented over a six-year costing proposal

document

period and is based on a s47(1)

s47(1)

(b)

uptake rate for AT by 2023. Uptake begins at (b) and

increases by s47(1)

Department

(b)

per year. The cost to the national blood authority (NBA) for the total AT

This

market is estimated to be

Freedom s47(1)(b) in 2019, increasing to s47(1)(b) in 2023.

the

• A key uncertainty is the price of AT. Given the large contribution of the AT product itself to

by

overall resource in the economic model, variations in price have a large impact on both

financial and economic attractiveness.

This contracted assessment examines the evidence supporting the listing of purified human A1PI on

the National Product List (NPL) for blood products. The service would primarily be used in the

outpatient hospital or clinic setting for the treatment of A1PI deficiency, also known as alpha-1

antitrypsin deficiency (AATD). Some patients may be able to self-administer the intervention at

home. The target population is people with severe A1PI deficiency (defined as serum A1 ≤11 μM)

Alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor augmentation – MSAC CA 1530

1

Page 15 of 218

FOI 5155 - Document 4

plus emphysema. The applicant claims that successful listing of the technology in the target

population and setting will lead to slower disease progression compared to best supportive care.

ALIGNMENT WITH AGREED PICO CONFIRMATION

This contracted assessment largely conforms to the PICO elements that were pre-specified in the

PICO Confirmation ratified by the PICO Advisory Sub-Committee (PASC). Only placebo-control ed

trials were identified for the evaluation of effectiveness outcomes (i.e. not best supportive care), and

eligible indications were broadened slightly for the evaluation of safety outcomes (i.e. not limited to

phenotype PiZZ).

PROPOSED MEDICAL SERVICE

the

The proposed medical service is for lifelong intravenous blood augmentation via weekly infusions of

purified human A1PI. The currently recommended dosing strategy is 60mg/kg p

under er week, noting that

(CTH) Care.

ongoing trials are investigating optimal dosing regimens. Augmentation therapy with A1PI is not

currently funded or reimbursed in private or public settings in Australia for this or any other clinical

indication.

Aged

released 1982

PROPOSAL FOR PUBLIC FUNDING

Act and

been

AT with A1PI is proposed for reimbursement on the National Products List (NPL), managed by the

National Blood Authority (NBA). As such, no Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) item descriptor is

has

Health

required.

Information

of

POPULATION

of

The intended population includes ex- or never-smoking patients with emphysema and severe A1PI

document

deficiency (serum A1 ≤ 11 μM). The frequency of Australians with PiZZ allele, which indicates the

most severely affected patients with greatly increas

Department ed risk of emphysema, is estimated at 1 in 5,584.

This Freedom

Null allele is very rare and its occurrence cannot be estimated. Based on educated estimates, the

the

number of people meeting the criteria for treatment with A1PI in Australia in 2018 was s47(1)

(b)

Considering treatment is

by lifelong and not curative, the number of patients being treated is expected

to have a moderate cumulative increase over time.

COMPARATOR DETAILS

The comparator intervention for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is best

supportive care (BSC). Strategies for the management of stable COPD include non-pharmaceutical

strategies (pulmonary rehabilitation and physical activity), pharmacological strategies (inhaled

Alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor augmentation – MSAC CA 1530

2

Page 16 of 218

FOI 5155 - Document 4

medications, corticosteroids and antibiotics), and prevention of deterioration and end-stage

strategies.

CLINICAL MANAGEMENT ALGORITHM(S)

Patients with A1PI deficiency are currently managed with BSC, which aims to provide symptomatic

relief. AT is an additive intervention to supplement BSC for patients with emphysema. The current

(Figure 2) and proposed (Figure 3) clinical management algorithms are presented in the report.

CLINICAL CLAIM

The applicant claims that, relative to best supportive care, A1PI slows disease progression in patients

the

with severe A1PI deficiency and emphysema.

APPROACH TAKEN TO THE EVIDENCE ASSESSMENT

under

(CTH) Care.

A systematic review of published and unpublished literature was undertaken. The medical literature

was searched to identify relevant studies in Embase on 23 May 2018 and in PubMed and The

1982 Aged

Cochrane Library on 24 May 2018. RCTs were appraised for risk of bias using the Cochrane RoB 2.0

released

tool, non-randomised studies were appraised using the Cochra

Act ne ROBINS-I tool, and single-arm

and

studies were appraised using the IHE checklist for observational studies.

been

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE EVIDENCE BASE has

Health

Three RCTs were identified that evaluated the effectiv

of eness of A1PI compared to placebo in 313

Information

patients. Included patients were relatively homogenous across the included studies, representing ex-

of

or never-smokers with severe A1PI deficiency (serum A1 ≤11µM) and emphysema (FEV1 25% to

80%). The included RCT outcomes were generally well conducted; however, method of allocation

document

concealment was poorly reported across all trials. Seventeen single arm studies were identified that

provided evidence on the safety of A1PI.

This Freedom

Department

RESULTS

the

by

SAFETY

Seventeen single arm studies were included for the evaluation of safety outcomes. Key safety

outcomes were: death due to adverse events, severe adverse events, and discontinuation or

hospitalisation due to adverse events.

Six deaths occurred in the eligible studies, which included 899 patients. None of these deaths were

reported to be treatment-related. Severe adverse events were also uncommon, with a median

occurrence of 2% in the patient population (range 0%-38%). Discontinuation due to adverse events

had a median occurrence of 0.5% in the patient population (range 0%-12%) across nine studies.

Alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor augmentation – MSAC CA 1530

3

Page 17 of 218

FOI 5155 - Document 4

Hospitalisation had a median occurrence of 1.5% in the patient population (range 0%-14%) across

four studies.

Three studies reported safety in patients treated with one of the two therapies under assessment,

Zemaira and PROLASTIN-C. Al of these studies found that rates of severe adverse events were

unchanged across intervention groups.

Fifteen studies reported any adverse event, with a rate ranging from 0% to 100% and a median of

37%. Differences between the RCTs and observational studies in the rates of any adverse event may

indicate under-reporting in the observational studies. Dyspnoea and treatment-related adverse

events were also reported. Dyspnoea occurred after AT in 12.5% of the patient population (range

0%-35%). Events reported by the authors to be treatment-related had a median occurrence of 11%

the

in the patient population (range 0%-38%).

Overall, it appears that the intervention is safe, with most events being related to the underlying

under Care.

disease.

(CTH)

EFFECTIVENESS

1982 Aged

No direct trials comparing A1PI to BSC were identified. Three RCTs in

released vestigated the clinical efficacy

of A1PI compared to placebo. CT-measured lung density was the p

Act rimary o

and utcome in two RCTs, and

FEV1 was the primary outcome in one RCT. been

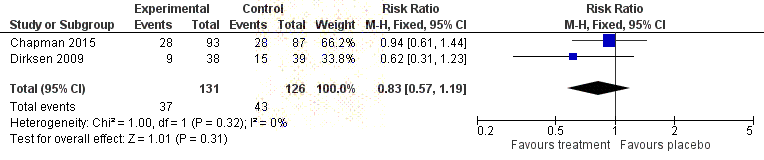

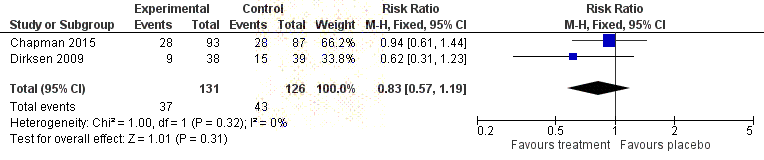

No significant differences between A1PI and placebo were identified in relation to mortality,

has

Health

exacerbation of COPD, hospitalisation due to COPD exacerbation, quality of life (SGRQ), respiratory

of

function (FEV1), exercise capacity (incremental shuttle walk test) or carbon monoxide diffusion

Information

capacity (DLCO). No relevant data was identified for dyspnoea.

of

The only statistically significant difference was observed for CT-measured lung density, which

document

favoured A1PI, however, the clinical significance of this difference is uncertain, as MCIDs for changes

in CT-lung density have not been established in the literature.

This Freedom

Department

The summary of findings (incor

the porating both benefits and harms) is shown in Table 1.

by

Alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor augmentation – MSAC CA 1530

4

Page 18 of 218

FOI 5155 - Document 4

Table 1

Balance of clinical benefits and harms of A1PI relative to placebo as measured by the critical patient-

relevant outcomes in the key studies

Outcomes

Risk with

Risk with A1PI

Relative effect

Participants

Quality of

Comments

(units)

placebo

(95% CI)

(95% CI)

(studies)

evidence

Follow-up

(GRADE)

Uncertain due

Mortality

12 per 1,000

RR 0.35

180

34 per 1,000

⨁⨁⨁⨀

to low event

F/U 24 months

(2 to 78)

(0.05 to 2.27)

(1 RCT)

MODERATE

rate, RR subject

to error

Quality of life

MD 0.83 points

Direction

(SGRQ)

lower

248

favours

-

-

⨁⨁⨀⨀

placebo; not

F/U 24 to 30

(3.49 points lower

(2 RCT)

LOW

statistical y

months

to 1.82 points

higher)

significant

Annual

Higher reported RR

Direction

the

exacerbation

(1.26, 95% CI 0.92