Final report for DVA Human Research Ethics Committee:

Study title: Switching medicines in the Veteran population (ref: E005/009)

Principal researcher:

s 47F

PhD student

c/o Quality Use of Medicines and Pharmacy Research Centre,

University of South Australia

GPO Box 2471, Adelaide SA 5001

Phone: s 47F

Email: s 47F

Outcome of completed research:

Since December 1994, a brand substitution policy has operated on the Pharmaceutical

Benefits Scheme (PBS) and Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (RPBS), the

nationally funded schemes for medicine subsidy in Australia. Patients can receive a brand

or generic product other than the one prescribed if products are bioequivalent and the

prescription is not marked “substitution not permitted”. Ideally patients should remain on

the same product following initial brand substitution; however there is no limit to the

number of brand substitutions. There are concerns that multiple product changes occur,

with the potential to confuse patients and compromise the quality use of medicines

(QUM). Increased use of generics in Australia is encouraged; however, the brand

substitution policy has not been evaluated since implementation.

This research evaluated implementation of the brand substitution policy from Australia’s

National Medicines Policy perspective, by studying the frequency of brand substitution for

government subsidised medicines and the extent of switching between products by

cohorts of individuals. Administrative claims data for government subsidised medicine

dispensings on the RPBS were used.

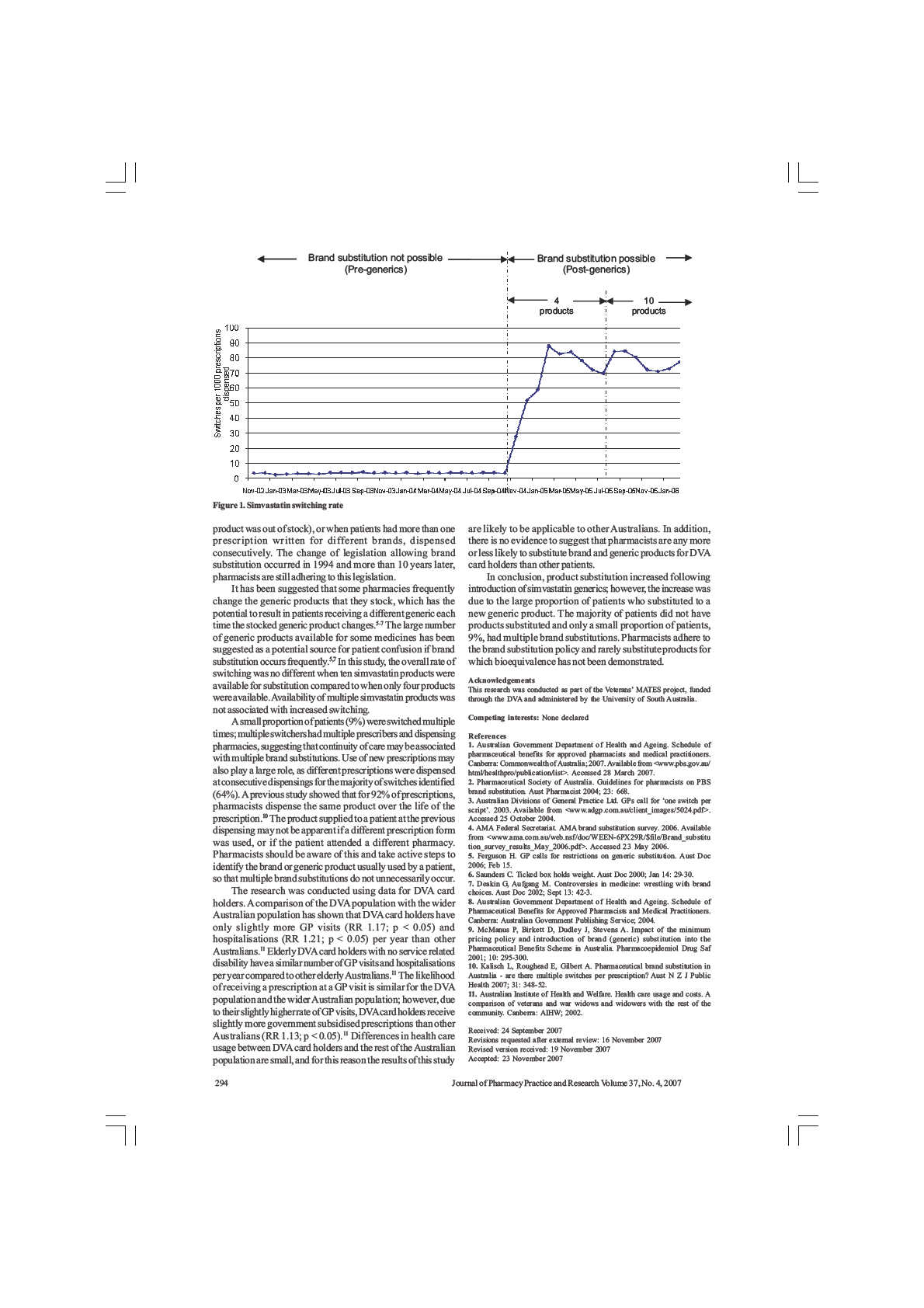

The first study in this research characterised brand substitution using the example of

simvastatin, a medicine for which brand substitution was first possible in 2004. Trends in

the rate of brand substitution and the extent of brand substitution per patient were

examined. Over 90% of patients in this analysis had two or less switches; only 9% had

multiple switches. Simvastatin patients with multiple switches were more likely to have

had more prescribers, dispensing pharmacies and original prescriptions than other

patients (p < 0.0001)

The second study of the research further characterised implementation of the brand

substitution policy using six medicine examples. Trends in the rate of brand substitution

for these medicines were examined and the number of brand substitutions per

prescription form and per patient identified. While switching occurred for all products,

analysis of individual prescriptions showed that 92% of prescription forms had the same

product supplied on each repeat dispensing. Analysis by patient showed over 80% of

patients either had no switches or only a single brand substitution, confirming the results

of the first study. Patients with multiple switches were more likely to receive a product with

a brand premium at their initial dispensing.

To complete the brand substitution picture, the final study of the research examined the

extent of brand substitution for all medicines used by a cohort of patients on multiple

medicines. Amongst this cohort, 83% of patients either had no switches or only a single

brand substitution during follow-up for all medicines received. Patients at risk of having

multiple brand substitutions had more prescription medicines, hospital admissions,

dispensing pharmacies, prescribers and longer fol ow-up than other patients (p < 0.0001).

Progress report for DVA HREC – “Switching medicines in the veteran population”

The overall conclusion from the findings of these studies is that the minimum pricing policy

and brand substitution are implemented in the manner intended. They facilitate consumer

access to cheaper medicines without resulting in multiple switches for over 80% of

patients. Initiatives to reduce multiple switching amongst patients identified as being at

increased risk of having multiple switches would further support implementation of the

brand substitution policy.

Conference presentations arising from this research:

A number of conference presentations have reported results of this research. Al

conference abstracts and presentations were reviewed and approved by DVA (Medication

Management Section) prior to presentation. References to the conference proceedings

are listed below, along with a copy of the presentation abstract:

Kalisch L, Roughead E, Gilbert A. Brand switching following patent expiry of simvastatin

and introduction of generic alternatives. In: s 47F E and s 47F C, editors. Proceedings of

the joint meeting of the Australasian Society of Clinical and Experimental

Pharmacologists and Toxicologists (ASCEPT) and the Australasian Pharmaceutical

Science Association (APSA); Melbourne; December 2005. [poster presentation]

Legislation to allow brand substitution by pharmacists at the point of dispensing

was introduced in 1994. Since then use of generic medicines has increased;

however the degree of switching between dif erent brands and generics is

unknown. It has been suggested that switching brands and generics can confuse

patients and lead to potential harm.

This study aimed to identify the rates of switching between dif erent brands and

generics of simvastatin from one dispensing to another.

Simvastatin was chosen as the study drug because a generic alternative became

available in November 2004 (prior to patent expiry in July 2005), allowing

comparison of drug use prior to and post availability of generics. Other statins do

not yet have bioequivalent brands available for substitution. Prescription claims

data for dispensing of simvastatin on the Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits

Scheme were analysed.

Preliminary results revealed that between November 1st 2003 and February 28th

2005 542,018 simvastatin prescriptions were dispensed to 110,049 persons. 57%

of patients were male. In the year prior to the availability of generic versions of

simvastatin (November 1st 2003 – October 31st 2004), simvastatin was dispensed

to 43,792 patients, of which 860 (2%) switched at least once. The rate of switching

was one switch per 237 simvastatin prescriptions dispensed. In the first four

months post generic simvastatin availability (three bioequivalent brands available),

38,953 patients were dispensed simvastatin, of which 3,196 (8.2%) switched

brands at least once, with a rate of one brand switch per 35 prescriptions

dispensed.

Future analysis of the data wil assess the influence of switching pharmacy on the

rate of brand switching, as wil the influence of switching prescriber. The influence

of patient characteristics such as age and gender on switching wil be determined.

Rates of switching after July 2005, when 10 simvastatin brands were available,

wil be compared with earlier switching rates.

Kalisch L, Roughead E, Gilbert A. Switching between brand name and generic medicines:

the example of simvastatin. In: Day R and s 47F R, editors. National Medicines

Symposium 2006. Quality Use of Medicines: Balancing beliefs, benefits and harms;

Canberra; June 2006. [oral presentation]

Since introduction of the brand substitution policy to the Pharmaceutical Benefits

Scheme (PBS) in 1994, use of generic medicines and the number of generics

available has increased. In 2005 when over 400 generics were available, 56% of

PBS prescriptions were dispensed at the patient co-payment price, compared to

2

Progress report for DVA HREC – “Switching medicines in the veteran population”

17% in 1994. There is potential for patient confusion and harm when brands and

generics are switched, particularly if switching is common. A small Australian study

found that 56% of patients do not understand the dif erence between brand and

generic names of medicines. Currently, the extent of switching between brand and

generic medicines is unknown. This study aimed to identify simvastatin switching

rates and associated factors.

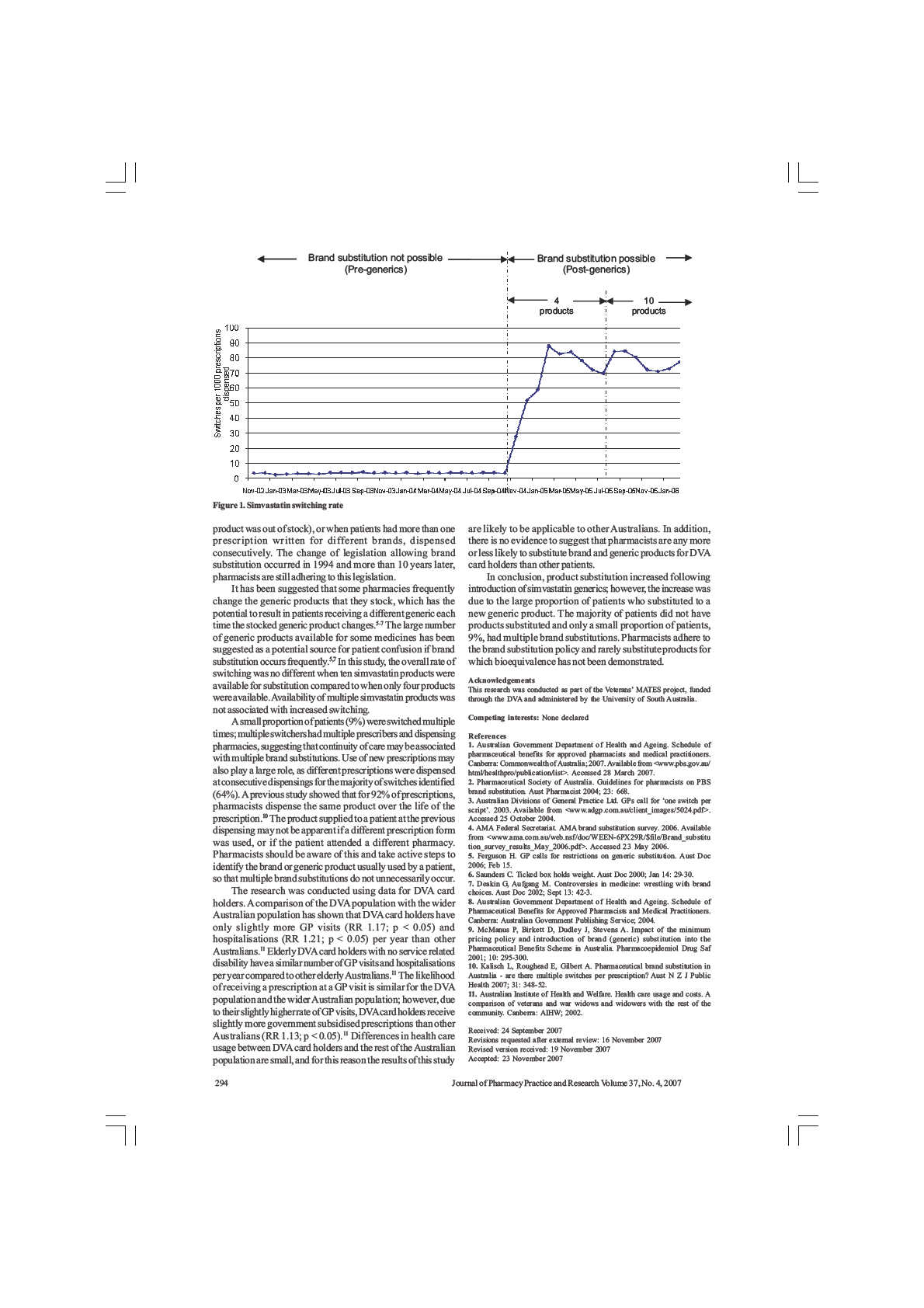

The first simvastatin generic was PBS listed in November 2004. Switching rates

were compared pre and post generic simvastatin availability. A switch was

identified if different brands or generics were dispensed consecutively. Analyses

were conducted using Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme prescription

claims data.

Prior to generic availability when two non-substitutable brands were available,

there was one switch per 279 prescriptions dispensed. This was most commonly

associated with the use of a dif erent prescription (87% of switches), rather than a

repeat of the same prescription. The switching rate on individual prescriptions was

one switch per 1,773 dispensings. Following introduction of the first generic the

overall switching rate increased to one switch per 14 dispensings. Of these

switches, 24% coincided with dispensing at a dif erent pharmacy to the previous

and 70% were associated with the use of a dif erent prescription. When individual

prescriptions were followed the switching rate was lower, with one switch per 38

dispensings. In 21% of these cases, the switch coincided with a change in

pharmacy at which the medicine was dispensed.

The introduction of a simvastatin generic appears to have increased switching.

Further work wil identify switching rates after August 2005 when ten simvastatin

brands and generics were available.

Kalisch L, Roughead E, Gilbert A. Switching between brand name and generic medicines

- are there multiple switches per prescription? In: s 47F A and s 47F R, editors. Annual

conference of the Australasian Pharmaceutical Science Association; Adelaide; December

2006. [oral presentation]

Introduction: Since December 1994, the brand substitution policy has operated

on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) and Repatriation PBS (RPBS).

Patients can receive a brand or generic product other than the one prescribed if

the products being substituted are bioequivalent and the prescriber hasn’t

specified that substitution cannot occur. Currently, there is no limit to the number

of brand substitutions on repeats of an individual prescription. Doctors have

expressed concern that patients may receive a different product each time their

prescription repeats are dispensed, which has the potential to confuse patients.

The Australian Divisions of General Practice has suggested that a limit of one

switch per prescription should be enforced. We aimed to identify the number of

switches per prescription for a range of medicines and to determine the number of

different products supplied on each prescription.

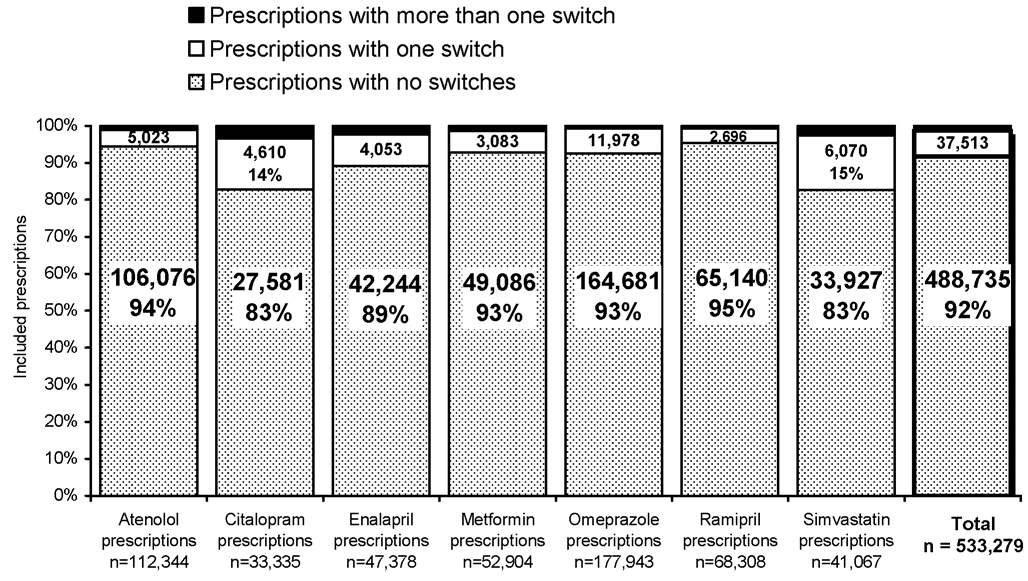

Methods: Al RPBS prescription claims between January 1st 2001 and February

28th 2006 were identified for enalapril, ramipril, atenolol, simvastatin, citalopram,

metformin and omeprazole. Original prescriptions with five repeats and all supplies

dispensed were included. Switches were identified if a dif erent brand or generic

product was supplied on consecutive repeat dispensings. The number of switches

and the number of different products supplied per prescription was calculated.

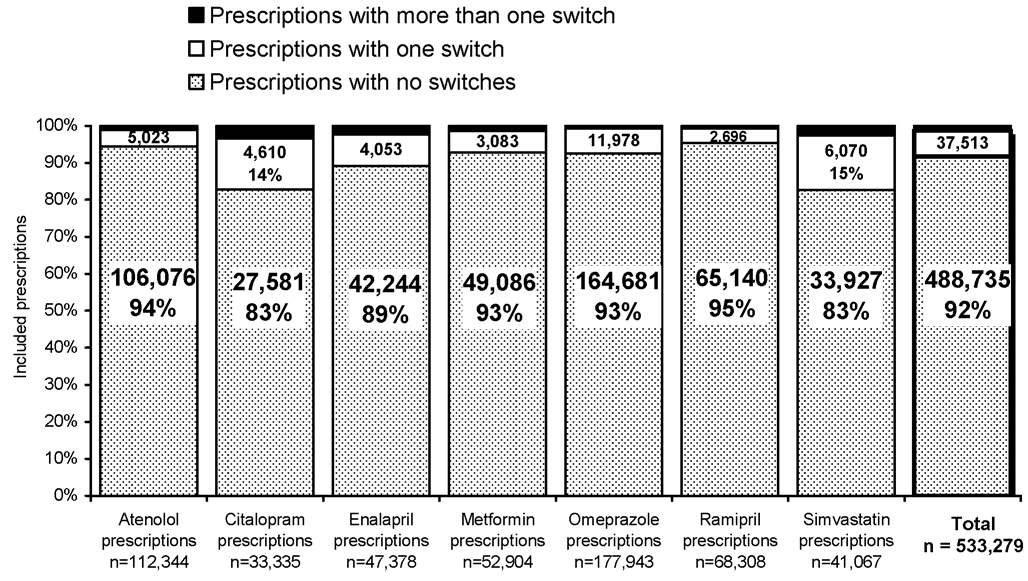

Results: 535,942 original prescriptions were included. 491,398 (92%) had no

switches on repeats and 37,513 (7%) had only one switch. Only 1% of all

prescriptions had more than one switch identified on repeats, and in most cases

only two dif erent products were supplied. Only seven of the 563,677 prescriptions

studied had a dif erent product supplied on each repeat.

Conclusion: Most prescriptions have the same product supplied on each repeat,

and if switches occur in most cases there is only one switch per prescription.

3

Progress report for DVA HREC – “Switching medicines in the veteran population”

Multiple switches per prescription are uncommon and multiple different products

are rarely supplied on repeats of the same prescription.

Kalisch L, Roughead E, Gilbert A. Brand substitution or multiple switches per patient? An

analysis of pharmaceutical brand substitution in Australia. In: Abstracts of the 23rd

International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology and Therapeutic Risk Management;

Quebec City, Canada; August 2007. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 2007;

16(S2): S55-S56. [oral presentation]

Background: In Australia, when prescriptions are dispensed, brand substitution

can occur if products are bioequivalent and the prescription is not marked

“substitution not permit ed”. Ideally patients should remain on the same product

following the initial brand substitution; however there are concerns that multiple

switches occur. Generics are sold under trade names rather than the generic drug

name and product appearance may differ. Multiple substitutions may cause

confusion due to the change in product name and appearance. The generics

market is growing; however the extent of multiple switching is unknown.

Objectives: To identify whether brand substitution or multiple switching occurs.

Methods: Department of Veterans’ Affairs pharmacy claims data for atenolol,

citalopram, enalapril, metformin, omeprazole and ramipril were analysed. Claims

were included for patients with ≥4 supplies of the same medicine each year from

2001 to 2005. Switches were identified if dif erent products were dispensed

consecutively within 60 days. Brand substitution was defined as one switch, or no

more than 2 switches more than a year apart over the 5 year period. Multiple

switching was defined as use of ≥3 products in 365 days, use of 2 products and ≥4

switches in 365 days, >10 switches over 5 years, and/or use of ≥5 products over 5

years.

Results: 36,538 episodes of medicine dispensings were identified, representing

33,892 patients. 14,779 patients (44%) had no switches and 9,321 (28%) met

brand substitution criteria for each medicine used. 6,168 patients (18%) had

multiple switches for at least one medicine, and over the 5 years 2,722 had more

than one multiple switching episode. Multiple switches were most commonly

identified as use of ≥3 products in 365 days (3,799 patients, 62% of multiple

switchers) or use of 2 products and ≥4 switches in 365 days (2,295 patients, 37%

of multiple switchers).

Conclusions: Most patients using medicine over 5 years (71%) either did not

switch, or demonstrated brand substitution. 18% of patients had multiple switches.

Future research should identify the people, places and specific medicines in which

multiple switching is likely to occur, so that it can be avoided in patients at risk of

confusion and adverse outcomes.

Kalisch L, Roughead E, Gilbert.

Pharmaceutical brand substitution in Australia: identifying

risk factors associated with having multiple brand substitutions. In: s 47F J and s 47F R,

editors. National Medicines Symposium 2008. QUM: what does it really mean for you?

The science, the policy and the practice; Canberra; May 2008. [oral presentation]

Background: The brand substitution policy has operated on the PBS since

December 1994. Anecdotal reports have highlighted the potential for confusion if

brand substitution occurs multiple times, particularly for the elderly and people

using multiple medicines. Factors associated with having brand and generic

products substituted multiple times are unknown.

Aims: To identify factors associated with having multiple brand substitutions and

to determine the frequency with which people have multiple brand substitutions for

multiple medicines.

Methods: A retrospective cohort study was conducted using Department of

Veterans’ Affairs administrative claims data from June 1st 2005 to August 31st

2006. The analysis was limited to people with the opportunity for brand substitution

4

Progress report for DVA HREC – “Switching medicines in the veteran population”

of two or more medicines. “Switches” were identified for each medicine if different

brand or generic products were supplied at consecutive dispensings. The total

number of switches for each medicine dispensed to a patient was determined.

Multivariate analysis was conducted to identify factors associated with multiple

switches.

Results: 84,040 people were included. On average, they received 11 prescription

medicines. 49% of people received the same product throughout follow-up for

each medicine and 34% had a single brand substitution. 17% had multiple

switches for one or more medicine; however, only 3% of all patients had multiple

switches for more than one medicine. Independent risk factors associated with

having multiple switches were increasing number of hospital admissions,

prescription medicines, co-morbidities, prescribers and dispensing pharmacies;

and living in an aged-care facility or major city.

Conclusions: Most patients do not have multiple brand substitutions of their

medicine, even when all medicine use is considered. This is the first study to

identify risk factors associated with having multiple brand substitutions. Quality use

of medicines interventions targeting individuals with these risk factors could

minimise the potential for patient confusion as a result of multiple brand changes.

Publications arising from this research:

Work from this research has been presented in the following peer reviewed publications:

Kalisch LM, Roughead EE, Gilbert AL. Do pharmacists adhere to brand substitution

guidelines? The example of simvastatin. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research

2007; 37(4): 292-294.

Kalisch LM, Roughead EE, Gilbert AL. Pharmaceutical brand substitution in Australia –

are there multiple switches per prescription? Australian and New Zealand Journal of

Public Health 2007; 31(4): 348 – 52.

Kalisch LM, Roughead EE, Gilbert AL. Brand substitution or multiple switches per patient?

An analysis of pharmaceutical brand substitution in Australia. Pharmacoepidemiology and

Drug Safety 2008; 17(6): 620 – 25.

This research also formed the basis for a PhD thesis authored by the s 47F

s 47F

).

Copies of these peer reviewed publications and the PhD thesis are appended for

reference.

Events of significance (e.g. adverse outcomes) that have occurred during

the study:

No adverse events of significance have occurred during the study.

Maintenance and security of records:

Security of records has been maintained at all times during the progress of this study. The

study was conducted as part of the Veterans’ MATES project. Well defined security

guidelines exist for the Veterans’ MATES project and regular security audits are

conducted. As outlined in the Veterans’ MATES project management plan, all personal

information has been stored and analysed at the “Protected” security level, as defined in

the Protective Security Manual and DVA security manual. Re-coded, de-identified data

were used for the study. The re-coded data were not removed from the secure area of

QUMPRC.

5

Progress report for DVA HREC – “Switching medicines in the veteran population”

Compliance with the approved proposal and protocol:

An amendment to the original research proposal was submitted to DVA HREC for

consideration at its April 2006 meeting and was endorsed by DVA HREC. No changes

have been made to the research protocol since this amendment was endorsed by DVA

HREC. The research was conducted in accordance with the approved research proposal

and protocol.

Compliance with any conditions of approval:

No special conditions of approval were set for this research.

6

Pharmaceutical brand substitution

in Australia

Lisa Marie Kalisch

BPharm (Hons)

A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

Sansom Institute

School of Pharmacy and Medical Sciences

Division of Health Sciences

University of South Australia

March 2008

Table of contents

List of figures.......................................................................................................................vi

List of tables .......................................................................................................................vii

Abbreviations used throughout the text ...........................................................................ix

Summary..............................................................................................................................xi

Statement of originality ....................................................................................................xiii

Acknowledgement .............................................................................................................xiv

Communications arising from this thesis ........................................................................ xv

Chapter 1: Introduction ...................................................................................................... 1

Chapter 2: Australia’s National Medicines Policy - the medicines framework in

Australia ............................................................................................................................... 4

2.1 Australia’s National Medicines Policy ......................................................................... 4

2.1.2 Quality, safety and efficacy of medicines ................................................................. 7

2.1.4 A responsible and viable medicines industry in Australia ...................................... 11

2.2 Challenges for the supply and subsidy of medicines locally and internationally... 13

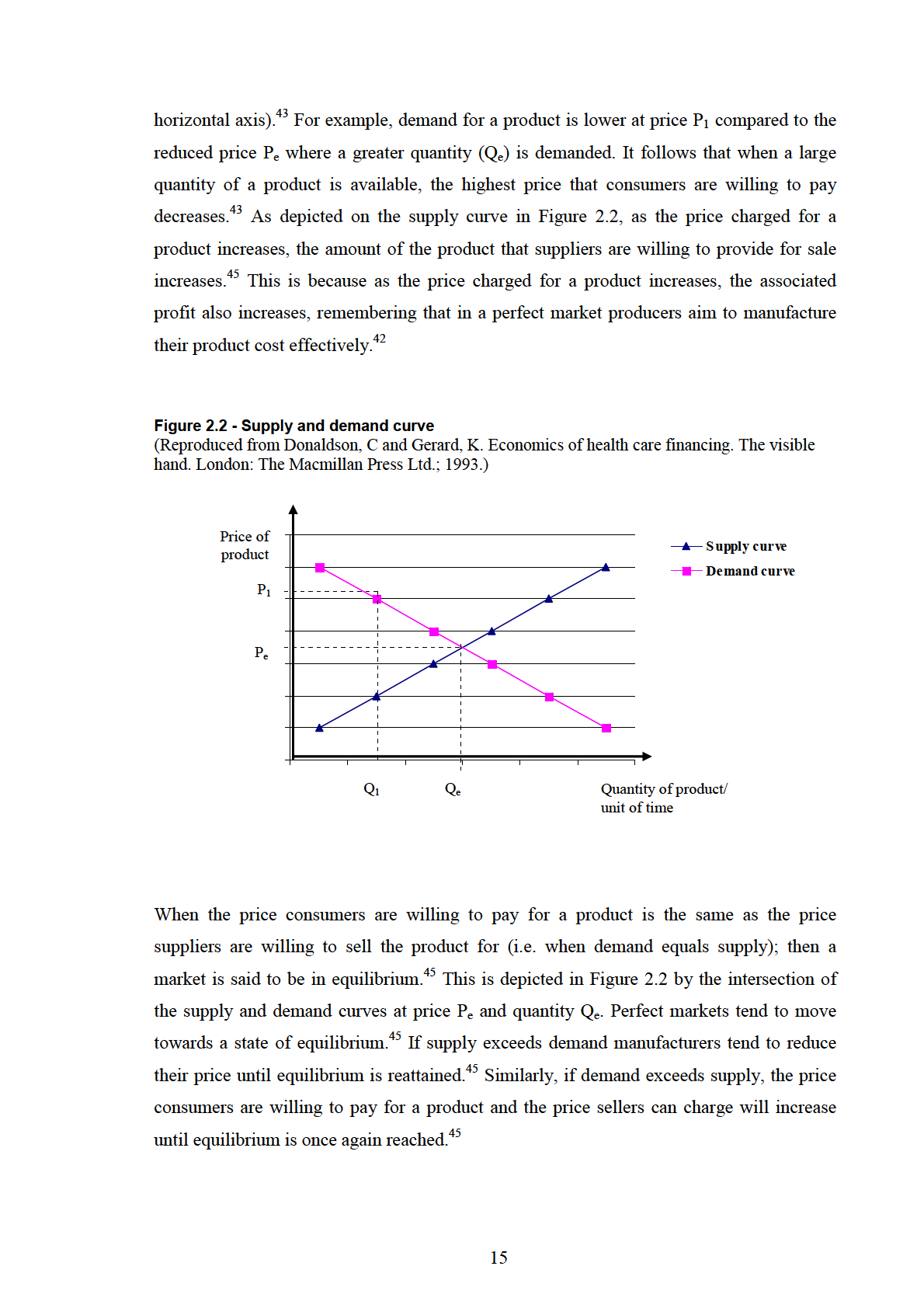

2.2.1 Supply and demand economic theory – an overview.............................................. 13

2.2.2 Pharmaceutical policies to influence demand ......................................................... 16

2.2.2(i) Prescription cost-sharing ................................................................................. 17

2.2.2(ii) Formularies ..................................................................................................... 17

2.2.2(iii) Generic substitution policies ......................................................................... 18

2.2.2(iv) Prescribing feedback, education and guidelines ............................................ 18

2.2.2(v) Prescribing budget restrictions........................................................................ 19

i

2.2.3 Pharmaceutical policies to influence supply ........................................................... 19

2.2.3(i) Medicines licensing and regulatory approval .................................................. 19

2.2.3(ii) Reference pricing policies .............................................................................. 19

2.2.3(iii) Cost effectiveness pricing policies and economic evaluation ....................... 20

2.3 Policies influencing supply and demand, implemented to ensure continued access

to medicines in Australia via the PBS and RPBS ........................................................... 20

2.3.1 Pricing and listing of PBS medicines...................................................................... 22

2.3.2 Patient co-payments ................................................................................................ 22

2.3.2(i) Safety Net provisions....................................................................................... 23

2.3.3 The minimum pricing policy................................................................................... 24

2.3.3(i) Brand substitution by pharmacists................................................................... 24

2.3.3(ii) Bioequivalence of brand and generic products............................................... 25

2.3.4 The therapeutic group premium policy ................................................................... 26

2.4 Co-payments, the minimum pricing policy and therapeutic group premium

policy: influencing supply and demand on the PBS and RPBS..................................... 27

Chapter 3: PBS policies to influence supply and demand: what is the impact on

achieving the National Medicines Policy objectives?...................................................... 28

3.1 Review of the literature on PBS patient co-payments .............................................. 28

3.1.1 International studies of the effects of increasing patient co-payments ................... 33

3.1.2 Patient co-payments - some conclusions................................................................. 35

3.2 Review of the literature on the PBS minimum pricing policy and brand

substitution policy .............................................................................................................. 36

3.2.1 International studies of brand substitution .............................................................. 47

3.2.2 Brand substitution policies - some conclusions ...................................................... 56

3.3 Review of the literature on the PBS therapeutic group premium policy ............... 57

3.3.1 International studies of reference pricing policies .................................................. 61

3.3.2 Therapeutic group premium and reference pricing policies – some conclusions ... 63

3.4 PBS policies to influence supply and demand – overall conclusions....................... 63

3.4.1 Gaps in the evidence base: the minimum pricing and brand substitution policies

and their potential influence on QUM ............................................................................. 64

Chapter 4: Research design .............................................................................................. 67

4.1 Introduction.................................................................................................................. 67

4.2 Research aims............................................................................................................... 67

ii

4.3 Study design.................................................................................................................. 68

4.4 Study population and data source.............................................................................. 70

4.4.1 DVA treatment cards and level of entitlement to DVA subsidised health services 70

4.4.2 Characteristics of DVA treatment card holders ...................................................... 70

4.4.3 DVA administrative claims data ............................................................................. 71

4.4.3(i) Pharmacy data.................................................................................................. 72

4.4.3(ii) Private hospital admissions data..................................................................... 72

4.4.3(iii) Medical and allied health data ....................................................................... 72

4.4.4 Appropriateness and relevance of DVA administrative claims data for use in the

present research ................................................................................................................ 73

4.5 Preview of studies included in this thesis................................................................... 73

4.6 Ethical approval........................................................................................................... 74

Chapter 5: Brand substitution of government subsidised medicines in Australia: the

example of simvastatin ...................................................................................................... 75

5.1 Introduction.................................................................................................................. 75

5.2 Aims............................................................................................................................... 77

5.3 Methods......................................................................................................................... 77

5.3.1 Identification of switches ........................................................................................ 77

5.3.2 Statistical analysis ................................................................................................... 79

5.4 Results ........................................................................................................................... 80

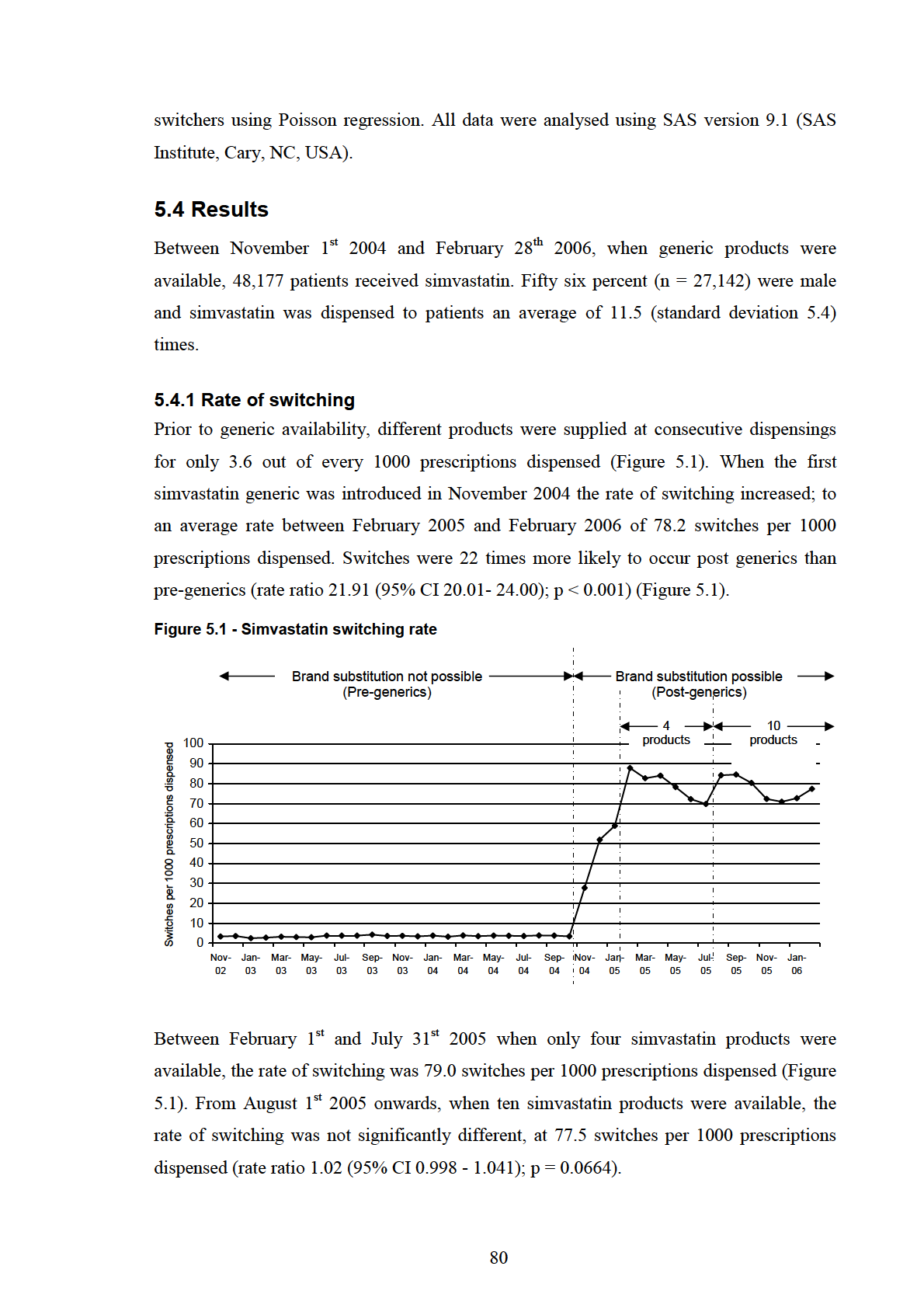

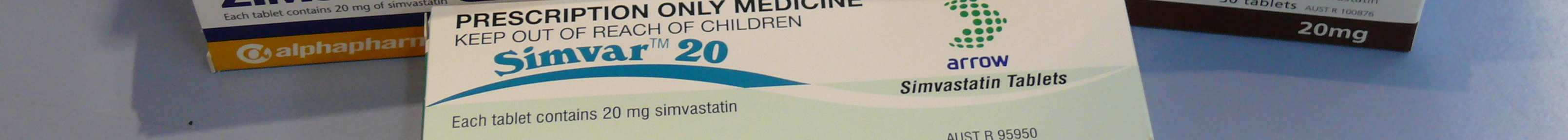

5.4.1 Rate of switching..................................................................................................... 80

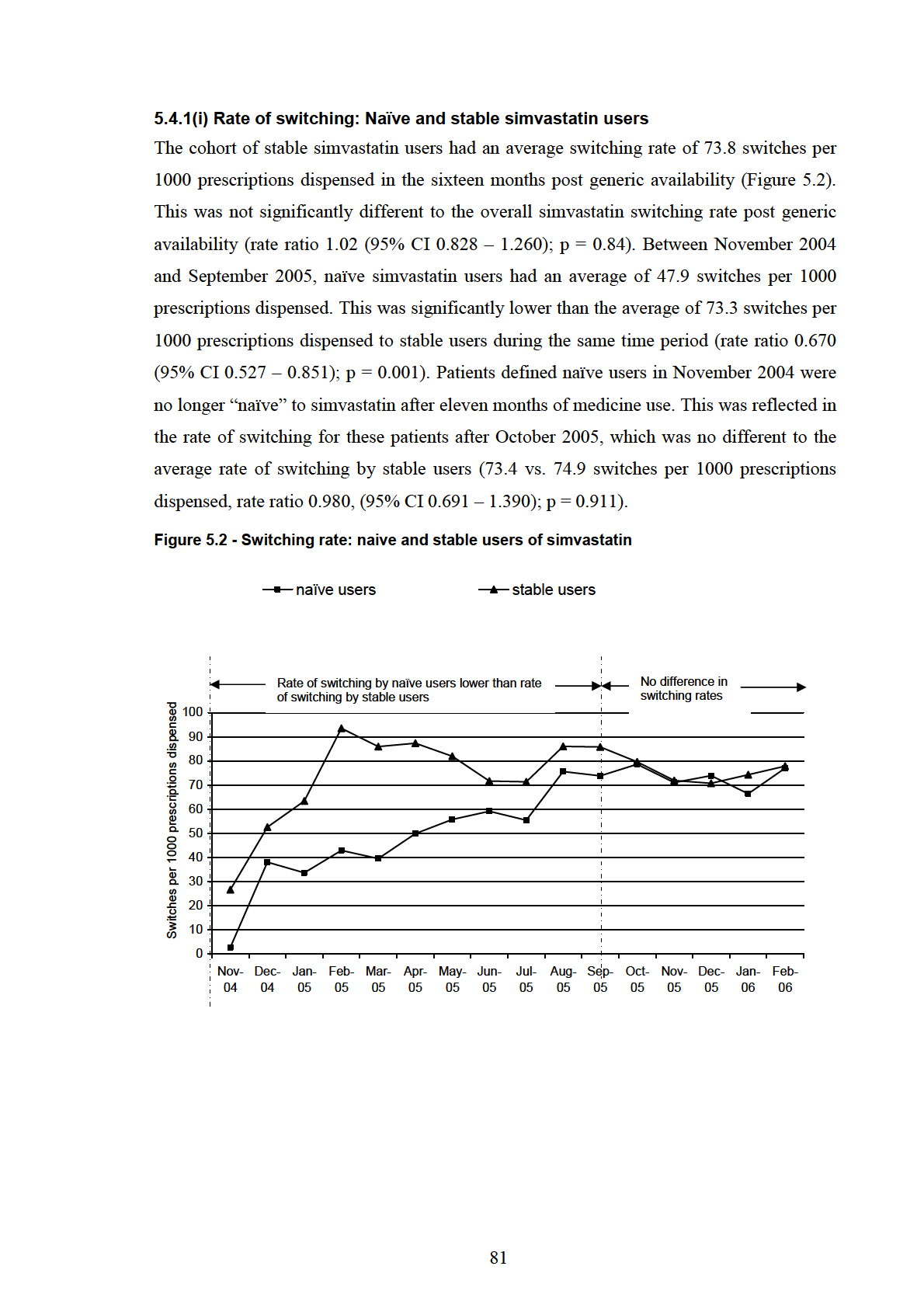

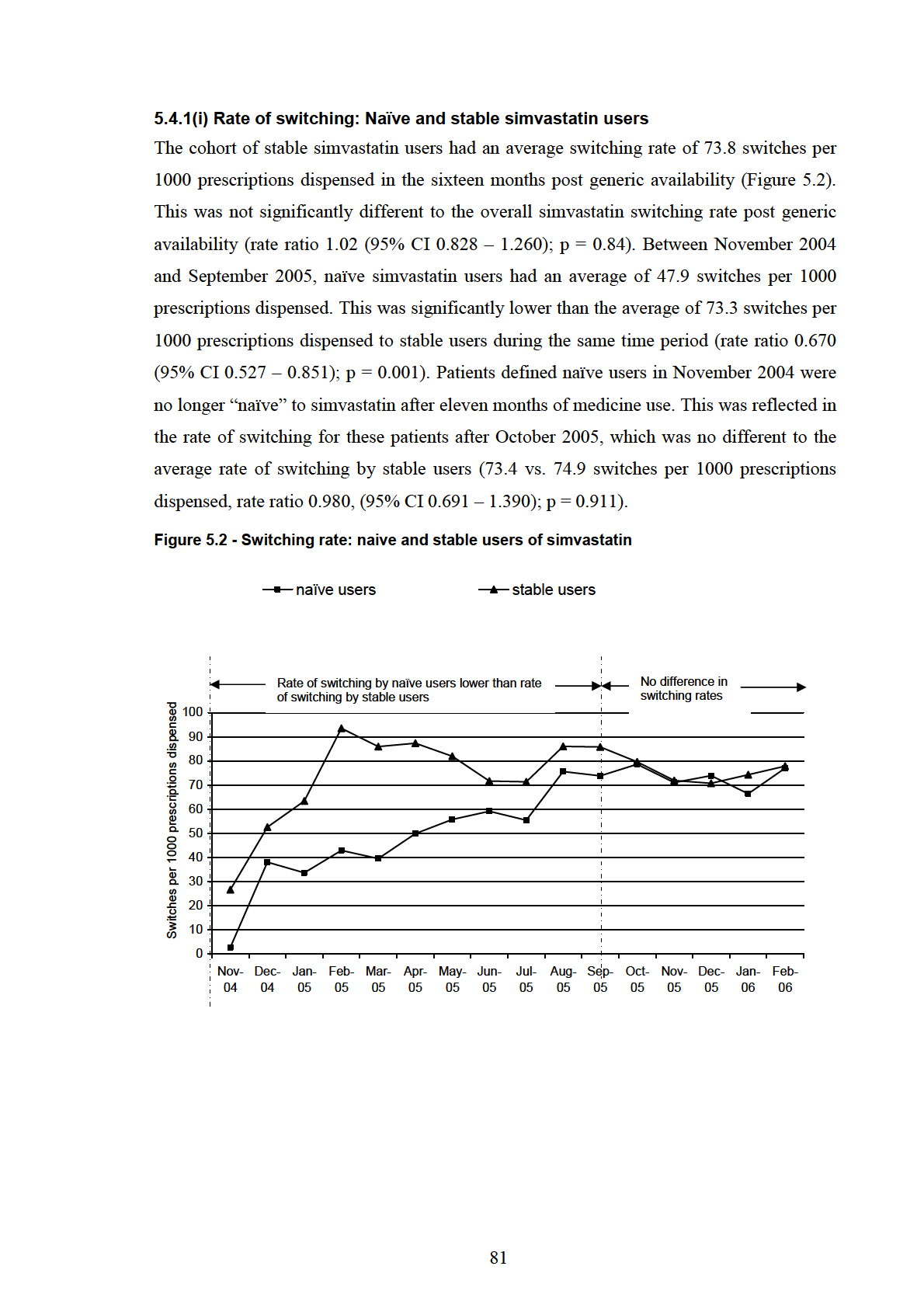

5.4.1(i) Rate of switching: Naïve and stable simvastatin users .................................... 81

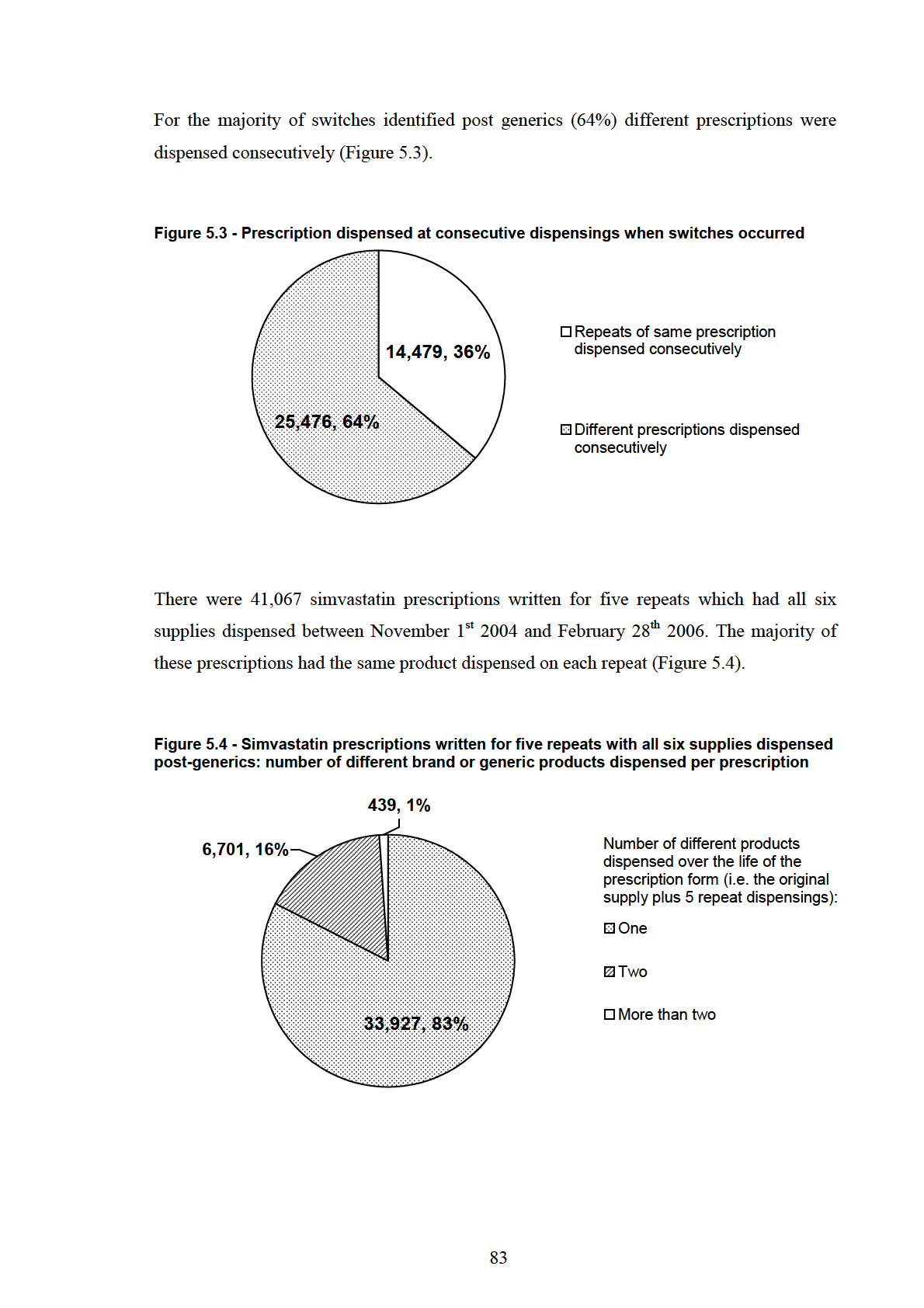

5.4.2 Patients with and without switches ......................................................................... 82

5.5 Discussion ..................................................................................................................... 84

5.6 Conclusions................................................................................................................... 86

Chapter 6: Analysis of the extent of brand switching for six medicines: atenolol,

citalopram, enalapril, metformin, omeprazole and ramipril......................................... 87

6.1 Introduction.................................................................................................................. 87

6.2 Aims............................................................................................................................... 88

6.3 Methods......................................................................................................................... 89

6.3.1 Methods: Part 1 – Background analysis.................................................................. 90

iii

6.3.2 Methods: Part 2 - The extent of brand switching on repeats of individual

prescriptions; a “prescription-level” analysis................................................................... 91

6.3.2(i) Identification of dispensings for individual prescriptions ............................... 91

6.3.2(ii) Identification of switches for the prescription-level analysis ......................... 92

6.3.3 Methods: Part 3 - Number of brand switches per patient; a “patient-level” analysis

.......................................................................................................................................... 92

6.3.3(i) Brand substitution status of patients ................................................................ 93

6.3.3(ii) Statistical analysis........................................................................................... 93

6.4 Results ........................................................................................................................... 94

6.4.1 Results: Part 1 – Background analysis .................................................................... 94

6.4.1(i) Major PBS listing changes for the study medicines ........................................ 94

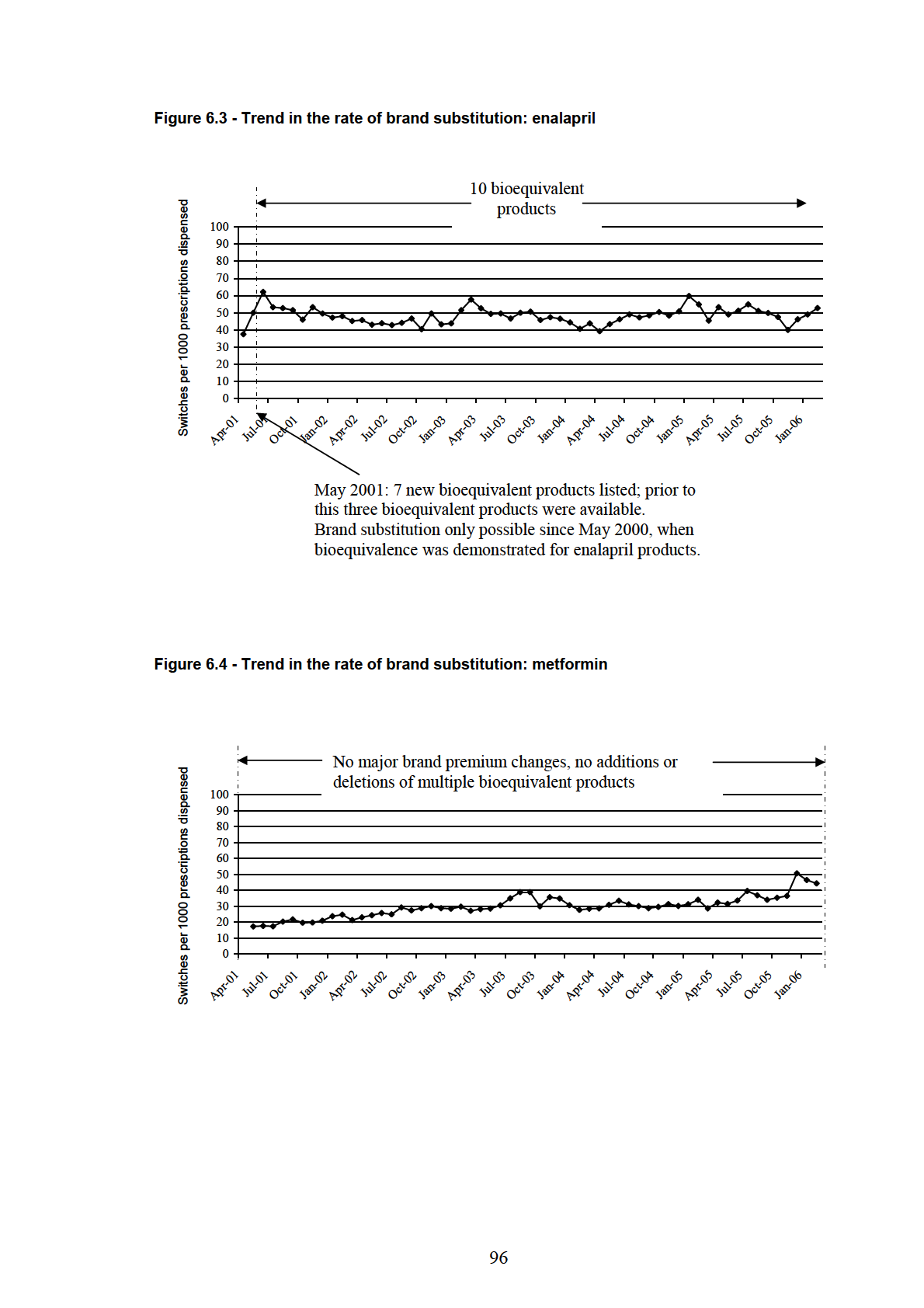

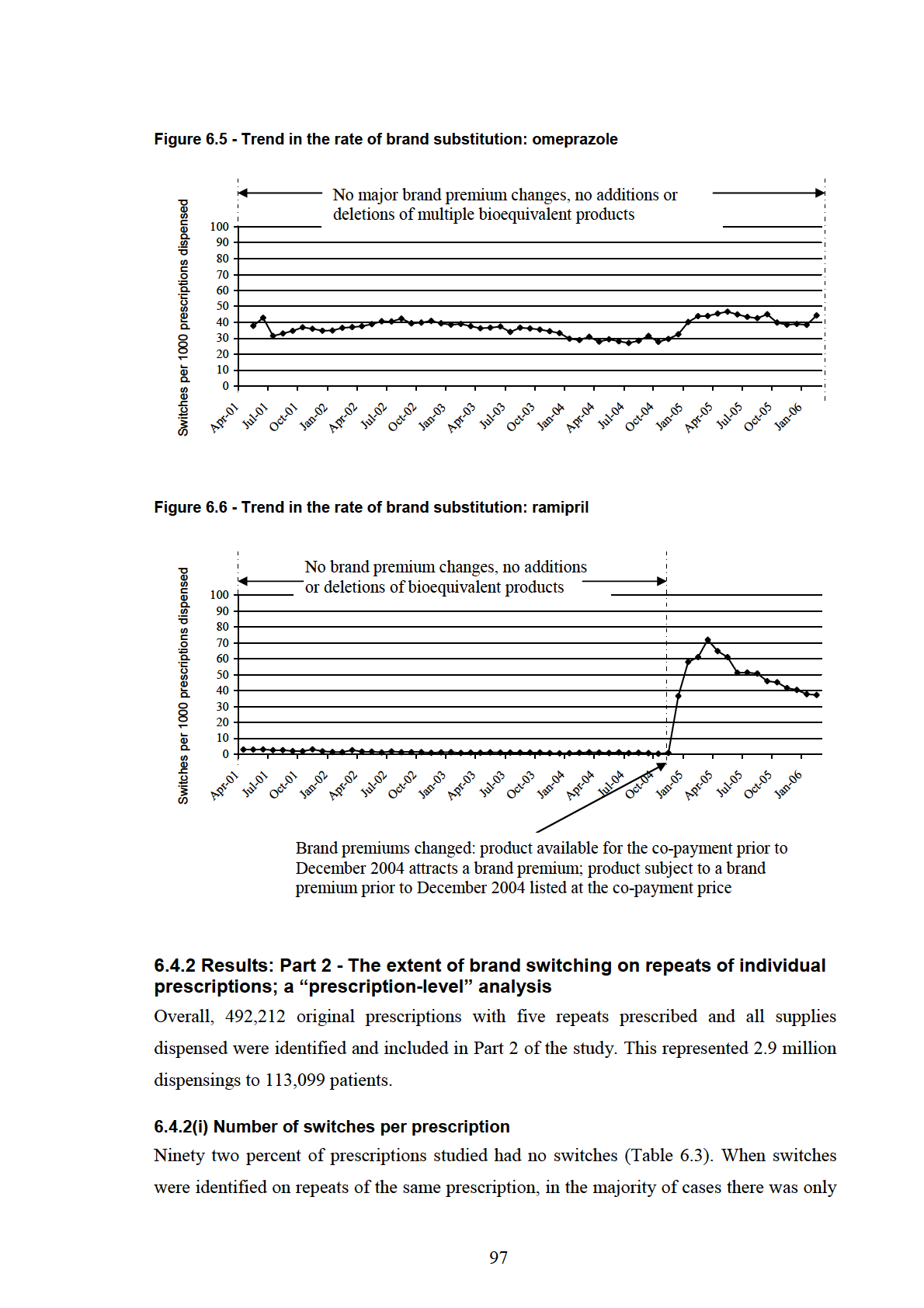

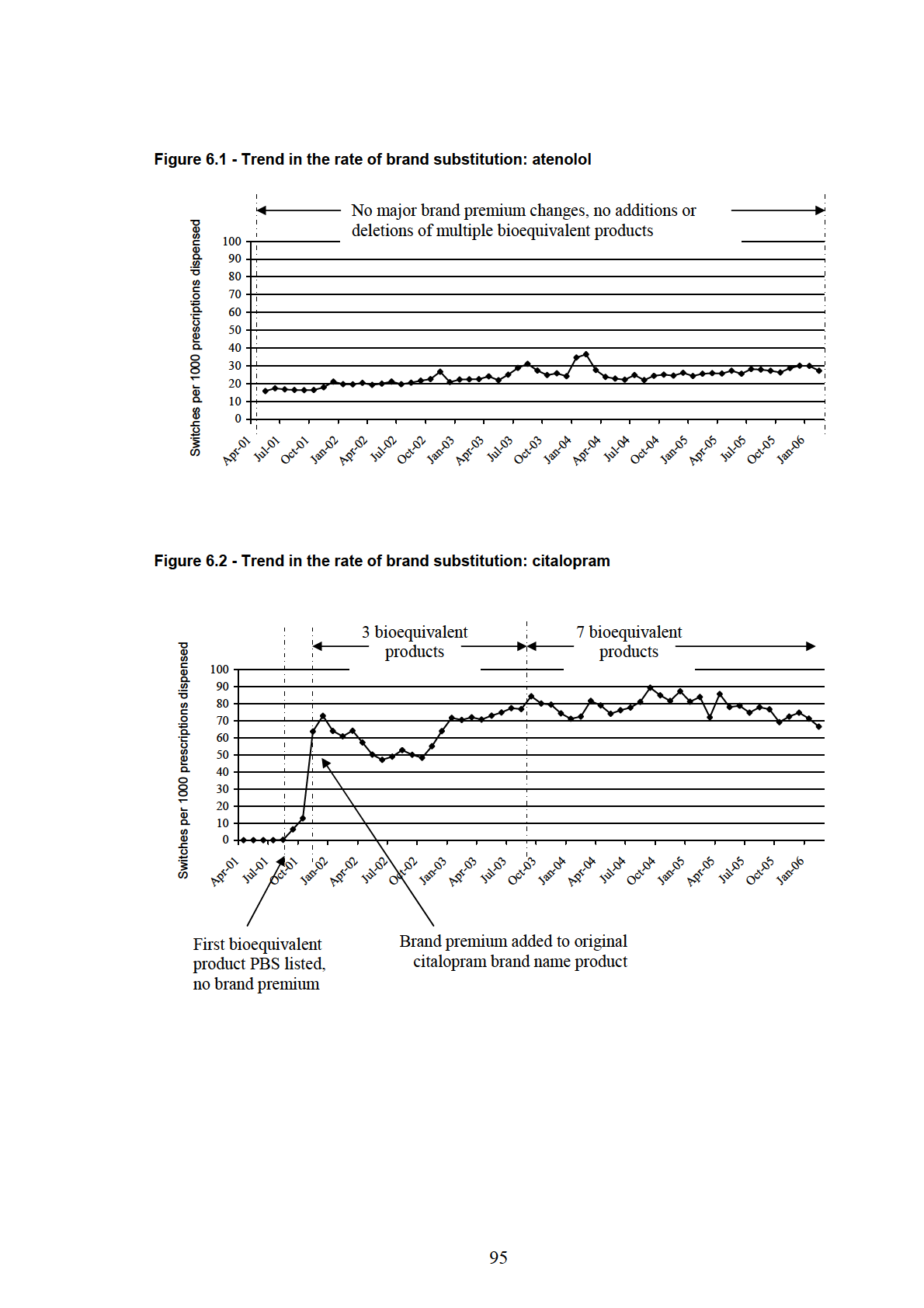

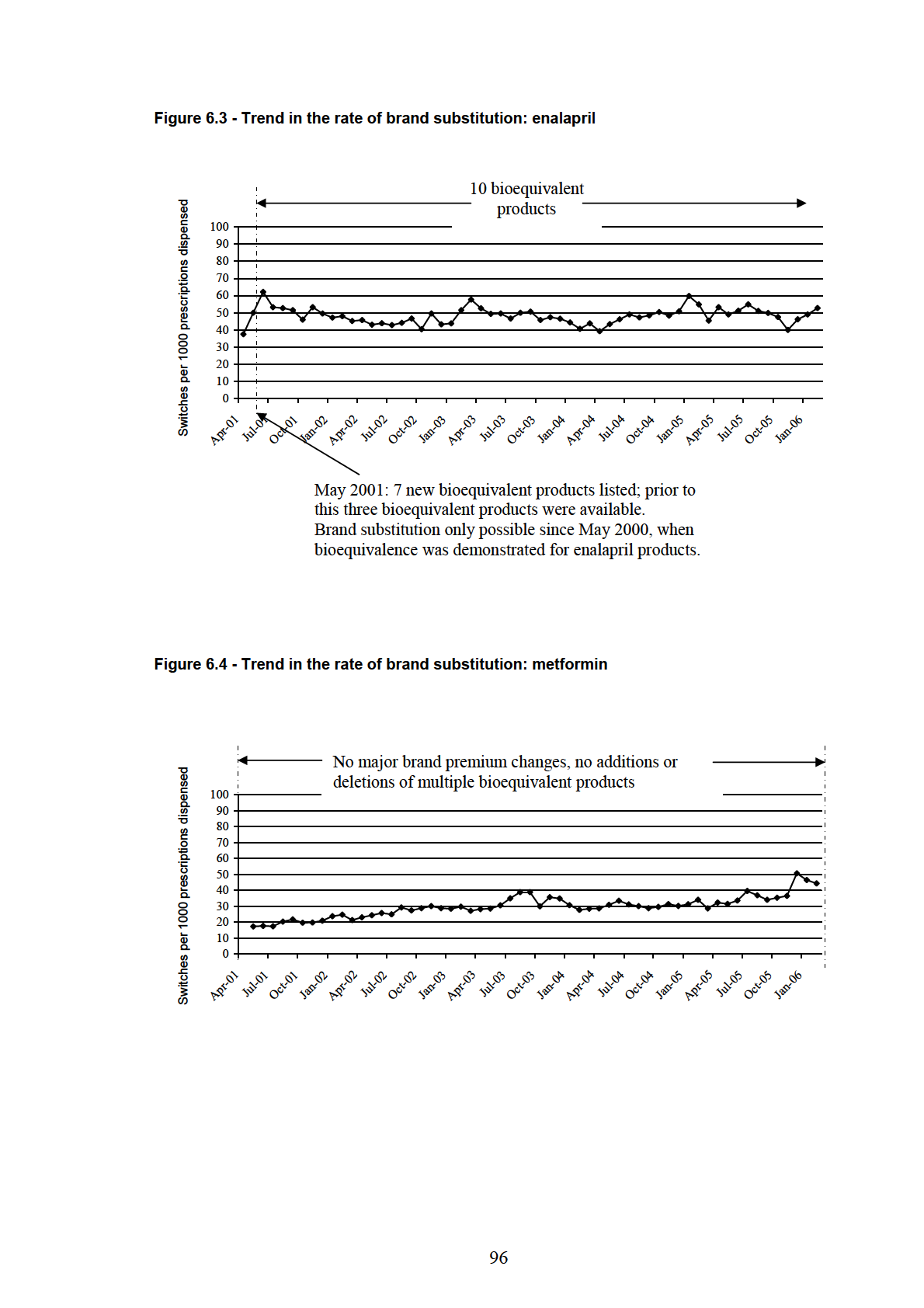

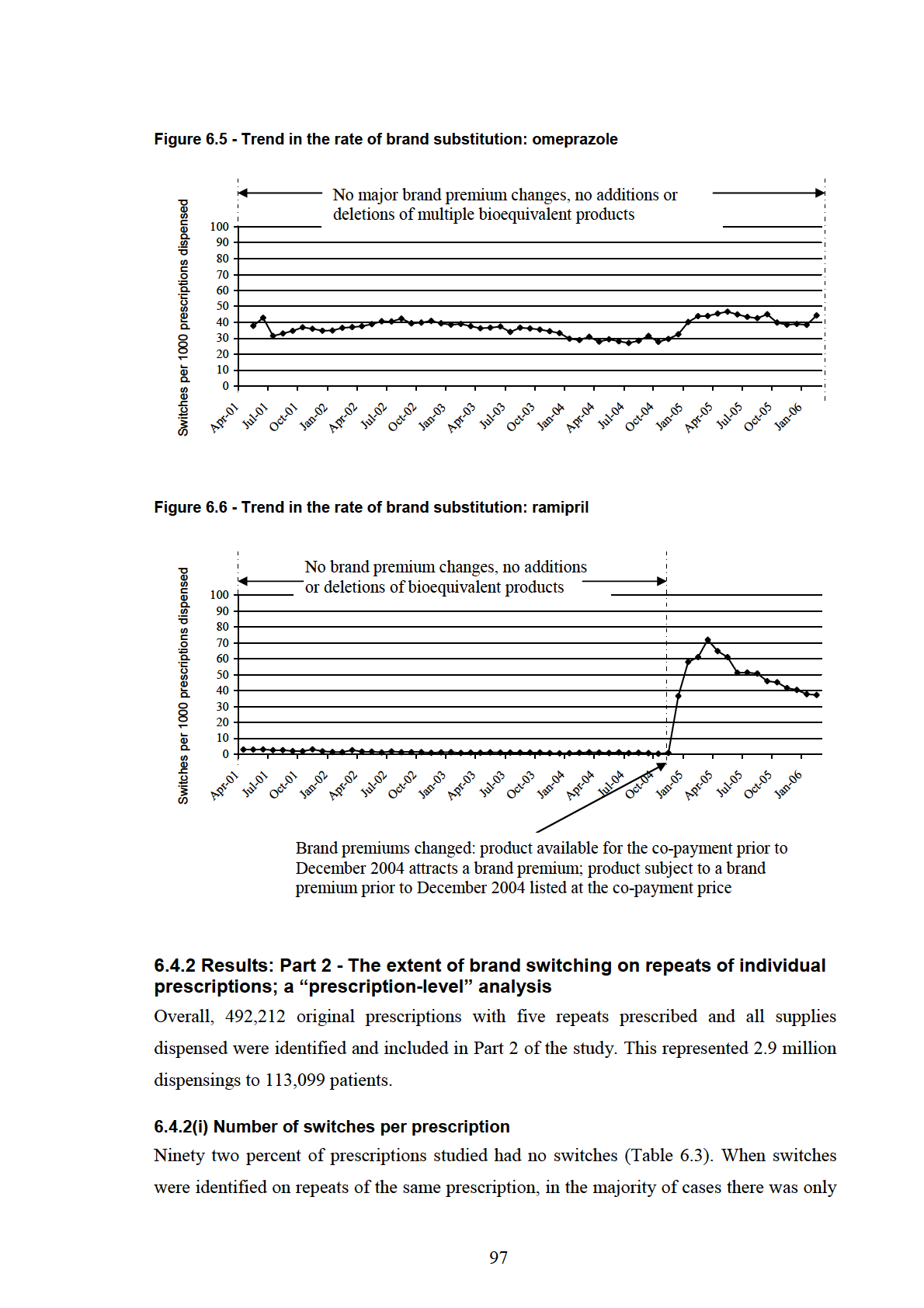

6.4.1(ii) Rate of switching ............................................................................................ 94

6.4.2 Results: Part 2 - The extent of brand switching on repeats of individual

prescriptions; a “prescription-level” analysis................................................................... 97

6.4.2(i) Number of switches per prescription ............................................................... 97

6.4.3 Results: Part 3 - Number of brand switches per patient; a “patient-level” analysis99

6.4.3(i) Brand substitution status of patients ................................................................ 99

6.4.3(ii) Comparison of multiple switchers and non-switchers.................................. 101

6.4.3(iii) Comparison of multiple switchers and brand substitution patients............. 102

6.4.3(iv) Brand substitution status and product received at initial dispensing ........... 103

6.5 Discussion ................................................................................................................... 104

6.5.1 Rate of switching between brand and generic products........................................ 104

6.5.2 The extent of brand switching on repeats of individual prescriptions; the

“prescription-level” analysis .......................................................................................... 105

6.5.3 The number of brand switches per patient; the “patient-level” analysis............... 106

6.5.4 Strengths and limitations of the study................................................................... 108

6.6 Conclusions................................................................................................................. 110

Chapter 7: The extent of brand substitution for patients using multiple medicines . 111

7.1 Introduction................................................................................................................ 111

7.2 Aims............................................................................................................................. 111

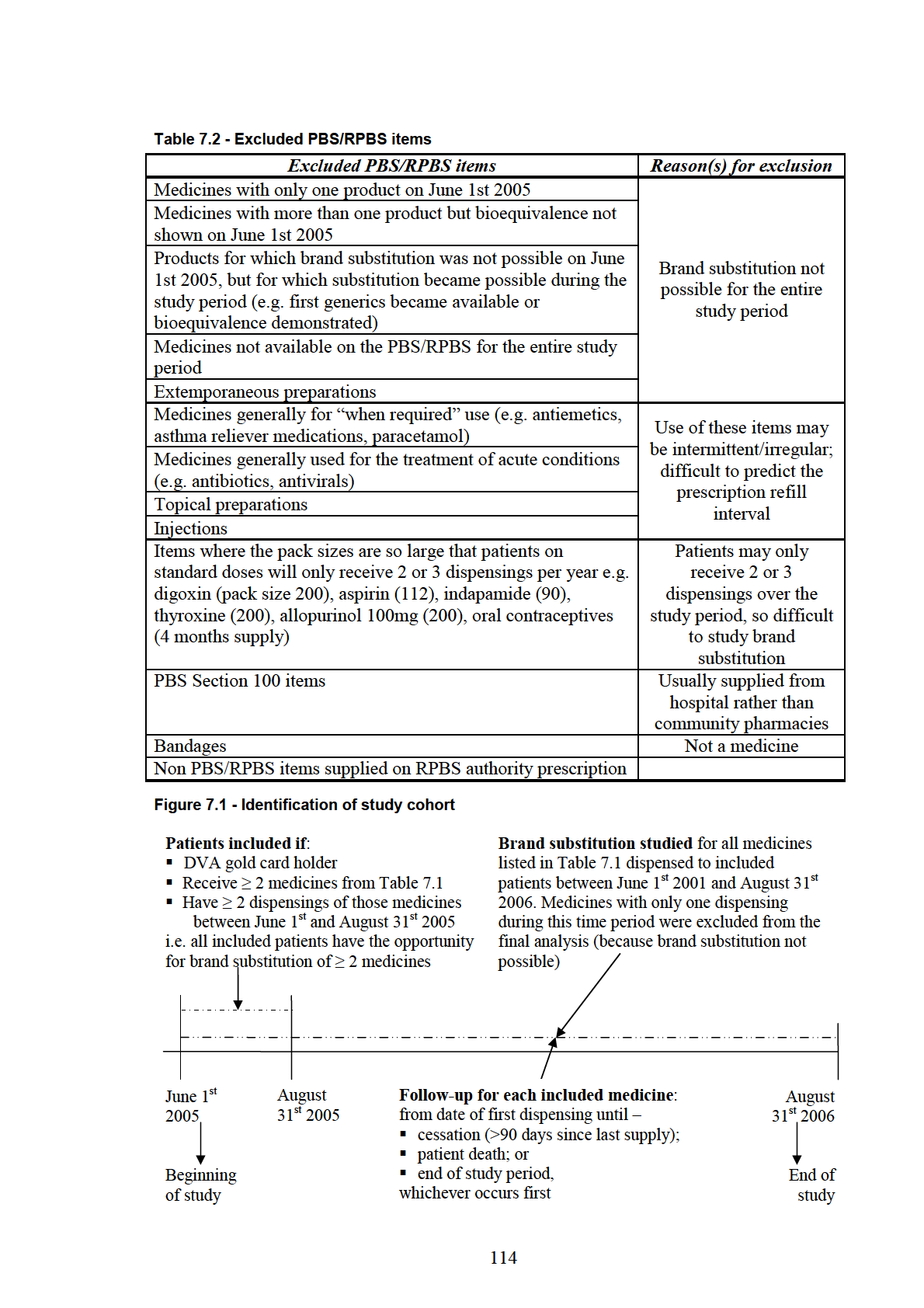

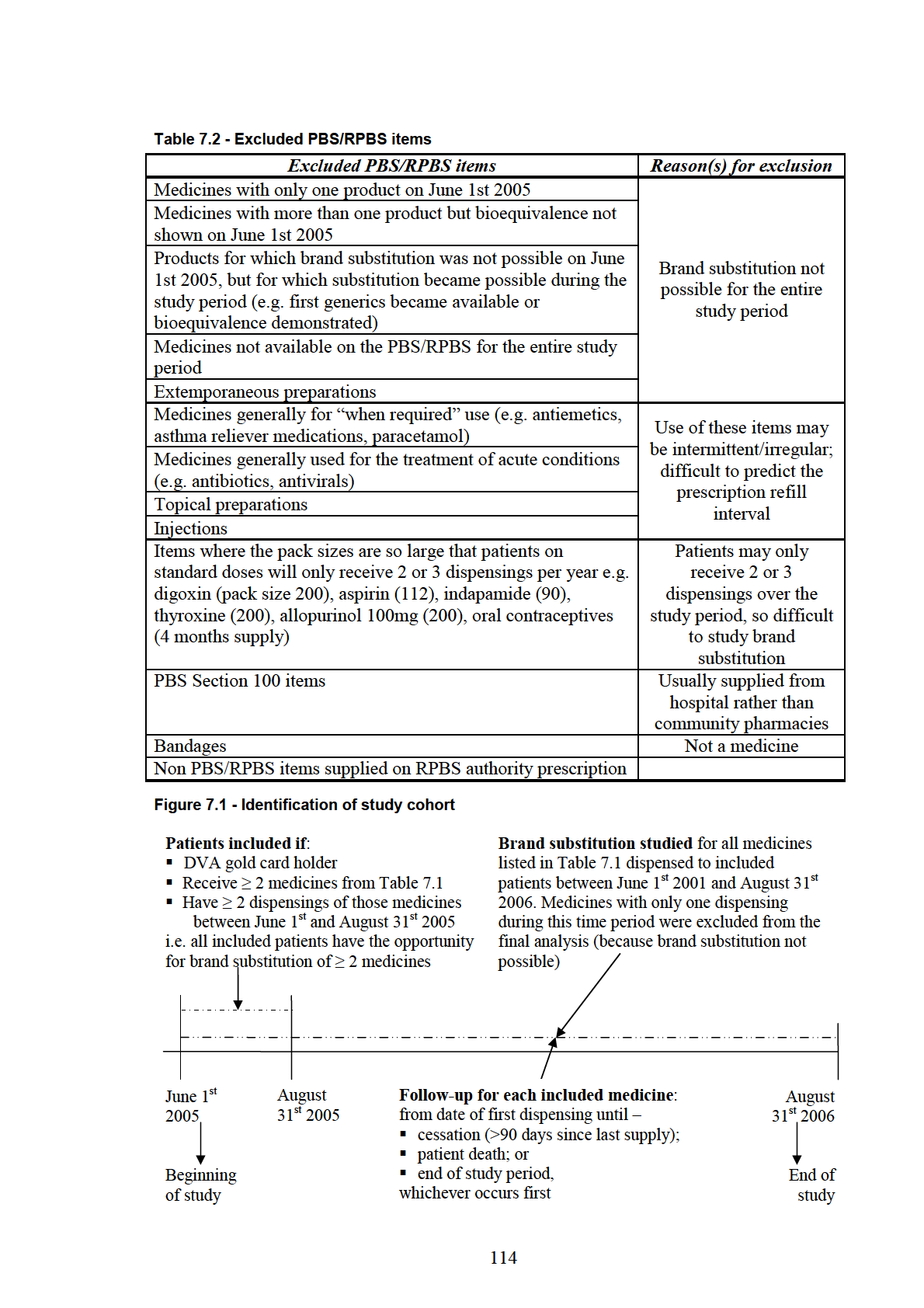

7.3 Methods....................................................................................................................... 112

7.3.1 Study period and study medicines......................................................................... 112

7.3.2 Patient inclusion criteria........................................................................................ 112

iv

7.3.3 Identification of switches for each included medicine.......................................... 115

7.3.4 Identification of patient characteristics associated with multiple switches .......... 115

7.3.5 Statistical analysis ................................................................................................. 117

7.4 Results ......................................................................................................................... 117

7.4.1 Multivariate analysis: comparison of patients with multiple switches and patients

with no switches ............................................................................................................. 118

7.4.2 Multivariate analysis: comparison of patients with multiple switches and patients

with a single brand substitution (but no medicines with multiple switches) ................. 120

7.4.3 Multivariate analysis: comparison of patients with multiple switches for two or

more medicines and patients with no switches during follow-up .................................. 121

7.5 Discussion ................................................................................................................... 123

7.6 Conclusions................................................................................................................. 127

Chapter 8: Discussion and conclusions.......................................................................... 128

8.1 Patients at risk of having multiple brand substitutions ......................................... 129

8.1.1 Strategies to avoid multiple brand substitutions ................................................... 130

8.2 Continued and future evaluations of the minimum pricing and brand substitution

policies............................................................................................................................... 133

8.3 Overall conclusions .................................................................................................... 135

References......................................................................................................................... 137

Appendix 1.1 – Publication arising from this thesis ..................................................... 152

Appendix 1.2 – Publication arising from this thesis ..................................................... 156

Appendix 1.3 – Publication arising from this thesis ..................................................... 162

Appendix 4.1 - Department of Veterans’ Affairs administrative claims datasets ..... 169

v

List of figures

Figure 1.1 - Example of the brand substitution policy: simvastatin ...................................... 2

Figure 2.1 - Interdependence of the four objectives of Australia's National Medicines

Policy ..................................................................................................................................... 5

Figure 2.2 - Supply and demand curve ................................................................................ 15

Figure 2.3 - Increasing Government cost of PBS subsidy................................................... 21

Figure 2.4 - Major PBS and RPBS co-payment changes .................................................... 23

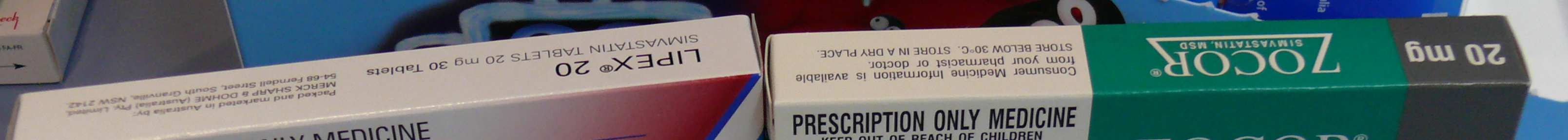

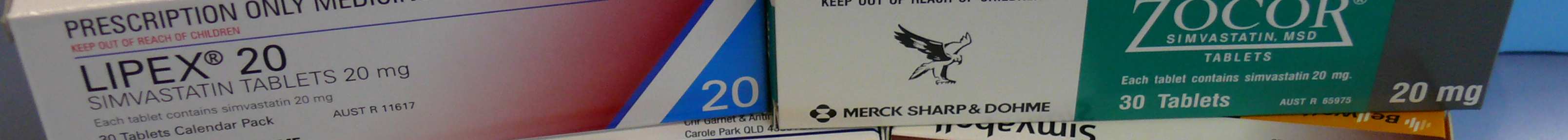

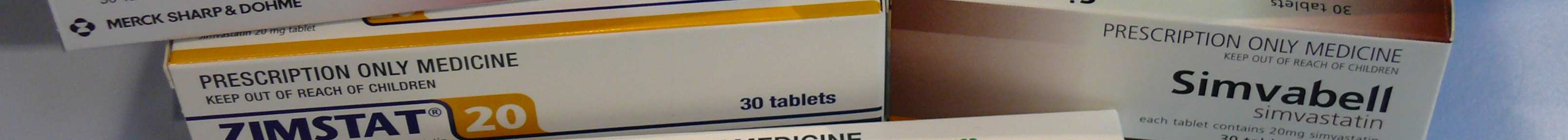

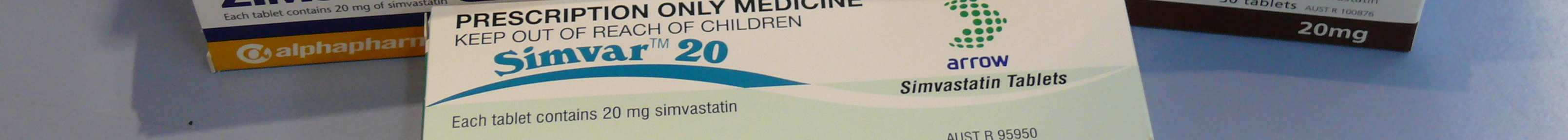

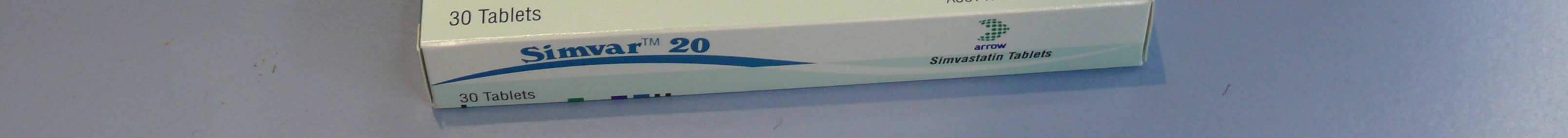

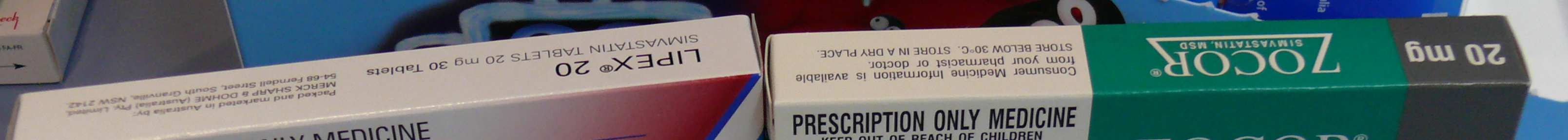

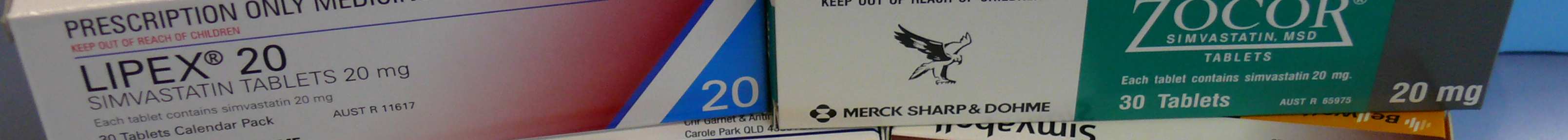

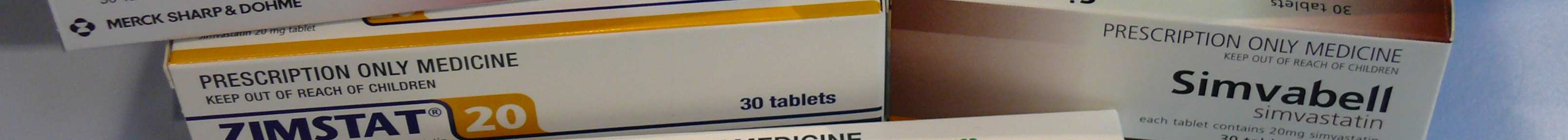

Figure 3.1 - Simvastatin packaging: appearance of different brand and generic products.. 65

Figure 5.1 - Simvastatin switching rate ............................................................................... 80

Figure 5.2 - Switching rate: naive and stable users of simvastatin...................................... 81

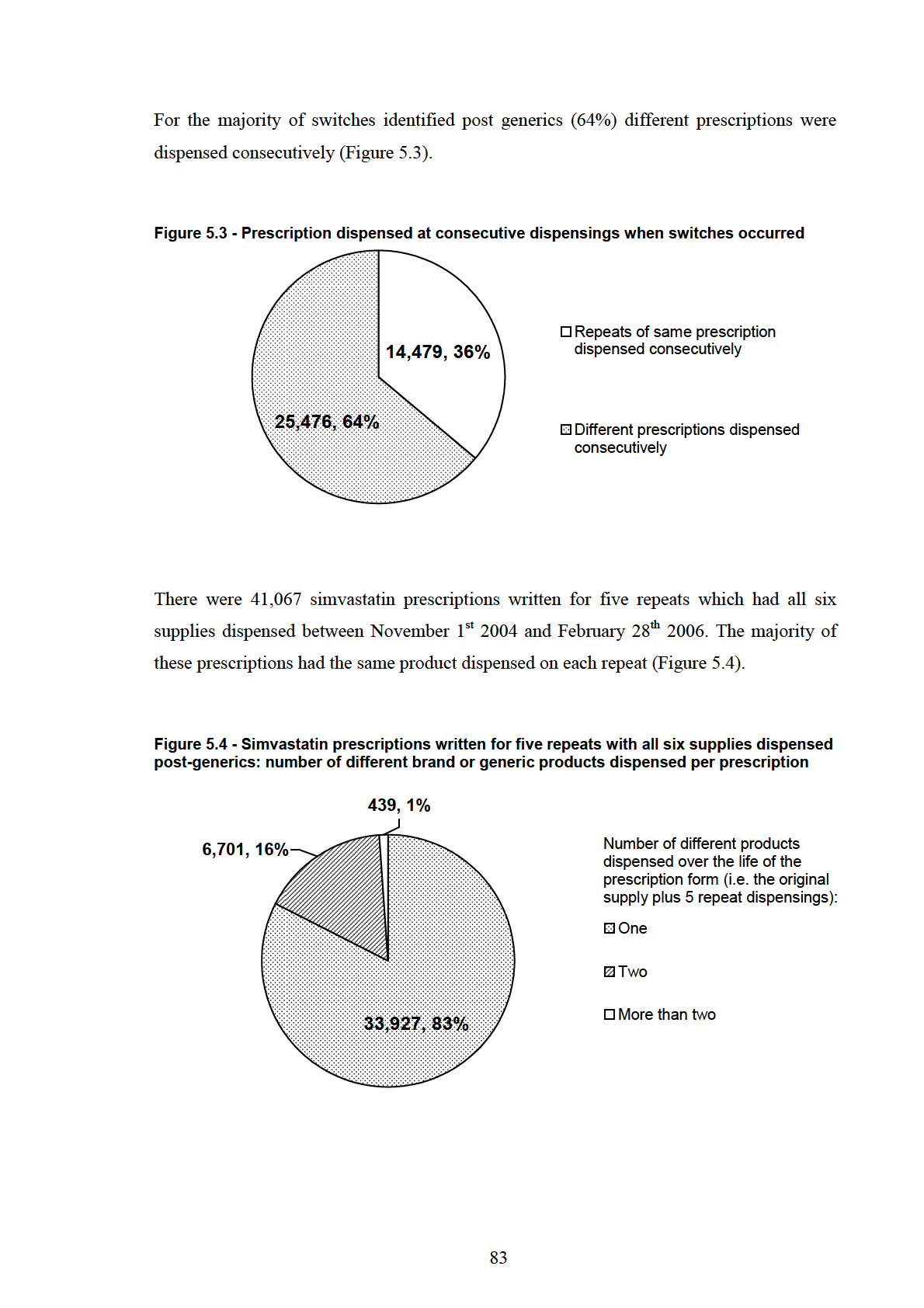

Figure 5.3 - Prescription dispensed at consecutive dispensings when switches occurred... 83

Figure 5.4 - Simvastatin prescriptions written for five repeats with all six supplies

dispensed post-generics: number of different brand or generic products dispensed per

prescription .......................................................................................................................... 83

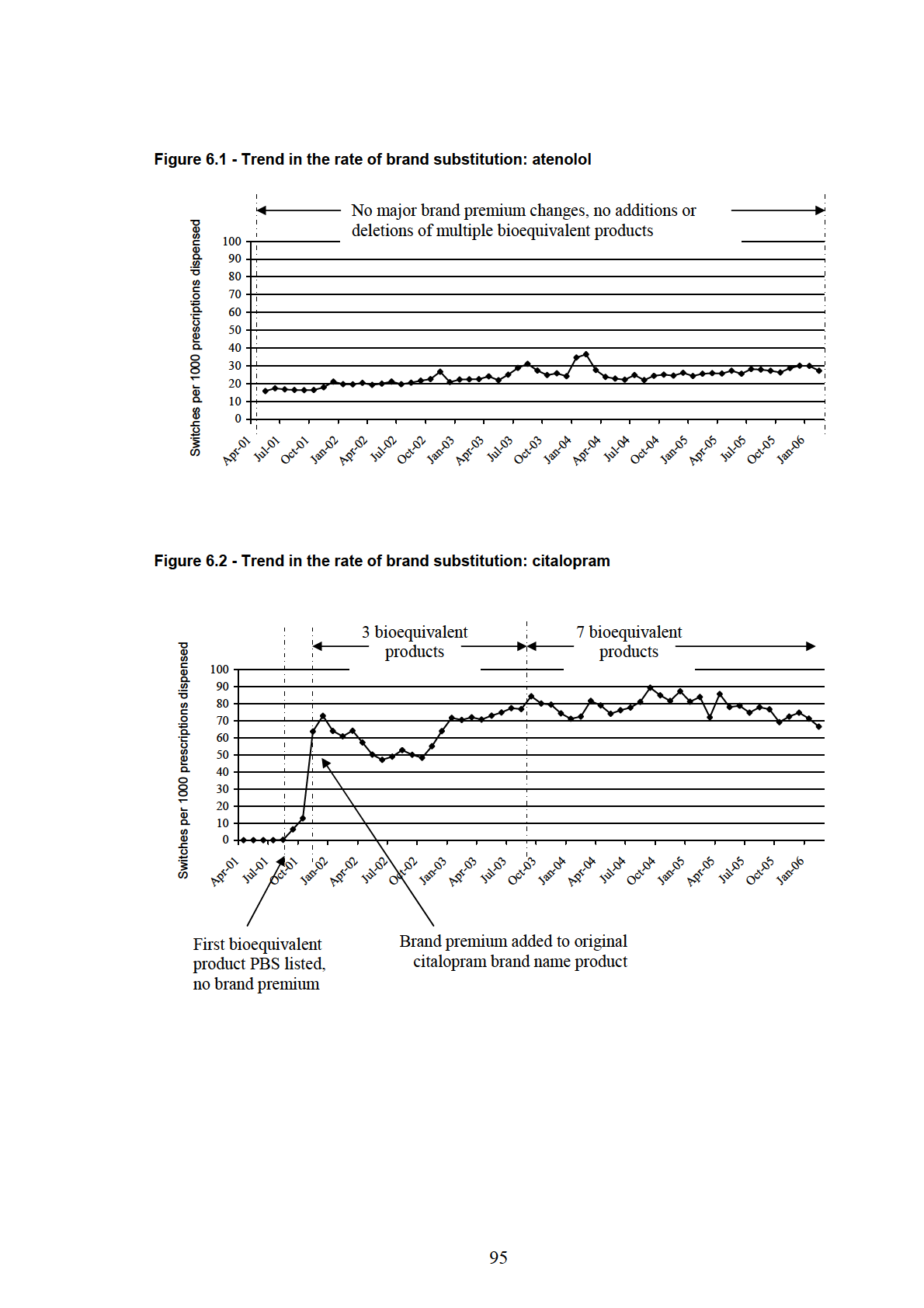

Figure 6.1 - Trend in the rate of brand substitution: atenolol .............................................. 95

Figure 6.2 - Trend in the rate of brand substitution: citalopram.......................................... 95

Figure 6.3 - Trend in the rate of brand substitution: enalapril ............................................. 96

Figure 6.4 - Trend in the rate of brand substitution: metformin .......................................... 96

Figure 6.5 - Trend in the rate of brand substitution: omeprazole ........................................ 97

Figure 6.6 - Trend in the rate of brand substitution: ramipril .............................................. 97

Figure 7.1 - Identification of study cohort ......................................................................... 114

vi

List of tables

Table 3.1 - Multiple brand and generic products: different trade names for simvastatin.... 65

Table 5.1 - Simvastatin: timeline of PBS/RPBS listing of brand and generic products...... 76

Table 5.2 - Simvastatin: time between consecutive dispensings ......................................... 78

Table 5.3 - Patients dispensed simvastatin: factors associated with being a multiple

switcher compared to a non-switcher .................................................................................. 82

Table 5.4 - Patients dispensed simvastatin: factors associated with having multiple

switches compared to one or two switches .......................................................................... 82

Table 6.1 - Study medicines ................................................................................................ 89

Table 6.2 - Time between consecutive dispensings for the study medicines ...................... 91

Table 6.3 - Prescriptions with and without switches ........................................................... 98

Table 6.4 - Number of products dispensed on prescriptions with multiple switches .......... 98

Table 6.5 - Gender, age and duration of follow-up for patients included in Part 3 of the

study..................................................................................................................................... 99

Table 6.6 - Brand substitution status of patients included in Part 3 of the study .............. 100

Table 6.7 - Rate ratio (95% confidence interval) of brand substitution status comparisons

for patients using each medicine........................................................................................ 100

Table 6.8 - Factors associated with being a multiple switcher compared to a non-switcher

........................................................................................................................................... 101

Table 6.9 - Factors associated with being a multiple switcher compared to having a single

brand substitution............................................................................................................... 102

Table 6.10 - Product supplied at initial dispensing and number of switches during follow-

up ....................................................................................................................................... 103

vii

Table 7.1 - PBS and RPBS medicines eligible for inclusion............................................. 113

Table 7.2 - Excluded PBS/RPBS items ............................................................................. 114

Table 7.3 - Included patients.............................................................................................. 117

Table 7.4 – Patients with multiple switches: number of medicines with multiple switches

........................................................................................................................................... 118

Table 7.5 - Multivariate comparison of patients with multiple switches for one or more

medicine and patients with no switches for any medicine................................................. 119

Table 7.6 - Multivariate comparison of patients with multiple switches for one or more

medicine and patients with a single brand substitution for one or more medicines .......... 120

Table 7.7 - Multivariate comparison of patients with multiple switches for two or more

medicines and patients with no switches for any medicine ............................................... 122

viii

Abbreviations used throughout the text

ABS

Australian Bureau of Statistics

ACE

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme

ADEC

Australian Drug Evaluation Committee

ADGP

Australian Divisions of General Practice

ADRAC

Adverse Drug Reactions Advisory Committee

AMA

Australian Medical Association

APAC

Australian Pharmaceutical Advisory Council

ARTG

Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods

ASGC

Australian Standard Geographic Classification

AUC

Area Under the Curve

CI

Confidence Interval

Cmax

Maximum plasma concentration

DVA

Department of Veterans’ Affairs

GP

General Practitioner

H2

Histamine-2

HMG-CoA

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A

HMO

Health Maintenance Organisation

HMR

Home Medicines Review

IRSD

Index of Relative Socio-economic Disadvantage

NPS

National Prescribing Service

OECD

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

OTC

Over the Counter

P3

Pharmaceuticals Partnerships Program

PBAC

Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee

PBPA

Pharmaceutical Benefits Pricing Authority

PBS

Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme

ix

Abbreviations used throughout the text – continued

PHARM

Pharmaceutical Health and Rational Use of Medicines

PIIP

Pharmaceutical Industry Investment Program

PPI

Proton Pump Inhibitor

PSA

Pharmaceutical Society of Australia

QUM

Quality Use of Medicines

RCT

Randomised Controlled Trial

RPBS

Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme

SD

Standard Deviation

SHPA

Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia

SSRI

Selective Serotonin Re-uptake Inhibitor

TGA

Therapeutic Goods Administration

WHO

World Health Organisation

x

Summary

Since December 1994, a brand substitution policy has operated on the Pharmaceutical

Benefits Scheme (PBS) and Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (RPBS), the

nationally funded schemes for medicine subsidy in Australia. Patients can receive a brand

or generic product other than the one prescribed if products are bioequivalent and the

prescription is not marked “substitution not permitted”. Ideally patients should remain on

the same product following initial brand substitution; however there is no limit to the

number of brand substitutions. There are concerns that multiple product changes occur,

with the potential to confuse patients and compromise the quality use of medicines (QUM).

Increased use of generics in Australia is encouraged; however, the brand substitution

policy has not been evaluated since implementation.

The studies in this thesis evaluated implementation of the brand substitution policy from

Australia’s National Medicines Policy perspective, by studying the frequency of brand

substitution for government subsidised medicines and the extent of switching between

products by cohorts of individuals. Administrative claims data for government subsidised

medicine dispensings were used.

In the first and second chapters of the thesis, Australia’s National Medicines Policy and the

systems for subsidy and supply of medicines in Australia are described. The concepts of

supply and demand for medicines are introduced, and PBS policies designed to influence

supply and demand for medicines, including the brand substitution policy, are discussed.

The potential impact of these policies on achieving QUM is discussed in Chapter 3 and

gaps in knowledge regarding implementation of brand substitution are identified. In

Chapter 4 suitable research methods and data sources within which to address the research

gaps are identified.

xi

The first study in this thesis, reported in Chapter 5, characterised brand substitution using

the example of simvastatin, a medicine for which brand substitution was first possible in

2004. Trends in the rate of brand substitution and the extent of brand substitution per

patient were examined. Over 90% of patients in this analysis had two or less switches; only

9% had multiple switches. Simvastatin patients with multiple switches were more likely to

have had more prescribers, dispensing pharmacies and original prescriptions than other

patients (p < 0.0001)

The study in Chapter 6 further characterised implementation of the brand substitution

policy using six medicine examples. Trends in the rate of brand substitution for these

medicines were examined and the number of brand substitutions per prescription form and

per patient identified. While switching occurred for all products, analysis of individual

prescriptions showed that 92% of prescription forms had the same product supplied on

each repeat dispensing. Analysis by patient showed over 80% of patients either had no

switches or only a single brand substitution, confirming the results reported in Chapter 5.

Patients with multiple switches were more likely to receive a product with a brand

premium at their initial dispensing.

To complete the brand substitution picture, the study in Chapter 7 examined the extent of

brand substitution for all medicines used by a cohort of patients on multiple medicines.

Amongst this cohort, 83% of patients either had no switches or only a single brand

substitution during follow-up for all medicines received. Patients at risk of having multiple

brand substitutions had more prescription medicines, hospital admissions, dispensing

pharmacies, prescribers and longer follow-up than other patients (p < 0.0001).

In Chapter 8, implementation of the brand substitution policy from the National Medicines

Policy perspective is discussed. The overall conclusion from the findings of the studies

reported in this thesis is that the minimum pricing policy and brand substitution are

implemented in the manner intended. They facilitate consumer access to cheaper medicines

without resulting in multiple switches for over 80% of patients. Initiatives to reduce

multiple switching amongst patients identified as being at increased risk of having multiple

switches would further support implementation of the brand substitution policy.

xii

Statement of originality

I declare that this thesis presents work carried out by myself and does not incorporate

without acknowledgement any material previously submitted for a degree or diploma in

any university. To the best of my knowledge it does not contain any materials previously

published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the text. All

substantive contributions by others to the work presented, including jointly authored

publications, is clearly acknowledged.

Lisa Kalisch

Date

xiii

Acknowledgement

I thank my PhD supervisors, Libby Roughead and Andrew Gilbert for their support along

this journey. Your encouragement, advice and feedback is greatly appreciated. In particular

I thank Libby for her guidance and encouragement, and for reading (and re-reading!)

numerous drafts of papers and this thesis.

I thank the Department of Veterans’ Affairs for supporting this research with a PhD

scholarship and for providing access to the administrative health claims data used in this

research. I thank everyone at QUMPRC for their friendship and support along the way. In

particular, I thank Emmae Ramsay for her statistical advice and assistance.

Thanks to the people who encouraged me to undertake this PhD in the first place, in

particular Lisa Spurling and my parents. Thanks mum and dad for your support and

encouragement, and for always being so proud of everything that I do. Thanks also to Paul

and Lindsay for your support from the other side of the world. And most importantly,

thankyou John for your support and encouragement, and for just being there.

xiv

Communications arising from this thesis

Work from this thesis has been presented in the following publications and conference

presentations:

Peer reviewed publications

Kalisch LM, Roughead EE, Gilbert AL. Do pharmacists adhere to brand substitution

guidelines? The example of simvastatin. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research 2007;

37(4): 292-294.

Kalisch LM, Roughead EE, Gilbert AL. Pharmaceutical brand substitution in Australia –

are there multiple switches per prescription? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public

Health 2007; 31(4): 348 – 52.

Kalisch LM, Roughead EE, Gilbert AL. Brand substitution or multiple switches

per patient? An analysis of pharmaceutical brand substitution in Australia.

Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 2008; 17(6): 620 – 25.

See Appendix 1 for copies of these publications.

xv

Conference presentations

Kalisch L, Roughead E, Gilbert A. Brand and generic substitution in Australia: are patients

switched between products multiple times? Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 2007;

16(S2): S55 – S56.

Kalisch L, Roughead E, Gilbert A. Switching between brand name and generic medicines -

are there multiple switches per prescription? In: Davey A and Milne R, editors. Annual

conference of the Australasian Pharmaceutical Science Association; Adelaide; 2006.

Kalisch L, Roughead E, Gilbert A. Switching between brand name and generic medicines:

the example of simvastatin. In: Day R and Boyd R, editors. National Medicines

Symposium. Quality Use of Medicines: Balancing beliefs, benefits and harms; Canberra;

2006.

Kalisch L, Roughead E, Gilbert A. Brand switching following patent expiry of simvastatin

and introduction of generic alternatives. In: Davis E and Sobey C, editors. Proceedings of

the joint meeting of the Australasian Society of Clinical and Experimental Pharmacologists

and Toxicologists (ASCEPT) and the Australasian Pharmaceutical Science Association

(APSA); Melbourne; 2005.

Seminar presentations

Kalisch L, Roughead E, Gilbert A. Brand and generic substitution in Australia: are patients

switched between products multiple times? Presented to UniSA Vice Chancellor Peter Høj,

UniSA Pro Vice Chancellor (Health Sciences) Robyn Mc Dermott and travel scholarship

donor Mr Roy Schulz. Presentation given on 10th July 2007 at the Quality Use of

Medicines and Pharmacy Research Centre, UniSA.

Kalisch L, Roughead E, Gilbert A. Switching between brand name and generic medicines:

the example of simvastatin. Presented at Sansom Institute Research Colloquium:

Influencing medicines policy and medicine use through research; held at the University of

South Australia on August 4th 2006.

xvi

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

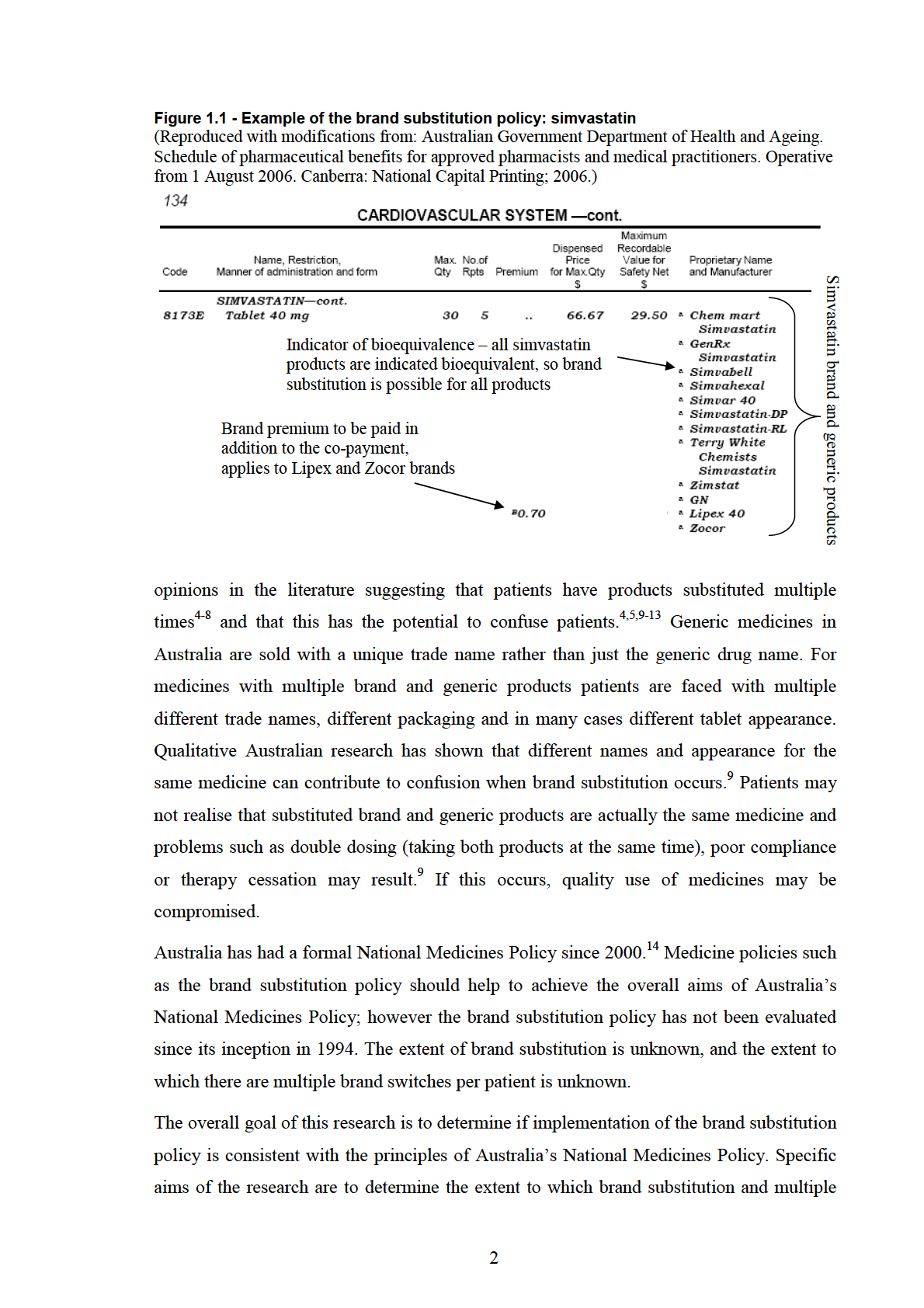

The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) and Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits

Scheme (RPBS) are nationally funded schemes for medicine subsidy in Australia. Patients

pay a fixed co-payment for subsidised medicines; the remainder of the cost is met by the

Australian government. In 1990, the minimum pricing policy was introduced to the PBS

and RPBS, and since then only the cheapest brand(s) or generic product(s) for each

medicine are available to patients at the co-payment price.1 A brand substitution policy was

introduced in December 1994 allowing brand substitution of bioequivalent products by

pharmacists at the time of dispensing, provided the prescriber hadn’t specified that brand

substitution could not occur.2,3 All brand and generic products of a medicine available for

PBS and RPBS subsidy are listed in the Schedule of Pharmaceutical Benefits. Products

with the indicator of bioequivalence (a superscript “a” next to the product name) may be

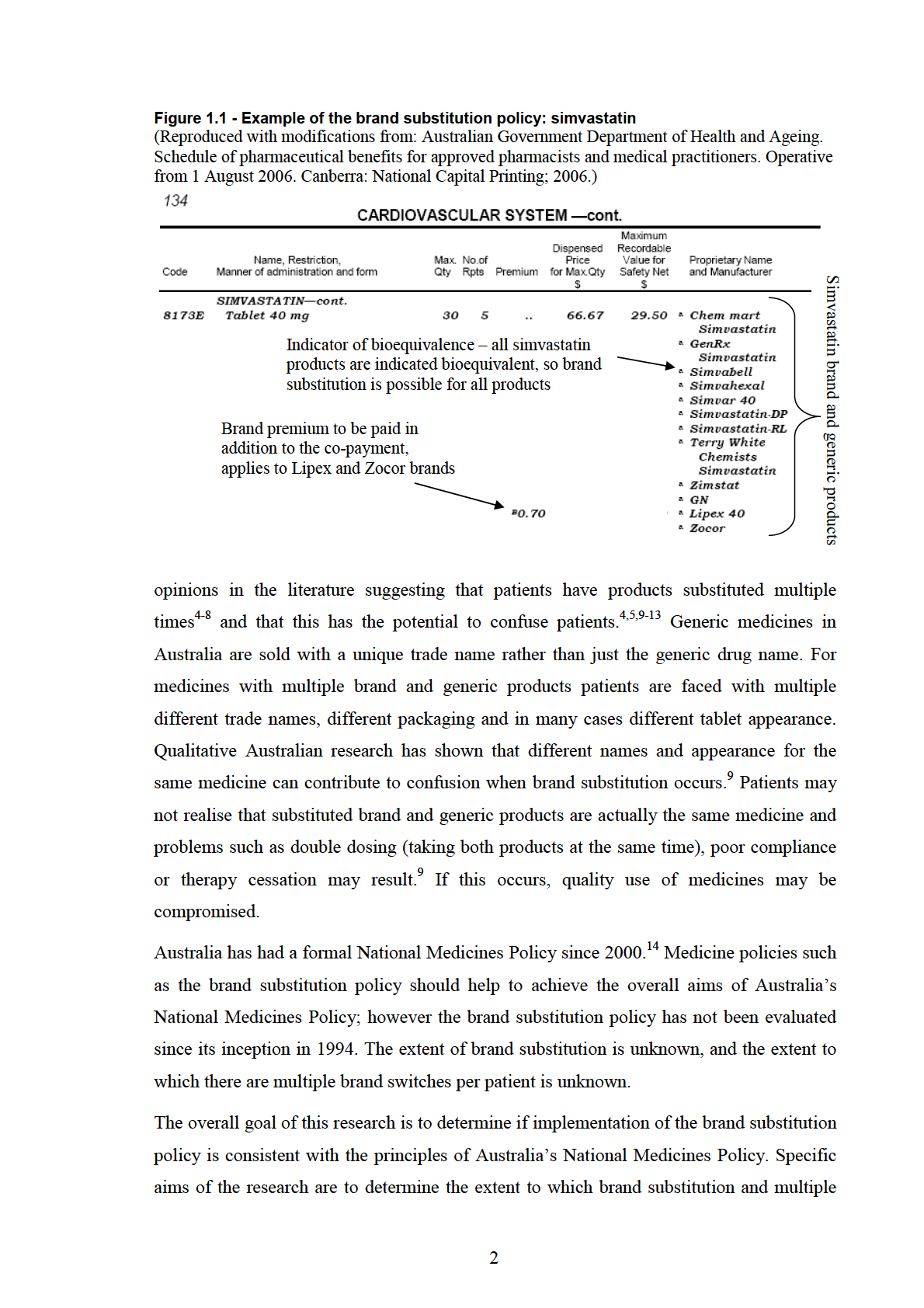

substituted (Figure 1.1). Price premiums for brands costing more than the cheapest

product(s) are shown in the Schedule of Pharmaceutical Benefits, and must be paid in

addition to the standard co-payment (see Figure 1.1).

The minimum pricing policy allows medicine manufacturers to set the price for their

product above the maximum subsidised price and sends a price signal to patients regarding

the cost of their medicines.1 The brand substitution policy facilitates use of cheaper

products, by giving consumers the opportunity to respond to the price signal associated

with more expensive brands of medicine.1 When the brand substitution policy was planned,

it was intended to facilitate substitution of cheaper generic medicines for patients who had

been prescribed brand name medicines which attracted a brand premium.1 Ideally patients

should remain on the same product following the initial brand substitution; however,

legislation does not prevent multiple brand substitutions per patient. In the years since

introduction of the brand substitution policy there have been anecdotal reports and

1

brand substitutions per patient occur; and to identify the people and situations in which

multiple brand substitutions are most likely to occur. Administrative claims data for

medicine dispensings will be used to achieve these aims.

This thesis begins with an overview of Australia’s National Medicines Policy and a

description of medicines subsidy and supply in this context.

3

CHAPTER 2

Australia’s National Medicines Policy - the medicines

framework in Australia

In this chapter Australia’s National Medicines Policy, the framework governing medicines

and their use in Australia, is described. The challenges of meeting the policy goals are

discussed and an overview of the economic theory of supply and demand is provided as a

basis for discussing factors influencing the subsidy and use of medicines. The chapter

concludes with a discussion of policies influencing supply and demand of medicines in

Australia.

2.1 Australia’s National Medicines Policy

In 1987, in recognition of the fact that formal policies were required to ensure and maintain

access to medicines of high quality, safety and efficacy and to ensure the rational use of

medicines, the World Health Organization (WHO) drafted guidelines for the development

of national drug policies.15 WHO describes a national drug policy as:

− “a commitment to a goal and a guide for action. It expresses and prioritises

the medium- to long-term goals for the pharmaceutical sector, and identifies

the main strategies for attaining them. It provides a framework within which

the activities of the pharmaceutical sector can be coordinated. It covers both

the public and the private sectors, and involves all the main actors in the

pharmaceutical field.”16

In 1989 only 14 countries had a national drug policy and by 1999 this had increased to 66

countries.16 Australia was one of the first developed countries to implement a national drug

policy,16 which is referred to in Australia as the National Medicines Policy.

Australia’s National Medicines Policy was formally implemented in 2000;14 however, a

major component of the National Medicines Policy, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme

(PBS), was implemented in the 1950s.17 Other components of the policy were also

developed many years prior to the formal introduction of the National Medicines

4

Policy.17-19 The overall aim of Australia’s National Medicines Policy is to “meet

medication and related service needs, so that both optimal health outcomes and economic

objectives are achieved.”14 To achieve this overall aim, the policy focuses on four central

objectives:

•

“timely access to the medicines that Australians need, at a cost individuals and the

community can afford;

•

medicines meeting appropriate standards of quality, safety and efficacy;

•

quality use of medicines; and

•

maintaining a responsible and viable medicines industry.”14

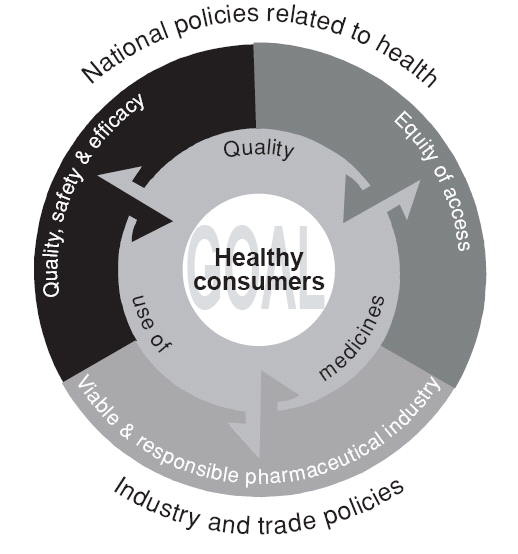

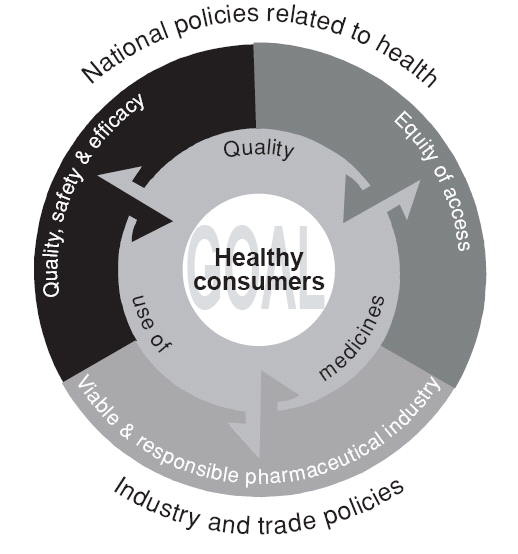

The four objectives of Australia’s National Medicines Policy are “interdependent”19 – that

is, achievement of each objective and the overall goal of the National Medicines Policy

requires each of the other objectives to be fulfilled at the same time. For example, quality

use of medicines (QUM) cannot be achieved if the access objective is not met and people

cannot afford to buy their medicines.19 If the quality, safety and efficacy objective is not

met, then it would be impossible to achieve QUM.19 Maintaining a viable medicines

industry in Australia helps ensure a reliable medicines supply and the development of new

medicines.14 The interdependence of the four objectives of the National Medicines Policy

is illustrated in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1 - Interdependence of the four objectives of Australia's National Medicines Policy

(Reproduced from: Commonwealth of Australia. The national strategy for quality use of medicines.

Plain English edition. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing; 2002.)

5

In line with the WHO guidelines for developing national drug policies, there are programs

and frameworks in place to support achieving each of Australia’s National Medicines

Policy objectives. These are discussed in detail in the next sections of this chapter.

2.1.1 Timely access to medicines at a cost individuals and the community

can afford

Access to medicines not only involves access to an adequate and reliable supply of

medicine, it also involves the ability of individuals and the community to pay for

medicines. The National Medicines Policy states that “cost should not constitute a

substantial barrier to people’s access to medicines they need”.14 The Pharmaceutical

Benefits Scheme (PBS) and the Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (RPBS), the

government subsidised schemes for supply of medicines in Australia, help to achieve this

part of the access aim.

The PBS commenced in 195017 in response to availability of medicines such as penicillin

and concerns that the majority of Australians would be unable to afford them.20 Both sides

of parliament agreed that the Commonwealth Government had a responsibility to ensure

that Australians had affordable access to medicines.17 When the PBS started, it covered

139 “lifesaving and disease preventing” medicines, available to Australians free of

charge.17,20 In 2007, over 600 medicines21 available as 2,800 different products3 were

subsidised through the PBS. Medicines available for subsidy under the PBS are listed in

the Schedule of Pharmaceutical Benefits,a which is updated monthly.2

The Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (RPBS) was implemented prior to the

PBS, in 1919.17 Veterans of the first World War and Boer War were eligible for benefits

and could receive free of charge most medicines available in Australia at the time.17 The

format of the RPBS remained largely unchanged until 1983, when benefits were restricted

to medicines available on the PBS plus an extra list of medicines specific to the needs of

veterans.17 Initially only six medicines were included on this "extra" list;17 however the

RPBS has now grown to include over 150 medicines.2

All Australian citizens and permanent residents, as well as visitors from countries with

which Australia has a reciprocal healthcare agreement (namely the United Kingdom, New

Zealand, Finland, Ireland, Italy, Malta, the Netherlands and Sweden) are eligible to receive

a The current Schedule of Pharmaceutical Benefits can be accessed on the internet from:

http://www.pbs.gov.au/html/healthpro/publication/list (last accessed January 17th 2008)

6

medicines subsidised on the PBS.2 RPBS medicines are limited to eligible Department of

Veterans' Affairs (DVA) treatment card holders, who include Australian defence force

veterans and eligible dependants such as widows or widowers. Patients eligible to receive

RPBS medicines can also receive all PBS subsidised medicines.22

There are two benefit categories for medicines subsidy on the PBS - general beneficiaries

and concession beneficiaries. Concession beneficiaries are those people who hold a

government Pension Concession Card, a Commonwealth Seniors Health card, a

government issued Health Care Card or a DVA treatment card.2 General beneficiaries are

all other patients eligible to receive PBS medicines.2 Co-payments differ for general

patients and concession patients. In 2008, concession patients paid $5.00 per PBS

prescription; the general co-payment was up to $31.30 for each PBS prescription, with the

remainder of the cost subsidised by the Australian government.23

2.1.2 Quality, safety and efficacy of medicines

The second objective of Australia’s National Medicines Policy aims to ensure that

medicines manufactured and supplied in Australia are of high quality, safety and efficacy.

This objective is supported by the legislative framework of the Therapeutic Goods Act

1989; which is administered by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA).18,24,25 All

therapeutic goods must be registered or listed on the Australian Register of Therapeutic

Goods (ARTG) before they can be sold in Australia.24,25 Therapeutic goods manufactured

solely for export from Australia must also be included in the ARTG. A therapeutic good is

defined as:

− “a product for use in humans that is used in, or in connection with:

− preventing, diagnosing, curing or alleviating a disease, ailment, deficit or

injury; or,

− influencing, inhibiting or modifying a physiological process; or,

− testing the susceptibility of persons to a disease or ailment; or,

− testing for pregnancy; or

− the replacement or modification of parts of the anatomy.”24

Therapeutic goods may be listed or registered on the ARTG depending on the ingredients

included in the product, its dosage form, and the claims made by the manufacturer

regarding the therapeutic efficacy of the product.24 Listed medicines are considered to be

“low risk” products; most commonly they are the types of medicines patients select for

7

themselves without requiring the input of a health professional, e.g. vitamins.24 The safety

and quality of listed products is assessed by TGA before they can be supplied in

Australia.24 Efficacy of listed medicines is not assessed by TGA; however, it is a legal

requirement that proof of efficacy can be provided if it is requested.24 Listed medicines are

available without a prescription and can be differentiated from registered medicines by an

“AUST L” number on the product label.24

Registered therapeutic goods are generally considered to be higher risk products than listed

medicines.24 They are the types of products which tend to have, or require, some level of

health professional involvement in their sale or use, e.g. medicines sold over the counter in

a pharmacy and prescription only medicines.24 There are two types of registered

medicines: low risk registered products are non-prescription medicines which are available

in a pharmacy and which may require advice from a pharmacist for use, e.g. oral

decongestants and over the counter pain relievers.24 High risk registered products are

available only on prescription.24 Registered medicines can be distinguished from listed

medicines by an “AUST R” number on the product label.24

There is a well defined process for the listing and registration of therapeutic goods in

Australia, which helps to ensure the quality and safety of products. The processes vary

slightly for listed medicines, and low and high risk registered medicines; however, the

fundamental principles involved are similar.24 The process begins with the sponsor of a

medicine (the manufacturer or importer) submitting an application to TGA.24 For listed

medicines, the application must contain information relating to the quality and safety of the

product. The application is assessed by the ARTG section of the TGA to determine

whether ingredients in the product are suitable for listing. If the listing application is

successful, the sponsor will be issued with an AUST L number for the product.24

The process for registration of products is slightly more complicated, and a number of

different departments within TGA are involved. Sponsors who wish to register a non-

prescription (low-risk) medicine submit their application to the Chemicals and Non-

prescription Medicine branch of TGA.24 The application must include evidence of the

quality, safety and efficacy of the product. Depending on whether the application is for a

conventional non-prescription medicine or a complementary medicine, the application is

forwarded to the OTC Medicines Evaluation Section or the Office of Complementary

Medicines of TGA.24 If the application is for a new product, it will also be reviewed by a

relevant expert committee (the TGA Medicines Evaluation Committee or the

Complementary Medicines Evaluation Committee). A report is then given to TGA which

8

reviews the application and expert committee evaluation, and makes a final decision on

whether to approve the registration application.24

Applications for the registration of prescription (high-risk) medicines include detailed

information on the chemistry, safety, clinical effects and indication(s), adverse effects, and

pharmacokinetics of the medicine.26 These applications are submitted to the Drug Safety

and Evaluation Branch of TGA, which reviews the application and seeks advice from

external expert committees if necessary.24 Recommendations from these committees are

then submitted to the Australian Drug Evaluation Committee (ADEC), which provides a

final review of the application and makes a recommendation regarding whether the

application should be approved or rejected. ADEC membership includes medical

practitioners, pharmacologists, toxicologists and a manufacturing pharmaceutical

chemist.26 The Drug Safety Evaluation Branch of TGA considers the recommendation

from ADEC and makes the final decision on whether the medicine should be given

registration approval.24 This formal process helps to ensure the quality and safety of all

therapeutic goods available in Australia.

Safety of medicines following marketing approval in Australia is monitored by the

Adverse Drug Reactions Advisory Committee (ADRAC), a sub-committee of ADEC.18,26

Health care professionals and members of the public may report suspected adverse drug

reactions to ADRAC and drug companies are required by law to provide this information.

ADRAC maintains a register of these reports and produces a summary of results in a bi-

monthly bulletin for health professionals.26,27 If new information becomes available after

the listing or registration of a medicine such that TGA has serious concerns regarding the

quality or safety of the medicine, then licensing or regulatory approval may be withdrawn.

In addition to the process for registration of medicines, the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989

requires pharmaceutical manufacturers to be licensed to produce medicines for human

use.24 Licensed manufacturers must adhere to the “Australian Code of Good

Manufacturing Practice for Medicinal Products” which outlines the manufacturing

requirements to ensure the quality and safety of medicines manufactured in Australia.24,28

The aim of licensing of manufacturers is to ensure that medicines manufactured in

Australia meet high and specified quality standards.24 Manufacturers are audited by TGA

to ensure that their premises and manufacturing processes meet these standards.

9

2.1.3 Quality use of medicines

The third arm of Australia’s National Medicines Policy aims to ensure the quality use of

medicines. The conceptual framework used to achieve this is described in detail in the

National Strategy for Quality Use of Medicines.19 The overall goal of the National Strategy

for Quality Use of Medicines is “to optimise the use of medicines to improve health

outcomes for all Australians.”19 Quality use of medicines (QUM) is defined as:

−

“Judicious selection of management options. This means consideration of

the place of medicines in treating illness and maintaining health,

recognising that for the management of many disorders non-drug therapies

may be the best option;

−

Appropriate choice of medicines, where a medicine is considered

necessary. This means that, when medicines are required, selecting the best

option from the range available taking into account the individual, the

clinical condition, risks, benefits, dosage, length of treatment, co-

morbidities, other therapies and monitoring considerations. Appropriate

selection also requires a consideration of costs, both human and economic.

These costs should be considered both for the individual, the community

and the health system as a whole;

and

−

Safe and effective use. This means ensuring best possible outcomes of

therapy by monitoring outcomes, minimising misuse, over-use and under-

use, as well as improving the ability of all individuals to take appropriate

actions to solve medication-related problems, eg, adverse effects and

managing multiple medications.”19

One of the central principles involved in achieving QUM is partnership between all of the

stakeholders, who include consumers; health care providers, practitioners and educators;

the pharmaceutical industry; media and the government.19 In addition, the National

Strategy for QUM outlines six building blocks which have been shown to be integral in

supporting and achieving QUM:

•

“policy development and implementation;

•

facilitation and coordination of QUM initiatives;

•

provision of objective information and assurance of ethical promotion of medicines;

•

education and training;

•

provision of services and appropriate interventions; and

•

strategic research, evaluation and routine data collection.”19

The Pharmaceutical Health and Rational Use of Medicines (PHARM) committee is

responsible for overseeing the implementation and evaluation of the National Strategy for

Quality Use of Medicines.19 PHARM is an expert advisory committee with members

10

drawn from fields including medical practitioners, pharmacists, the pharmaceutical

industry, consumers, health educators and behavioural science.19

The National Prescribing Service (NPS) is a government funded, independent, non-profit

organisation which supports QUM by providing prescribing advice and implementing

programmes and guidelines to support rational and quality prescribing.29 A number of

QUM interventions are implemented by NPS, including academic detailing, prescriber self

audits, provision of case studies and continuing education meetings.29 The topics covered

in the interventions are chosen in response to criteria including General Practitioner (GP)

requests for education, where variability in the quality of prescribing in a certain area has

been identified, or when new prescribing guidelines are implemented.29 In addition to

providing services to prescribers, NPS also offers services for other health professionals

and for consumers.

2.1.4 A responsible and viable medicines industry in Australia

The fourth objective of the National Medicines Policy, maintaining a responsible and

viable medicines industry in Australia, began with the Factor f scheme in 1988.1 During

the 1980s activity of the pharmaceutical industry in Australia was declining. One of the

main factors noted to contribute to this decline was the low prices paid to pharmaceutical

companies for many PBS subsidised medicines compared to the prices paid for the same

medicines elsewhere in the world.1 There was a perception amongst the pharmaceutical

industry that Australia was a “hostile environment” for pharmaceutical manufacturing and

investment.1 The Factor f scheme was introduced in 1988 to try and reverse the trend of

declining pharmaceutical manufacture, research and development in Australia.1

Under the Factor f scheme, participating companies were able to receive higher prices for

some of their PBS listed medicines.1 In return, these companies had to increase their rate of

pharmaceutical export from Australia and increase their investment in pharmaceutical

research and development in Australia.1 Two phases of the scheme operated: Phase I

operated from 1988 to 1995; phase II overlapped with phase I, beginning in 1992 and

ending in 1999.1 Participation in phase I was based on a company’s ability to meet

eligibility criteria, including increasing pharmaceutical export and research and

development in Australia to levels predetermined by the government.1 All of the

companies who met these criteria were eligible to participate in phase I of the scheme.1

Similar criteria were used to determine eligibility for participation in phase II of the Factor

f scheme; however, companies also had to submit an application regarding their proposed

11

activity to increase pharmaceutical manufacturing and research and development in

Australia.1 Funding for phase II of the scheme was capped at $820 million and as a result a

number of pharmaceutical companies who met the eligibility criteria were unable to

participate, because the available funds had already been allocated.1

The Pharmaceutical Industry Investment Program (PIIP) replaced the Factor f scheme in

1999.30 Like the Factor f scheme, under PIIP pharmaceutical companies were able to

receive higher prices for some of their PBS subsidised medicines if they could prove that

the prices paid for these medicines under the PBS were lower than the prices paid for the

same medicines in the European Union.30 In return, these companies were required to

increase their pharmaceutical manufacturing and research and development in Australia.

Unlike the Factor f scheme, participation in PIIP was competitive. Pharmaceutical

companies were required to submit an application outlining their proposed increases to

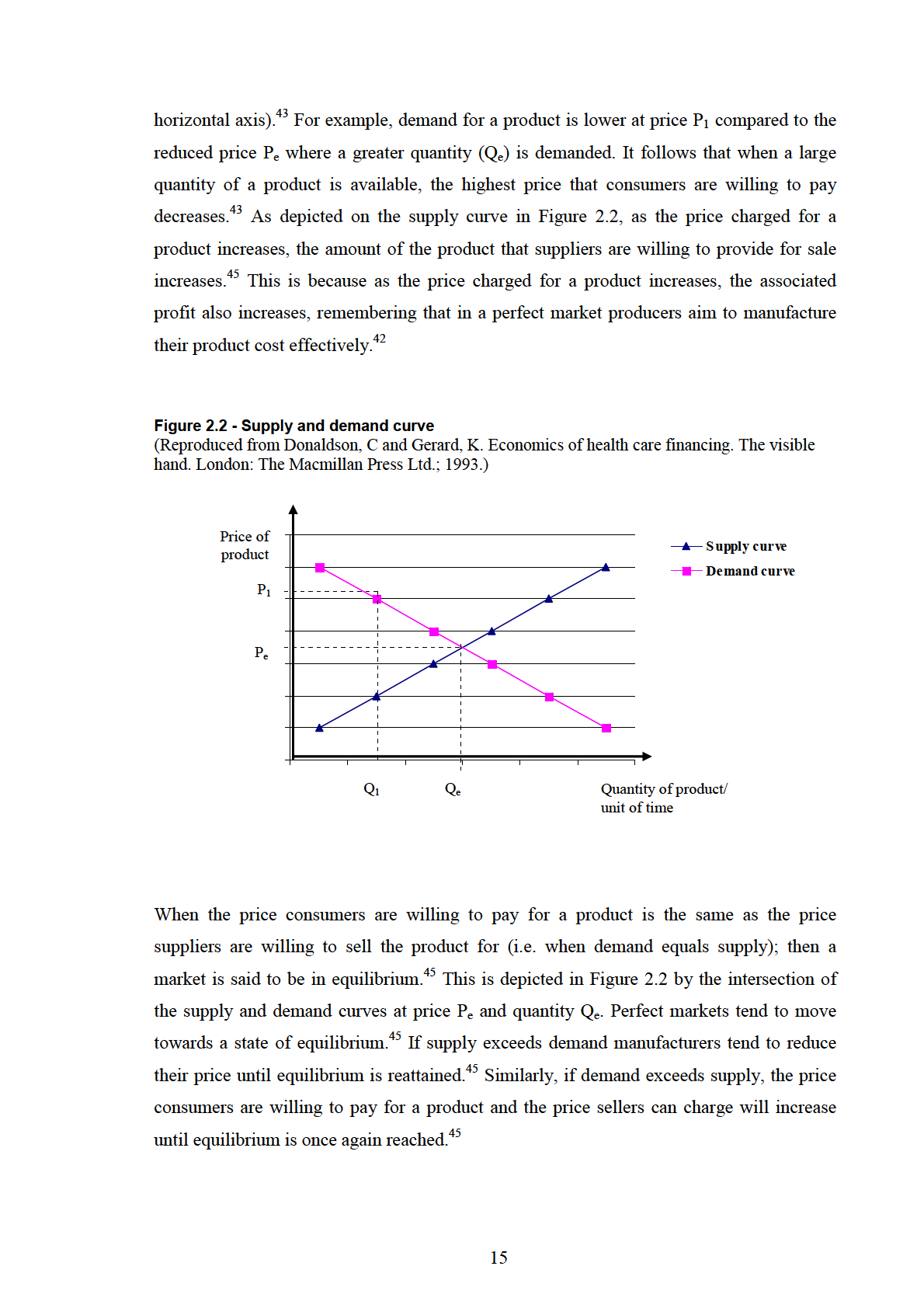

pharmaceutical manufacturing and research and development activity in Australia.30