Document 1 - Page 1 of 2

s 22(1)

From: s 22(1)

@pmc.gov.au]

Sent: Monday, 29 May 2017 11:16 AM

To: s 22(1)

Cc: s 22(1)

Subject: FW: QB16-000513 [DLM=For-Official-Use-Only]

For Official Use Only

Good morning s 22(1)

Apologies for the delay getting this to you. Attached is our QTB, which includes a copy of the

Uluru Statement from the Heart.

If any changes are made in the MO, I will let you know. Also very happy to discuss further.

Thanks

s 22(1)

s 22(1)

l Senior Adviser

Constitutional Recognition Taskforce

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet | Indigenous Affairs

s 22(1)

s 22(1)

@pmc.gov.au | www.dpmc.gov.au | www.indigenous.gov.au

PO Box 6500 CANBERRA ACT 2600

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet acknowledges the traditional owners of country throughout Australia

and their continuing connection to land, sea and community. We pay our respect to them and their cultures, and to the

elders both past and present.

______________________________________________________________________

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 1 of 211

Document 1 - Page 2 of 2

IMPORTANT: This message, and any attachments to it, contains information

that is confidential and may also be the subject of legal professional or

other privilege. If you are not the intended recipient of this message, you

must not review, copy, disseminate or disclose its contents to any other

party or take action in reliance of any material contained within it. If you

have received this message in error, please notify the sender immediately by

return email informing them of the mistake and delete all copies of the

message from your computer system.

______________________________________________________________________

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 2 of 211

Document 2 - Page 1 of 11

IN

CONFIDENCE

*

PDR: QB16-000513

QUESTION TIME BRIEF (QTB)

INDIGENOUS – CONSTITUTIONAL RECOGNITION

QUESTION: What is the Government doing to progress constitutional recognition?

KEY POINTS:

The Government is committed to the recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Formatted: Font: 14 pt

Islander people and we have worked in partnership with Indigenous Australians to

Formatted: Don't add space between paragraphs of the

same style, Don't allow hanging punctuation, Don't adjust

hear the views of communities across the country.

space between Latin and Asian text, Don't adjust space

between Asian text and numbers, Font Alignment: Baseline

Formatted: List Paragraph, Indent: Left: 0.63 cm, First line:

On 7 December 2015, the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition

0 cm

created a Referendum Council to provide advice to Parliament on the next steps

Formatted: Don't add space between paragraphs of the

towards a successful referendum, including timing of a referendum and a possible

same style, Don't allow hanging punctuation, Don't adjust

space between Latin and Asian text, Don't adjust space

model.

between Asian text and numbers, Font Alignment: Baseline

Formatted: List Paragraph, Indent: Left: 0.63 cm, First line:

0 cm

We thank the National Constitutional Convention delegates for their work which

Formatted: Don't add space between paragraphs of the

will now be considered by the Referendum Council. The Council will, in turn,

same style, Don't allow hanging punctuation, Don't adjust

advise the Prime Minister and Leader of the Opposition and through them, the

space between Latin and Asian text, Don't adjust space

between Asian text and numbers, Font Alignment: Baseline

Parliament.

Formatted: List Paragraph, Indent: Left: 0.63 cm, First line:

s 22(1)

0 cm

Formatted: Don't add space between paragraphs of the

same style, Don't allow hanging punctuation, Don't adjust

space between Latin and Asian text, Don't adjust space

between Asian text and numbers, Font Alignment: Baseline

Formatted: Font: 14 pt

Formatted: List Paragraph, Indent: Left: 0.63 cm, First line:

0 cm

Formatted: Don't add space between paragraphs of the

same style, Don't allow hanging punctuation, Don't adjust

space between Latin and Asian text, Don't adjust space

between Asian text and numbers, Font Alignment: Baseline

Formatted: Indent: Left: 0.63 cm

Formatted: Don't add space between paragraphs of the

same style, Don't allow hanging punctuation, Don't adjust

space between Latin and Asian text, Don't adjust space

between Asian text and numbers, Font Alignment: Baseline

The Government is committed to the recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Formatted: List Paragraph, Indent: Left: 0.63 cm, First line:

0 cm

Islander peoples in our Constitution.

Formatted: Don't add space between paragraphs of the

same style, Don't allow hanging punctuation, Don't adjust

On 7 December 2015, the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition created a

space between Latin and Asian text, Don't adjust space

between Asian text and numbers, Font Alignment: Baseline

Referendum Council to provide advice on the next steps towards a successful referendum, including

Formatted: Normal, Indent: Left: 0.63 cm, No bullets or

timing of a referendum and a possible model.

numbering

Formatted: Normal, No bullets or numbering

The Council has completed 12 First Nations Regional Dialogues, and an Information Day.

Formatted: Normal, Indent: Left: 0 cm

The Indigenous consultation process culminates in a National Constitutional Convention taking

Formatted: Normal, No bullets or numbering

place this week at Uluru. The Council also sought the views of the broader community through a

written submission process, digital consultations and targeted stakeholder engagement.

Formatted: Normal

CONTACT: s 22(1)

DIVISION: IER DATE:

294 MAY 2017 DEPARTMENTAL INPUT CLEARED BY: Gayle Anderson

*Not for tabling – For Official Use Only

1

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 3 of 211

Document 2 - Page 4 of 11

IN

CONFIDENCE

*

PDR: QB16-000513

s 22(1)

The National Convention is being held at Uluru on 23-26 May 2017.

The National Constitutional Convention was held at Uluru on 23-26 May 2017.

Delegates agreed the ‘Uluru Statement from the Heart’, which:

asserts continuing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander sovereignty, which co-

Formatted: List Paragraph, Bulleted + Level: 1 + Aligned at:

0 cm + Indent at: 0.63 cm

exists with the sovereignty of the Crown;

seeks the establishment of a constitutionally-enshrined First Nations Voice in the

Parliament; and

calls for the establishment of a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of

agreement-making between governments and First Nations and truth-telling.

A copy of the Statement is at Attachment B.

Formatted: Font: 14 pt

s 22(1)

CONTACT: s 22(1)

DIVISION: IER DATE:

294 MAY 2017 DEPARTMENTAL INPUT CLEARED BY: Gayle Anderson

*Not for tabling – For Official Use Only

4

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 4 of 211

Document 2 - Page 9 of 11

IN

CONFIDENCE

*

PDR: QB16-000513

Attachment B

Formatted: Font: Bold

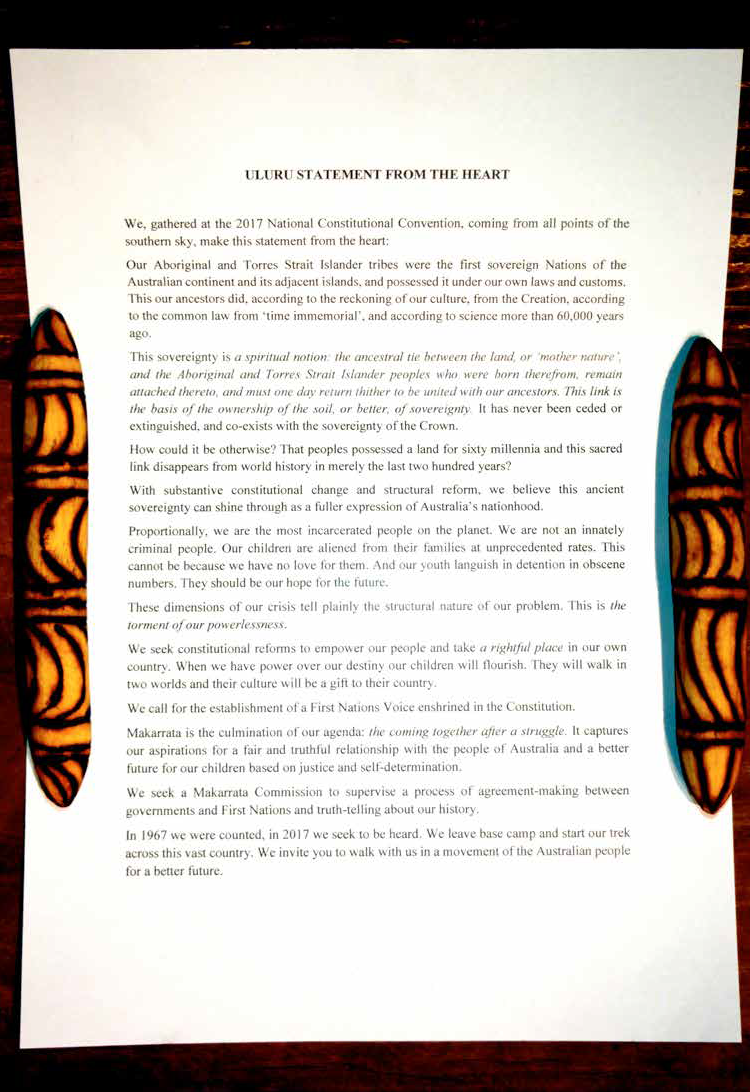

ULURU STATEMENT FROM THE HEART

Formatted: Right

We, gathered at the 2017 National Constitutional Convention, coming from all points of the

southern sky, make this statement from the heart:

Our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes were the first sovereign Nations of the Australian

continent and its adjacent islands, and possessed it under our own laws and customs. This our

ancestors did, according to the reckoning of our culture, from the Creation, according to the

common law from ‘time immemorial’, and according to science more than 60,000 years ago.

This sovereignty is

a spiritual notion: the ancestral tie between the land, or ‘mother nature’, and

the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were born therefrom, remain attached

thereto, and must one day return thither to be united with our ancestors. This link is the basis of the

ownership of the soil, or better, of sovereignty. It has never been ceded or extinguished, and co-

exists with the sovereignty of the Crown.

How could it be otherwise? That peoples possessed a land for sixty millennia and this sacred link

disappears from world history in merely the last two hundred years?

With substantive constitutional change and structural reform, we believe this ancient sovereignty

can shine through as a fuller expression of Australia’s nationhood.

Proportionally, we are the most incarcerated people on the planet. We are not an innately criminal

people. Our children are aliened from their families at unprecedented rates. This cannot be because

we have no love for them. And our youth languish in detention in obscene numbers. They should be

our hope for the future.

These dimensions of our crisis tell plainly the structural nature of our problem. This is

the torment

of our powerlessness.

We seek constitutional reforms to empower our people and take

a rightful place in our own country.

When we have power over our destiny our children will flourish. They will walk in two worlds and

their culture will be a gift to their country.

We call for the establishment of a First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution.

Makarrata is the culmination of our agenda:

the coming together after a struggle. It captures our

aspirations for a fair and truthful relationship with the people of Australia and a better future for our

children based on justice and self-determination.

We seek a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making between

governments and First Nations and truth-telling about our history.

In 1967 we were counted, in 2017 we seek to be heard. We leave base camp and start our trek

across this vast country. We invite you to walk with us in a movement of the Australian people for a

better future

CONTACT: s 22(1)

DIVISION: IER DATE:

294 MAY 2017 DEPARTMENTAL INPUT CLEARED BY: Gayle Anderson

*Not for tabling – For Official Use Only

9

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 5 of 211

Document 3 - Page 1 of 4

From:

s 22(1)

To:

s 22(1)

Cc:

Lewis, David; s 22(1)

; Virtue, Joanna; s 22(1)

; Anderson, Gayle

Subject:

s 47C(1)

[SEC=PROTECTED]

Date:

Thursday, 8 June 2017 6:51:25 PM

Attachments:

s 47C(1)

PROTECTED

No problem – many thanks to you too for your patience. For reference, I’ve attached final

agreed drafts.

Thanks

s 22(1)

Principal Legal Officer

Office of Constitutional Law

Attorney-General’s Department

s 22(1)

@ag.gov.au

From: s 22(1)

@pmc.gov.au]

Sent: Thursday, 8 June 2017 6:40 PM

To: s 22(1)

Cc: Lewis, David; s 22(1)

; Virtue, Joanna; s 22(1)

; Anderson, Gayle

Subject: s 47C(1)

[SEC=PROTECTED]

PROTECTED

Thanks so much s 22(1) – really appreciate everything today!

I will be in touch tomorrow – with any feedback from our Office and the s 47C(1)

.

Thanks again

s 22(1)

From: s 22(1)

@ag.gov.au]

Sent: Thursday, 8 June 2017 6:39 PM

To: s 22(1)

@pmc.gov.au>

Cc: Lewis, David s 22(1)

@ag.gov.au>; s 22(1)

@ag.gov.au>; Virtue, Joanna s 22(1)

@pmc.gov.au>; s 22(1)

@pmc.gov.au>; Anderson, Gayle s 22(1)

@pmc.gov.au>

Subject: s 47C(1)

[SEC=PROTECTED]

PROTECTED

Hi s 22(1) – this has now been cleared by our deputy secretary. We will send it to the AGO now.

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 6 of 211

Document 3 - Page 2 of 4

Thanks

s 22(1)

Principal Legal Officer

Office of Constitutional Law

Attorney-General’s Department

s 22(1)

@ag.gov.au

From: s 22(1)

@pmc.gov.au]

Sent: Thursday, 8 June 2017 6:10 PM

To: s 22(1)

Cc: Lewis, David; s 22(1)

; Virtue, Joanna; s 22(1)

Anderson, Gayle

Subject: s 47C(1)

[SEC=PROTECTED]

PROTECTED

Thanks s 22(1) – happy with that small change.

From: s 22(1)

@ag.gov.au]

Sent: Thursday, 8 June 2017 6:06 PM

To: s 22(1)

@pmc.gov.au>

Cc: Lewis, David s 22(1)

@ag.gov.au>; s 22(1)

@ag.gov.au>; Virtue, Joanna s 22(1)

@pmc.gov.au>; s 22(1)

@pmc.gov.au>; Anderson, Gayle s 22(1)

@pmc.gov.au>

Subject: s 47C(1)

[SEC=PROTECTED]

Importance: High

PROTECTED

Hi s 22(1)

We think this should be OK with one small change as marked. We’ll clear this with our Dep Sec

now as quickly as possible.

Thanks

s 22(1)

Principal Legal Officer

Office of Constitutional Law

Attorney-General’s Department

s 22(1)

@ag.gov.au

From: s 22(1)

@pmc.gov.au]

Sent: Thursday, 8 June 2017 5:58 PM

To: s 22(1)

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 7 of 211

Document 3 - Page 3 of 4

Cc: Lewis, David; s 22(1)

; Virtue, Joanna; s 22(1)

; Anderson, Gayle

Subject: s 47C(1)

[SEC=PROTECTED]

Importance: High

PROTECTED

Hi s 22(1)

Following our conversation, I have s 47C(1)

– can you let me know if you

are happy to proceed on this basis?

Separately, our MO are looking to have the paper by 6pm – do you have an ETA on when your

Secretary is likely to clear?

Apologies and thanks so much

s 22(1)

______________________________________________________________________

IMPORTANT: This message, and any attachments to it, contains information

that is confidential and may also be the subject of legal professional or

other privilege. If you are not the intended recipient of this message, you

must not review, copy, disseminate or disclose its contents to any other

party or take action in reliance of any material contained within it. If you

have received this message in error, please notify the sender immediately by

return email informing them of the mistake and delete all copies of the

message from your computer system.

______________________________________________________________________

If you have received this transmission in error please

notify us immediately by return e-mail and delete all

copies. If this e-mail or any attachments have been sent

to you in error, that error does not constitute waiver

of any confidentiality, privilege or copyright in respect

of information in the e-mail or attachments.

______________________________________________________________________

IMPORTANT: This message, and any attachments to it, contains information

that is confidential and may also be the subject of legal professional or

other privilege. If you are not the intended recipient of this message, you

must not review, copy, disseminate or disclose its contents to any other

party or take action in reliance of any material contained within it. If you

have received this message in error, please notify the sender immediately by

return email informing them of the mistake and delete all copies of the

message from your computer system.

______________________________________________________________________

If you have received this transmission in error please

notify us immediately by return e-mail and delete all

copies. If this e-mail or any attachments have been sent

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 8 of 211

Document 3 - Page 4 of 4

to you in error, that error does not constitute waiver

of any confidentiality, privilege or copyright in respect

of information in the e-mail or attachments.

______________________________________________________________________

IMPORTANT: This message, and any attachments to it, contains information

that is confidential and may also be the subject of legal professional or

other privilege. If you are not the intended recipient of this message, you

must not review, copy, disseminate or disclose its contents to any other

party or take action in reliance of any material contained within it. If you

have received this message in error, please notify the sender immediately by

return email informing them of the mistake and delete all copies of the

message from your computer system.

______________________________________________________________________

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 9 of 211

Document 5 - Page 1 of 1

ATTACHMENT A

ULURU STATEMENT FROM THE HEART

We, gathered at the 2017 National Constitutional Convention, coming from all points of the

southern sky, make this statement from the heart:

Our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes were the first sovereign Nations of the

Australian continent and its adjacent islands, and possessed it under our own laws and

customs. This our ancestors did, according to the reckoning of our culture, from the Creation,

according to the common law from ‘time immemorial’, and according to science more than

60,000 years ago.

This sovereignty is

a spiritual notion: the ancestral tie between the land, or ‘mother nature’,

and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were born therefrom, remain

attached thereto, and must one day return thither to be united with our ancestors. This link is

the basis of the ownership of the soil, or better, of sovereignty. It has never been ceded or

extinguished, and co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown.

How could it be otherwise? That peoples possessed a land for sixty millennia and this sacred

link disappears from world history in merely the last two hundred years?

With substantive constitutional change and structural reform, we believe this ancient

sovereignty can shine through as a fuller expression of Australia’s nationhood.

Proportionally, we are the most incarcerated people on the planet. We are not an innately

criminal people. Our children are aliened from their families at unprecedented rates. This

cannot be because we have no love for them. And our youth languish in detention in obscene

numbers. They should be our hope for the future.

These dimensions of our crisis tell plainly the structural nature of our problem. This is

the

torment of our powerlessness.

We seek constitutional reforms to empower our people and take

a rightful place in our own

country. When we have power over our destiny our children will flourish. They will walk in

two worlds and their culture will be a gift to their country.

We call for the establishment of a First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution.

Makarrata is the culmination of our agenda:

the coming together after a struggle. It captures

our aspirations for a fair and truthful relationship with the people of Australia and a better

future for our children based on justice and self-determination.

We seek a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making between

governments and First Nations and truth-telling about our history.

In 1967 we were counted, in 2017 we seek to be heard. We leave base camp and start our trek

across this vast country. We invite you to walk with us in a movement of the Australian

people for a better future.

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 10 of 211

Document 7 - Page 1 of 1

From:

s 22(1)

To:

s 22(1)

Cc:

; Lewis, David; Anderson, Gayle; Virtue, Joanna; s 22(1)

Subject:

s 47C(1)

[SEC=PROTECTED, DLM=Sensitive:Cabinet]

Date:

Friday, 9 June 2017 4:46:16 PM

Attachments:

s 47C(1)

PROTECTED Sensitive: Cabinet

Hi s 22(1)

Many thanks for your work clearing the revised paper. Please find attached finals, taking into

account all our changes – we will now provide to the MO.

s 22(1)

l Senior Adviser

Constitutional Recognition Taskforce

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet | Indigenous Affairs

s 22(1)

s 22(1)

@pmc.gov.au | www.dpmc.gov.au | www.indigenous.gov.au

PO Box 6500 CANBERRA ACT 2600

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet acknowledges the traditional owners of country throughout Australia

and their continuing connection to land, sea and community. We pay our respect to them and their cultures, and to the

elders both past and present.

______________________________________________________________________

IMPORTANT: This message, and any attachments to it, contains information

that is confidential and may also be the subject of legal professional or

other privilege. If you are not the intended recipient of this message, you

must not review, copy, disseminate or disclose its contents to any other

party or take action in reliance of any material contained within it. If you

have received this message in error, please notify the sender immediately by

return email informing them of the mistake and delete all copies of the

message from your computer system.

______________________________________________________________________

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 11 of 211

Document 10 - Page 1 of 2

ATTACHMENT C

TALKING POINTS

• The Coalition Government remains committed to the recognition of Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander people in the Constitution.

• The Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition appointed the Referendum

Council to provide advice to Parliament on the next steps towards a successful

referendum, including timing of a referendum and a possible model.

• We thank the delegates at Uluru for their work which wil now be considered by

the Referendum Council which wil in turn advise the Prime Minister and

Opposition Leader and through them, the Parliament.

s 22(1)

If asked – about the Government position on constitutional recognition

s 22(1)

• The work of the Uluru delegates is currently being considered by the Referendum

Council in developing its Final Report to the Prime Minister and Opposition

Leader.

If asked - about specific models for recognition including treaty and an Indigenous

voice in Parliament

• As a key part of the Uluru statement I expect the Referendum Council wil cover

this issue in its Final Report. We need to wait and consider any recommendations

of the Referendum Council in its Final Report which wil be presented to the

Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition soon by 30 June 2017.

• These matters are very important and they deserve very serious consideration.

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 12 of 211

Document 11 - Page 1 of 1

From:

s 22(1)

To:

s 22(1)

Cc:

Lewis, David; Anderson, Gayle; Virtue, Joanna; s 22(1)

Subject:

s 47C(1)

[SEC=PROTECTED, DLM=Sensitive:Cabinet]

Date:

Wednesday, 14 June 2017 4:26:53 PM

Attachments:

s 47C(1)

PROTECTED Sensitive: Cabinet

Hi s 22(1)

Please find attached the s 47C(1)

.

We will now send to the MO and PMO, seeking their confirmation that the papers can now be

lodged with s 47C(1) – if you could seek the same confirmation from AGO that would be fantastic.

We will let you know if there are any further developments – I understand the s 47C(1)

is

now calling all the MOs to lodge the paper asap.

Thanks again for all your assistance

s 22(1)

l Senior Adviser

Constitutional Recognition Taskforce

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet | Indigenous Affairs

s 22(1)

s 22(1)

@pmc.gov.au | www.dpmc.gov.au | www.indigenous.gov.au

PO Box 6500 CANBERRA ACT 2600

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet acknowledges the traditional owners of country throughout Australia

and their continuing connection to land, sea and community. We pay our respect to them and their cultures, and to the

elders both past and present.

______________________________________________________________________

IMPORTANT: This message, and any attachments to it, contains information

that is confidential and may also be the subject of legal professional or

other privilege. If you are not the intended recipient of this message, you

must not review, copy, disseminate or disclose its contents to any other

party or take action in reliance of any material contained within it. If you

have received this message in error, please notify the sender immediately by

return email informing them of the mistake and delete all copies of the

message from your computer system.

______________________________________________________________________

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 13 of 211

Document 13 - Page 1 of 2

ATTACHMENT C

TALKING POINTS

• The Coalition Government remains committed to the recognition of Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander people in the Constitution.

• The Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition appointed the Referendum

Council to provide advice to Parliament on the next steps towards a successful

referendum, including timing of a referendum and a possible model.

• We thank the delegates at Uluru for their work which wil now be considered by

the Referendum Council which wil in turn advise the Prime Minister and

Opposition Leader and through them, the Parliament.

s 22(1)

If asked – about the Government position on constitutional recognition • The work of the Uluru delegates is currently being considered by the Referendum

Council in developing its Final Report to the Prime Minister and Opposition

Leader.

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 14 of 211

Document 13 - Page 2 of 2

If asked - about specific models for recognition including treaty and an Indigenous

voice in Parliament

• As a key part of the Uluru statement I expect the Referendum Council wil cover

this issue in its Final Report. We need to wait and consider any recommendations

of the Referendum Council in its Final Report which wil be presented to the

Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition soon by 30 June 2017.

• These matters are very important and they deserve very serious consideration.

s 22(1)

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 15 of 211

Document 15 - Page 1 of 3

From:

To:

s 22(1)

Cc:

s 22(1)

; Virtue, Joanna; s 22(1)

; Lewis, David

Subject:

s 47C(1)

[SEC=PROTECTED, DLM=Sensitive:Cabinet]

Date:

Wednesday, 14 June 2017 4:00:42 PM

Attachments:

s 47C(1)

PROTECTED Sensitive: Cabinet

Hi s 22(1)

,

Attached is an updated version of the attachments to the paper, including s 47C(1)

.

Please let us know when you’re happy for us to send this and the paper to the AGO.

Regards

_________________________________

s 22(1)

Senior Legal Officer

Office of Constitutional Law

Attorney-General’s Department

s 22(1)

@ag.gov.au

s 22(1)

From: s 22(1)

Sent: Wednesday, 14 June 2017 3:22 PM

To: s 22(1)

'

Cc: s 22(1)

; Virtue, Joanna; s 22(1)

Subject: s 47C(1)

[SEC=PROTECTED,

DLM=Sensitive:Cabinet]

PROTECTED Sensitive: Cabinet

Hi s 22(1)

Some brief comments are included in the attached documents, shown in mark-up. We’ve

highlighted our changes (and removed the highlighting that was previously in the two

documents, but otherwise left all tracked changes in place). s 47C(1)

.

Happy to discuss,

_________________________________

s 22(1)

Senior Legal Officer

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 16 of 211

Document 15 - Page 2 of 3

Office of Constitutional Law

Attorney-General’s Department

s 22(1)

@ag.gov.au

s 22(1)

From: s 22(1)

@pmc.gov.au]

Sent: Wednesday, 14 June 2017 1:02 PM

To: s 22(1)

Cc: s 22(1)

; Virtue, Joanna

Subject: s 47C(1)

[SEC=PROTECTED,

DLM=Sensitive:Cabinet]

PROTECTED Sensitive: Cabinet

Hi s 22(1)

I’m not having much luck catching you both today – feel free to call to discuss.

The attached paper has been cleared by our FAS so from our perspective is ready to go. The only

change with this paper from the one that s 22(1) sent to you earlier, is to s 47C(1)

.

Do you have an ETA on when you might be able to get the paper cleared? Once you have cleared

we need to get this to the MIAO and AGO as soon as we can because s 47C(1)

says

that it needs to go ASAP today – preferably by 2pm!

Thanks

s 22(1)

Adviser

nal Recognition Taskforce | Indigenous Employment and Recognition Division

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

p. s 22(1)

e. s 22(1)

@pmc.gov.au

www.dpmc.gov.au

GPO Box 6500 CANBERRA ACT 2600

s 22(1)

The Department acknowledges the traditional owners of country throughout Australia and their continuing

connection to land, sea and community. We pay our respects to them and their cultures and to their elders both

past and present.

From: s 22(1)

Sent: Wednesday, 14 June 2017 12:05 PM

To: s 22(1)

Cc: Virtue, Joanna; s 22(1)

; Lewis, David

Subject: s 47C(1)

[SEC=PROTECTED, DLM=Sensitive:Cabinet]

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 17 of 211

Document 15 - Page 3 of 3

Importance: High

PROTECTED Sensitive: Cabinet

Hi s 22(1)

Please find attached s 47C(1)

These are currently with Gayle for clearance, but wanted to provide them to you as well to

review. The PMO and MO have made further changes, and the attached is our feedback – would

appreciate your thoughts as well.

We are unclear what engagement the AGO has had at this stage.

Thanks so much

s 22(1)

l Senior Adviser

Constitutional Recognition Taskforce

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet | Indigenous Affairs

s 22(1)

s 22(1)

@pmc.gov.au | www.dpmc.gov.au | www.indigenous.gov.au

PO Box 6500 CANBERRA ACT 2600

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet acknowledges the traditional owners of country throughout Australia

and their continuing connection to land, sea and community. We pay our respect to them and their cultures, and to the

elders both past and present.

______________________________________________________________________

IMPORTANT: This message, and any attachments to it, contains information

that is confidential and may also be the subject of legal professional or

other privilege. If you are not the intended recipient of this message, you

must not review, copy, disseminate or disclose its contents to any other

party or take action in reliance of any material contained within it. If you

have received this message in error, please notify the sender immediately by

return email informing them of the mistake and delete all copies of the

message from your computer system.

______________________________________________________________________

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 18 of 211

Document 16 - Page 1 of 1

ATTACHMENT A

ULURU STATEMENT FROM THE HEART

We, gathered at the 2017 National Constitutional Convention, coming from all points of the

southern sky, make this statement from the heart:

Our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes were the first sovereign Nations of the

Australian continent and its adjacent islands, and possessed it under our own laws and

customs. This our ancestors did, according to the reckoning of our culture, from the Creation,

according to the common law from ‘time immemorial’, and according to science more than

60,000 years ago.

This sovereignty is

a spiritual notion: the ancestral tie between the land, or ‘mother nature’,

and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were born therefrom, remain

attached thereto, and must one day return thither to be united with our ancestors. This link is

the basis of the ownership of the soil, or better, of sovereignty. It has never been ceded or

extinguished, and co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown.

How could it be otherwise? That peoples possessed a land for sixty millennia and this sacred

link disappears from world history in merely the last two hundred years?

With substantive constitutional change and structural reform, we believe this ancient

sovereignty can shine through as a fuller expression of Australia’s nationhood.

Proportionally, we are the most incarcerated people on the planet. We are not an innately

criminal people. Our children are aliened from their families at unprecedented rates. This

cannot be because we have no love for them. And our youth languish in detention in obscene

numbers. They should be our hope for the future.

These dimensions of our crisis tell plainly the structural nature of our problem. This is

the

torment of our powerlessness.

We seek constitutional reforms to empower our people and take

a rightful place in our own

country. When we have power over our destiny our children will flourish. They will walk in

two worlds and their culture will be a gift to their country.

We call for the establishment of a First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution.

Makarrata is the culmination of our agenda:

the coming together after a struggle. It captures

our aspirations for a fair and truthful relationship with the people of Australia and a better

future for our children based on justice and self-determination.

We seek a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making between

governments and First Nations and truth-telling about our history.

In 1967 we were counted, in 2017 we seek to be heard. We leave base camp and start our trek

across this vast country. We invite you to walk with us in a movement of the Australian

people for a better future.

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 19 of 211

Document 18 - Page 1 of 3

ATTACHMENT C

TALKING POINTS

s 22(1)

The Coalition Government remains committed to the recognition of Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander people in the Constitution.

The Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition appointed the Referendum

Council to provide advice to Parliament on the next steps towards a successful

referendum, including timing of a referendum and a possible model.

We thank the delegates at Uluru for their work which will now be considered by

the Referendum Council which will in turn advise the Prime Minister and

Opposition Leader and through them, the Parliament.

s 22(1)

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 20 of 211

Document 18 - Page 2 of 3

The work of the Uluru delegates is currently being considered by the Referendum

Council in developing its Final Report to the Prime Minister and Opposition

Leader.

If asked - about specific models for recognition including treaty and an Indigenous

voice in Parliament

As a key part of the Uluru statement I expect the Referendum Council will cover

this issue in its Final Report. We need to wait and consider any recommendations

of the Referendum Council in its Final Report which will be presented to the

Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition soon by 30 June 2017.

These matters are very important and they deserve very serious consideration.

s 22(1)

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 21 of 211

Document 19 - Page 1 of 1

From:

s 22(1)

To:

s 22(1)

Cc:

Lewis, David; Virtue, Joanna; s 22(1)

; Anderson, Gayle

Subject:

s 47C(1)

[SEC=PROTECTED, DLM=Sensitive:Cabinet]

Date:

Thursday, 15 June 2017 10:34:35 AM

Attachments:

s 47C(1)

PROTECTED Sensitive: Cabinet

Hi s 22(1)

As discussed, please find attached thes 47C(1)

We received these back from our MO this morning, cleared by the Minister for lodgement with

the s 47C(1)

.

The advice from our MO was also that they would check this version with AGO, to ensure they

are comfortable. We are waiting for this confirmation before lodging the documents – will keep

you posted when we hear anything further.

Thanks

s 22(1)

l Senior Adviser

Constitutional Recognition Taskforce

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet | Indigenous Affairs

s 22(1)

s 22(1)

@pmc.gov.au | www.dpmc.gov.au | www.indigenous.gov.au

PO Box 6500 CANBERRA ACT 2600

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet acknowledges the traditional owners of country throughout Australia

and their continuing connection to land, sea and community. We pay our respect to them and their cultures, and to the

elders both past and present.

______________________________________________________________________

IMPORTANT: This message, and any attachments to it, contains information

that is confidential and may also be the subject of legal professional or

other privilege. If you are not the intended recipient of this message, you

must not review, copy, disseminate or disclose its contents to any other

party or take action in reliance of any material contained within it. If you

have received this message in error, please notify the sender immediately by

return email informing them of the mistake and delete all copies of the

message from your computer system.

______________________________________________________________________

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 22 of 211

Document 22 - Page 1 of 2

ATTACHMENT C

TALKING POINTS

• The Commonwealth Government remains committed to the recognition of

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the Constitution.

• The Referendum Council was appointed jointly by the Prime Minister and Leader

of the Opposition to conduct consultations and provide advice to Parliament on

the next steps towards a successful referendum, including timing of a referendum

and a possible model.

• The Uluru Statement was part of this process. That statement will now be

considered by the Referendum Council which wil report to the Parliament

through the Prime Minister and Leader of the Opposition.

s 22(1)

• We thank the delegates at Uluru for their work which wil now be considered by

the Referendum Council which wil in turn advise the Opposition Leader and

myself and through us the Parliament.

s 22(1)

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 23 of 211

Document 23 - Page 1 of 2

s 22(1)

From: s 22(1)

@pmc.gov.au]

Sent: Monday, 17 July 2017 5:48 PM

To: Virtue, Joanna; Lewis, David; s 22(1)

; 'Ian Nicholas';

s 22(1)

@aec.gov.au'; Johnston, Trish; Bulman, Ryan; O'Connor, Rachel; Taylor, Marie; Hill,

Leonard; Roddam, Mark; Curnow, Justine; Jocumsen, Katrina; Williams, Toni; Jacomb, Brendan;

Sloan, Troy; Curnow, Justine; s 22(1)

Cc: Anderson, Gayle; Harris, Sally; s 22(1)

Craigie, Michelle; s 22(1)

; Story,

William; Walker, John; Roberts, Anne-Marie; Conway, Rebekah; Keating, Kate; s 22(1)

Subject: Constitutional Recognition - whole of government talking points [DLM=For-Official-Use-

Only]

For Official Use Only

Good afternoon colleagues

This afternoon the Referendum Council’s Final Report was publically released. A copy is attached

to this email and can be found at https://www.referendumcouncil.org.au/final-report.

I also attach for your use a copy of our updated Whole of Government talking points.

If you require any further information, please let us know.

Kind regards

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 24 of 211

Document 23 - Page 2 of 2

s 22(1)

l A/g Assistant Secretary

Constitutional Recognition Taskforce

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet | Indigenous Affairs

s 22(1)

s 22(1)

@pmc.gov.au | www.dpmc.gov.au | www.indigenous.gov.au

PO Box 6500 CANBERRA ACT 2600

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet acknowledges the traditional owners of country throughout Australia

and their continuing connection to land, sea and community. We pay our respect to them and their cultures, and to the

elders both past and present.

______________________________________________________________________

IMPORTANT: This message, and any attachments to it, contains information

that is confidential and may also be the subject of legal professional or

other privilege. If you are not the intended recipient of this message, you

must not review, copy, disseminate or disclose its contents to any other

party or take action in reliance of any material contained within it. If you

have received this message in error, please notify the sender immediately by

return email informing them of the mistake and delete all copies of the

message from your computer system.

______________________________________________________________________

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 25 of 211

Document 24 - Page 1 of 9

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY

17 July 2017

Indigenous Constitutional Recognition

Whole-of-Government Talking Points

• The Government remains committed to the recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in

the Constitution.

• The Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition have now received the Final Report of the Referendum

Council. The Report is available on the Referendum Council’s website.

• The Referendum Council was jointly appointed by the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition to

conduct consultations and provide advice to the Parliament on the next steps towards a successful

referendum.

• The Referendum Council conducted a substantial Indigenous designed and led consultation process,

including 12 First Nations Regional Dialogues across the country and culminated in the National

Constitutional Convention where the ‘Uluru Statement from the Heart’ was adopted.

s 22(1)

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 26 of 211

Document 25 - Page 1 of 2

s 22(1)

From: s 22(1)

@pmc.gov.au]

Sent: Monday, 17 July 2017 5:48 PM

To: Virtue, Joanna; Lewis, David; s 22(1)

; 'Ian Nicholas';

s 22(1)

@aec.gov.au'; Johnston, Trish; Bulman, Ryan; O'Connor, Rachel; Taylor, Marie; Hill,

Leonard; Roddam, Mark; Curnow, Justine; Jocumsen, Katrina; Williams, Toni; Jacomb, Brendan;

Sloan, Troy; Curnow, Justine; s 22(1)

Cc: Anderson, Gayle; Harris, Sally; s 22(1)

Craigie, Michelle; s 22(1)

; Story,

William; Walker, John; Roberts, Anne-Marie; Conway, Rebekah; Keating, Kate; s 22(1)

Subject: Constitutional Recognition - whole of government talking points [DLM=For-Official-Use-

Only]

For Official Use Only

Good afternoon colleagues

This afternoon the Referendum Council’s Final Report was publically released. A copy is attached

to this email and can be found at https://www.referendumcouncil.org.au/final-report.

I also attach for your use a copy of our updated Whole of Government talking points.

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 27 of 211

Document 25 - Page 2 of 2

If you require any further information, please let us know.

Kind regards

s 22(1)

l A/g Assistant Secretary

Constitutional Recognition Taskforce

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet | Indigenous Affairs

s 22(1)

s 22(1)

@pmc.gov.au | www.dpmc.gov.au | www.indigenous.gov.au

PO Box 6500 CANBERRA ACT 2600

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet acknowledges the traditional owners of country throughout Australia

and their continuing connection to land, sea and community. We pay our respect to them and their cultures, and to the

elders both past and present.

______________________________________________________________________

IMPORTANT: This message, and any attachments to it, contains information

that is confidential and may also be the subject of legal professional or

other privilege. If you are not the intended recipient of this message, you

must not review, copy, disseminate or disclose its contents to any other

party or take action in reliance of any material contained within it. If you

have received this message in error, please notify the sender immediately by

return email informing them of the mistake and delete all copies of the

message from your computer system.

______________________________________________________________________

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 28 of 211

Document 26 - Page 1 of 183

Final Report

of the Referendum Council

30 June 2017

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 29 of 211

© Commonwealth of Australia 2017

ISBN 978-1-925362-56-5 (print)

ISBN 978-1-925362-57-2 (PDF)

ISBN 978-1-925362-58-9 (HTML)

Copyright in extracts from the Uluru Statement from the Heart reproduced in this report vests with the

Mutitjulu Community Aboriginal Corporation and are reproduced with its permission.

‘

Rom Watangu: The law of the land’ (Appendix D) is reproduced with the kind permission of

Schwartz Media and

The Monthly magazine.

Creative Commons licence

Except where otherwise noted, all material presented in this document is provided under a Creative Commons

Attribution–Non-Commercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au).

The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website (accessible using the

links provided) as is the full legal code for the CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 AU licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-

nd/3.0/au/legalcode).

This document should be attributed as

Final Report of the Referendum Council.

Disclaimer

The material contained in this document has been developed by the Referendum Council. The views and opinions

expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the views of or have the endorsement of the Commonwealth

Government or of any minister, or indicate the Commonwealth’s commitment to a particular course of action. In

addition, the members of the Referendum Council, the Commonwealth Government, and its employees, officers and

agents accept no responsibility for any loss or liability (including reasonable legal costs and expenses) incurred or

suffered where such loss or liability was caused by the infringement of intellectual property rights, including the moral

rights, of any third person, including as a result of the publishing of the submissions.

Inquiries

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of this document are welcome at:

Group Manager, Indigenous Employment and Recognition

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

PO Box 6500

Canberra ACT 2600

Email: xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx@xxx.xxx.xx

Telephone: 02 6271 5111

Cover: photo James Widders-Hunt, design by Kylie Smith

Uluru Statement from the Heart image (p. i): photo Simonne Randall

Publishing consultant: Wilton Hanford Hanover

Sources of quotations in the Uluru Statement from the Heart (facing page):

… a spiritual notion … of sovereignty: International Court of Justice in its Advisory Opinion on Western Sahara (62)

(1975) ICJ Rep, [85]–[86], quoted in

Mabo v Queensland [No 2] (1992) 175 CLR 1 [40].

… the torment of our powerlessness: WEH Stanner,

Durmugam: A Nangiomeri (1959).

…

a rightful place: Gough Whitlam, ‘It’s Time’ (speech delivered at the Blacktown Civic Centre, 13 November 1972).

…

the coming together after a struggle: Galarrwuy Yunupingu, ‘

Rom Watangu’,

The Monthly (July 2016), 18.

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 30 of 211

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 31 of 211

Final Report of the Referendum Council

LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL

The Hon Malcolm Turnbull MP

Prime Minister

Parliament House

CANBERRA ACT 2600

The Hon Bill Shorten MP

Leader of the Opposition

Parliament House

CANBERRA ACT 2600

30 June 2017

Dear Prime Minister and Leader of the Opposition

We are proud to present you with the Final Report of the Referendum Council. This report

has been prepared in accordance with the Referendum Council’s Terms of Reference.

Yours sincerely

Pat Anderson AO

Mark Leibler AC

Co-Chair, Referendum Council

Co-Chair, Referendum Council

ii

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 32 of 211

FOREWORD FROM THE CO-CHAIRS

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have long struggled for constitutional recognition. As far

back as Yorta Yorta elder William Cooper’s letter to King George VI (1937), the Yirrkala Bark Petitions

(1963), the Larrakia Petition (1972) and the Barunga Statement (1988), First Peoples have sought a

fair place in our country.

All Prime Ministers of the modern era were conscious of the original omission of First Peoples from our

constitutional arrangements. Prime Minister the Hon Gough Whitlam spoke of the need for Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander peoples to take “their rightful place in this nation”. Prime Minister the Rt

Hon Malcolm Fraser established a Senate inquiry whose report,

200 Years Later: Report by the Senate

Standing Committee on Constitutional and Legal Affairs on the Feasibility of a Compact or ‘Makarrata’

between the Commonwealth and Aboriginal People, was delivered after the 1983 election. Prime

Minister the Hon Bob Hawke sought to respond to the Barunga Statement with his commitment for

a treaty or compact at the bicentenary of 1988. In his Redfern Speech in 1991, Prime Minister the

Hon Paul Keating said,

How well we recognise the fact that, complex as our contemporary identity is, it cannot be

separated from Aboriginal Australia.

Prime Minister the Hon John Howard committed to a referendum on the eve of the 2007 federal

election, saying:

I believe we must find room in our national life to formally recognise the special status of

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders as the first peoples of our nation.

These promising intentions never came to pass. They nevertheless confirm constitutional recognition

is longstanding and unfinished business for the nation.

This history, from an Aboriginal perspective, is eloquently captured by Referendum Council member

Galarrwuy Yunupingu in his essay ‘

Rom Watangu’ at

Appendix D.

What Aboriginal people ask is that the modern world now makes the sacrifices necessary to

give us a real future. To relax its grip on us. To let us breathe, to let us be free of the determined

control exerted on us to make us like you. And you should take that a step further and recognise

us for who we are, and not who you want us to be. Let us be who we are – Aboriginal people

in a modern world – and be proud of us. Acknowledge that we have survived the worst that the

past had thrown at us, and we are here with our songs, our ceremonies, our land, our language

and our people – our full identity. What a gift this is that we can give you, if you choose to accept

us in a meaningful way.

In 2010 Prime Minister the Hon Julia Gillard established the Expert Panel on the Recognition of

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in the Constitution, co-chaired by Patrick Dodson and

Mark Leibler, which reported in 2012. Prime Minister the Hon Tony Abbott established a Joint Select

Committee on Constitutional Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, co-chaired

by Senator Ken Wyatt and Senator Nova Peris, which reported in June 2015. Prime Minister the

Hon Malcolm Turnbull and Opposition Leader the Hon Bill Shorten then established this Referendum

Council in December 2015.

iii

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 33 of 211

Final Report of the Referendum Council

This report builds on the work of the Expert Panel and the Joint Select Committee. It takes into account

the political and legal responses to the earlier reports, as well as the views of Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander peoples and the general public.

We were required to consult specifically with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples on their

views of meaningful recognition. The 12 First Nations Regional Dialogues, which culminated in the

National Constitutional Convention at Uluru in May 2017, empowered First Peoples from across the

country to form a consensus position on the form constitutional recognition should take.

This is the first time in Australia’s history that such a process has been undertaken. It is a significant

response to the historical exclusion of First Peoples from the original process that led to the adoption

of the Australian Constitution. The outcomes of the First Nations Regional Dialogues and the National

Constitutional Convention are articulated in the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

The findings of our broader community consultation supported the findings of the First Nations

Regional Dialogues. This strengthens our conviction that the Voice to the Parliament proposal and

an extra-constitutional Declaration of Recognition will be acceptable to Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander peoples and to the broader Australian community. We propose these reforms because they

conform to the weight of views of First Peoples expressed in the First Nations Regional Dialogues as

well as those of the wider community. With focussed political leadership and continued multiparty

support for meaningful recognition, the Voice to the Parliament proposal can succeed at a referendum.

The consensus view of the Referendum Council is that these recommendations for constitutional

and extra-constitutional recognition are modest, reasonable, unifying and capable of attracting the

necessary support of the Australian people. A statement by Amanda Vanstone is at

Appendix E.

Pat Anderson – Referendum Council Co-Chair

Mark Leibler – Referendum Council Co-Chair

iv

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 34 of 211

Contents

ULURU STATEMENT FROM THE HEART

i

LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL

ii

FOREWORD FROM THE CO-CHAIRS

iii

INTRODUCTION 1

Recommendations 2

1. THE WORK OF THE REFERENDUM COUNCIL

3

1.1 The Referendum Council

3

1.2 Building on past processes

4

1.3 National consultation and community engagement process

5

1.4 Selecting the options to consider

5

1.5 Discussion Paper

7

1.6 Other matters

7

2. FIRST NATIONS REGIONAL DIALOGUES AND NATIONAL CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION

9

2.1 First Nations Regional Dialogues

10

2.2 National Constitutional Convention

16

3. BROADER COMMUNITY CONSULTATION PROCESS

33

3.1 Digital platform

33

3.2 Submissions

34

3.3 Outcomes

35

4. FINDINGS

36

Constitutional issues

36

CONCLUSION 38

Modest and substantive

38

Reasonable 38

Unifying 38

Capable of attracting the necessary support

39

APPENDIX A: REFERENDUM COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP

42

APPENDIX B: TERMS OF REFERENCE

46

APPENDIX C: REFERENDUM COUNCIL COMMUNIQUES

48

APPENDIX D: ROM WATANGU – THE LAW OF THE LAND

53

APPENDIX E: QUALIFYING STATEMENT FROM AMANDA VANSTONE

65

APPENDIX F: EXECUTIVE SUMMARIES FROM PREVIOUS REPORTS

68

APPENDIX G: KIRRIBILLI STATEMENT

88

APPENDIX H: DISCUSSION PAPER

92

APPENDIX I: PROCESS FOR FIRST NATIONS REGIONAL DIALOGUES

109

APPENDIX J: COX INALL RIDGEWAY REPORT ON DIGITAL CONSULTATIONS

114

APPENDIX K: URBIS ANALYSIS OF SUBMISSIONS RECEIVED

137

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 35 of 211

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 36 of 211

INTRODUCTION

The Australian story began long before the arrival of the First Fleet on 26 January 1788. We Australians

all know this. We have always known this.

As the Uluru Statement from the Heart puts it: the

‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes that

were the first sovereign Nations of the Australian continent and its adjacent islands, possessed it

under our own laws and customs’ and

‘[t]his our ancestors did, according to the reckoning of our

culture, from the Creation, according to the common law from “time immemorial”, and according to

science more than 60,000 years ago.’

This is the first part of the story of Australia, which tells of the epic discovery of our country by our

most ancient tribes who crossed the northern land bridge from Papua New Guinea and southeast

Asia, establishing in this country one of the planet’s earliest civilisations. It is the longest continuous

surviving civilisation.

With every advance of science our understanding increases, but the shadow of this ancient past

– and its enduring presence – has never disappeared from our consciousness. Though the

Great

Australian Silence about this history persisted for much of the first 150 years of British colonisation,

we have always known the truth.

We have known this but we did not acknowledge it and make it part of our Australian story.

The second part of the Australian story is recognised by 26 January: the arrival of the First Fleet and the

establishment of the first colony in New South Wales. From the perspective of those who laid claim to

the eastern seaboard of Australia under the sovereignty of the British Crown, this was a settlement.

From the perspective of the First Nations this was an invasion. Their land and sovereignty was annexed

without consent and without treating with the country’s rightful owners.

The words ‘settlement’ and ‘invasion’ are highly charged for both sides of this historic encounter, but

there is no use denying these two perspectives. It is understandable why some Australians speak of

settlement, and why some speak of invasion. The maturation of Australia will be marked by our ability

to understand both perspectives.

There is no doubt the second story of Australia is replete with triumph and failure, pride and regret,

celebration and sorrow, greatness and shame. Like human history the world over. There is no doubt our

constitutional system, our system of government, the rule of law, and our public institutions inherited

from Britain are the heritage of the Australian people and enure for the benefit of all of us, including

the First Peoples.

The third part of our Australian story is written by generations of migrants from Europe, Asia, the

Middle East, the Pacific and the world over, who have come to make their home in this continent.

They have made Australia a multicultural triumph of diversity in unity.

We now have the opportunity to bring together these three parts of the story of Australia through two

measures, one involving constitutional amendment and the other involving an extra-constitutional

symbolic statement.

1

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 37 of 211

Final Report of the Referendum Council

Recommendations

The Council recommends:

1. That a referendum be held to provide in the Australian Constitution for a representative

body that gives Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander First Nations a Voice to the Commonwealth Parliament. One of the specific functions of such a body, to be set out in legislation outside the Constitution, should include the function of monitoring the use of the heads of power in section 51 (xxvi) and section 122. The body will recognise the status of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the first peoples of Australia.

It will be for the Parliament to consider what further definition is required before the proposal is in a

form appropriate to be put to a referendum. In that respect, the Council draws attention to the Guiding

Principles that emerged from the National Constitutional Convention at Uluru on 23–26 May 2017 and

advises that the support of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, in terms of both process and

outcome, will be necessary for the success of a referendum.

In consequence of the First Nations Regional Dialogues, the Council is of the view that the only option

for a referendum proposal that accords with the wishes of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

is that which has been described as providing, in the Constitution, for a Voice to Parliament.

In principle, the establishment by the Constitution of a body to be a Voice for First Peoples, with the

structure and functions of the body to be defined by Parliament, may be seen as an appropriate form of

recognition, of both substantive and symbolic value, of the unique place of Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander peoples in Australian history and in contemporary Australian society.

The Council recommends this option, understanding that finalising a proposal will involve further

consultation, including steps of the kind envisaged in the Guiding Principles adopted at the Uluru Convention.

The Council further recommends:

2. That an extra-constitutional Declaration of Recognition be enacted by legislation passed by

all Australian Parliaments, ideally on the same day, to articulate a symbolic statement of

recognition to unify Australians.

A Declaration of Recognition should be developed, containing inspiring and unifying words articulating

Australia’s shared history, heritage and aspirations. The Declaration should bring together the three parts

of our Australian story: our ancient First Peoples’ heritage and culture, our British institutions, and our

multicultural unity. It should be legislated by all Australian Parliaments, on the same day, either in the

lead up to or on the same day as the referendum establishing the First Peoples’ Voice to Parliament,

as an expression of national unity and reconciliation.

In addition, the Council reports that there are two matters of great importance to Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander peoples, as articulated in the Uluru Statement from the Heart, that can be

addressed outside the Constitution. The Uluru Statement called for the establishment of a Makarrata

Commission with the function of supervising agreement-making and facilitating a process of local and

regional truth telling. The Council recognises that this is a legislative initiative for Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander peoples to pursue with government. The Council is not in a position to make a specific

recommendation on this because it does not fall within our terms of reference. However, we draw

attention to this proposal and note that various state governments are engaged in agreement-making.

2

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 38 of 211

1. THE WORK OF THE REFERENDUM COUNCIL

1.1 The Referendum Council

The Referendum Council was appointed by the Prime Minister, the Hon Malcolm Turnbull MP, and

the Leader of the Opposition, the Hon Bill Shorten MP, on 7 December 2015. It comprises Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander members and non-Indigenous members from a range of expert fields and

backgrounds. At the time of drafting this report, Council Co-Chairs Pat Anderson AO and Mark Leibler

AC are joined by Professor Megan Davis, Andrew Demetriou, Murray Gleeson AC, Tanya Hosch, Kristina

Keneally, Jane McAloon, Noel Pearson, Michael Rose AM, Natasha Stott Despoja AM, Amanda Vanstone,

Dalassa Yorkston and Galarrwuy Yunupingu AM (represented by Denise Bowden). Details of current and

past members are at

Appendix A.

The Council’s terms of reference are at

Appendix B. They require us to:

1. Lead the process for national consultations and community engagement about constitutional

recognition, including a concurrent series of Indigenous designed and led consultations.

2. Be informed by the Parliamentary Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition of

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples chaired by Mr Ken Wyatt AM MP, with Deputy Chair,

Senator Nova Peris OAM. The Committee will have input into the discussion paper on various

issues regarding constitutional change to help facilitate an informed community discussion.

3. Consider the recommendations of the 2012 Expert Panel on Constitutional Recognition of

Indigenous Australians.

4. Report to the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition on:

– outcomes of national consultations and community engagement about constitutional

recognition, including Indigenous designed and led consultations;

– options for a referendum proposal, steps for finalising a proposal, and possible timing for a

referendum; and

– constitutional issues.

The Council first met on 14 December 2015 with the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition

in attendance. The Council met on 11 subsequent occasions.

3

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 39 of 211

Final Report of the Referendum Council

Meeting

Date

Location

1

14 December 2015

Sydney

2

28 January 2016

Melbourne

3

21 and 22 March 2016

Melbourne

4

10 May 2016

Melbourne

5

9 August 2016

Melbourne

6

20 October 2016

Melbourne

7

25 November 2016

Canberra

8

6 December 2016

Videoconference

9

20 March 2017

Melbourne

10

17 May 2017

Videoconference

11

6 June 2017

Melbourne

12

27 June 2017

Melbourne

The Council released a communiqué following some of the meetings. These communiqués are at

Appendix D.

1.2 Building on past processes

Consistent with points 2 and 3 of our terms of reference, the Council was mindful of the need to pay

close regard to the work completed through previous processes and this largely accounted for the

structure of our Discussion Paper in

Appendix H. These processes include: the Parliamentary Joint

Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples 2015

(‘the Joint Select Committee’), the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Act of Recognition

Review Panel 2014 (‘the Act of Recognition Review Panel’) and the Expert Panel on Constitutional

Recognition of Indigenous Australians 2012 (‘the Expert Panel’). The options proposed by the Expert

Panel and the Joint Select Committee were the basis of the Council’s work and the subject of the

First Nations Regional Dialogues. The executive summaries and recommendations from these three

reports are at

Appendix F.

The Council’s establishment followed a meeting between the former Prime Minister, the Hon Tony

Abbott MP, the Leader of the Opposition, the Hon Bill Shorten MP, and 40 Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander leaders from around the country on 6 July 2015 at Kirribilli.

The Kirribilli meeting agreed on a number of outcomes. These included an agreement to hold a series

of community conferences across the country to provide an opportunity for everyone to have a say and

for all significant points of view to be considered. It was also agreed that a Referendum Council would

be established to progress a range of issues around constitutional change and inform the further steps

to be taken.

4

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 40 of 211

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders present at that meeting were united in their view that

any constitutional change must be substantive. The leaders stated the following:

[A]ny reform must involve substantive changes to the Australian Constitution. It must lay the

foundation for the fair treatment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples into the future.

A minimalist approach, that provides preambular recognition, removes section 25 and moderates

the race power [section 51(xxvi)], does not go far enough and would not be acceptable to

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The Kirribilli leaders recommended that there be an ongoing dialogue between Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander peoples and the Government to negotiate the proposal to be put to referendum, as well

as engagement about the acceptability of the proposed question. These recommendations were a key

motivation for the creation of this Council. The Kirribilli Statement is at

Appendix G.

1.3 National consultation and community engagement process

Point 1 of the Council’s terms of reference emphasises the importance of an Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander designed and led consultation process. The Council agreed early on in its work that this

process must not be a ‘tick a box’ exercise but a true dialogue between Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander peoples. It is the Council’s view that there is no practical purpose to suggesting changes to the

Constitution unless they are what Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples want.

The First Nations Regional Dialogues were therefore at the heart of the Referendum Council’s work.

The methodology and outcomes of this process are detailed in

Chapter 2.

The Council’s terms of reference also required it to engage with the broader community and encourage

understanding of the need for constitutional reform. We understood this as necessary not only for a

successful referendum, but for a productive consultation process. The broader community, including

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who did not attend the regional dialogues, were

encouraged to share their views through our digital platform, written submissions process and targeted

stakeholder engagement.

Further detail on these processes, and their outcomes, is in

Chapter 3.

1.4 Selecting the options to consider

The Council adopted the Expert Panel’s four principles to guide its assessment of proposals for

constitutional reform, meaning that each proposal must:

• contribute to a more unified and reconciled nation;

• be of benefit to and accord with the wishes of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples;

• be capable of being supported by an overwhelming majority of Australians from across the political

and social spectrums; and

• be technically and legally sound.

5

Attorney-General's Department documents released under FOI23/417 - Date of access: 11/09/2024

Page 41 of 211

Final Report of the Referendum Council

Five proposals for reform formed the basis of the Council’s work. Four of these proposals are

based on the substantial overlap between the Expert Panel’s recommended model, and the

Joint Select Committee:

• a statement acknowledging Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Australians

(which could be placed in the Constitution or outside it);

• amending the existing ‘race power’, section 51(xxvi) of the Constitution, or deleting it and inserting

a new power for the Commonwealth to make laws for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples;

• inserting a guarantee against racial discrimination, Section 116A, into the Constitution; and

• deleting section 25, which contemplates the possibility of a state government excluding some

Australians from voting on the basis of their race.

The Council also included a fifth option, providing for a First Peoples’ Voice to be heard by

Parliament, and the right to be consulted on legislation and policies that relate to Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander peoples. This proposal emerged after the Expert Panel’s work had concluded,

as a response to the political blockages for the Expert Panel’s proposed section 116A, a constitutional

non-discrimination clause. Submissions supporting a proposal for the Voice were provided to the

Joint Select Committee.1, As a result, the Committee noted that the proposal ‘would benefit from

wider community and debate’ and suggested:

community consultation, particularly with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples … in order

to gauge community views on the establishment of such a body, and [so] that Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander peoples may consider [if] it has merit and [if they] may wish to pursue it in

the future.’2

The Council wrote to the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition on 22 March 2016 proposing

these five options as the basis of our consultations. On 7 April 2016, the Council received their approval

to proceed in this regard.

The Council was also conscious of concrete actions toward negotiating treaties commencing in

Victoria and in South Australia during the its tenure, and the Northern Territory Government has also

committed to commence discussions during this time. These treaty negotiations have had a significant

impact on our engagement process.

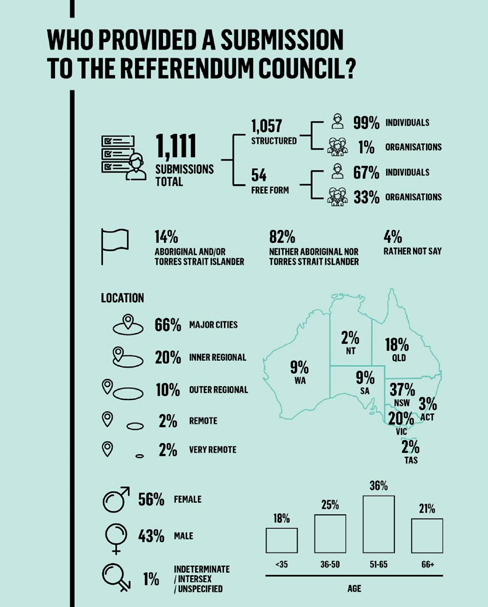

The Council adopted the view that, although the five proposed options formed an important and useful